Shorebirds and More at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

Photo of the Day

Are Your Eggs All They’re Cracked Up To Be?

Looks like I’m gonna be in the doghouse again—this time by way of the hen house. But why should I care? Here we go.

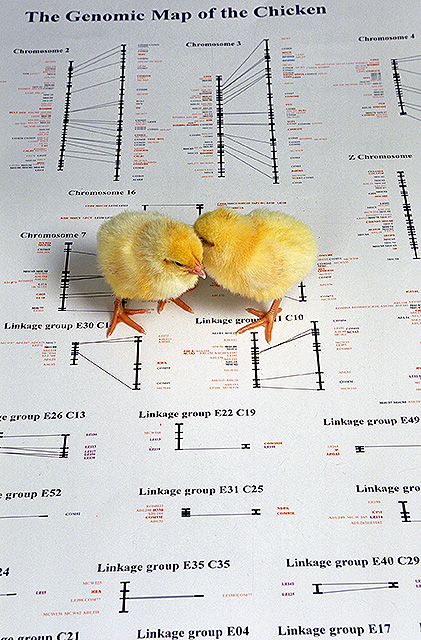

A few weeks ago, back when eggs were still selling for less than five dollars a dozen, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture renewed calls for owners and caretakers of outdoor flocks of domestic poultry (backyard chickens) to keep their birds indoors to protect them from the spread of bird flu—specifically “Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza” (H.P.A.I.). At least one story edited and broadcast by a Susquehanna valley news outlet gave the impression that “vultures and hawks” are responsible for the spread of avian flu in chickens. To see if recent history supports such a deduction, let’s have a look at the U.S.D.A.’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s 2022-2023 list of the detection of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in birds affected in counties of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed in Pennsylvania.

H.P.A.I. 2022 Confirmed Detections as of January 13, 2023

This listing includes date of detection, county of collection, type/species of bird, and number of birds affected. WOAH (World Organization for Animal Health) birds include backyard poultry, game birds raised for eventual release, domestic pet species, etc.

12/30/2022 Adams Black Vulture

12/15/2022 Lancaster Canada Goose

12/15/2022 Lebanon Black Vulture

12/15/2022 Adams Black Vulture (3)

11/8/2022 Cumberland Black Vulture (4)

11/4/2022 Dauphin WOAH Non-Poultry (130)

10/19/2022 Dauphin Captive Wild Rhea (4)

10/17/2022 Adams Commercial Turkey (15,100)

10/11/2022 Adams WOAH Poultry (2,800)

9/30/2022 Lancaster Mallard

9/30/2022 Lancaster Mallard

9/29/2022 Lancaster WOAH Non-Poultry (180)

9/29/2022 York Commercial Turkey (25,900)

8/24/2022 Dauphin Captive Wild Crane

7/15/2022 Lancaster Great Horned Owl

7/15/2022 York Bald Eagle

7/15/2022 Dauphin Bald Eagle

6/16/2022 Dauphin Black Vulture

6/16/2022 Dauphin Black Vulture (4)

5/31/2022 Lancaster Black Vulture (2)

5/31/2022 Lancaster Black Vulture

5/10/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (72,300)

4/29/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Duck (19,300)

4/27/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Broiler (18,100)

4/26/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (307,400)

4/22/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Broiler (50,300)

4/20/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (1,127,700)

4/20/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (879,400)

4/15/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (1,380,500)

In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, it’s pretty obvious that the outbreak of avian flu got its foothold inside some of the area’s big commercial poultry houses. Common sense tells us that hawks, vultures, and other birds didn’t migrate north into the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed carrying bird flu, then kick in the doors of the enclosed hen houses to infect the flocks of chickens therein. Anyone paying attention during these past three years knows that isolation and quarantine are practices more easily proposed than sustained. Human footprints are all over the introduction of this infection into these enormous flocks. Simply put, men don’t wipe their feet when no one is watching! The outbreak of bird flu in these large operations was brought under control quickly, but not until teams of state and federal experts arrived to assure proper sanitary and isolation practices were being implemented and used religiously to prevent contaminated equipment, clothing, vehicles, feed deliveries, and feet from transporting virus to unaffected facilities. Large poultry houses aren’t ideal enclosures with absolute capabilities for excluding or containing viruses and other pathogens. Exhaust systems often blow feathers and waste particulates into the air surrounding these sites and present the opportunity for flu to be transported by wind or service vehicles and other conveyances that pass through contaminated ground then move on to other sites—both commercial and non-commercial. Waste material and birds (both dead and alive) removed from commercial poultry buildings can spread contamination during transport and after deposition. The sheer volume of the potentially infected organic material involved in these large poultry operations makes absolute containment of an outbreak nearly impossible.

