Photo of the Day

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

They look amazingly similar to the green leaves on a deciduous tree. During the late summer and autumn, they spend their time as adults in the cover of the forest canopy. They prefer to run and hop rather than fly. But despite their discretion, you’re not likely to miss the Common True Katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia).

Take a listen and you may hear the male’s nocturnal calls filling the treetops of woodlands and shady neighborhoods throughout the lower Susquehanna valley right now. The loud, raspy “ka-ty-did, she-did, she-didn’t” is reliably answered by other nearby males as competition for willing females reaches a frenzy. In mature forests where populations are dense, this rowdy chorus can reach a remarkable volume.

The Common True Katydid’s song is like a soundtrack for the oft times melancholy mood of autumn. As the days shorten and a chill fills the air, the rate of the Common True Katydid’s call becomes slower and its tone deeper in response to the falling temperatures. Males continue forcing a sluggish call until freezing conditions finally bring about their demise. Another generation and another season gone.

Grasshoppers are perhaps best known for the occasions throughout history when an enormous congregation of these insects—a “plague of locusts”—would assemble and rove a region to feed. These swarms, which sometimes covered tens of thousands of square miles or more, often decimated crops, darkened the sky, and, on occasion, resulted in catastrophic famine among human settlements in various parts of the world.

The largest “plague of locusts” in the United States occurred during the mid-1870s in the Great Plains. The Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus), a grasshopper of prairies in the American west, had a range that extended east into New England, possibly settling there on lands cleared for farming. Rocky Mountain Locusts, aside from their native habitat on grasslands, apparently thrived on fields planted with warm-season crops. Like most grasshoppers, they fed and developed most vigorously during periods of dry, hot weather. With plenty of vegetative matter to consume during periods of scorching temperatures, the stage was set for populations of these insects to explode in agricultural areas, then take wing in search of more forage. Plagues struck parts of northern New England as early as the mid-1700s and were numerous in various states in the Great Plains through the middle of the 1800s. The big ones hit between 1873 and 1877 when swarms numbering as many as trillions of grasshoppers did $200 million in crop damage and caused a famine so severe that many farmers abandoned the westward migration. To prevent recurrent outbreaks of locust plagues and famine, experts suggested planting more cool-season grains like winter wheat, a crop which could mature and be harvested before the grasshoppers had a chance to cause any significant damage. In the years that followed, and as prairies gave way to the expansive agricultural lands that presently cover most of the Rocky Mountain Locust’s former range, the grasshopper began to disappear. By the early years of the twentieth century, the species was extinct. No one was quite certain why, and the precise cause is still a topic of debate to this day. Conversion of nearly all of its native habitat to cropland and grazing acreage seems to be the most likely culprit.

In the Mid-Atlantic States, the mosaic of the landscape—farmland interspersed with a mix of forest and disturbed urban/suburban lots—prevents grasshoppers from reaching the densities from which swarms arise. In the years since the implementation of “Green Revolution” farming practices, numbers of grasshoppers in our region have declined. Systemic insecticides including neonicotinoids keep grasshoppers and other insects from munching on warm-season crops like corn and soybeans. And herbicides including 2,4-D (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) have, in effect, become the equivalent of insecticides, eliminating broadleaf food plants from the pasturelands and hayfields where grasshoppers once fed and reproduced in abundance. As a result, few of the approximately three dozen species of grasshoppers with ranges that include the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are common here. Those that still thrive are largely adapted to roadsides, waste ground, and small clearings where native and some non-native plants make up their diet.

Here’s a look at four species of grasshoppers you’re likely to find in disturbed habitats throughout our region. Each remains common in relatively pesticide-free spaces with stands of dense grasses and broadleaf plants nearby.

CAROLINA GRASSHOPPER

Dissosteira carolina

DIFFERENTIAL GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus differentialis

TWO-STRIPED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus bivittatus

RED-LEGGED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus femurrubrum

Protein-rich grasshoppers are an important late-summer, early-fall food source for birds. The absence of these insects has forced many species of breeding birds to abandon farmland or, in some cases, disappear altogether.

During the past two weeks, over 150 American Flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) have been reported in the eastern half of the United States, well north of their usual range—northern South America; Cuba, the Bahamas, and other Caribbean Islands; and the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. They are also found on the Galapagos Islands. Prior to being extirpated by hunting during the early years of the twentieth century, American Flamingos nested in the Everglades of Florida as well.

