HISTORICAL SUMMARY OF THE FRESHWATER GASTROPODS OF THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER

AN ANNOTATED LIST OF THE SPECIES

WITH EMPHASIS ON THE WATERS SURROUNDING CONEWAGO FALLS IN DAUPHIN, LANCASTER, AND YORK COUNTIES IN PENNSYLVANIA

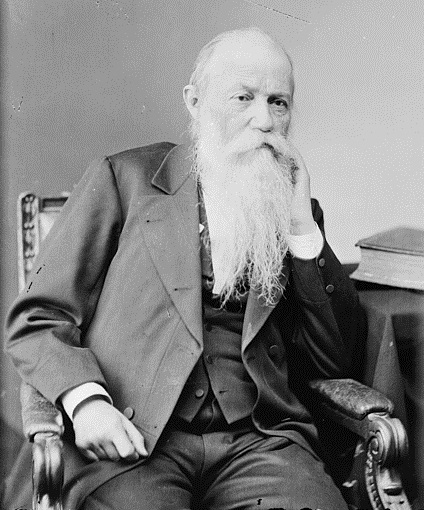

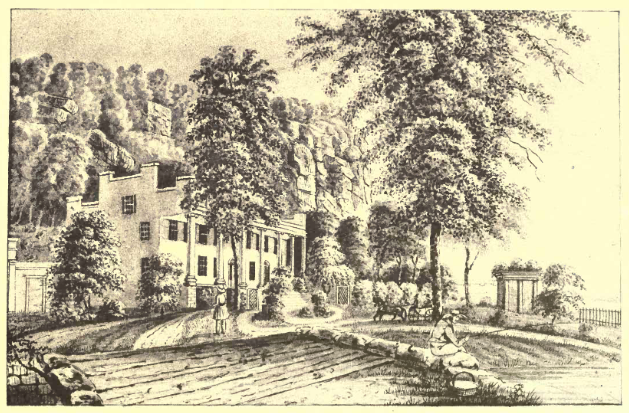

The study of freshwater gastropods on the lower Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania has its origins in one of the legends of early North American malacology, Samuel Steman Haldeman (1812-1880). Haldeman was born and raised on the banks of the Susquehanna in Locust Grove, just one mile downstream of the village of Bainbridge, and three miles below Conewago Falls in Lancaster County. There, a youthful Samuel studied natural history and initiated a life-long passion for self-education.

