In case you haven’t already heard, the Snow Geese are at last filtering north from the Atlantic Coastal Plain to congregate at the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties.

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

In case you haven’t already heard, the Snow Geese are at last filtering north from the Atlantic Coastal Plain to congregate at the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties.

Just a reminder—there’s still time to order trees and shrubs from your local county conservation district’s annual sale, but you need to act soon…

Cumberland County Conservation District 48th Annual Tree Seedling Sale

Order by Friday, March 20, 2026

Pick Up on Thursday, April 16, 2026, or Friday, April 17, 2026

Dauphin County Conservation District Seedling Sale

Order by Monday, March 16, 2026

Pick Up on Thursday, April 23, 2026, or Friday, April 24, 2026

Franklin County Conservation District Tree Seedling Sale

Order by Tuesday, March 17, 2026

Pick Up on Thursday, April 23, 2026

Huntingdon County Conservation District Tree/Seedling Sale

Order by Friday, April 3, 2026

Pick Up on Thursday, April 16, 2026, or Friday, April 17, 2026

Lancaster County Conservation District Annual Tree Seedling Sale

Order by Friday, March 6, 2026

Pick Up on Friday, April 10, 2026

Lebanon County Conservation District ALL NATIVE! Tree & Plant Sale

Order by Monday, March 2, 2026

Pick Up on Friday, April 17, 2026

Mifflin County Conservation District Tree Sale

Order by Friday, March 6, 2026

Pick Up on Wednesday, April 15, 2026, or Thursday, April 16, 2026

Order by Saturday, March 21, 2026

Pick Up on Saturday, May 2, 2026

Snyder County Conservation District Tree Seedling Sale

Order by Monday, March 30, 2026

Pick Up on Wednesday, April 15, 2026

York County Conservation District Seedling Sale

Order by Sunday, March 15, 2026

Pick Up on Thursday, April 16, 2026

If maybe you would like to order trees but you’re not quite ready to put them in the ground, why not pot them up and start your own plant nursery. It’s a great way to build an inventory of hardy stock for planting around your own property or for use in community or civic conservation projects.

During winter’s harshest conditions, one must frequently marvel at the methods various forms of wildlife have to survive. Take a look at some of the animals we found using their life-sustaining adaptations to find food amidst the snow-covered landscape and bitter cold air.

For those of you who may be wondering if there are Snow Geese at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area, the answer is yes—just one!

So where are the thousands of Snow Geese we’ve grown accustomed to seeing during recent decades as they gather at the refuge in February while preparing to fly north for the summer?

It looks like the worst of the cold may be behind us. With temperatures trending upwards during the coming days and weeks, some species of wildlife will soon find their search for food made a whole lot easier.

With another round of single-digit and possibly sub-zero temperatures on the way, birds and other wildlife are taking advantage of a break in the extreme conditions to re-energize. During the past day, these species were among those attracted to the food and cover provided by the habitat plantings in the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters garden…

For overwintering birds and other animals, finding enough food is especially difficult when there’s snow on the ground. And nighttime temperatures in the single digits make critical the need to replenish energy during the daylight hours. Earlier this afternoon, we found these American Robins seizing the berry-like cones from ornamental junipers in a grocery store parking lot. It was an urgent effort in their struggle for survival.

County conservation district offices will soon be taking orders for their spring tree sales. Be sure to load up on plenty of the species that offer food, cover, and nesting sites for birds and other wildlife. These sales are an economical way of adding dense-growing clusters or temperature-moderating groves of evergreens to your landscape. Plus, selecting four or five shrubs for every tree you plant can help establish a shelter-providing understory or hedgerow on your refuge. Nearly all of the varieties included in these sales produce some form of wildlife food, whether it be seeds, nuts, cones, berries, or nectar. Many are host plants for butterflies too. Acquiring plants from your county conservation district is a great opportunity to reduce the amount of ground you’re mowing and thus exposing to runoff and erosion as well!