Looking at the timeline created by the list of U.S.D.A. detections, the opportunity for bird flu to leave the commercial poultry loop probably happened when wild birds gained access to stored or disposed waste and dead animals from an infected commercial poultry operation. For decades now, many poultry operations have dumped dead birds outside their buildings where they are consumed by carrion-eating mammals, crows, vultures, Bald Eagles, and Red-tailed Hawks. For these species, discarded livestock is one of the few remaining food sources in portions of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where high-intensity farming has eliminated other forms of sustenance. They will travel many miles and gather in unnatural concentrations to feast on these handouts—creating ideal circumstances for the spread of disease.

The sequence of events indicated by the U.S.D.A. list would lead us to infer that vultures and Bald Eagles were quick to find and consume dead birds infected with H5N1—either wild species such as waterfowl or more likely domestic poultry from commercial operations or from infectious backyard flocks that went undetected. As the report shows, Black Vultures in particular seem to be susceptible to morbidity. Their frequent occurrence as victims highlights the need to dispose of potentially infectious poultry carcasses properly—allowing no access for hungry wildlife including scavengers.

The positive test on a Great Horned Owl is an interesting case. While the owl may have consumed an infected wild bird such as a crow, there is the possibility that it consumed or contacted a mammalian scavenger that was carrying the virus. Aside from rodents and other small mammals, Great Horned Owls also prey upon Striped Skunks with some regularity. Most of the dead poultry from flu-infected commercial flocks was buried onsite in rows of above-ground mounds. Skunks sniff the ground for subterranean fare, digging up invertebrates and other food. Buried chickens at a flu disposal site would constitute a feast for these opportunistic foragers. A skunk would have no trouble at all finding at least a few edible scraps at such a site. Then a Great Horned Owl could easily seize and feed upon such a flu virus-contaminated skunk.

BACKYARD POULTRY

Before we proceed, the reader must understand the seldom-stated and never advertised mission of the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture—to protect the state’s agriculture industry. That’s it; that’s the bottom line. Regulation and enforcement of matters under the purview of the agency have their roots in this goal. While they may also protect the public health, animal health, and other niceties, the underlying purpose of their existence in its current manifestation is to protect the agriculture industry(s) as a whole.

This is not a trait unique to the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. It is at the core of many other federal and state agencies as well. Following the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle in 1906, a novel decrying “wage slavery” in the meat packing industry, the federal government took action, not for the purpose of improving the working conditions for labor, but to address the unsanitary food-handling practices described in the book by creating an inspection program to restore consumer confidence in the commercially-processed meat supply so that the industry would not crumble.

Locally, few things make the dairy industry and the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture more nervous than small producers selling “raw milk”. In the days before pasteurization and refrigeration, people were frequently sickened and some even died from drinking bacteria-contaminated “raw milk”. In Pennsylvania, the production and sale of dairy products including “raw milk” is closely regulated and requires a permit. Retention of a permit requires submitting to inspections and passing periodic herd and product testing. Despite the dangers, many consumers continue to buy “raw milk” from farms without permits. These sales are like a ticking time bomb. The bad publicity from an outbreak of food-borne illness traced back to a dairy product—even if it originated in an “outlaw” operation—could decimate sales throughout the industry. Because just one sloppy farm selling “raw milk” could instantly erode consumer confidence and cause an industry-wide collapse of the market resulting in a loss of millions of dollars in sales, it is a deeply concerning issue.

