Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Only fools mess around with bees, wasps, and hornets as they collect nectar and go about their business while visiting flowering plants. Relentlessly curious predators and other trouble makers quickly learn that patterns of white, yellow, or orange contrasting with black are a warning that the pain and anguish of being zapped with a venomous sting awaits those who throw caution to the wind. Through the process of natural selection, many venomous and poisonous animals have developed conspicuously bright or contrasting color schemes to deter would-be predators and molesters from making such a big mistake.

Visual warnings enhance the effectiveness of the defensive measures possessed by venomous, poisonous, and distasteful creatures. Aggressors learn to associate the presence of these color patterns with the experience of pain and discomfort. Thereafter, they keep their distance to avoid any trouble. In return, the potential victims of this unsolicited aggression escape injury and retain their defenses for use against yet-to-be-enlightened pursuers. Thanks to their threatening appearance, the chances of survival are increased for these would-be victims without the need to risk death or injury while deploying their venomous stingers, poisonous compounds, or other defensive measures.

One shouldn’t be surprised to learn that over time, as these aforementioned venomous, poisonous, and foul-tasting critters developed their patterns of warning colors, there were numerous harmless animals living within close association with these species that, through the process of natural selection, acquired nearly identical color patterns for their own protection from predators. This form of defensive impersonation is known as Batesian mimicry.

Let’s take a look at some examples of Batesian mimicry right here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Suppose for a moment that you were a fly. As you might expect, you would have plenty to fear while you spend your day visiting flowers in search of energy-rich nectar—hundreds of hungry birds and other animals want to eat you.

If you were a fly and you were headed out and about to call upon numerous nectar-producing flowers so you could round up some sweet treats, wouldn’t you feel a whole lot safer if you looked like those venomous bees, wasps, and hornets in your neighborhood? Wouldn’t it be a whole lot more fun to look scary—so scary that would-be aggressors fear that you might sting them if they gave you any trouble?

Suppose Mother Nature and Father Time dressed you up to look like a bee or a wasp instead of a helpless fly? Then maybe you could go out and collect sweets without always worrying about the bullies and the brutes, just like these flies of the lower Susquehanna do…

FLOWER FLIES/HOVER FLIES

TACHINID FLIES

BEE FLIES

So let’s review. If you’re a poor defenseless fly and you want to get your fair share of sweets without being gobbled up by the beasts, then you’ve got to masquerade like a strongly armed member of a social colony—like a bee, wasp, or hornet. Now look scary and go get your treats. HAPPY HALLOWEEN!

What’s all this buzz about bees? And what’s a hymanopteran? Well, let’s see.

Hymanoptera—our bees, wasps, hornets and ants—are generally considered to be our most evolved insects. Some form complex social colonies. Others lead solitary lives. Many are essential pollinators of flowering plants, including cultivars that provide food for people around the world. There are those with stingers for disabling prey and defending themselves and their nests. And then there are those without stingers. The predatory species are frequently regarded to be the most significant biological controls of the insects that might otherwise become destructive pests. The vast majority of the Hymanoptera show no aggression toward humans, a demeanor that is seldom reciprocated.

Late summer and early autumn is a critical time for the Hymanoptera. Most species are at their peak of abundance during this time of year, but many of the adult insects face certain death with the coming of freezing weather. Those that will perish are busy, either individually or as members of a colony, creating shelter and gathering food to nourish the larvae that will repopulate the environs with a new generation of adults next year. Without abundant sources of protein and carbohydrates, these efforts can quickly fail. Protein is stored for use by the larval insects upon hatching from their eggs. Because the eggs are typically deposited in a cell directly upon the cache of protein, the larvae can begin feeding and growing immediately. To provide energy for collecting protein and nesting materials, and in some cases excavating nest chambers, Hymanoptera seek out sources of carbohydrates. Species that remain active during cold weather must store up enough of a carbohydrate reserve to make it through the winter. Honey Bees make honey for this purpose. As you are about to see, members of this suborder rely predominately upon pollen or insect prey for protein, and upon nectar and/or honeydew for carbohydrates.