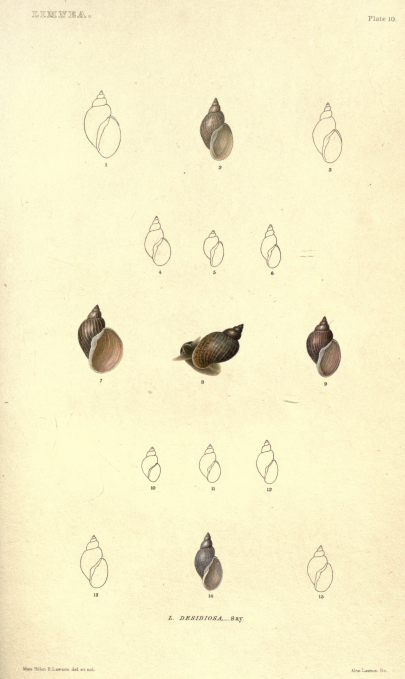

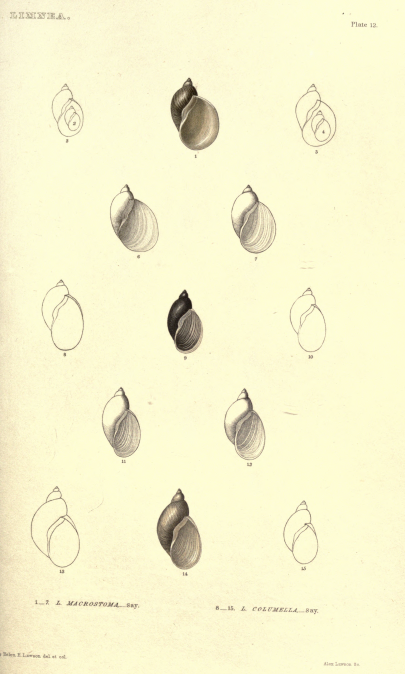

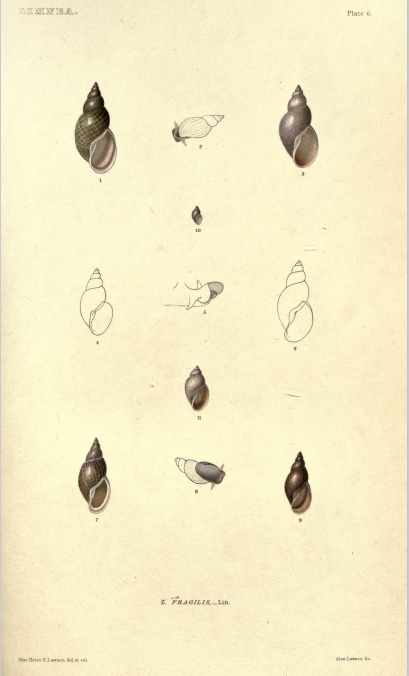

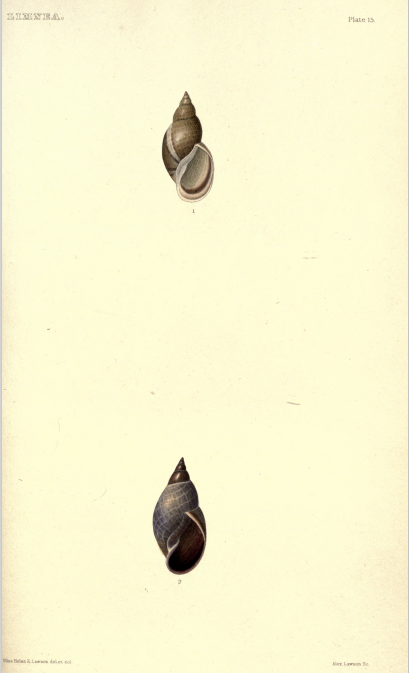

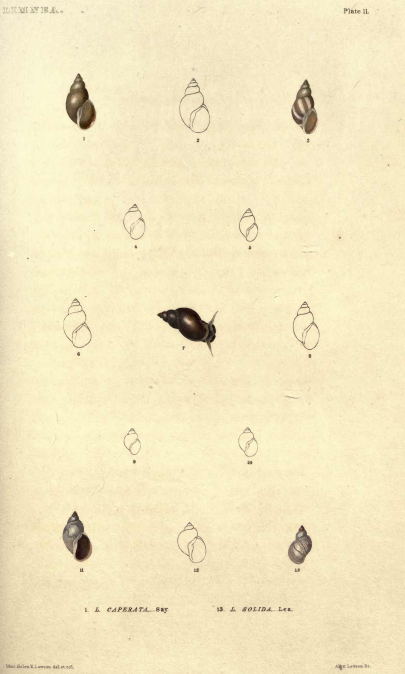

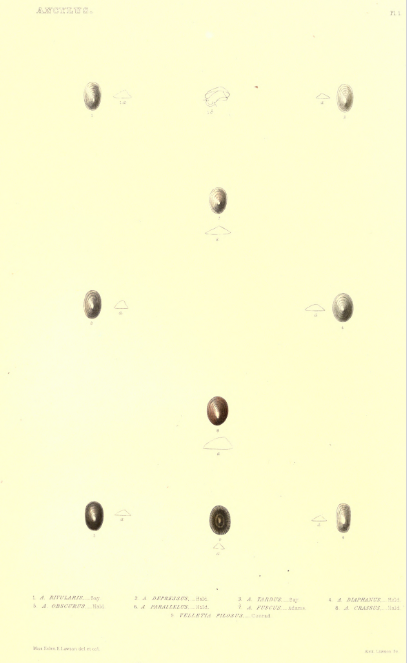

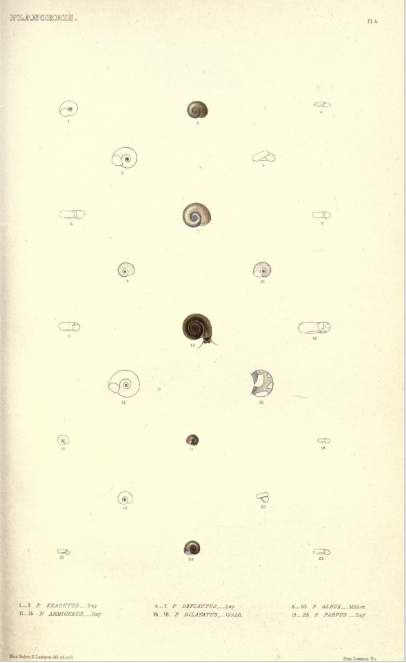

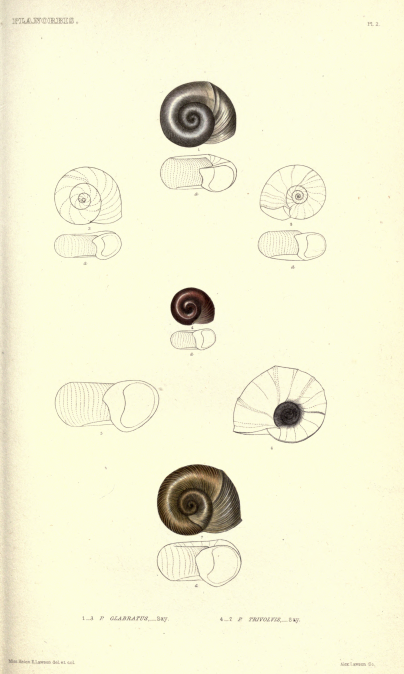

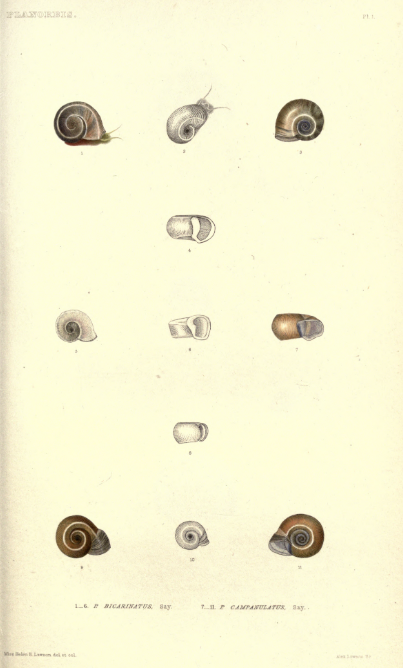

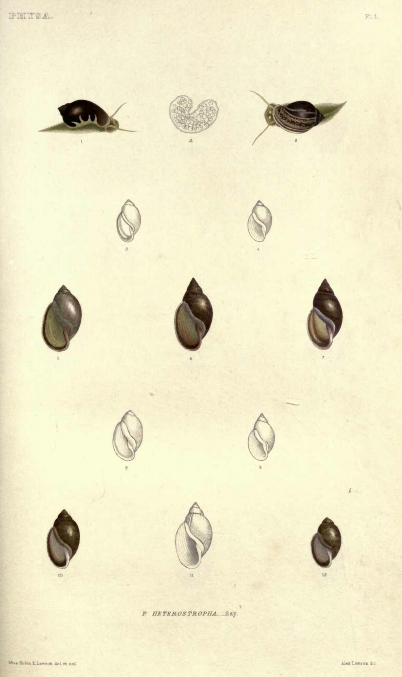

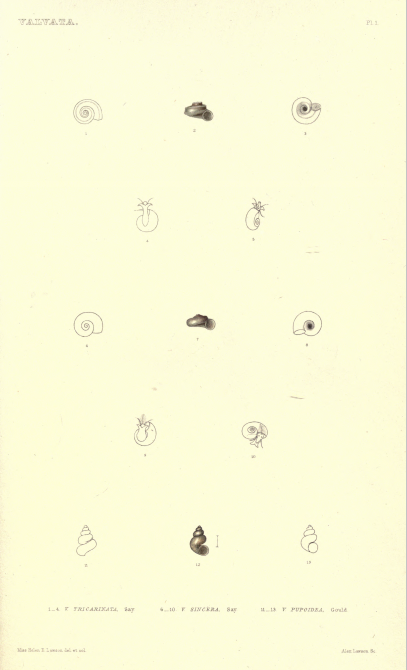

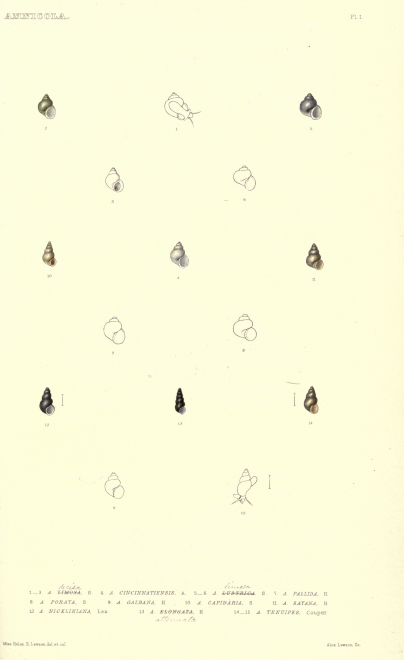

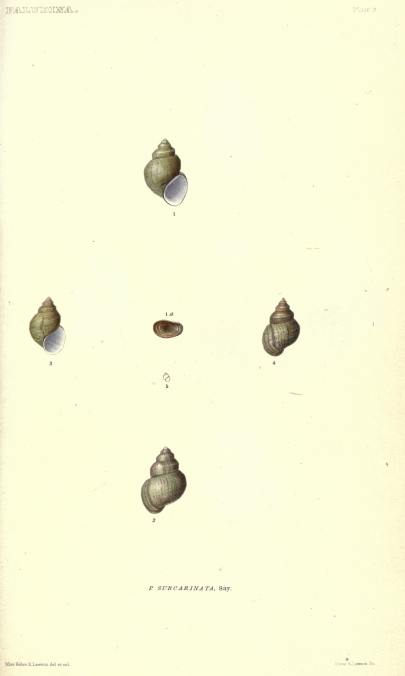

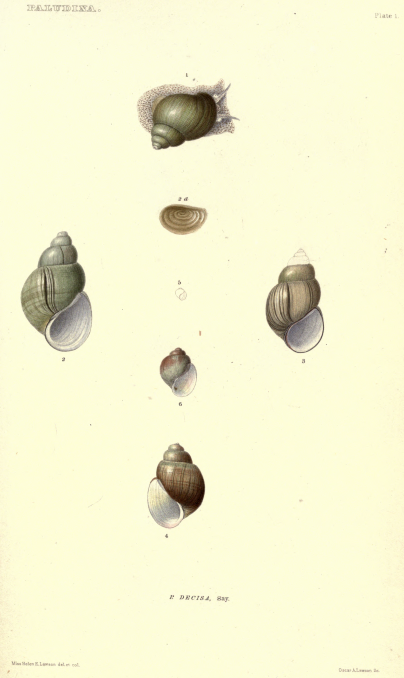

Despite leaving his studies at Dickinson College early, Haldeman became renowned as a scholar and prolific writer with a broad spectrum of expertise. His early studies of the freshwater mussels and snails on the Susquehanna River near his home were chronicled in his account of the “Molluscs” published in “Rupp’s History of Lancaster County” in 1844. Haldeman’s Monograph of the Freshwater Univalve Mollusca of the United States, the country’s first comprehensive study of freshwater snails, was being published during this time. It was mailed to subscription patrons over a four-year period from 1842 to 1845. The monograph was a momentous undertaking—often basing identification of species upon minute morphological details. This landmark work on univalve gastropods included 39 color plates meticulously illustrated by Miss Helen E. Lawson (born ca. 1808) and engraved by her family’s Philadelphia firm. Lawson’s accuracy created a sensation among academics in the field of zoology and secured her reputation as a scientific illustrator. Tragedy struck in January of 1853 when Lawson succumbed to tuberculosis while in the prime of her career.

In 1844, Haldeman published Enumeration of the recent Freshwater Mollusca which are common to North America and Europe: with Observations on Species and their Distribution. Charles Darwin, in the preface of Origin of Species (1859), would comment on Haldeman’s article, “…Professor Haldeman has ably given the arguments for and against the hypothesis of the development and modification of species: he seems to lean towards the side of change.”

Haldeman, like Darwin and other naturalists of the early nineteenth century, was absorbed into Linnaean taxonomy and was strongly influenced by Sir Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, a work which focused the attention of science on the significance of the presence of fossils within the strata of rock as a chronicle of life on earth. Haldeman took a job assisting his former Dickinson instructor Professor Henry Rogers conducting geological surveys of New Jersey and Pennsylvania in 1836, and Darwin took a copy of Principles of Geology along on the survey voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle (1831-1836). Both came to respectfully question Lyell’s ideas on the permanence of species, as well as aspects of Lamarckian inheritance—the passing from parent to offspring the physical characteristics acquired through use and disuse during a lifetime. Haldeman’s paper ponders cases for and against Lamarckian theory.