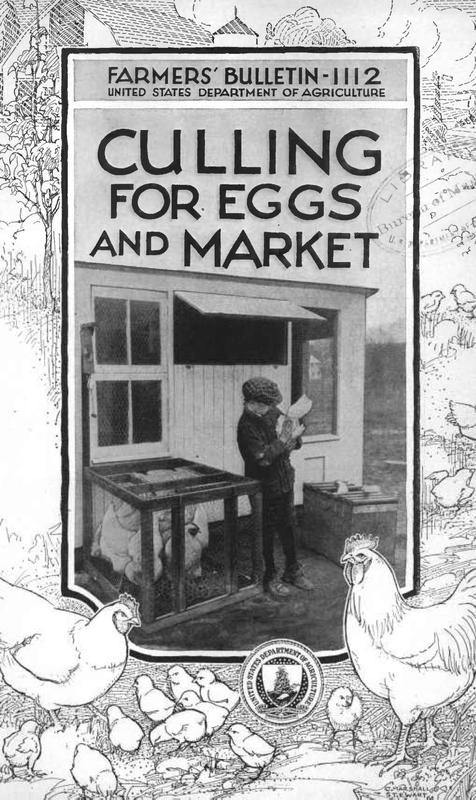

Enter the backyard chicken—a two-fold source of anxiety for the poultry industry and its regulators. Like unregulated meat and dairy products, eggs and meat from backyard poultry flocks are often marketed without being monitored for the pathogens responsible for the transmission of food-borne illness. From the viewpoint of the poultry industry, this situation poses a human health risk that in the event of an outbreak, could erode consumer confidence, not only in homegrown organic and free-range products, but in the commercial line of products as well. Consumers can be very reactive upon hearing news of an outbreak, recalling few details other than “the fowl is foul”— then refraining from buying poultry products. The second and currently most concerning source of trepidation among members of the poultry industry though is the threat of avian flu and other diseases being harbored in and transmitted via flocks of backyard birds.

The Green Revolution, the post-World War II initiative that integrated technology into agriculture to increase yields and assure an adequate food supply for the growing global population, brought changes to the way farmers raised poultry for market. Small-scale poultry husbandry slowly disappeared from many farms. Instead, commercial operations concentrated birds into progressively-larger indoor flocks to provide economy of scale. Over time, genetics and nutrition science have provided the American consumer with a line of readily available high-quality poultry products at an inexpensive price. Within these large-scale operations, poultry health is closely monitored. Though these enclosures may house hundreds of thousands of birds, the strategy during an outbreak of communicable disease is to contain an outbreak to the flock therein, writing it off so to speak to prevent the pathogens from finding their way into the remainder of the population in a geographic area, thus saving the industry at the expense of the contents of a single operation. Adherence to effective biosecurity practices can contain outbreaks in this way.

The renewed popularity of backyard poultry is a reversal of the decades-long trend towards reliance on ever-larger indoor operations for the production of birds and eggs. But backyard flocks may make less-than-ideal neighbors for commercial operations, particularly when birds are left to roam outdoors. Visitors to properties with roaming chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys may pick up contamination on their shoes, clothing, tires, and equipment, then transmit the pathogenic material to flocks at other sites they visit without ever knowing it. Even the letter carrier can carry virus from a mud puddle on an infected farm to a grazing area on a previously unaffected one. Unlike commercial operations, hobby farms frequently buy, sell, and trade livestock and eggs without regard to disease transmission. The rate of infection in these operations is always something of a mystery. No state or county permits are required for keeping small numbers of poultry and outbreaks like avian flu are seldom reported by caretakers of flocks of home-raised birds, though their occurrence among them may be widespread. The potential for pathogens like avian flu virus circulating long-term among flocks of backyard poultry in close proximity to commercial houses is a real threat to the industry.

There are a variety of motivations for tending backyard poultry. While for some it is merely a form of pet keeping, others are more serious about the practice—raising and breeding exotic varieties for show and trade. Increasingly, backyard flocks are being established by people seeking to provide their own source of eggs or meat. For those with larger home operations, supplemental income is derived from selling their surplus poultry products. Many of these backyard enthusiasts are part of a movement founded on the belief that, in comparison to commercially reared birds, their poultry is raised under healthier and more humane conditions by roaming outdoors. Organic operators believe their eggs and meat are safer for consumption—produced without the use of chemicals. For the movement’s most dedicated “true believers”, the big poultry industry is the antagonist and homegrown fowl is the only hope. It’s similar to the perspective members of the “raw milk” movement have toward pasteurized milk. True believers are often willing to risk their health and well-being for the sake of the cause, so questioning the validity of their movement can render a skeptic persona non grata.

For the consumer, the question arises, “Are eggs and poultry from the small-scale operations better?”