We’ve assembled here a collection of images and some short commentary describing nearly two dozen kinds of Hymanoptera found in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the majority photographed as they busily collected provisions during recent weeks. Let’s see what some of these fascinating hymanopterans are up to…

SOLITARY WASPS

CUCKOO WASPS

SWEAT BEES

LEAFCUTTER AND MASON BEES

BUMBLE BEES, CARPENTER BEES, HONEY BEES, AND DIGGER BEES

SCOLIID WASPS

PAPER WASPS

YELLOWJACKETS AND HORNETS

POTTER WASPS

ANTS

We hope this brief but fascinating look at some of our more common bees, wasps, hornets, and ants has provided the reader with an appreciation for the complexity with which their food webs and ecology have developed over time. It should be no great mystery why bees and other insects, particularly native species, are becoming scarce or absent in areas of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where the landscape is paved, hyper-cultivated, sprayed, mowed, and devoid of native vegetation, particularly nectar-producing plants. Late-summer and autumn can be an especially difficult time for hymanopterans seeking the sources of proteins and carbohydrates needed to complete preparations for next year’s generations of these valuable insects. An absence of these staples during this critical time of year quickly diminishes the diversity of species and begins to tear at the fabric of the food web. This degradation of a regional ecosystem can have unforeseen impacts that become increasingly widespread and in many cases permanent.

Editor’s Note: No bees, wasp, hornets, or ants were harmed during this production. Neither was the editor swarmed, attacked, or stung. Remember, don’t panic, just observe.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

(If you’re interested in insects, get this book!)

Grasshoppers are perhaps best known for the occasions throughout history when an enormous congregation of these insects—a “plague of locusts”—would assemble and rove a region to feed. These swarms, which sometimes covered tens of thousands of square miles or more, often decimated crops, darkened the sky, and, on occasion, resulted in catastrophic famine among human settlements in various parts of the world.

The largest “plague of locusts” in the United States occurred during the mid-1870s in the Great Plains. The Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus), a grasshopper of prairies in the American west, had a range that extended east into New England, possibly settling there on lands cleared for farming. Rocky Mountain Locusts, aside from their native habitat on grasslands, apparently thrived on fields planted with warm-season crops. Like most grasshoppers, they fed and developed most vigorously during periods of dry, hot weather. With plenty of vegetative matter to consume during periods of scorching temperatures, the stage was set for populations of these insects to explode in agricultural areas, then take wing in search of more forage. Plagues struck parts of northern New England as early as the mid-1700s and were numerous in various states in the Great Plains through the middle of the 1800s. The big ones hit between 1873 and 1877 when swarms numbering as many as trillions of grasshoppers did $200 million in crop damage and caused a famine so severe that many farmers abandoned the westward migration. To prevent recurrent outbreaks of locust plagues and famine, experts suggested planting more cool-season grains like winter wheat, a crop which could mature and be harvested before the grasshoppers had a chance to cause any significant damage. In the years that followed, and as prairies gave way to the expansive agricultural lands that presently cover most of the Rocky Mountain Locust’s former range, the grasshopper began to disappear. By the early years of the twentieth century, the species was extinct. No one was quite certain why, and the precise cause is still a topic of debate to this day. Conversion of nearly all of its native habitat to cropland and grazing acreage seems to be the most likely culprit.

In the Mid-Atlantic States, the mosaic of the landscape—farmland interspersed with a mix of forest and disturbed urban/suburban lots—prevents grasshoppers from reaching the densities from which swarms arise. In the years since the implementation of “Green Revolution” farming practices, numbers of grasshoppers in our region have declined. Systemic insecticides including neonicotinoids keep grasshoppers and other insects from munching on warm-season crops like corn and soybeans. And herbicides including 2,4-D (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) have, in effect, become the equivalent of insecticides, eliminating broadleaf food plants from the pasturelands and hayfields where grasshoppers once fed and reproduced in abundance. As a result, few of the approximately three dozen species of grasshoppers with ranges that include the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are common here. Those that still thrive are largely adapted to roadsides, waste ground, and small clearings where native and some non-native plants make up their diet.

Here’s a look at four species of grasshoppers you’re likely to find in disturbed habitats throughout our region. Each remains common in relatively pesticide-free spaces with stands of dense grasses and broadleaf plants nearby.