Sir Charles Lyell and Darwin came to be friends and by 1859, Lyell was reviewing Origin of Species prior to publication. In a letter to Sir Charles Lyell, dated June 21, 1859, Charles Darwin wrote:

“It was extremely kind of you to take so much trouble to tell me about Haldeman’s paper, which I read several years ago & abstracted, & I have just looked at my abstract. I well remember thinking it a very clever paper; but I did not find much of any actual use to me. I think I have quoted him in my large Book about ranges of varieties; but in my present condensed volume, I have not alluded to the paper. The speculations approach mine & (Alfred Russel) Wallace’s, but did not on any point seem to me identical. Some remarks on the young of some fresh-water shell struck me most, apparently a modified sea-mollusc.” (Darwin Correspondence Project—Letter 2470)

The last line of this correspondence is a reference to Haldeman’s speculation on how a Melania snail might adapt as a species to a gradual influx of salt water into its freshwater stream environment.

Darwin’s closest associate, botanist Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, was also reviewing Origin of Species and had also called Darwin’s attention to Haldeman’s paper. In a letter to Hooker dated July 2, 1859, Darwin commented:

“I read some years ago & abstracted Haldeman’s paper…it did not attempt, I believe, to explain adaptations & this point has always seemed to me the turning point of the theory of Natural Selection…” (Darwin Correspondence Project—Letter 2475)

In a letter to Sir Charles Lyell written on February 4, 1860, after Darwin had reexamined a copy of Haldeman’s paper that he had obtained from the Royal Society of London, Darwin wrote:

“…I have just got Haldeman from Royal—it is perplexing to know what he thinks.” (Darwin Correspondence Project—Letter 2487f)

Ultimately, Darwin would refer to Haldeman’s Enumeration of the recent Freshwater Mollusca which are common to North America and Europe: with Observations on Species and their Distribution in the American edition of Origin of Species. Darwin’s comments would be included in “The Historical Sketch of the Progress of Opinion on the Origin of Species”, which he was preparing at the time. This sketch is often included as the appendix section in modern copies of Origin of Species.