While many health-conscious animal-friendly consumers would agree to support the small producer from the local farm ahead of big business, the reality of supplying food for the masses requires the economy of scale. The billions of people in the world can’t be fed using small-scale and/or organic growing methods. The Green Revolution has provided record-high yields by incorporating herbicides, insecticides, plastic, and genetic modification into agriculture. To protect livestock and improve productivity, enormous indoor operations are increasingly common. Current economics tell the story—organic production can’t keep up with demand, that’s why the prices for items labelled organic are so much higher.

To the consumer, buying poultry raised outdoors is an appealing option. Compared to livestock crowded into buildings, they feel good about choosing products from small operations where birds roam free and happy in the sunshine.

But is the quality really better? Some research indicates not. Salmonella outbreaks have been traced back to poultry meat sourced from small unregulated operations. Studies have found dioxins in eggs produced by hens left to forage outdoors. The common practice of burning trash can generate a quantity of ash sufficient to contaminate soils with dioxins, chemical compounds which persist in the environment and in the fatty tissue of animals for years. The presence of elevated levels of dioxins in eggs from outdoor grazing operations may pose a potential consumer confidence liability for the entire egg industry.

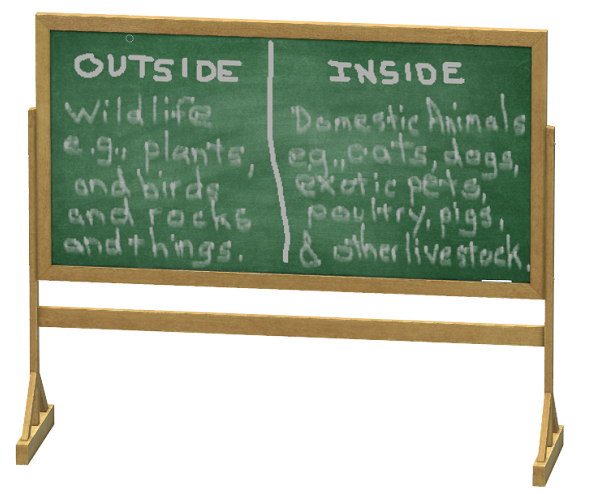

Birds raised or kept in an outdoor zoo or backyard poultry setting can be susceptible to viruses and other pathogens when wild birds including vultures and hawks become attracted to the captives’ food and water when it is placed in an accessible location. In addition, hunting and scavenging birds are opportunistic— attracted to potential food animals when they perceive vulnerability. Selective breeding under domestication has rendered food poultry fat, dumb, and too genetically impaired for survival in the wild. These weaknesses instantly arouse the curiosity of raptors and other predators whose function in the food web is to maintain a healthy population of animals at lower tiers of the food chain by selectively consuming the sickly and weak. In settings such as those created by high-intensity agriculture and urbanization, wild birds may find the potential food sources offered by outdoor zoos and backyard poultry irresistible. As a result they may perch, loaf, and linger around these locations—potentially exposing the captive birds to their droppings and transmission of bird flu and other diseases.

While outdoor poultry operations usually raise far fewer birds than their commercial counterparts, their animals are still kept in densities high enough to promote the rapid spread of microbiological diseases. Clusters of outdoor flocks can become a reservoir of pathogens with the capability of repeatedly circulating disease into populations of wild birds and even into commercial poultry operations—threatening the industry and food supply for millions of people. For this reason, state and federal agencies are encouraging operators to keep backyard poultry indoors—segregated from natural and anthropogenic disease vectors and conveyances that might otherwise visit and interact with the flock.

BACK TO THE FUTURE?—NOT LIKELY

The hobby farmer, the homesteader, the pet keeper, and the consumer seldom realize what the modern farmer is coming to know—domestic livestock must be segregated from the sources of contamination and disease that occur outdoors. Adherence to this simple concept helps assure improved health for the animals and a safer food supply for consumers. In the future, outdoor production of domestic animals, particularly those used as a food supply, is likely to be classified as an outdated and antiquated form of animal husbandry.

THE THREAT FROM PRIONS

If there are three things the world learned from the SARS CoV-2 (Covid-19) epidemic, it’s that 1) eating or handling bush meat can bring unwanted surprises, 2) dense populations of very mobile humans are ideal mediums for uncontrolled transmission of disease, and 3) quarantine is easier said than done.