CAROLINA GRASSHOPPER

Dissosteira carolina

DIFFERENTIAL GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus differentialis

TWO-STRIPED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus bivittatus

RED-LEGGED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus femurrubrum

Protein-rich grasshoppers are an important late-summer, early-fall food source for birds. The absence of these insects has forced many species of breeding birds to abandon farmland or, in some cases, disappear altogether.

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

If you’re like us, you’re forgoing this year’s egg hunt due to the prices, and, well, because you’re a little bit too old for such a thing.

Instead, we took a closer look at some of our wildlife photographs from earlier in the week. We’ve learned from experience that we don’t always see the finer details through the viewfinder, so it often pays to give each shot a second glance on a full-size screen. Here are a few of our images that contained some hidden surprises.

..but upon closer inspection we located…

..but after zooming in a little closer we found…

..but then, following further examination, we discovered…

THE BAD EGG

…but a careful search of the flock revealed…

Here’s wishing you and yours a Happy Halloween. It’s a much-anticipated day of excitement capped by surprise visits from strange-looking hideous creatures you’ve never seen before. They don’t stop by for a chat. Nope, not a word. Just a little bit of nearly imperceptible buzzing when the move around. You see, the little sneaks have hatched a plan. They want to eat your stuff and maybe trash the place before they go. And when you finally get rid of them, more start showing up—dozens and dozens, then hundreds. The more you have, the more you attract. You’ll be shocked that there are that many living in your neighborhood. It’s like a scene from “Nightmare on Maple Street”. The invasion drives some people mad, but you’re just going to love it. So, get ready, because here they come. Trick or Treat!

Once upon a time, a great panic spread throughout the lower Susquehanna region. A destructive mob of invaders was overtaking our verdant land and was sure to decimate all in its path. Clad in gray and butternut, they came by the thousands. Flashing their crimson banners, they signaled their arrival at each new waypoint along their route. The Pennsylvania government called upon the populace to heed the call and turn out in defense of the state. Small bands of well-intentioned citizens tried in vain to turn back the progress of the hostiles—none succeeded. But for a cadre of civic-minded elites and some small groups of college professors and their students, few responded to a call to confine the invasion along designated lines of containment. Word spread quickly throughout the valley that farms had been overrun by waves of the merciless intruders. Agrarians reported that their orchards had been stripped; they had lost all of the fruits of their labor. Stories exaggerating the hideous appearance of the approaching aliens struck fear into the faint-of-heart. The growing sentiment among the terror-stricken residents: this horde must be stopped before pestilence is visited upon everyone in the state!

And so, on the evening of June 28, 1863, just three days before the Battle of Gettysburg, the wooden Susquehanna River bridge at Columbia-Wrightsville was set ablaze just as Brigadier General John B. Gordon’s brigade of the invading Army of Northern Virginia approached the span’s west entrance preparing to cross to the eastern shore. Thus, the rebel tide was turned away from the Susquehanna at the point some contend to be the authentic “High-water Mark of the Confederacy”.

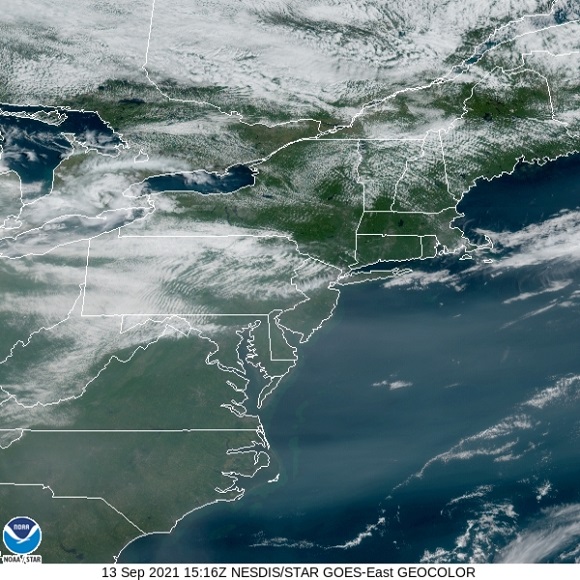

During the coming two weeks, peak numbers of migrating Neotropical birds will be passing through the northeastern United States including the lower Susquehanna valley. Hawk watches are staffed and observers are awaiting big flights of Broad-winged Hawks—hoping to see a thousand birds or more in a single day.