This summary has as its foundation the records of gastropods in the lower Susquehanna River watershed reported by Haldeman in his monograph (1842-1845) and in his list of “Molluscs” in “Rupp’s History of Lancaster County” (1844). Species records from H. G. Bruckhart’s 1869 list of the Mollusca collected in Lancaster County provide a continuum to the natural history timeline. Species and relative abundance lists from macroinvertebrate and benthic sampling in the Susquehanna River in the proximity of Conewago Falls (Teitt, 1997) provide a glimpse at gastropod populations during the period 1974 through 1990. The author has added anecdotes on distribution and abundance gathered while observing and exploring the Susquehanna in the area of Conewago Falls since 1979. Taxonomy has been updated using nomenclature from J. B. Burch’s Freshwater Snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of North America of 1982. Final binomial nomenclature, taxonomic order, and common names are largely derived from the “Checklist of the Freshwater Snails (Mollusca:Gastropoda) of Pennsylvania, USA” (Evans and Ray, 2008) to create an annotated list more than one hundred and seventy-five years in the making.

Domain-Eukaryota

Kingdom-Animalia

Phylum-Mollusca

Class-Gastropoda

Subclass/Clade-Heterobranchia

Family-Lymnaeidae

Marsh Fossaria Fossaria humilis

Fossaria humilis was reported in Lancaster County by Haldeman (1844) as Limnea humilis and subsequently by Bruckhart (1869) as Limnophysa humilis. Haldeman in his monograph (1842-1845) observes, “Found upon damp ground near water, or upon muddy flats left by the receding water. It is difficult to retain them in confinement, on account of their dislike to living in the water; and they accordingly pass over the edge of the vessel in which they may be placed, and move off to the distance of several feet, upon a dry surface…The short thick shells constitute the humilis of Say, and are common on the Susquehanna.” Sampling around Conewago Falls found Fossaria humilis in the period 1974 and 1980 (Teitt, 1997).

Rock Fossaria Fossaria modicellus

Using the name Limnea modicellus, Haldeman (1842-1845), in his monograph, considered this snail a dark-shelled form of Limnea humilis. Haldeman (1844) when describing Limnea humilis remarked, “…A slender variety, considered a distinct species by some authors; has been named L. medicella.” Burch (1982) classifies this snail species as Fossaria modicellus in a Fossaria obrussa group, separated completely from Fossaria (Limnea) humilis. Haldeman (1844) and Bruckhart (1869) both reported finding this snail in Lancaster County.

Golden Fossaria Fossaria obrussa

Limnea desidiosa, a form of Fossaria obrussa, was described by Haldeman (1842-1845) in his monograph. Haldeman detailed his collection of Limnea desidiosa specimens along the Susquehanna in Lancaster County; “Those…are from a pond of spring water twenty feet in diameter and two feet deep, on the Susquehanna, near my residence (Chiques Rock between Marietta and Columbia). It is subject to desiccation in very dry seasons, and has a bottom of mud, and but little vegetation, which is chiefly confervoid. The soil is slightly calcareous. I am thus particular, because this pond appears very favourably adapted to the growth of these animals, as well as Physa heterostropha and Planorbis bicarinatus.” Haldeman also collected the species from “gutters along the road above Columbia”, presumably on Chiques Rock. Recent specimens of Fossaria from Conewago Falls appear to be Fossaria obrussa.

Pygmy Fossaria Fossaria parva

A small species of Fossaria (less than 7 mm), this snail is indicated by Burch (1982) to have geographic range including the lower Susquehanna watershed.

American Ribbed Fluke Snail Pseudosuccinea columella

This species closely resembles the terrestrial Succinea snails. Haldeman (1842-1845) theorized that Pseudosuccinea columella occurred in Lancaster County, “…Limnea columella, a species which will probably be detected hereafter in the county, as it occurs in other parts of the state, as in the vicinity of Philadelphia and in York County.”

Big-eared Radix Radix auricularia

Also known as the European Ear Snail, this Eurasian species is found in mud-bottomed bodies of water with little or no current. The United States Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species website (Fuller, 2009b) lists a Radix auricularia collection record from the Little Conestoga River on the west side of Lancaster City dated 1974. This species, like many other freshwater pulmonate snails, easily hitches a ride along with translocated aquatic plant material; therefore, it may have found its way into other Lower Susquehanna watershed ponds and streams as well.

North American Palustris-like Snail Lymneus elodes

As Limnea palustris, Haldeman (1844) describes the North American Palustris-like Snail, “…shell brown, oblong conic, with six whirls, the surface frequently marked with elevated lines-length about an inch. It is a European species, but those of this country were named L. elodes, by Say, under the impression of their being a distinct species.” Limnea palustris is included as a synonym of Limnea fragilis in Haldeman’s monograph (1842-1845). It is one of the species mentioned in his 1844 paper Enumeration of the recent Freshwater Mollusca which are common to North America and Europe: with Observations on Species and their Distribution. Burch (1982) classifies all palustris-like snails under Thomas Say’s original name for North American snails resembling the European palustris, Lymneus elodes. The North American Palustris-like Snail is also known as Lymnaea elodes and Stagnicola elodes.

Wrinkled Marshsnail Stagnicola (Hinkleyia) caperata

Haldeman (1842-1845) described this species as Limnea caperata in his monograph as “…dark colored, approaching black, very minutely and sparsely dotted with whitish, which is scarcely perceptible, except between the eyes.” Haldeman’s specimens were, “…collected from a spring of shallow running water, subject to being dried up, and flowing into the Susquehanna at Marietta, Pennsylvania. The bottom is a deep bed of black tenacious mud, covered with grass.”

Family-Planorbidae

Creeping Ancylid Ferrissia rivularis (including Ferrissia tarda)

Also called Coolie Hat Snail, River Limpet and Brook Freshwater Limpet, this species was reported by Haldeman (1844) as Ancylus rivularis and “found attached to stones under water” in Lancaster County. The Creeping Ancylid is common in streams and in the Susquehanna. It is often found crawling and feeding on the shells of expired and live Unionidae mussels and sometimes on submerged rubbish in flowing water.

Haldeman (1842-1845) described Ferrissia tarda using the taxa Ancylus tardus, listing the range of this tiny snail as “the Wabash, and in Vermont”. Bruckhart (1869) reported finding it in Lancaster County. Ferrissia tarda was listed in studies on the Susquehanna around Conewago Falls in the period 1974 through 1980 (Teitt, 1997). Basch (1963) says of Ferrissia tarda, “This species has been the subject of a great deal of confusion for over a century. In particular, the distinction between rivularis and tarda has never been clear. In museum material, I have been unable to find any perceptible differences between lots of specimens preserved under each of these two names. I believe it best to consider all of these river limpets under the single species rivularis”.