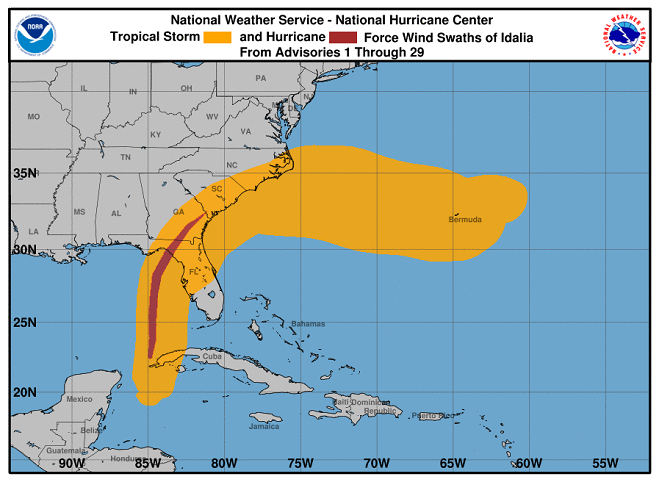

The recent influx of these tropical vagrants into the eastern states is attributed to Hurricane Idalia, a storm that formed in the midst of flamingo territory during the final week of August. Idalia got its start over tropical waters off Yucatan before progressing north through the Gulf of Mexico off Cuba to make landfall in the “Big Bend” area of Florida.

Birds of warm water seas regularly become entangled within tropical storms and hurricanes. In most cases, it’s oceanic seabirds including petrels, shearwaters, terns, and gulls that seek refuge from turbulent conditions by remaining inside the storm’s eye or within the margins of the rotating bands. The duration of the experience and the fitness of each individual bird may determine just how many survive such an ordeal. As a storm makes landfall, the survivors put down on inland bodies of water, often in unexpected places hundreds of miles from the nearest coastline. Some may linger in these far-flung areas to feed and gain strength before finding their way down rivers back to sea.

For birds like American Flamingos, which don’t spend a large portion of their lives on the wing over vast oceanic waters, becoming entangled in a tropical weather system can easily be a life-ending event. American Flamingos, despite their size and lanky appearance, are quite agile fliers. When necessary, some populations travel significant distances in search of new food sources. Some closely related migratory species of flamingos have been recorded at altitudes exceeding 10,000 feet. But becoming trapped in a hurricane for an extended period of time could easily erode the endurance of even the strongest of fliers. And once out over open water, there’s nowhere for a flamingo to come down for a rest.

It appears probable that, during the final week of August, hundreds of American Flamingos did find themselves drawn away from their familiar tidal flats and salty lagoons to be swept into the spinning clouds and gusty downpours of Hurricane Idalia as it churned off the Yucatan coast. Despite the dangers, more than 150 of them completed a journey within its clutches to cross the Gulf of Mexico and land in the Eastern United States.