Broad-winged hawks feed on rodents, amphibians, and a variety of large insects while on their breeding grounds in the forests of the northern United States and Canada. They depart early, journeying to wintering areas in Central and South America before frost robs them of a reliable food supply.

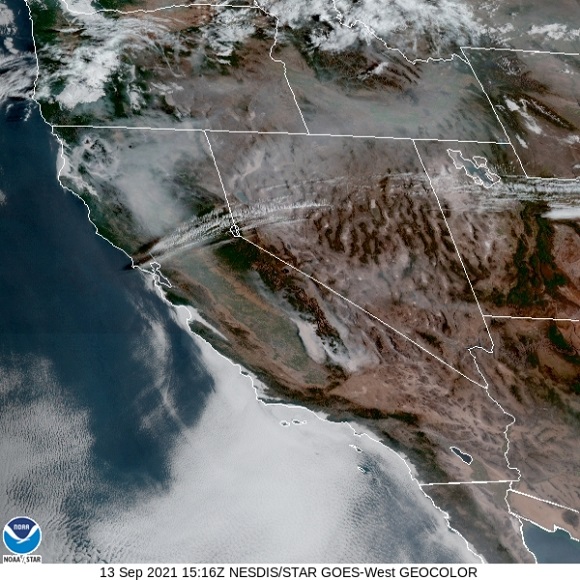

While migrating, Broad-winged Hawks climb to great altitudes on thermal updrafts and are notoriously difficult to see from ground level. Bright sunny skies with no clouds to serve as a backdrop further complicate a hawk counter’s ability to spot passing birds. Throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the coming week promises to be especially challenging for those trying to observe and census the passage of high-flying Broad-winged Hawks. The forecast of hot and humid weather is not so unusual, but the addition of smoke from fires in the western states promises to intensify the haze and create an especially irritating glare for those searching the skies for raptors.

It may seem gloomy for the mid-September flights in 2021, but hawk watchers are hardy types. They know that the birds won’t wait. So if you want to see migrating “Broad-wings” and other species, you’ve got to get out there and look up while they’re passing through.

These hawk watches in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are currently staffed by official counters and all welcome visitors:

—or you can just keep an eye on the sky from wherever you happen to be. And don’t forget to check the trees and shrubs because warbler numbers are peaking too! During recent days…

Common sense tells us that Brood X Periodical Cicada emergence begins in the southern part of the population zone, where the ground temperatures reach 64° first, then progresses to the north as the weather warms. In the forested hills where the lower Piedmont falls away onto the flat landscape of the Atlantic Coastal Plain in Maryland’s Cecil and Harford Counties, the hum of seventeen-year-old insects saturates a listener’s ears from all directions—the climax nears.

With all that food flying around, you just knew something unusual was going to show up to eat it. It’s a buffet. It’s a smorgasbord. It’s free, it’s all-you-can-eat, and it seems, at least for the moment, like it’s going to last forever. You know it’ll draw a crowd.

The Mississippi Kite (Ictinia mississippiensis), a trim long-winged bird of prey, is a Neotropical migrant, an insect-eating friend of the farmer, and, as the name “kite” suggests, a buoyant flier. It experiences no winter—breeding in the southern United States from April to July, then heading to South America for the remainder of the year. Its diet consists mostly of large flying insects including beetles, leafhoppers, grasshoppers, dragonflies, and, you guessed it, cicadas. Mississippi Kites frequently hunt in groups—usually catching and devouring their food while on the wing. Pairs nest in woodlands, swamps, and in urban areas with ample prey. They are well known for harmlessly swooping at people who happen to get too close to their nest.

Mississippi Kites nest regularly as far north as southernmost Virginia. For at least three decades now, non-breeding second-year birds known as immatures have been noted as wanderers in the Mid-Atlantic States, particularly in late May and early June. They are seen annually at Cape May, New Jersey. They are rare, but usually seen at least once every year, along the Piedmont-Atlantic Coastal Plain border in northern Delaware, northeastern Maryland, and/or southeastern Pennsylvania. Then came the Brood X Periodical Cicadas of 2021.