The taxonomic status of the Ferrissia species continues to be the subject of research, with Dillon and Herman (2009) making the case for one species, Ferrissia rivularis, in North America. More recently, Walther, Burch and O’Foighil (2010) provide evidence of two species, Ferrissia rivularis and Ferrissia fragilis on the continent.

Dillon (2010) describes the distribution of these two species in the Potomac watershed where Ferrissia fragilis was originally believed to be restricted to slow vegetated waters of the lower piedmont and coastal plain and Ferrissia rivularis was the inhabitant of rocky streams. New knowledge places Ferrissia fragilis in nearly all waters of the southern Atlantic drainages including the rocky waters of the Blue Ridge. Ferrissia rivularis is limited to the tributaries of the Potomac in northern Virginia and “ranging south up the Great Valley into the upper James and Roanoke drainages”. This new information may call the identity of the Ferrissia found in the Lower Susquehanna watershed into question.

Dusky Ancylid Laevapex fuscus

Using the nomenclature Ancylus fuscus, the Dusky Ancylid was first described in 1841 by naturalist Charles Baker Adams. Haldeman (1842-1845) noted its distribution at the time, “Inhabits Fresh Pond, near Harvard, Massachusetts.” Laevapex fuscus is more of a lentic species than the lotic Ferrissia rivularis, a snail of flowing waters.

Flexed Gyro Gyraulus deflectus

As Planorbis deflectus, Haldeman (1842-1845) described the range of this species to include New England, Ohio, and the Northwest Territory (of the United States). Bruckhart (1869) reported the species within Lancaster County using the name Gyranlus deflectus.

Lesser Ram’s Horn Gyraulus parvus

Haldeman (1844) listed the snail as Planorbis parvus to be “less than ¼ inch” and “more rarely found” than Helisoma anceps within Lancaster County. In his monograph, Haldeman (1842-1845) comments, “Its smaller transverse diameter, and the more open concavity of the left side, distinguish it from small specimens of P. deflectus…” Bruckhart (1869) reported the species within Lancaster County as Gyranlus parvus. Gyraulus parvus can be found among organic matter in shallow waters of the Susquehanna. In 2003, it was found among the flooded parts of Common Cattail (Typha latifolia) in a pond in the Conewago Creek watershed of Lancaster County. Like the Valvatidae, Hydrobiidae, and Ancylidae, the Lesser Ram’s Horn can be easily overlooked due to its small size. It is also known by the common name Ash Gyro.

Three-whorled Ram’s Horn Planorbella trivolvis

Haldeman (1842-1845) described this species as Planorbis trivolvis, listing the geographical range to include New England, New York, Lake Erie, and the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. Later in the century, Bruckhart (1869) reported it in Lancaster County as Helisoma trivolvis. Planorbella trivolvis is a frequent transient on aquatic plant material today. The Three-whorled Ram’s Horn occurs in the Susquehanna and its tributaries and is often common in ponds and garden pools. In Bruckhart’s time, the Pennsylvania Canal along the Susquehanna, despite boat traffic, became a linear garden for many imported and native wetland plants. The canal may have provided the means and the route for this snail to find its way into Lancaster County.

Keeled Ram’s Horn Helisoma anceps

As Planorbis bicarinatus, Haldeman (1844) called the Keeled Ram’s Horn the most common species of “Planorbis” in Lancaster County. Haldeman in his monograph (1842-1845) observed, “This very common species inhabits quiet waters, along the surface of which it may be frequently seen moving in an inverted position. Its food is mud, impregnated with vegetable matter.” Bruckhart (1869) listed it using identical nomenclature. Burch (1982) uses classification including Planorbis bicarinatus in the species Helisoma anceps. This species is common in streams, including the Conewago Creek in Dauphin, Lancaster and Lebanon Counties. It is not as regular in the faster waters of the Susquehanna. Populations of Keeled Ram’s Horn probably increase in the presence of aquatic plants.

Family-Physidae

Pumpkin Physa Physella ancillaria

Haldeman (1842-1845) described specimens of Physa ancellaria from the Schuylkill/Delaware Rivers but not from the Susquehanna. The species was listed as Physa ancillaria by Bruckhart (1869) in his inventory of Lancaster County Mollusca.

Tadpole Physa Physella gyrina

Haldeman (1842-1845) wrote a description of Physa gyrina using specimens forward to him from Indiana and Ohio. Burch (1982) includes the Susquehanna watershed in the range of the species.

Acute Bladder Snail Physella (Costatella) acuta

Physella acuta was first described by French malacologist Jacques Draparnaud in 1805. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Physella acuta, a snail known at the time as the European Physa, was discovered to be expanding its range over much of the eastern hemisphere—and possibly beyond. In the vicinity of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the United States Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species website (Fuller, 2009c) listed a collection record of the Europea Physa from the Potomac River watershed in Montgomery County, Maryland, from 1974. It was assumed that the European Physa was exported from Europe and Mediterranean Africa to the eastern United States where it began spreading during subsequent decades as a non-native species. The European Physa threatened to be yet another invasive introduction from aquaria collections and inadvertent translocation (SESC Webmaster, 2011).

The abundant and widespread native gastropod Physella (Physa) heterostropha, known as the Common Tadpole Snail or Pewter Physa, was considered a near lookalike to this introduced species. Haldeman never mentioned an occurrence of the European Physa in the New World. Haldeman (1844) listed Physa heterostropha in Lancaster County as, “…our only species in this genus…” Haldeman’s monograph (1842-1845) contains commentary regarding the exclusive presence of P. heterostropha in the Susquehanna, “I have examined hundreds from the Susquehanna, and have never found one which could be confounded with the ancillaria, as it occurs in the Delaware…individuals may be confounded with P. gyrina, but these must be considered an accidental variety, as I never saw but two specimens, which are very long, and these I collected from a spring connected with the Susquehanna, which river P. gyrina does not inhabit. The posterior extremity of the labrum, is never suddenly incurved to meet the body whirl, as in P. gyrina.” Physa heterostropha was later reported in Lancaster County by Bruckhart (1869).