If you think viruses are bad, you don’t even want to know about prions. Prions are a prime example of why now is a good time to begin housing domestic animals, including pets, indoors to segregate them from wildlife. And prions are a good example of why we really ought to think twice about relying on wild animals as a source of food. Prions may make us completely rethink the way we interact with animals of any kind—but we had better do our thinking fast because prions turn the brains of their victims into Swiss cheese.

Diseases caused by prions are rapidly progressing neurodegenerative disorders for which there is no cure. Prions are an abnormal isoform of a cellular glycoprotein. They are currently rare, but prions, because they are not living entities, possess the ability to begin accumulating in the environment. They not only remain in detritus left behind by the decaying carcasses of afflicted animals, but can also be shed in manure—entering soils and becoming more and more prevalent over time. Some are speculating that they could wind up being man’s downfall.

The Centers for Disease Control lists these human afflictions caused by prions…

-

-

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD)

- Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD)

- Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker Syndrome

- Fatal Familial Insomnia

- Kuru

-

The Centers for Disease Control lists these prion-caused ailments of other animals…

-

-

- Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE)

- Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD)

- Scrapie

- Transmissible Mink Encephalopathy

- Feline Spongiform Encephalopathy

- Ungulate Spongiform Encephalopathy

-

SOURCES

Schoeters, Greet, and Ron Hoogenboom. 2006. Contamination of Free-range Chicken Eggs with Dioxins and Dioxin-like Polychlorinated Biphenyls. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. (10):908-14.

Szczepan, Mikolajczyk, Marek Pajurek, Malgorzata Warenik-Bany, and Sebastian Maszewski. 2021. Environmental Contamination of Free-range Hen with Dioxin. Journal of Veterinary Research. 65(2):225-229.

U.S.D.A. Animal and Plant Inspection Service. 2022 Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-2022/2022-hpai-commercial-backyard-flocks as accessed January 14, 2023.

U.S.D.A. Animal and Plant Inspection Service. 2022 Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-2022/2022-hpai-wild-birds as accessed January 14, 2023.

The Gasoline and Gunpowder Gang’s Second-biggest Holiday of the Year

For members of the gasoline and gunpowder gang in Pennsylvania, the coming two weeks are the second-biggest holiday of the year. Cloaked in ceremonial orange, worshipers of the White-tailed Deity are making their annual pilgrimage into the great outdoors to beat the bushes in search of their idol. For the fortunate among the faithful, their devotion culminates in a testosterone/adrenaline-charged sacrifice of the supreme being.

Remember, emotions run high during this blood-letting festival—sometimes overwhelming secular attributes like logic and rational decision-making. You don’t want to be in the crossfire—so stay out of the woods!

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Coming Soon, Very Soon: Brood X Periodical Cicadas

Yesterday, a hike through a peaceful ridgetop woods in the Furnace Hills of southern Lebanon County resulted in an interesting discovery. It was extraordinarily quiet for a mid-April afternoon. Bird life was sparse—just a pair of nesting White-breasted Nuthatches and a drumming Hairy Woodpecker. A few deer scurried down the hillside. There was little else to see or hear. But if one were to have a look below the forest floor, they’d find out where the action is.

2021 is an emergence year for Brood X, the “Great Eastern Brood”—the largest of the 15 surviving broods of Periodical Cicadas. After seventeen years as subterranean larvae, the nymphs are presently positioned just below ground level, and they’re ready to see sunlight. After tunneling upward from the deciduous tree roots from which they fed on small amounts of sap since 2004, they’re awaiting a steady ground temperature of about 64 degrees Fahrenheit before surfacing to climb a tree, shrub, or other object and undergo one last molt into an imago—a flying adult.

The woodlots of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed won’t be quiet for long. Loud choruses of male Periodical Cicadas will soon roar through forest and verdant suburbia. They’re looking for love, and they’re gonna die trying to find it. And dozens and dozens of animal species will take advantage of the swarms to feed themselves and their young. Yep, the woods are gonna be a lively place real soon.

Piebald Deer at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area

Except for a few injured stragglers, Snow Geese have departed Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties to continue their journey north to breeding grounds in Canada. The crowds of observers are gone too. So if you’re looking for a reason to pay a visit to a much quieter refuge, here it is—especially if you’re a devoted deer worshiper.

There is at least one white deer being seen on the refuge. That’s right, a white deer. Its unusual color is really becoming conspicuous as the landscape begins turning from shades of gray to various hues of bright green.