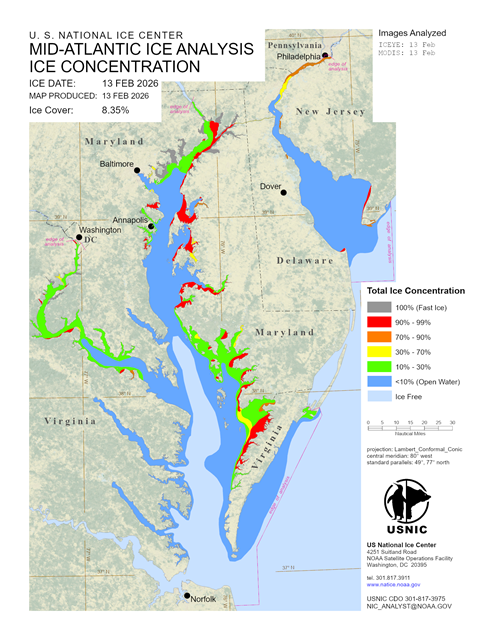

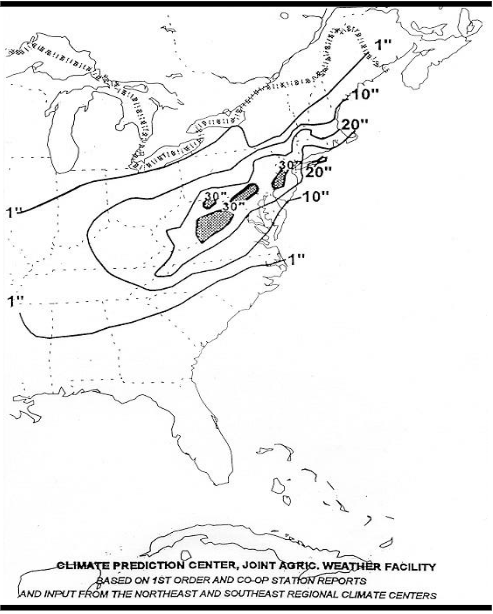

It all started rather innocently as a typically cold early January with sheets of ice covering the river and with soils on the lands in the remainder of the lower Susquehanna watershed frozen solid. Then came the “Blizzard of ’96”, blanketing much of the valley with between 20 and 30 inches of wind-driven snow.

In affected areas of Pennsylvania, Governor Tom Ridge closed all state roads for the duration of the snowfall event. Many would remain closed for much of the following week as drifting hampered exhaustive efforts to get impassable routes open.

Just as the recovery entered its second week, a change in the weather pattern took hold as milder air and spring-like rains hastened the melt. Clogged by snow often several feet in depth, storm sewer inlets and other drainage features failed to collect the runoff. Street and urban flooding became widespread. Some buildings, particular those with large flat roofs, experienced structural damage due to any remaining snow soaking up the additional weight of the rain. As local creeks swelled to stain snowy meadows brown, attention shifted to the icy river.

On the Susquehanna, rising waters started moving ice into accumulating piles of car-sized chunks behind dams and at choke points along the river’s course. During warmer weather, stream gauges provide a depth of water reference known as a stage (measured in feet) that corresponds to a rate of flow passing the gauge site (measured in cubic feet per second). On occasions when ice and debris block river channels during winter, these readings can fluctuate wildly and the relationship between stage and flow can become dubious. When the water is running ice-free at Harrisburg for example, a gauge reading of about 11.1 feet is indicated when the river flow rate is approximately 162,000 cubic feet per second. But due to its impact on the capability of the river channels to pass water, the presence of slow-moving and jammed ice can cause rapid and sometimes unpredictable variations in gauge readings, even when the flow rate remains steady. Impaired by an ice jam at the gauging station or just downriver, a flow of 162,000 cubic feet per second could lead to a stage measurement significantly higher than 11.1 feet, and the area of adjacent floodplain inundated by rising waters will increase to a corresponding degree. Conversely, a jam upstream of the gauging station could cause the reading to drop below 11.1 feet—at least temporarily—then look out, a dangerous surge could be forthcoming!

At Harrisburg, the ice jam behind the Dock Street Dam in January, 1996, caused devastating flooding in the city’s Shipoke neighborhood, on City Island, and in low-lying areas along the river’s west shore.

Downriver at Conewago Falls, ice jams behind the York Haven Dam and at several choke points within the riverine archipelago that extends from Haldeman Island to Haldeman Riffles in Lancaster County would be relieved as the river crested there during the afternoon of January 21st. The following photograph accurately relates the scene, minus the stench of mammalian feces and petroleum emanating from the polluted water of course.