During the late twentieth century, the origins and the extent of the North American invasion by Physella acuta became the subject of a swelling tide of scrutiny. Genetic research by Dillon et al. (2002) determined that morphologically similar snails known as Physella acuta, Physella heterostropha, and Physella integra, the latter first described by Haldeman in 1841, are not reproductively isolated and are thus a single species—a species indigenous to North America. Because Physella acuta was the earliest of the three to be described, Physella heterostropha and Physella integra became synonyms of Physella acuta.

Populations of Physella acuta that are presently spreading throughout the eastern hemisphere as an invasive species first arrived in the Mediterranean region from eastern North America—a reverse of earlier distribution theories. These snails were transported to the Old World over two hundred years ago—more than a decade before they were described here in the eastern United States as Lymnea (Physa) heterostropha by Thomas Say in 1817. As the author of Enumeration of the recent Freshwater Mollusca which are common to North America and Europe: with Observations on Species and their Distribution in 1844, it’s a discovery that Professor Samuel Steman Haldeman would have found fascinating. All those years ago, he was surrounded by an abundance Physella acuta snails, a species found in both Europe and North America—thanks to inadvertent translocation by man.

Physella acuta, the freshwater snail long recognized as Physella heterostropha, remains widespread and abundant in the Susquehanna and most of its tributaries. The physiology of this hardy pulmonate (air-breathing) gastropod allows it to survive in waters with low levels of dissolved oxygen. It is hence often the only aquatic mollusk found in nutrient-rich and sediment-loaded waters including polluted streams, road ditches, and stormwater management impoundments. Along the Susquehanna shoreline, Physella acuta is annually abundant through the late summer and autumn. It is not unusual to find a dozen or more snails in each linear foot of water’s edge feeding upon deposits of decaying organic matter.

Family-Valvatidae

Three-keeled Valve Snail Valvata tricarinata

Haldeman (1844) called Valvata tricarinata, “our only representative of the genus in Lancaster County.” In his monograph, Haldeman (1842-1845) describes its distribution, “Inhabits New England and the Middle States…The New England specimens are smaller than those of the Middle States.” It was later collected in the county by Bruckhart (1869). The Three-keeled Valve Snail was still numerous around Conewago Falls through 1980 (Teitt, 1997), prior to the arrival of the Asiatic Clam (Corbicula fluminea).

Subclass/Clade-Caenogastropoda

Family-Bithyniidae

Faucet Snail Bithynia tentaculata

The Faucet Snail, also known as the Mud Bithynia, is an alien species native to Europe. It was reported between 1974 and 1980 in the Susquehanna near Conewago Falls (Teitt, 1997). It is apparently not common in the lower Susquehanna.

Family-Hydrobiidae

Buffalo Pebblesnail Gillia altilis

Gillia altilis was reported by H. G. Bruckhart (1869) within Lancaster County without particulars. A specimen of Gillia altilis in the collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia from Columbia, Pennsylvania, was cataloged 24 February 1916 (ANSP 122169).

Shale Pebblesnail Somatogyrus pennsylvanicus

Burch (1982) includes Columbia, Pennsylvania, as one of the few sites for the species, citing Walker (1904).

Boreal Marstonica Marstonia lustrica

According to Burch (1982), this species was first described by Thomas Say as Paludina lustrica. Haldeman (1844) listed it as a species found in Lancaster County and used the name Amnicola lustrica. Compared to Amnicola limosa, he described the species as, “…more nearly globular, the aperture is circular, and the base of the shell presents an opening.” Bruckhart (1869) listed Haldeman’s record as Potatiopsis lastrica, but did not collect the snail in Lancaster County at that time. Debate continued in recent decades as to whether the species belongs to the genus Lyogyrus, or may be part of Lyogyrus walkerii. Henry A. Pilsbury’s Marstonia lustrica is nomenclature used by Burch (1982) and here. Marstonia lustrica is a species of waters northwest of the Susquehanna basin and is more likely to be expected there.

Family-Amnicolidae

“Hydrobia” Amnicola decisa

In his monograph, Haldeman (1842-1845) says of Amnicola decisa and the preceding species, Marstonia lustrica, “…where I have observed them, (they) live upon the inferior surface of stones in running water.” Burch (1982) quotes Haldeman from 1845 describing the range of Amnicola decisa as, “Tributaries of the Susquehanna River and Schuylkill River.” Neither Haldeman (1844) nor Bruckhart (1869) directly list Amnicola decisa among the fauna of Lancaster County.

Miry Hydrobia Amnicola limosa

The Miry Hydrobia is the numerous member of the Hydrobiidae family in the lower Susquehanna River. Haldeman (1844) describes Amnicola limosa, “…a miniature representation of Paludina, Amnicloa limosa is one eighth of an inch long, and resembles Paludina decisa, but the aperture is proportionally wider.” Surveys around Conewago Falls (Teitt, 1997) show a decline in numbers between 1980 and 1990 coinciding with the arrival and population expansion of the Asiatic Clam (Corbicula fluminea). The abundance of Miry Hydrobia and other members of the Hydrobiidae family may be favorably impacted by the presence of aquatic vegetation.

Squat Duskysnail Amnicola (Lyogyrus) grana

Haldeman (1844) listed the species in Lancaster County as Amnicola granum, and found it, at one twentieth of an inch, “the smallest freshwater shell.” Haldeman did not particularly assign it to the Susquehanna River, but in his monograph (1842-1845) quoted Thomas Say, “This very small species is found in plenty in the fish ponds at Harrowgate, (near Philadelphia,) crawling on the dead leaves which have fallen to the bottom of the water.”

Family-Tateidae

New Zealand Mud Snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum

A potentially invasive species in the lower Susquehanna basin, the New Zealand Mud Snail is currently spreading throughout the Great Lakes and much of the western United States. Developing embryos are already within the reproductive systems of the asexual females upon birth, thus expediting population expansion. Densities can exceed 300,000 per square meter. This species may have found transit into the United States with imported trout (SESC Webmaster, 2011). The United States Geological Survey (Benson, et al., 2021) lists the first reports of the New Zealand Mud Snail in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed—in the headwaters of Codorus Creek in York County, Pennsylvania, (Specimen ID 1655263) and in Trindle Spring Run in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania (Specimen ID 1657343). Both records occurred in trout-stocked waters in 2020.

Family-Pleuroceridae

Virginian River Horn Snail Elimia (Pleurocera/Goniobasis) virginica

Haldeman (1844) wrote of the species in Lancaster County, “At the head of our Mollusca, the genus Melania may be placed. It contains but a single species, Melania virginica, which occurs throughout the Susquehanna, and in many of the larger streams. The shell is an inch long, with eight or ten turns; the color green, with two spiral reddish bands, in some individuals.”