If you go, you’ll need binoculars to pick out these uncommon deer. And remember to be very careful when parking and observing along Kleinfeltersville Road. The speeding cars and trucks there can be wickedly dangerous, so give them lots of room.

Forest vs. Woodlot

Let’s take a quiet stroll through the forest to have a look around. The spring awakening is underway and it’s a marvelous thing to behold. You may think it a bit odd, but during this walk we’re not going to spend all of our time gazing up into the trees. Instead, we’re going to investigate the happenings at ground level—life on the forest floor.

There certainly is more to a forest than the living trees. If you’re hiking through a grove of timber getting snared in a maze of prickly Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) and seeing little else but maybe a wild ungulate or two, then you’re in a has-been forest. Logging, firewood collection, fragmentation, and other man-made disturbances inside and near forests take a collective toll on their composition, eventually turning them to mere woodlots. Go enjoy the forests of the lower Susquehanna valley while you still can. And remember to do it gently; we’re losing quality as well as quantity right now—so tread softly.

Migrating North?

A steady stream of birds was on the move this morning over Conewago Falls. There were hundreds of Ring-billed Gulls, scores of Herring Gulls, and a few Great Black-backed Gulls to dominate the flight. Then too there were thirteen Mallards, Turkey Vultures and a Black Vulture, twenty or more American Robins, a half a dozen Bald Eagles (juvenile and immature birds), a couple of Red-winged Blackbirds, and, perhaps most unusual of all, a flock of a dozen Scoters (Melanitta species), a waterfowl typical of the Mid-Atlantic surf in winter. All of these birds were diligently following the river, and into a headwind no less.

“Hold on just a minute there, buster,” you may say, “I’ve looked at the migration count by dutifully clicking on the logo above and there is nothing but zeroes on the count sheet for today. The season totals have not changed since the previous count day!”

Ah-ha, my dedicated friend, correct you are. It seems that today’s bird flight was solely in one direction. And that direction was upriver, moving north into a north breeze, on a heading which conflicts with all logic for creatures that should still be headed south for winter. As a result, none of the birds observed today were counted on the “Autumn Migration Count”.

You might say, “Don’t you know that Winter Solstice was three days ago, so autumn and autumn migration is over.”

Okay, point well taken. I should therefore clarify that what we title as “Autumn Migration Count” is more accurately a census of birds, insects, and other creatures transiting from northerly latitudes to more favorable latitudes to the south for winter. This transit can begin as early as late June and extend into the first weeks of winter. While most of this movement is motivated by the reduced hours of daylight during the period, late season migrants are often responding to ice, bad weather, or lack of food to prompt a journey further south. Migration south in late December and January occurs even while the amount of daylight is increasing slightly in the days following the Winter Solstice.

So what of the birds seen flying north today? There was some snow cover that has melted away, and the ice that formed on the river a week ago is gone due to the milder than normal temperatures this week.

One may ask, “Were the birds seen today migrating north?”

Let’s look at the species seen moving upriver today a try to determine their motivation.

First, and perhaps most straight-forward, is the huge flight of gulls. Wintering gulls on the Susquehanna River near Conewago Falls tend to spend their nights in flocks on the water or on treeless islands and rocky outcrops in the river. Many hundreds, sometimes thousands, find such favorable sites along the fifteen mile stretch of river from Conewago Falls downstream to Lake Clarke and the Conejohela Flats at Washington Boro. Each morning most of these gulls venture out to suburbia, farmland, landfill, hydroelectric dams, and other sections of river in search of food. Gulls are very able fliers and easily cover dozens of miles outbound and inbound each day in search of food. Many of the gulls seen this morning were probably on their way to the Harrisburg metropolitan area to eat trash. Barring any extraordinary buildups of ice on this section of river, one would expect these gulls to remain and make these daily excursions to food sources through early spring.

Second, throughout the season Bald Eagles have been tallied on the migration count with caution. Flight altitude, behavior, plumage, and the reaction of the “local” eagles to these transients was carefully considered before counting an eagle as a migrant. They roam a lot, particularly when young, and range widely to feed. The movement of eagles up the river today was probably food related. A gathering of adult, juvenile, and immature Bald Eagles could be seen more than a half mile upstream from the migration count lookout. Those moving up the river seemed to assemble with the “locals” there throughout the morning. White-tailed Deities occasionally drown, particularly when there is thin or unstable ice on the river (as there was last week) and they attempt to tread upon it. Then, their bodies are often stranded among rocks, in trees, or on the crown of the dam. After such a mishap, their carcasses become meals for carrion-eaters in the falls. Such an unfortunate deity, or another source of food, may have been attracting the eagles in numbers today.