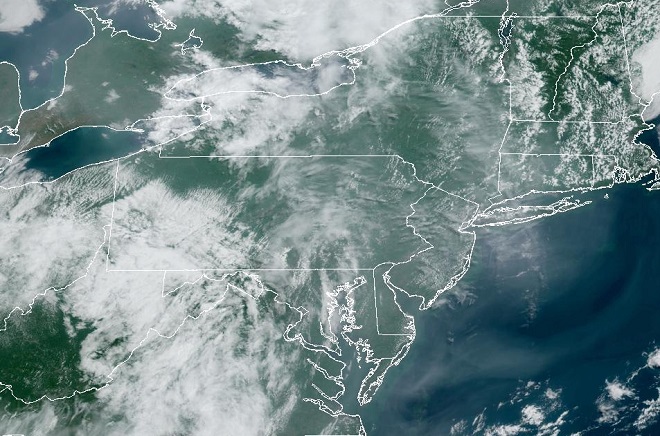

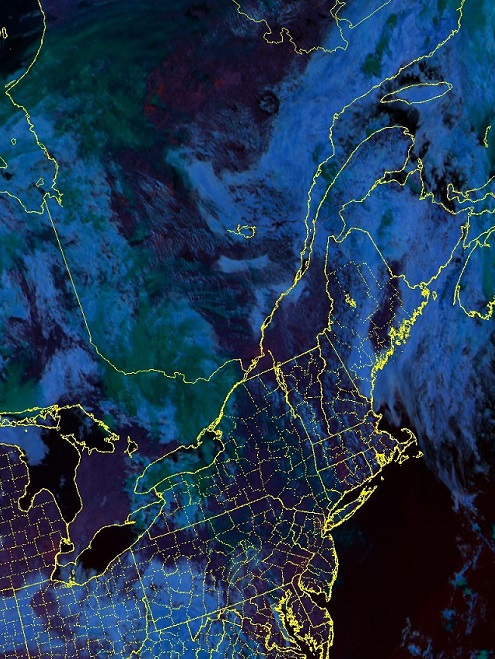

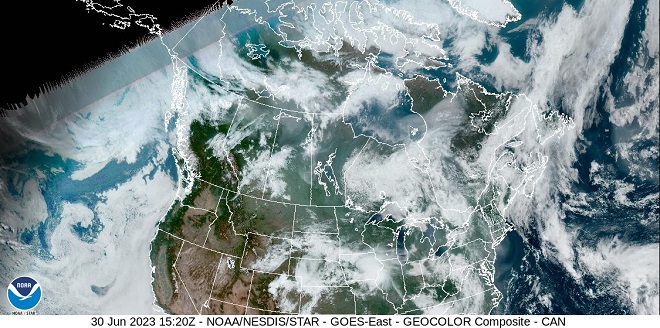

Amy Davis in a report for the American Birding Association compiled a list of American Flamingo sightings from the days following the landfall of Hurricane Idalia. We’ve plotted those sightings on a satellite image of the storm.

The majority of the flamingos that survived this harrowing trip found a place to put down along the coast. But as the reader will notice, a significant number of the sightings were outside the path of the storm in areas not reached by even the outermost bands of clouds. Flamingos in Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky/Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania were found at inland bodies of water, most on the days immediately following the storm’s landfall. The lone exception, the Pennsylvania birds, were discovered a week after landfall (but may have been there days longer). How and why did these birds find their way so far inland at places so distant from the storm…and home? And how did they get there so quickly? The counterclockwise rotation of the hurricane wouldn’t slingshot them in that direction, would it?

Let’s have a look at the surface map showing us the weather in the states outside the direct influence of Hurricane Idalia during the storm’s landfall on August 30, 2023…

Now check out this satellite view of the storm during the hours following landfall…

Click the image above to play a GIF animation of GOES-16 satellite photos showing Idalia after landfall and the strong “flamingo highway” winds between the fronts. (It’s a big file, so give it a little time to load.) You’ll also note the ferocious lightning associated with both Huricane Idalia and Hurricane Franklin.

Did the inland flamingos catch a ride on these stiff “flamingo highway” winds? If not, they may have had a little help from a high pressure ridge that became established over the southern Appalachians as Idalia crept out to sea. The clockwise rotation of this ridge kept a similar flow over the “flamingo highway” for much of the four days that followed.

For vagrant birds including those carried away to distant lands by hurricanes and other storms, the challenges of finding food and avoiding hazards including disease, unfamiliar predators, and extreme weather can be a matter of life and death. For American Flamingos now loafing and feeding in the Eastern United States outside Florida, the hardest part of their journey is yet to come. They need to find their way back south to suitable tropical habitat before cold weather sets in. The perils are many. Theirs is not an enviable predicament.

To pass the afternoon, we sat quietly along the edge of a pond created recently by North American Beavers (Castor canadensis). They first constructed their dam on this small stream about five years ago. Since then, a flourishing wetland has become established. Have a look.

Isn’t that amazing? North American Beavers build and maintain what human engineers struggle to master—dams and ponds that reduce pollution, allow fish passage, and support self-sustaining ecosystems. Want to clean up the streams and floodplains of your local watershed? Let the beavers do the job!

“Waves” of warblers and other Neotropical songbirds continue to roll along the ridgetops of southern Pennsylvania. The majority of these migrants are headed to wintering habitat in the tropics after departing breeding grounds in the forests of southern Canada. At Second Mountain Hawk Watch, today’s early morning flight kicked off at sunrise, then slowed considerably by 8:30 A.M. E.D.T. Once again, in excess of 400 warblers were found moving through the trees and working their way southwest along the spine of the ridge. Each of the 12 species seen yesterday were observed today as well. In addition, there was a Northern Parula and a Canada Warbler. Today’s flight was dominated by Bay-breasted, Blackburnian, Black-throated Green, and Tennessee Warblers.