The recent decades have seen fluctuations in the abundance of the Virginian River Horn Snail. Elimia virginica was by far the most abundant of benthic gastropods in sampling conducted around Conewago Falls in 1980. Of the Mollusca, only the Sphaeriidae clams were more numerous. Ten years later, sampling in 1990 found an expanding population of newly arrived Asiatic Clams (Corbicula fluminea). Though still present and well-distributed, Elimia virginica was not found during the 1990 sampling. Sphaeriidae clams remained numerous in the 1990 samples (Teitt, 1997). During the decade of the 1990s, the Asiatic Clams became the conspicuous and most abundant mollusk on the lower Susquehanna River. Elimia virginica remained common, but sometimes difficult to detect. Visual assessments conducted in daylight may miss the species during periods when they are feeding nocturnally.

In the summer and autumn of 2010 there was a resurgence of Elimia virginica in the Susquehanna downstream of Conewago Falls. Low river gauge stages (below 3.5 feet at Harrisburg) with minor fluctuation and lower than normal siltation, led to a year with denser growths of aquatic and emergent plants, perhaps among the best in thirty years. American Eelgrass (Vallisneria americana) and Water Stargrass (Heteranthera dubia) thrived in the ideal conditions. The water quality factors leading to improved plant production, if not the presence of the plant communities themselves, seemed to favor improved densities of Elimia virginica, often seen exceeding one dozen snails per square meter of river substrate. This impressive sight was witnessed from Conewago Falls to areas downstream at least two miles away, and was probably widespread on the lower Susquehanna, providing the opportunity to observe tens of thousands of snails. The numbers rivaled those, at least temporarily, of the invasive Asiatic Clam.

River Snail Leptoxis carinata

Previous names for the River Snail include Mudalia carinata and Spirodon carinata. Haldeman (1844) wrote of this species, “belonging to the allied genus Anculosa, and called, from the dissimilarity of the various individuals, Areculosa dissimilis. Length half an inch.” Bruckhart (1869) found the species in Lancaster County and reported it as Leptoxis dissimilis. Though it is known by the common name River Snail, this species has been found to thrive more often in pond or quiet pool situations. It is common in Conewago Creek in Dauphin, Lancaster, and Lebanon Counties, sometimes detected by sifting sandy substrate. The River Snail is uncommon in the Susquehanna but can be found at Conewago Falls among the pools of the diabase pothole rocks and in channels downstream. It is also known by the common name Crested Mudalia.

Family-Viviparidae

Japanese Mystery Snail Cipangopaludina (Bellamya) japonica

The Japanese Mystery Snail is a non-native species commonly found as an escape or introduction from aquaria and garden pools. The adult Japanese Mystery Snail has small ridges called “carinae” on the spiral of the shell. This gastropod reaches about two inches in length and is difficult to differentiate from the non-adult Cipangopaludina (Bellamya) chinensis, the Chinese Mystery Snail—a species with which it may be synonymous. Cipangopaludina are the largest of the freshwater snails found in the lower Susquehanna watershed. As their family name suggests, they are viviparous—retaining their eggs and giving birth to live young.

In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the United States Geological Survey (R. M. Kipp, et al., 2021) lists established populations of the Japanese Mystery Snail in Conodoguinet Creek in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, (since 2004) and in the main stem of the river in Lake Frederic at Bashore Island, just upstream of the York Haven Dam and Conewago Falls (since 2013).

Chinese Mystery Snail Cipangopaludina (Bellamya) chinensis

The Chinese Mystery Snail is similar in appearance to the Japanese Mystery Snail. The shell of the former is differentiated from that of the latter using one principle attribute—it lacks carinae ridges and instead appears “dented”. However, young Chinese Mystery Snails, those less than two inches in length, may exhibit considerable carinae ridges. Though the United States Geological Survey currently recognizes them as distinct species, Cipangopaludina (Bellamya) japonica may in time be recognized as a synonym of Cipangopaludina (Bellamya) chinensis. In the aquarium trade, in water-gardening circles, and elsewhere, both animals are known under the collective name “Oriental Mystery Snail” (Cipangopaludina species). A less frequently used colloquial name is “Trapdoor Snail”.

The United States Geological Survey (Fuller, 2009a) records collection of the Chinese Mystery Snails at numerous locations in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. As early as 1965, the species was found at Lake Duffy in the Conewago Creek watershed in Lebanon County (Specimen ID 52315) and at “Herr’s Ice Dam” in Lancaster (Specimen ID 52314). In later years the snail was collected at Wildwood Lake in Harrisburg, both in 1993 (Specimen ID 50379) and again in 2002 (Specimen ID 154701). Also in 2002, the species was collected in the main stem of the Susquehanna River not far from the Wildwood Lake location (Specimen ID 154700).

In the summer of the year 2000, before the impoundment was permanently drained, several Chinese Mystery Snails were collected by the author from the long-established population at Lake Duffy. Then, during the summer of 2011, specimens were found reproducing in the Susquehanna in the area of Conewago Falls and in river waters downstream. The snails at Conewago Falls could have arrived as a new introduction, as an extension of the Lake Duffy colony, or as an expansion of the upstream population at Wildwood Lake and adjacent waters of the Susquehanna at Harrisburg. Regardless of their mode of distribution, Chinese Mystery Snails are a species now widely established in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

A new population of Chinese Mystery Snails in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area prompted the first Limpkin ever recorded in Pennsylvania to linger there in July, 2023. The Limpkin is a tropical marsh bird resembling a small crane or large rail.

Like the Snail Kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis), the home range of the Limpkin closely approximates the combined ranges of the Florida Applesnail (Pomacea paludosa) and similar large tropical ampullariid mystery snails—Florida south through the Carribean Islands into most of South America. Both the Limpkin and the Snail Kite have bills specifically adapted for removing the bodies of ampullariid mystery snails from their curved shells, thus both birds are largely dependent on the presence and availabilty of these native mollusks for their survival.

The establishment of numerous non-native populations of “Oriental Mystery Snails” (Cipangopaludina) along the Atlantic Slope during recent decades may have enabled the vagrant Limpkin that found its way to Middle Creek to wander north from Florida while sustaining itself on these large non-native snails which happen to be compatible with the bird’s highly specialized feeding adaptation. One might say that for a traveling bird, they make a suitable substitute for applesnails.