During the last week of May and these first days of June, there have been dozens of sightings of cicada-eating Mississippi Kites in locations along the lower Piedmont slope in Harford and Cecil Counties in Maryland, at “Bucktoe Creek Preserve” in southern Chester County, Pennsylvania, and in and near Newark in New Castle County, Delaware. They are being seen daily right on the lower Susquehanna watershed’s doorstep.

Today, we journeyed just south of Mason’s and Dixon’s Delaware-Maryland-Pennsylvania triangle to White Clay Creek State Park along Route 896 north of Newark, Delaware. Once there, we took a short bicycle ride into a wooded neighborhood across the street in Maryland to search for the Mississippi Kites that have been reported there in recent days.

Will groups of Mississippi Kites develop a taste for our seventeen-year cicadas and move north into the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed? Ah, to be young and a nomad—that’s the life. Wandering on a whim with one goal in mind—food. It could very well be that now’s the time to be on the lookout for Mississippi Kites, especially where Brood X Periodical Cicadas are abundant.

The emergence of Brood X Periodical Cicadas is now in full swing. If you visit a forested area, you may hear the distant drone of very large concentrations of one or more of the three species that make up the Brood X event. The increasing volume of a chorus tends to attract exponentially greater numbers of male cicadas from within an expanding radius, causing a swarm to grow larger and louder—attracting more and more females to the breeding site.

Each Periodical Cicada species has a distinctive song. This song concentrates males of the same species at breeding sites—then draws in an abundance of females of the same species to complete the mating process. Large gatherings of Periodical Cicadas can include all three species, but a close look at swarms on State Game Lands 145 in Lebanon County and State Game Lands 46 (Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area) in Lancaster County during recent days found marked separation by two of the three. Most swarms were dominated by Magicicada septendecim, the largest, most widespread, and most common species. However, nearly mono-specific swarms of M. cassinii, the second most numerous species, were found as well. An exceptionally large one was northwest of the village of Colebrook on State Game Lands 145. It was isolated by a tenth of a mile or more from numerous large gatherings of M. septendecim cicadas in the vicinity. These M. cassinii cicadas, with a chorus so loud that it outdistanced the songs made by the nearby swarms of M. septendecim, seized the opportunity to separate both audibly and physically from the more dominant species, thus providing better likelihood of maximizing their breeding success.

The process of identifying Periodical Cicadas is best begun by listening to their choruses, songs, and calls. After all, the sounds of cicadas will lead one to the locations where they are most abundant. The two most common species, M. septendecim and M. cassinii, produce a buzzy chorus that, when consisting of hundreds or thousands of cicadas “singing” in unison, creates a droning wail that can carry for a quarter of a mile or more. It’s a surreal humming sound that may remind one of a space ship from a science fiction film.

Listen to the songs of individual cicadas at close range and you’ll hear a difference between the widespread M. septendecim “Pharaoh Periodical Cicada” and the other two species. M. septendecim‘s song is often characterized as a drawn out version of the word “Pharaoh”, hence the species’ unofficial common name. As part of their courtship ritual, “Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas” sometimes make a purring or cooing sound, which is often extended to sound like kee-ow, then sometimes revved up further to pha-raoh. M. cassinii, often known as “Cassin’s Periodical Cicada”, and the least common species, M. septendecula, often make scratchy clicking or rattling calls as a lead-in to their song. Most observers will find little difficulty locating the widespread M. septendecim “Pharaoh Periodical Cicada” by sound, so listening for something different—the clicking call—is an easy way to zero in on the two less common species.

To penetrate the droning choruses of large numbers of “Pharaoh” and/or “Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas”, sparingly distributed M. septendecula cicadas have a noise-penetrating song consisting of a series of quick raspy notes with a staccato rhythm reminiscent of a pulsating lawn sprinkler. It can often be differentiated by a listener even in the presence of a roaring chorus of one or both of the commoner species. However, a word of caution is due. To call in others of their kind, “Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas” can produce a courtship song similar to that of M. septendecula so that they too can penetrate the choruses of the enormous numbers of “Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas” that concentrate in many areas. To play it safe, it’s best to have a good look at the cicadas you’re trying to identify.

Visually identifying Brood X Periodical Cicadas to the species level is best done by looking for two key field marks—first, the presence or absence of orange between the eye and the root of the wings, and second, the presence or absence of orange bands on the underside of the abdomen. Seeing these field marks clearly requires in-hand examination of the cicada in question.