You may find this hard to believe, but during the colder months in the lower Susquehanna valley, gulls aren’t as numerous as they used to be. In the years since their heyday in the late twentieth century, many of these birds have chosen to congregate in other areas of the Mid-Atlantic region where the foods they crave are more readily available.

As you may have guessed, the population boom of the 1980s and 1990s was largely predicated on human activities. These four factors were particularly beneficial for wintering gulls…

So what happened? Why are wintering gulls going elsewhere and no longer concentrating on the Susquehanna? Well, let’s look at what has changed with our four man-made factors…

GULLS THIS WINTER

Despite larid abundance on the lower Susquehanna not being the spectacle it was during the man-made boom days, an observer can still find a variety of medium and large-sized gulls wintering in the region. We ventured out to catch a glimpse of some of the species being seen both within the watershed and very nearby.

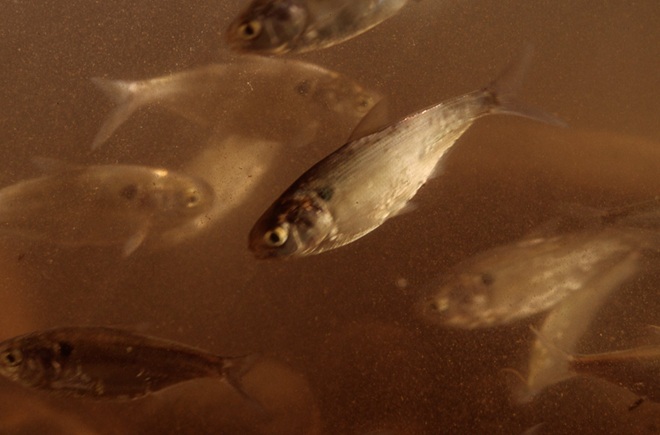

For us, seeing a Glaucous Gull brought back memories of the last time we saw the species. It was forty-five years ago on New Year’s Day 1981 that we discovered two first-winter birds feeding on Gizzard Shad in open water on an otherwise ice-choked Susquehanna below the York Haven Dam powerhouse at Conewago Falls. Hey Doc Robert, do you remember that day?

As part of an update to our “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” page, we’ve just added this chart for determining the age of the Bald Eagles you might observe on the lower Susquehanna River and elsewhere in coming weeks.

Bald Eagles in each age class often retain their fall appearance through much of the winter. However, beginning January 1st, each bird is reclassified into the next in the series of chronological plumage designations. Consequently, during the early part of the new year until a new generation of eagles is hatched in late winter and spring, there are no birds in our area designated “hatch-year/juvenile”. After fledging, these youngest eagles, the new generation of juveniles, often show little change in appearance until after their first birthday, by which time they are already classified as second-year/Basic I immature birds. For birds other than the new generation of hatch-year/juvenile eagles, the majority of the molt that produces their new autumnal appearance each year occurs during spring and especially summer, when food is abundant and the bird’s energy needs for purposes other than growing feathers are at a minimum. Hence, by the time fall migration rolls around, the next in the successive progression of plumage changes is evident. For more details and year-round images of Bald Eagles, check out our “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” page by clicking the tab at the top of this page.

Wintering Bald Eagles are again congregating on the lower Susquehanna River, particularly in the area of Conowingo Dam near Rising Sun, Maryland. To catch a glimpse of the action earlier this week, we took a drive on U.S. Route 1 atop Conowingo’s impounding structure to reach Fisherman’s Park on the river’s west shore below the powerhouse.

To the delight of photographers at Conowingo, some of the eagles can be seen grabbing fish, mostly Gizzard Shad, from the tailrace area of the river below the powerhouse. But Bald Eagles are opportunistic feeders, and their feeding habits are similar to those of numerous other birds found in the vicinity of the dam at this time of year—they’re scavengers. Here’s a glimpse of some of the other scavengers found in the midst of this Bald Eagle realm…

Here are a few more late-season migrants you might currently see passing through the lower Susquehanna valley. Where adequate food and cover are available, some may remain into part or all of the winter…

Those cold, blustery days of November can be a real downer. But there’s a silver lining to those ominous clouds, and it comes with the waves of black and mostly dark-colored migrants that stream down the ridges of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed on their way south at this time of year.