Note in the photograph how the Limpkin is able to grasp the rim of the Chinese Mystery Snail’s shell opening, or possibly its “trapdoor” (operculum), with the tweezers-like tip of its bill. Within seconds the bird placed its victim in shallow water and pulled the body from its shell for consumption. The bird made the process look easy.

Will Snail Kites also begin wandering north as vagrants in response to the presence of introduced populations of “Oriental Mystery Snails”? One delighted bird enthusiasts on Presque Isle in Erie County, Pennsylvania, during October, 2019, but don’t expect a trend. The applesnails upon which Snail Kites feed have both a gill and a lung structure for breathing, so they are quite amphibious. Snail Kites prey on applesnails primarily when they approach the surface to breath air through their siphon or when they leave the water while climbing aquatic vegetation. The non-native “Oriental Mystery Snails” possess only gills, so are found out of the water and vulnerable to kites only when stranded by drought conditions. To survive for just a limited amount of time, they can seal up their “trapdoor” (operculum) for protection from the drying effects of the open air, but they thrive only as an underwater inhabitant—hardly ideal prey for a kite.

Of the two species of non-native “Oriental Mystery Snails” currently found in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the viviparid univalves we presently identify as Cipangopaludina (Bellamya) chinensis, the Chinese Mystery Snails, appear to be more widespread and numerous than those we identify as Cipangopaludina (Bellamya) japonica, the Japanese Mystery Snails. Not surprisingly, other non-idigenous viviparids may soon join their ranks. The Banded Mystery Snail (Viviparus georgianus) of the southern Gulf States and Midwest and the similar “European Mystery Snail” (Viviparus viviparus) each have the potential to colonize suitable waters of the lower Susquehanna watershed from aquaria collections (SESC Webmaster, 2011).

Keeled Mystery Snail Lioplax subcarinata

Haldeman (1844) found the Keeled Mystery Snail, “smaller, rough with transverse spiral lines, of a dull light green color, and with a rounder aperture,” in comparison to the Lesser Mystery Snail. In the monograph, Haldeman (1842-1845) used the nomenclature Paludina subcarinata for the species. Bruckhart (1869) reported the Keeled Mystery Snail as Lioplex subcarinata. The Keeled Mystery Snail is numerous in some quiet pools of the river. It is more commonly encountered in streams.

Lesser Mystery Snail Campeloma decisum

Haldeman (1844) described Paludina decisa as, “found in some parts of the Susquehanna,” and, “short smooth light green shell, nearly an inch long”. In his monograph, Haldeman (1842-1845) reported the snail’s distribution included, “rarely, the Susquehanna.” Bruckhart (1869) listed Campeloma decisum as Melantho decisa. Today, the Lesser Mystery Snail is regular and common in the Susquehanna and larger tributary systems.

—L. L. Coble, 2011 (revised 2021)

SOURCES

Basch, P. 1963. “A review of the recent freshwater limpet snails of North America (Mollusca: Pulmonata)”. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 129: pp.399-461.

Benson, A. J., R. M. Kipp, J. Larson, and A. Fusaro. 2021. Potamopyrgus antipodarum (J. E. Gray, 1853): United States Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, Florida. http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?SpeciesID=1008

Bruckhart, H. G. 1869. “Conchology of Lancaster County”. J. I. Mombert’s An Authentic History of Lancaster County in the State of Pennsylvania. J. E. Barr and Company, Lancaster, Pa. pp. 517-518.

Burch, J. B. 1982. Freshwater Snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of North America. EPA-600/3-82-026, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Cincinnati, Ohio. 294 pp.

Dillon, R. T., A. R. Wethington, J.M. Rhett, and T. P. Smith. 2002. “Populations of the European freshwater pulmonate Physa acuta are not reproductively isolated from American Physa heterostropha or Physa integra“. Invertebrate Biology. 121: pp.226-234.

Dillon, R. T. and J. J. Herman. 2009. “Genetics, shell morphology, and life history of the pulmonate limpets Ferrissia rivularis and Ferrissia fragilis“. Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 24: pp.261-271.

Dillon, Dr. Rob. 8 Dec 2010. Freshwater Gastropods of North America, Two species of Ferrissia. http://fwgna.blogspot.com/2010_12_01_archive.html

Evans, R. and S. Ray. 2008. “Checklist of the freshwater snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Pennsylvania, USA”. Journal of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science. 82: pp. 92-97.

Evans, R. and S. Ray. 2010. “Distribution and environmental influences on freshwater gastropods from lotic systems and springs in Pennsylvania, USA, with conservation recommendations”. American Malacological Bulletin. 28: pp.135-150.

Fuller, Pam. 19 Aug 2009a. United States Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species, Cipangopaludina chinensis malleata. http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/collectioninfo.aspx?SpeciesID=1045

Fuller, Pam. 19 Aug 2009b. United States Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species, European ear snail (Radix auricularia)- Collection Record. http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/SpecimenViewer.aspx?SpecimenID=52462

Fuller, Pam. 19 Aug 2009c. United States Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species, Physella acuta (European physa). http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/SpecimenViewer.aspx?SpecimenID=52437

Haldeman, Samuel S. 1842-1845. A monograph of the freshwater univalve Mollusca of the United States. E. G. Dorsey, Philadelphia, Pa. 2 volumes. 231pp.

Haldeman, Samuel S. 1844. “Sketch of the natural history of Lancaster County, Penna”. Rupp’s History of Lancaster County. I. D. Rupp. Chapter XIII.

Kipp, R. M., A. J. Benson, J. Larson, and A. Fusaro. 2021. Cipangopaludina japonica (von Martens 1861): United States Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, Florida. http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?SpeciesID=1046

SESC Webmaster. 07 Jan 2011. United States Geological Survey SESC Summary Report, U.S.F.W.S. Region 5, Gastropods. http://fl.biology.usgs.gov/Region_5_Report/html/gastropods.html

Teitt, Thomas R. 1997. Personal communication. Environmental Scientist. Three Mile Island Nuclear Station, GPU Nuclear Inc., Route 441 South, Middletown, Pa. 17057

Walker, Bryant. 1904. “New species of Somatogyrus”. Nautilus. 17(12): 133-142, pl. 5.

Walther, A. C., J. B. Burch and D. O’Foighil. 2010. “Molecular phylogenetic revision of the freshwater limpet genus Ferrissia (Planorbidae:Ancylinae) in North America yields two species: Ferrissia (Ferrissia) rivularis and Ferrissia (Kincaidilla) fragilis“. Malacologia. 53: pp.25-45.