Blue Tuesday

We’ve got the summertime blues for you, right here at susquehannawildlife.net…

…so don’t let the summertime blues get you down. Grab a pair of binoculars and/or a camera and go for a stroll!

Shorebirds and More at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

A Limpkin’s Journey to Pennsylvania: A Waffle House Serving Escargot at Every Exit

Mid-summer can be a less than exciting time for those who like to observe wild birds. The songs of spring gradually grow silent as young birds leave the nest and preoccupy their parents with the chore of gathering enough food to satisfy their ballooning appetites. To avoid predators, roving families of many species remain hidden and as inconspicuous as possible while the young birds learn how to find food and handle the dangers of the world.

But all is not lost. There are two opportunities for seeing unique birds during the hot and humid days of July.

First, many shorebirds such as sandpipers, plovers, dowitchers, and godwits begin moving south from breeding grounds in Canada. That’s right, fall migration starts during the first days of summer, right where spring migration left off. The earliest arrivals are primarily birds that for one reason on another (age, weather, food availability) did not nest this year. These individuals will be followed by birds that completed their breeding cycles early or experienced nest failures. Finally, adults and juveniles from successful nests are on their way to the wintering grounds, extending the movement into the months we more traditionally start to associate with fall migration—late August into October.

For those of you who find identifying shorebirds more of a labor than a pleasure, I get it. For you, July can bring a special treat—post-breeding wanderers. Post-breeding wanderers are birds we find roaming in directions other than south during the summer months, after the nesting cycle is complete. This behavior is known as “post-breeding dispersal”. Even though we often have no way of telling for sure that a wandering bird did indeed begin its roving journey after either being a parent or a fledgling during the preceding nesting season, the term post-breeding wanderer still applies. It’s a title based more on a bird sighting and it’s time and place than upon the life cycle of the bird(s) being observed. Post-breeding wanderers are often southern species that show up hundreds of miles outside there usual range, sometimes traveling in groups and lingering in an adopted area until the cooler weather of fall finally prompts them to go back home. Many are birds associated with aquatic habitats such as shores, marshes, and rivers, so water levels and their impact on the birds’ food supplies within their home range may be the motivation for some of these movements. What makes post-breeding wanderers a favorite among many birders is their pop. They are often some of our largest, most colorful, or most sought-after species. Birds such as herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, stilts, avocets, terns, and raptors are showy and attract a crowd.

While it’s often impossible to predict exactly which species, if any, will disperse from their typical breeding range in a significant way during a given year, some seem to roam with regularity. Perhaps the most consistent and certainly the earliest post-breeding wanderer to visit our region is the “Florida Bald Eagle”. Bald Eagles nest in “The Sunshine State” beginning in the fall, so by early spring, many of their young are on their own. By mid-spring, many of these eagles begin cruising north, some passing into the lower Susquehanna valley and beyond. Gatherings of dozens of adult Bald Eagles at Conowingo Dam during April and May, while our local adults are nesting and after the wintering birds have gone north, probably include numerous post-breeding wanderers from Florida and other Gulf Coast States.

So this week, what exactly was it that prompted hundreds of birders to travel to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area from all over the Mid-Atlantic States and from as far away as Colorado?

Was it the majestic Great Blue Herons and playful Killdeer?

Was it the colorful Green Herons?

Was it the Great Egrets snapping small fish from the shallows?

Was it the small flocks of shorebirds like these Least Sandpipers beginning to trickle south from Canada?

All very nice, but not the inspiration for traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles to see a bird.

It was the appearance of this very rare post-breeding wanderer…

…Pennsylvania’s first record of a Limpkin, a tropical wading bird native to Florida, the Caribbean Islands, and South America. Many observers visiting Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area had never seen one before, so if they happen to be a “lister”, a birder who keeps a tally of the wild bird species they’ve seen, this Limpkin was a “lifer”.