For more information on regional hawkwatching sites and raptor identification, click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page. And for more on Golden Eagles specifically, click the “Golden Eagle Aging Chart” tab.

As we begin the second half of October, frosty nights have put an end to choruses of annual cicadas in the lower Susquehanna valley. Though they are gone for yet another year, they are not forgotten. Here’s an update on one of our special finds in 2025.

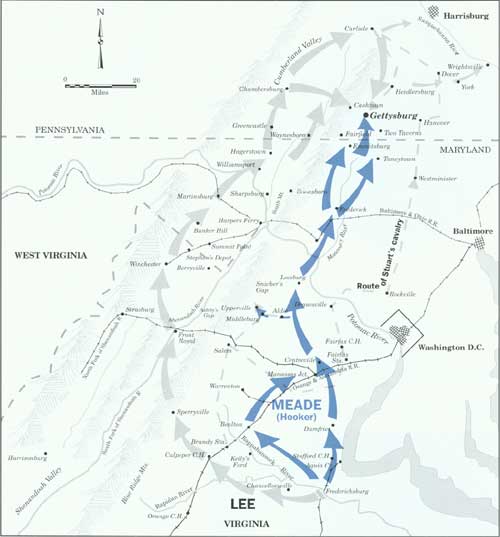

During late June of 1863, the beginning of the third summer of the American Civil War, there was great consternation among the populous of the lower Susquehanna region. Hoping to bring about Union capitulation and an end to the conflict, General Robert E. Lee and his 70,000-man Army of Northern Virginia were marching north into the passes and valleys on the west side of the river. The uncontested Confederate advances posed an immediate threat to Pennsylvania’s capital in Harrisburg and cities to the east. Marching north in pursuit of Lee was the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac, the lead element of the 100,000-man Union force under the direction of newly appointed commander General George G. Meade.

Upon belatedly learning of Meade’s pursuit, Lee hastily ordered the widely separated corps of his army to concentrate on the crossroads town of Gettysburg. As the southern army’s Third Corps under General A. P. Hill approached Gettysburg from the west, they were met by Union cavalry under the leadership of General John Buford. Dismounted and formed up south to north across the Chambersburg Pike, Buford’s men held off Confederate infantry until relieved by the arrival of the Union First Corps. As he deployed his men, the First Corps’ commander, General John F. Reynolds of Lancaster, was struck by a bullet and killed.

If you visit the Gettysburg battlefield, you can find the General John C. Robinson monument at the site of his division’s first-day position along Doubleday Avenue at Robinson Avenue near the Eternal Light Peace Memorial. But that’s not the Robinson we went to Gettysburg to see.

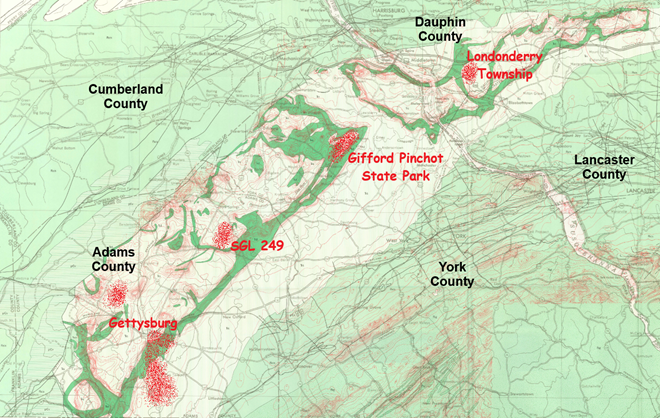

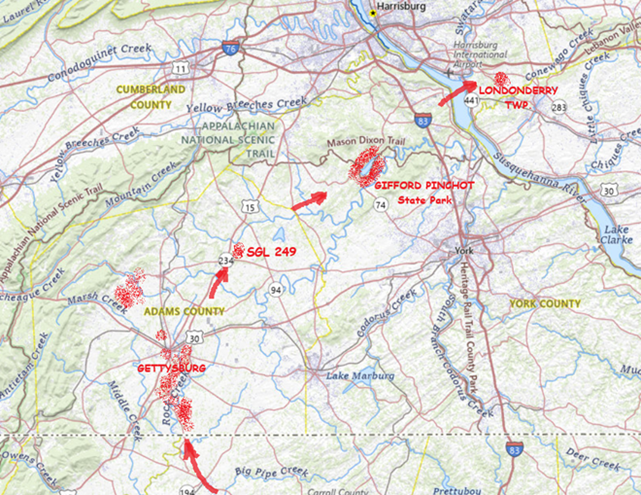

Following up on our sight and mostly sound experiences with some Robinson’s Cicadas, an annual species of singing insect we found thriving at Gifford Pinchot State Park in York County, Pennsylvania, during late July, we spent some time searching out other locations where this native invader from the southern United States could be occurring in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