Other interesting Neotropical migrants joined the “waves” of warblers…

During the recent couple of mornings, a tide of Neotropical migrants has been rolling along the crests of the Appalachian ridges and Piedmont highlands of southern Pennsylvania. In the first hours of daylight, “waves” of warblers, vireos, flycatchers, tanagers, and other birds are being observed flitting among the sun-drenched foliage as they feed in trees along the edges of ridgetop clearings. Big fallouts have been reported along Kittattiny Ridge/Blue Mountain at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and at Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch. Birds are also being seen in the Furnace Hills of the Piedmont.

Here are some of the 300 to 400 warblers (a very conservative estimate) seen in a “wave” found working its way southwest through the forest clearing at the Second Mountain Hawk Watch in Lebanon County this morning. The feeding frenzy endured for two hours between 7 and 9 A.M. E.D.T.

Not photographed but observed in the mix of species were several Black-throated Blue Warblers and American Redstarts.

In addition to the warblers, other Neotropical migrants were on the move including two Common Nighthawks, a Broad-winged Hawk, a Least Flycatcher (Empidonax minimus), and…

Then, there was a taste of things to come…

Seeing a “wave” flight is a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Visiting known locations for observing warbler fallouts such as hawk watches, ridgetop clearings, and peninsular shorelines can improve your chances of witnessing one of these memorable spectacles by overcoming the first variable. To overcome the second, be sure to visit early and often. See you on the lookout!

As we enter September, autumn bird migration is well underway. Neotropical species including warblers, vireos, flycatchers, and nighthawks are already headed south. Meanwhile, the raptor migration is ramping up and hawk watch sites throughout the Mid-Atlantic States are now staffed and counting birds. In addition to the expected migrants, there have already been sightings of some unusual post-breeding wanderers. Yesterday, a Wood Stork (Mycteria americana) was seen passing Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and a Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus) that spent much of August in Juniata County was seen from Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch while it was hunting in a Perry County field six miles to the north of the lookout! Both of these rarities are vagrants from down Florida way.

To plan a visit to a hawk watch near you, click on the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page to find a list and brief description of suggested sites throughout the Mid-Atlantic region. “Hawkwatcher’s Helper” also includes an extensive photo guide for identifying the raptors you’re likely to see.

And to identify those confusing fall warblers and other migrants, click the “Birds” tab at the top of this page and check out the photo guide contained therein. It includes nearly all of the species you’re likely to see in the lower Susquehanna valley.

At Lake Redman just to the south of York, Pennsylvania, a draw down to provide drinking water to the city while maintenance is being performed on the dam at neighboring Lake Williams, York’s primary water source, has fortuitously coincided with autumn shorebird migration. Here’s a sample of the numerous sandpipers and plovers seen today on the mudflats that have been exposed at the southeast end of the lake…

Not photographed but present at Lake Redman were at least two additional species of shorebirds, Killdeer and Spotted Sandpiper—bringing the day’s tally to ten. Not bad for an inland location! It’s clearly evident that these waders overfly the lower Susquehanna valley in great numbers during migration and are in urgent need of undisturbed habitat for making stopovers to feed and rest so that they might improve their chances of surviving the long journey ahead of them. Mud is indeed a much needed refuge.

It may be one of the most treasured plants among native landscape gardeners. The Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis) blooms in August each year with a startling blaze of red color that, believe it or not, will sometimes be overlooked in the wild.

The Cardinal Flower grows in wetlands as well as in a variety of moist soils along streams, rivers, lakes, and ponds. Shady locations with short periods of bright sun each day seem to be favored for an abundance of color.

The Cardinal Flower can be an ideal plant for attracting hummingbirds, bees, butterflies, and other late-summer pollinators. It grows well in damp ground, especially in rain gardens and along the edges streams, garden ponds, and stormwater retention pools. If you’re looking to add Cardinal Flower to your landscape, you need first to…

Cardinal Flower plants are available at many nurseries that carry native species of garden and/or pond plants. Numerous online suppliers offer seed for growing your own Cardinal Flowers. Some sell potted plants as well. A new option is to grow Cardinal Flowers from tissue cultures. Tissue-cultured plants are raised in laboratory media, so the pitfalls of disease and hitchhikers like invasive insects and snails are eliminated. These plants are available through the aquarium trade from most chain pet stores. Though meant to be planted as submerged aquatics in fish tank substrate, we’ve reared the tissue-cultured stock indoors as emergent plants in sandy soil and shallow water through the winter and early spring. When it warms up, we transplant them into the edges of the outdoor ponds to naturalize. As a habit, we always grow some Cardinal Flower plants in the fish tanks to take up the nitrates in the water and to provide a continuous supply of cuttings for starting more emergent stock for outdoor use.