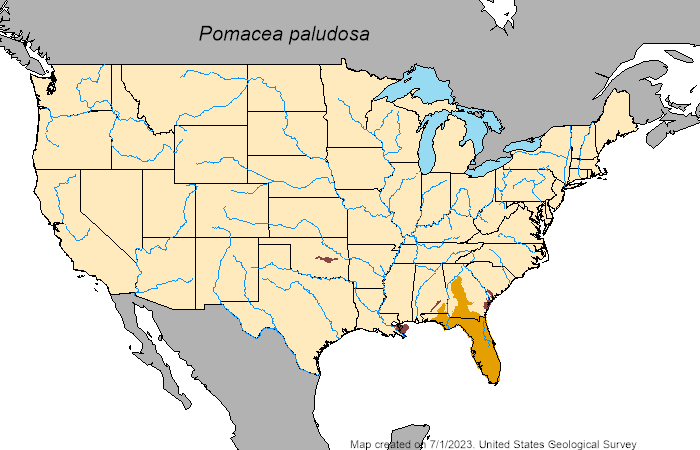

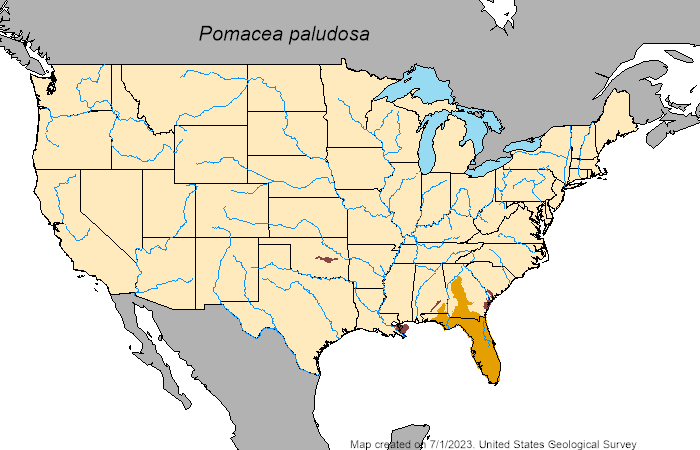

The Limpkin is an inhabitant of vegetated marshlands where it feeds almost exclusively upon large snails of the family Ampullariidae, including the Florida Applesnail (Pomacea paludosa), the largest native freshwater snail in the United States.

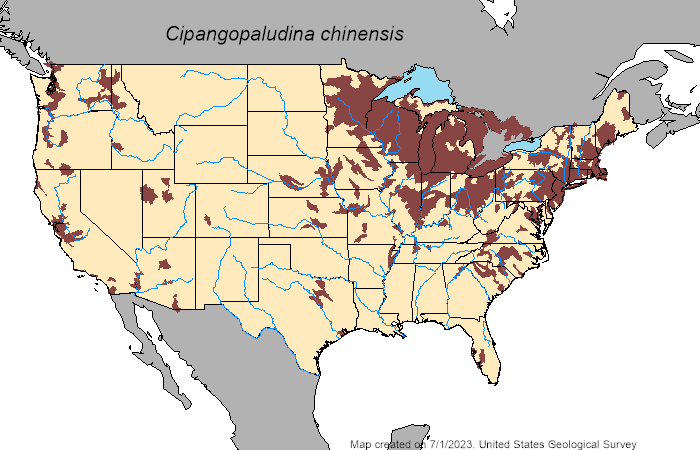

Observations of the Limpkin lingering at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area have revealed a pair of interesting facts. First, in the absence of Florida Applesnails, this particular Limpkin has found a substitute food source, the non-native Chinese Mystery Snail (Cipangopaludina chinensis). And second, Chinese Mystery Snails have recently become established in the lakes, pools, and ponds at the refuge, very likely arriving as stowaways on Spatterdock (Nuphar advena) and/or American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea), native transplants brought in during recent years to improve wetland habitat and process the abundance of nutrients (including waterfowl waste) in the water.

The Middle Creek Limpkin’s affinity for Chinese Mystery Snails may help explain how it was able to find its way to Pennsylvania in apparent good health. Look again at the map showing the range of the Limpkin’s primary native food source, the Florida Applesnail. Note that there are established populations (shown in brown) where these snails were introduced along the northern coast of Georgia and southern coast of South Carolina…

…now look at the latest U.S.G.S. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species map showing the ranges (in brown) of established populations of non-native Chinese Mystery Snails…

…and now imagine that you’re a happy-go-lucky Limpkin working your way up the Atlantic Coastal Plain toward Pennsylvania and taking advantage of the abundance of food and sunshine that summer brings to the northern latitudes. It’s a new frontier. Introduced populations of Chinese Mystery Snails are like having a Waffle House serving escargot at every exit along the way!

Be sure to click the “Freshwater Snails” tab at the top of this page to learn more about the Chinese Mystery Snail and its arrival in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Once there, you’ll find some additional commentary about the Limpkin and the likelihood of Everglade Snail Kites taking advantage of the presence of Chinese Mystery Snails to wander north. Be certain to check it out.

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Conowingo Dam: Cormorants, Eagles, Snakeheads and a Run of Hickory Shad

Meet the Double-crested Cormorant, a strangely handsome bird with a special talent for catching fish. You see, cormorants are superb swimmers when under water—using their webbed feet to propel and maneuver themselves with exceptional speed in pursuit of prey.

Double-crested Cormorants, hundreds of them, are presently gathered along with several other species of piscivorous (fish-eating) birds on the lower Susquehanna River below Conowingo Dam near Rising Sun, Maryland. Fish are coming up the river and these birds are taking advantage of their concentrations on the downstream side of the impoundment to provide food to fuel their migration or, in some cases, to feed their young.

In addition to the birds, the movements of fish attract larger fish, and even larger fishermen.

The excitement starts when the sirens start to wail and the red lights begin flashing. Yes friends, it’s showtime.

Within minutes of the renewed flow, birds are catching fish.

Then the anglers along the wave-washed shoreline began catching fish too.

The arrival of migrating Hickory Shad heralds the start of a movement that will soon include White Perch, anadromous American Shad, and dozens of other fish species that swim upstream during the springtime. Do visit Fisherman’s Park at Conowingo Dam to see this spectacle before it’s gone. The fish and birds have no time to waste, they’ll soon be moving on.