Next, Black and Turkey Vultures often roam widely in search of food. The small numbers seen headed up-river today would tend to mean very little when trying to determine if there is a trend or population shift. Again, food may have been luring them upriver from nearby roosts.

And finally, the scoters, Mallards, American Robins, and Red-winged Blackbirds may have been wandering as well. Toward mid-day, the wind speed picked up and the direction changed to the east. This raises the possibility that these and others of the birds seen today may sense a change in weather, and may seek to take flight from the inclement conditions. Prompted by the ocean breeze and in an attempt to avoid a storm, was there some movement away from the Atlantic Coastal Plain to the upper Piedmont today? Many species may make these types of reactive movements. Is it possible that some birds flee or avoid ever-changing storm tracks and alter there wintering locations based on jet streams, water currents, and other climatic conditions? Probably. These are interesting dynamics and something worthy of study outside the simpler methods of a migration count.

Digging In

If you visit the shores of the Susquehanna River during the warmer months of the year, there’s a pretty good probability that you’ll be taking a visitor along home with you. Not to worry, it won’t raid the icebox or change the television channels when you leave the room to get a snack. It won’t put you in the doghouse with the landlord for having a forbidden pet. As a matter of fact, you may not even notice your new companion. Sure enough though, it’s there, crawling through the luxurious warm fabric of your clothing and seeking out a good place to dig in and chow down. O.K., so now you’re worried.

Ticks, particularly the American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis), are widespread in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Like spiders, they are arachnids. They have a four-stage life cycle (egg-larva-nymph-adult) which, in the case of D. variabilis, requires a minimum of two months to complete. Females lay up to 6,500 eggs on the ground. Then the fun begins as the larvae with any hope of survival must attach to a small mammal to feed. They can survive for almost a year before finding a host. After a successful hookup and subsequent blood feast of up to two weeks duration, the larva drops to the ground, molts into a nymph, and finds another small mammal, usually a bit bigger this time, to feed upon. A nymph can survive for up to six months before needing to feed. Finding the second host, the nymph feeds for 3 to 10 days, then drops to the ground to molt into an adult. Adult American Dog Ticks can endure up to two years without feeding on a host. The adults mate and feed on larger mammals such as deer and domestic animals including, of course, dogs. After a blood meal of five days to two weeks duration, the adult female tick drops to the ground to lay eggs and initiate a new generation.

The American Dog Tick is renowned as a carrier of the Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever bacteria (Rickettsia rickettsii). The bacteria is vectored by the ticks from rodents to dogs and humans. The adult tick must be attached to the victim for a minimum of six to eight hours to transmit the pathogen. A rash spreading from the wrists and the ankles to other portions of the body begins two to fourteen days after infection.

Tularemia, caused by the bacteria Francisella tularensis, can be passed by the American Dog Tick. Symptoms can appear in three to twenty-one days and include chills, fever, and inflammation of the lymph nodes.

American Dog Ticks which attach to dogs, particularly near the neck, and are left in place to feed and engorge themselves for longer than five days can cause Canine Tick Paralysis. Symptoms usually begin to subside only after a recovery period following removal of the arachnid.

The American Dog Tick is exposed to Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria responsible for Lyme Disease, however, transmittal of this pathogen is by the smaller Deer Tick (Ixodes scapularis), also known as the Black-legged Tick. The Deer Tick is not presently common at Conewago Falls. In the adjacent uplands, it is widespread and is carrying Lyme Disease where the White-tailed Deity (Odocoileus virginianus), the preferred host for the ticks, is found along with mice and other small rodents, the source of B. burgdorferi bacteria. The Deer Tick easily escapes notice and cases of Lyme Disease are frequent, so vigilance is necessary.

SOURCES

Chan, Wai-Han, and Kaufman, Phillip. 2008. American Dog Tick. University of Florida Featured Creatures website entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/urban/medical/american_dog_tick.htm as accessed July 30, 2017.