Looking for a native wildflower that’s tall, showy, and a great choice for attracting wildlife, especially butterflies and bees? Then check out Wild Senna (Senna hebecarpa).

Wild Senna, also known as American Senna, is a host plant for the larvae of Cloudless Sulphur and Sleepy Orange (Eurema nicippe) butterflies. It thrives in almost any moist, well-drained soil in habitats including open woodlands, forest edges, meadows, and gardens like yours. Its height at flowering ranges from three to six feet. If you prefer, this perennial wildflower can even be cultivated as a shrub-like form. It is easily grown from seed, which is available from Ernst Conservation Seeds of Meadville, Pennsylvania, as well as numerous other vendors. And don’t forget to give Wild Senna’s two close relatives, Partridge Pea and Maryland Senna, a try as well. They attract the same species of butterflies and are just as easy to grow. You’ll like ’em.

Your best bet for finding migrating shorebirds in the lower Susquehanna region is certainly a visit to a sandbar or mudflat in the river. The Conejohela Flats off Washington Boro just south of Columbia is a renowned location. Some man-made lakes including the one at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area are purposely drawn down during the weeks of fall migration to provide exposed mud and silt for feeding and resting sandpipers and plovers. But with the Susquehanna running high due to recent rains and the cost of fuel trending high as well, maybe you want to stay closer to home to do your observing.

Fortunately for us, migratory shorebirds will drop in on almost any biologically active pool of shallow water and mud that they happen to find. This includes flooded portions of fields, construction sites, and especially stormwater retention basins. We stopped by a new basin just west of Hershey, Pennsylvania, and found more than two dozen shorebirds feeding and loafing there. We took each of these photographs from the sidewalk paralleling the south shore of the pool, thus never flushing or disturbing a single bird.

So don’t just drive by those big puddles, stop and have a look. You never know what you might find.

We’ve got the summertime blues for you, right here at susquehannawildlife.net…

…so don’t let the summertime blues get you down. Grab a pair of binoculars and/or a camera and go for a stroll!

If you’re feeling the need to see summertime butterflies and their numbers just don’t seem to be what they used to be in your garden, then plan an afternoon visit to the Boyd Big Tree Preserve along Fishing Creek Valley Road (PA 443) just east of U.S. 22/322 and the Susquehanna River north of Harrisburg. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources manages the park’s 1,025 acres mostly as forested land with more than ten miles of trails. While located predominately on the north slope of Blue Mountain, a portion of the preserve straddles the crest of the ridge to include the upper reaches of the southern exposure.

Fortunately, one need not take a strenuous hike up Blue Mountain to observe butterflies. Open space along the park’s quarter-mile-long entrance road is maintained as a rolling meadow of wildflowers and cool-season grasses that provide nectar for adult butterflies and host plants for their larvae.

Do yourself a favor and take a trip to the Boyd Big Tree Preserve Conservation Area. Who knows? It might actually inspire you to convert that lawn or other mowed space into much-needed butterfly/pollinator habitat.

While you’re out, you can identify your sightings using our photographic guide—Butterflies of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed—by clicking the “Butterflies” tab at the top this page. And while you’re at it, you can brush up on your hawk identification skills ahead of the upcoming migration by clicking the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab. Therein you’ll find a listing and descriptions of hawk watch locations in and around the lower Susquehanna region. Plan to visit one or more this autumn!

Those mid-summer post-breeding wanders continue to delight birders throughout the Mid-Atlantic States. One colorful denizen of ponds and wetlands that has yet to put in an appearance in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed this year is the Black-bellied Whistling Duck. You might remember this species from earlier posts describing the fortieth anniversary of your editor’s journey to the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Like many other birds, the Black-bellied Whistling Duck has been extending its range north from Texas, Florida, and other states along the Gulf Coastal Plain. Populations of these waterfowl are chiefly resident birds with some short-distance movement to find suitable habitat for feeding and nesting. They are not usually migratory, so summertime wandering may be the mechanism for their discovery of new habitats advantageous for nesting in areas north of their current home.