To reach Exelon’s Conowingo Fisherman’s Park from Rising Sun, Maryland, follow U.S. Route 1 south across the Conowingo Dam, then turn left onto Shuresville Road, then make a sharp left onto Shureslanding Road. Drive down the hill to the parking area along the river. The park’s address is 2569 Shureslanding Road, Darlington, Maryland.

A water release schedule for the Conowingo Dam can be obtained by calling Exelon Energy’s Conowingo Generation Hotline at 888-457-4076. The recording is updated daily at 5 P.M. to provide information for the following day.

And remember, the park can get crowded during the weekends, so consider a weekday visit.

Fire and Ice at Conewago Falls

This morning, the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed experienced remotely the effects of fire and ice.

At daybreak, the cold air mass that brought the first freeze of the season to northernmost New England gave us a taste of the cold with temperatures below 50 degrees throughout.

At sunrise, the cloudless sky had a peculiar overcast look with no warm glow on buildings, vegetation, and terrain. Soon, the sun was well above the horizon, yet there was still a sort of darkness across the landscape.

All that bright filtered sunlight was ideal for photographing butterflies along the Conewago Falls shoreline. Have a look.

Summer Breeze

A moderate breeze from the south placed a headwind into the face of migrants trying to wing their way to winter quarters. The urge to reach their destination overwhelmed any inclination a bird or insect may have had to stay put and try again another day.

Blue Jays were joined by increasing numbers of American Robins crossing the river in small groups to continue their migratory voyages. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and a handful of sandpipers headed down the river route. Other migrants today included a Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis), and a few Common Mergansers (Mergus merganser), House Finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), and Common Grackles (Quiscalus quiscula).

The afternoon belonged to the insects. The warm wind blew scores of Monarchs toward the north as they persistently flapped on a southwest heading. Many may have actually lost ground today. Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) and Cloudless Sulphur butterflies were observed battling their way south as well. All three of the common migrating dragonflies were seen: Common Green Darner (Anax junius), Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens), and Black Saddlebags (Tramea lacerata).

The warm weather and summer breeze are expected to continue as the rain and wind from Hurricane Nate, today striking coastal Alabama and Mississippi, progresses toward the Susquehanna River watershed during the coming forty-eight hours.

Blue Jay Way

The Neotropical birds that raised their young in Canada and in the northern United States have now logged many miles on their journey to warmer climates for the coming winter. As their density decreases among the masses of migrating birds, a shift to species with a tolerance for the cooler winter weather of the temperate regions will be evident.

Though it is unusually warm for this late in September, the movement of diurnal migrants continues. This morning at Conewago Falls, five Broad-winged Hawks (Buteo platypterus) lifted from the forested hills to the east, then crossed the river to continue a excursion to the southwest which will eventually lead them and thousands of others that passed through Pennsylvania this week to wintering habitat in South America. Broad-winged Hawks often gather in large migrating groups which swarm in the rising air of thermal updrafts, then, after gaining substantial altitude, glide away to continue their trip. These ever-growing assemblages from all over eastern North America funnel into coastal Texas where they make a turn to south around the Gulf of Mexico, then continue on toward the tropics. In the coming weeks, a migration count at Corpus Christi in Texas could tally 100,000 or more Broad-winged Hawks in a single day as a large portion of the continental population passes by. You can track their movement and that of other diurnal raptors as recorded at sites located all over North America by visiting hawkcount.org on the internet. Check it out. You’ll be glad you did.

Nearly all of the other migrants seen today have a much shorter flight ahead of them. Red-bellied Woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus), Red-headed Woodpeckers (Melanerpes erythrocephalus), and Northern Flickers (Colaptes auratus) were on the move. Migrating American Robins (Turdus migratorius) crossed the river early in the day, possibly leftovers from an overnight flight of this primarily nocturnal migrant. The season’s first Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) arrived. American Goldfinches are easily detected by their calls as they pass overhead. Look carefully at the goldfinches visiting your feeder, the birds of summer are probably gone and are being replaced by migrants currently passing through.

By far, the most conspicuous migrant today was the Blue Jay. Hundreds were seen as they filtered out of the hardwood forests of the diabase ridge to cautiously cross the river and continue to the southwest. Groups of five to fifty birds would noisily congregate in trees along the river’s edge, then begin flying across the falls. Many wary jays abandoned their small crossing parties and turned back. Soon, they would try the trip again in a larger flock.

A look at this morning’s count reveals few Neotropical migrants. With the exception of the Broad-winged Hawks and warblers, the migratory species seen today will winter in a sub-tropical temperate climate, primarily in the southern United States, but often as far north as the lower Susquehanna River valley. The individual birds observed today will mostly continue to a winter home a bit further south. Those that will winter in the area of Conewago Falls will arrive in October and later.

The long-distance migrating insect so beloved among butterfly enthusiasts shows signs of improving numbers. Today, more than two dozen Monarchs were seen crossing the falls and slowly flapping and gliding their way to Mexico.