During mid-August, we stumbled upon a population of Robinson’s Cicadas east of the Susquehanna in the Conewago Creek (east) watershed in Londonderry Township, Dauphin County, and made some sound recordings.

After pondering this latest discovery, we decided to investigate places with habitat characteristics similar to those at both the new Londonderry Township and the earlier Gifford Pinchot State Park locations—successional growth with extensive stands of Eastern Red Cedar on the Piedmont’s Triassic Gettysburg Formation “redbeds”. We headed south towards known populations of Robinson’s Cicadas in Virginia and Maryland to look for suitable sites within Pennsylvania that might bridge the range gap.

Our search was a rapid success. On State Game Lands 249 in the Conewago Creek (west) watershed in Adams County, we found Robinson’s Cicadas to be widespread.

Following our hunch that these lower Susquehanna Robinson’s Cicadas extended their range north through the cedar thickets of the Gettysburg Basin as opposed to hopping the Appalachians from a population reported to inhabit southwest Pennsylvania, we made our way to the battlefield and surrounding lands. We found Robinson’s Cicadas to be quite common and widespread in these areas, even occurring in the town of Gettysburg itself.

Having experienced our first frost throughout much of the lower Susquehanna valley last night, we can look forward to seeing some changes in animal behavior and distribution in the days and weeks to come. Here are a few examples…

Less than ideal flying conditions can cause some of our migrating birds to make landfall in unusual places. Clouds and gloom caused a couple of travelers to pay an unexpected visit to the headquarters garden earlier today.

Be sure to keep an eye open for visiting migrants in your favorite garden or park during the overcast and rainy days ahead. You never know what might drop by.

Crisp cool nights have the Neotropical birds that visit our northern latitudes to nest during the summer once again headed south for the winter.

Flying through the night and zipping through the forest edges at sunrise to feed are the many species of migrating vireos, warblers, and other songbirds.

As the nocturnal migrants fade into the foliage to rest for the day, the movement of diurnal migrants picks up the pace.

To find a hawk-counting station near you, check out our “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” page by clicking the tab at the top of this page. And plan to spend some time on the lookout during your visit, you never know what you might see…

Chilly nights and shorter days have triggered the autumn migration of Neotropical birds. You may not have to go far to see these two travelers. Each is a species you may be able to find migrating through your neighborhood.

Beginning this evening at about 10:44 PM EDT, and lasting until almost 11 o’clock, the gaseous clouds from two of three TOMEX+ (Turbulent Oxygen Mixing Experiment) sounding rockets launched from NASA’s Wallops Island Flight Facility near Chincoteague, Virginia, were visible in the southern skies of much of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. From susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, we were able to see and photograph the glowing clouds created by these vapor releases. Within minutes, the contrail-like wisps were swept away by the swift thin air of the mesosphere, the area lying just below the thermosphere and the Kármán Line—the border of outer space 100 kilometers (62 miles) above sea level. According to NASA, “This mission aims to provide the clearest 3D view yet of turbulence in the region at the edge of space.”

It may seem hard to believe, but the autumn migration of shorebirds and many Neotropical songbirds is now well underway. To see the former in what we hope will be large numbers in good light, we timed a visit to the man-made freshwater impoundments at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge near Smyrna, Delaware, to coincide with a high-tide during the mid-morning hours. Come along for a closer look…

Planning a visit? Here are some upcoming dates with morning high tides to coax the birds out of the tidal estuary and into good light in the freshwater impoundments on the west side of the tour road…

Tuesday, August 19 at approximately 07:00 AM EDT

Wednesday, August 20 at approximately 08:00 AM EDT

Thursday, August 21 at approximately 09:00 AM EDT

Friday, August 22 at approximately 10:00 AM EDT

Saturday, August 23 at approximately 11:00 AM EDT