Presently, at least two dozen Black-bellied Whistling Ducks are being seen regularly at a stormwater retention pond in a housing subdivision along Amalfi Drive west of Smyrna, Delaware. This small population of avian tourists has spent at least two summers in the area. Just yesterday, Black-bellied Whistling Ducks were seen and photographed about ten miles to the east at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Nine were counted there while 27 were being watched simultaneously at the Amalfi site. Earlier this week, a single Black-bellied Whistling Duck visited the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge in Philadelphia, indicating that the influx of these vagrants has transited the entire Delmarva Peninsula and entered Pennsylvania. So while you’re out watching for those first southbound migrants of the year, be on the lookout for wayward wanderers too—wanderers like Black-bellied Whistling Ducks!

At just after 8:30 this evening, an Antares rocket carrying a Cygnus supply capsule launched from the NASA flight facility on Delmarva Peninsula at Wallops Island, Virginia. We took a walk on the Veterans Memorial Bridge over the Susquehanna at Columbia-Wrightsville to have a look at the spacecraft as it powered its way into orbit for a rendezvous with the International Space Station.

Unfortunately, a smoky haze from wildfires still burning in Canada obscured our view of the ascending rocket as it cleared our horizon and made its way downrange across the Atlantic.

But on the brighter side, we were spared any significant disappointment. It just so happened that the Antares/Cygnus rocket wasn’t the only launch visible from the Veteran’s Memorial Bridge this evening…

Here in a series of photographs are just a handful of the reasons why the land stewards at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area and other properties where conservation and propagation practices are employed delay the mowing of fields composed of cool-season grasses until after August 15 each year.

Right now is a good time to visit Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area to see the effectiveness a delayed mowing schedule can have when applied to fields of cool-season grasses. If you slowly drive, walk, or bicycle the auto tour route on the north side of the lake, you’ll pass through vast areas maintained as cool-season and warm-season grasses and early successional growth—and you’ll have a chance to see these and other grassland birds raising their young. It’s like a trip back in time to see farmlands they way they were during the middle years of the twentieth century.

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

Visitors stopping by Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area this week found yet another post-breeding wanderer feeding in the shallows of the main lake and adjacent pond along Hopeland Road—a juvenile Little Blue Heron.

The juvenile Little Blue Heron is a white bird resembling an egret during its first year. At about one year of age, it begins molt into a deep blue adult plumage. Young birds are notorious for roaming inland and north from breeding areas along the Atlantic coast and throughout the south. They are a post-breeding wanderer nowhere near as rare as the Limpkin seen at Middle Creek a week ago; a few are found each summer in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

As oft times happens, birders attracted to see one unusual bird find another in the vicinity. So with fall shorebird migration ramping up, the discovery of something out of the ordinary isn’t a total surprise, particularly where habitat is good and people are watching.

The arrival of a Hudsonian Godwit is not an unheard of occurrence in the lower Susquehanna region, but locating one that sticks around and provides abundant viewing opportunities is a rarity. This adult presumably left the species’ breeding areas in Alaska or central/western Canada in recent weeks to begin its southbound movement. Hudsonian Godwits pass through the eastern United States only during the autumn migration, and the majority fly by without being noticed along a route that mostly takes them offshore of the Mid-Atlantic States.

Mid-summer can be a less than exciting time for those who like to observe wild birds. The songs of spring gradually grow silent as young birds leave the nest and preoccupy their parents with the chore of gathering enough food to satisfy their ballooning appetites. To avoid predators, roving families of many species remain hidden and as inconspicuous as possible while the young birds learn how to find food and handle the dangers of the world.

But all is not lost. There are two opportunities for seeing unique birds during the hot and humid days of July.

First, many shorebirds such as sandpipers, plovers, dowitchers, and godwits begin moving south from breeding grounds in Canada. That’s right, fall migration starts during the first days of summer, right where spring migration left off. The earliest arrivals are primarily birds that for one reason on another (age, weather, food availability) did not nest this year. These individuals will be followed by birds that completed their breeding cycles early or experienced nest failures. Finally, adults and juveniles from successful nests are on their way to the wintering grounds, extending the movement into the months we more traditionally start to associate with fall migration—late August into October.

For those of you who find identifying shorebirds more of a labor than a pleasure, I get it. For you, July can bring a special treat—post-breeding wanderers. Post-breeding wanderers are birds we find roaming in directions other than south during the summer months, after the nesting cycle is complete. This behavior is known as “post-breeding dispersal”. Even though we often have no way of telling for sure that a wandering bird did indeed begin its roving journey after either being a parent or a fledgling during the preceding nesting season, the term post-breeding wanderer still applies. It’s a title based more on a bird sighting and it’s time and place than upon the life cycle of the bird(s) being observed. Post-breeding wanderers are often southern species that show up hundreds of miles outside there usual range, sometimes traveling in groups and lingering in an adopted area until the cooler weather of fall finally prompts them to go back home. Many are birds associated with aquatic habitats such as shores, marshes, and rivers, so water levels and their impact on the birds’ food supplies within their home range may be the motivation for some of these movements. What makes post-breeding wanderers a favorite among many birders is their pop. They are often some of our largest, most colorful, or most sought-after species. Birds such as herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, stilts, avocets, terns, and raptors are showy and attract a crowd.

While it’s often impossible to predict exactly which species, if any, will disperse from their typical breeding range in a significant way during a given year, some seem to roam with regularity. Perhaps the most consistent and certainly the earliest post-breeding wanderer to visit our region is the “Florida Bald Eagle”. Bald Eagles nest in “The Sunshine State” beginning in the fall, so by early spring, many of their young are on their own. By mid-spring, many of these eagles begin cruising north, some passing into the lower Susquehanna valley and beyond. Gatherings of dozens of adult Bald Eagles at Conowingo Dam during April and May, while our local adults are nesting and after the wintering birds have gone north, probably include numerous post-breeding wanderers from Florida and other Gulf Coast States.

So this week, what exactly was it that prompted hundreds of birders to travel to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area from all over the Mid-Atlantic States and from as far away as Colorado?

Was it the majestic Great Blue Herons and playful Killdeer?

Was it the colorful Green Herons?

Was it the Great Egrets snapping small fish from the shallows?

Was it the small flocks of shorebirds like these Least Sandpipers beginning to trickle south from Canada?

All very nice, but not the inspiration for traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles to see a bird.

It was the appearance of this very rare post-breeding wanderer…

…Pennsylvania’s first record of a Limpkin, a tropical wading bird native to Florida, the Caribbean Islands, and South America. Many observers visiting Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area had never seen one before, so if they happen to be a “lister”, a birder who keeps a tally of the wild bird species they’ve seen, this Limpkin was a “lifer”.

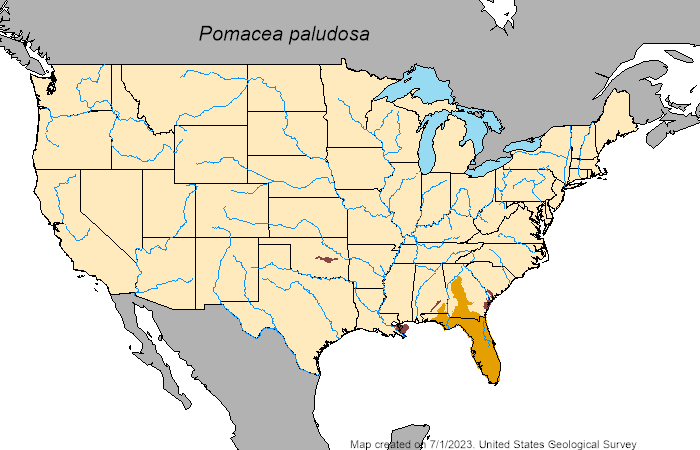

The Limpkin is an inhabitant of vegetated marshlands where it feeds almost exclusively upon large snails of the family Ampullariidae, including the Florida Applesnail (Pomacea paludosa), the largest native freshwater snail in the United States.

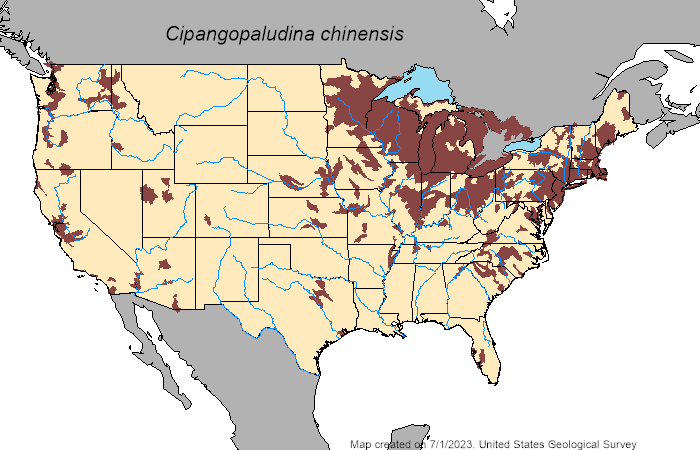

Observations of the Limpkin lingering at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area have revealed a pair of interesting facts. First, in the absence of Florida Applesnails, this particular Limpkin has found a substitute food source, the non-native Chinese Mystery Snail (Cipangopaludina chinensis). And second, Chinese Mystery Snails have recently become established in the lakes, pools, and ponds at the refuge, very likely arriving as stowaways on Spatterdock (Nuphar advena) and/or American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea), native transplants brought in during recent years to improve wetland habitat and process the abundance of nutrients (including waterfowl waste) in the water.

The Middle Creek Limpkin’s affinity for Chinese Mystery Snails may help explain how it was able to find its way to Pennsylvania in apparent good health. Look again at the map showing the range of the Limpkin’s primary native food source, the Florida Applesnail. Note that there are established populations (shown in brown) where these snails were introduced along the northern coast of Georgia and southern coast of South Carolina…

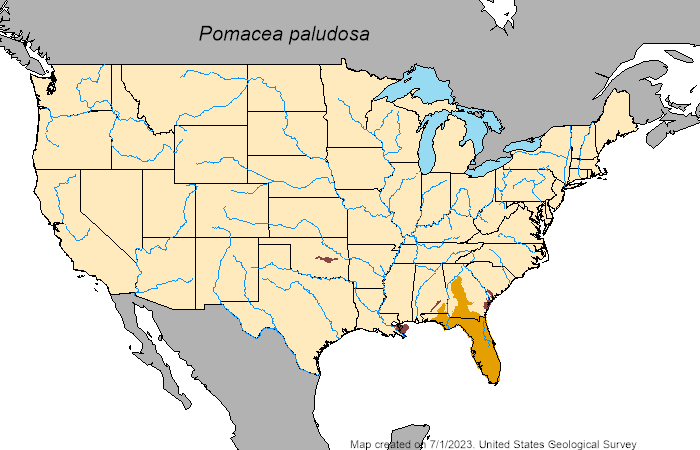

…now look at the latest U.S.G.S. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species map showing the ranges (in brown) of established populations of non-native Chinese Mystery Snails…

…and now imagine that you’re a happy-go-lucky Limpkin working your way up the Atlantic Coastal Plain toward Pennsylvania and taking advantage of the abundance of food and sunshine that summer brings to the northern latitudes. It’s a new frontier. Introduced populations of Chinese Mystery Snails are like having a Waffle House serving escargot at every exit along the way!

Be sure to click the “Freshwater Snails” tab at the top of this page to learn more about the Chinese Mystery Snail and its arrival in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Once there, you’ll find some additional commentary about the Limpkin and the likelihood of Everglade Snail Kites taking advantage of the presence of Chinese Mystery Snails to wander north. Be certain to check it out.

A brief test procedure has rubbed the epithelial cells in one of your editor’s critical organs the wrong way, thus prompting them to let loose with cytokine proteins all over his body. Shortly put, it’s like experiencing the aftermath of a major heart attack for a second time. We’ll be back when the action-packed reenactment is over.

The gasoline and gunpowder gang’s biggest holiday of the year has arrived yet again. Where does all the time go?

In observance of this festive occasion, we’ve decided to take a look at all the stuff that’s floating around in the atmosphere before all the motor travel, celebratory fires, and exciting explosions get underway.

We’ll start with the smoke from wildfires in Canada…

If you think that smoke accounts for all the particulate matter now obscuring skies in the northern half of the western hemisphere, then have a gander at this…

As you can see, natural processes are currently providing a plentiful load of particulates in our skies. There’s no real need to aggravate yourself and the situation by sitting in traffic or burning your groceries on the barbecue. And you can let those cult-like homeowner chores for later. After all, running the mower, whacker, and blower will only add to the airborne pollutants. While celebrating this Fourth of July, why risk mangling fingers on your throwing hand or catching the neighbor’s house on fire when you could just relax and quietly eat ice cream or watermelon? Yeah, that’s more like it.