To reliably separate Brood X Periodical Cicadas by species, it is necessary to get a closeup view of the section of the thorax between the eye and the root (insertion) of the wings, plus a look at the underside of the abdomen. Here’s what you’ll see…

Magicicada septendecim—“Pharaoh Periodical Cicada”

Magicicada cassinii—“Cassin’s Periodical Cicada”

Magicicada septendecula

There you have it. Get out and take a closer look at the Brood X Periodical Cicadas near you.

The Magi have arrived. Emanating from the shadows of a nearby forest, you may hear the endless drone of what sounds like an extraterrestrial craft. Then you get your first look at those beady red eyes set against a full suit of black armor—out of this world. The Magicicada are here at last.

If you go out and about to observe Periodical Cicadas, keep an eye open for these species too…

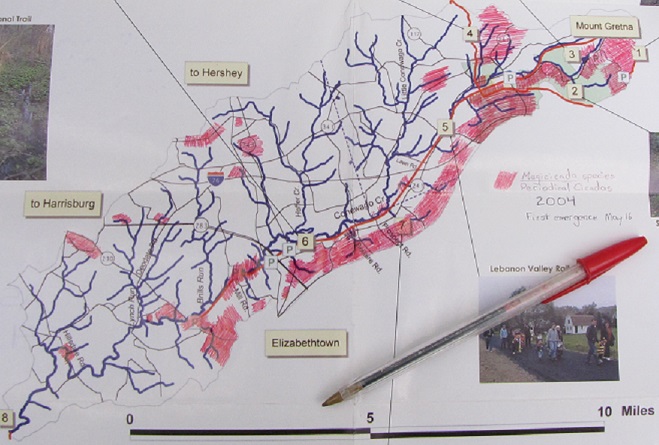

Back in the spring of 2004, members of the Tri-County Conewago Creek Association (T.C.C.C.A.), a non-profit conservation group founded to improve water quality in Conewago Creek and its tributaries in Dauphin, Lancaster, and Lebanon Counties in Pennsylvania, were, in order to better understand the status of the flora and fauna in the watershed, frequently spending their weekends surveying the animal and plant life found in the drainage basin’s forests, streams, and farmlands. This effort identified populations of several species of concern and helped supplement the more formal assessment that was used to determine the placement, scale, and scope of projects needed to reduce nutrient and erosion impairment in the Conewago’s waterways.

These regular outings happened to coincide with the Brood X Periodical Cicada emergence of 2004. Back then, as the record keeper for the T.C.C.C.A.’s weekly survey forays, your editor decided to shade a map of the Conewago Creek Watershed showing where the group’s volunteers encountered choruses of the Brood X cicadas. Fortunately, the map is still in the editor’s pile of stuff, and is reproduced here for you.

A notation on the map (visible just above the cap on the pen) indicates May 16 as the emergence date for the cicadas in 2004—seventeen years ago today.

So why no seventeen-year cicadas yet in 2021? The answer is ground temperature. This year, by mid-April, Brood X Periodical Cicadas were just below the leaves and rocks, ready to break the surface. But a cold month since then has stalled their emergence. A thermometer pushed into the forest soil today showed readings of 60 degrees and less—at least four degrees below the temperature needed to get the nymphs crawling out of the dirt to climb rocks and vegetation where they’ll molt, dry, and take flight.

A warm week ahead with daytime temperatures in the eighties and nighttime lows in the fifties and sixties, instead of in the forties, should get the woodland soils warming. Brood X Periodical Cicadas will be out and about in a jiffy—and you’ll hear all about it.

Yesterday, a hike through a peaceful ridgetop woods in the Furnace Hills of southern Lebanon County resulted in an interesting discovery. It was extraordinarily quiet for a mid-April afternoon. Bird life was sparse—just a pair of nesting White-breasted Nuthatches and a drumming Hairy Woodpecker. A few deer scurried down the hillside. There was little else to see or hear. But if one were to have a look below the forest floor, they’d find out where the action is.

2021 is an emergence year for Brood X, the “Great Eastern Brood”—the largest of the 15 surviving broods of Periodical Cicadas. After seventeen years as subterranean larvae, the nymphs are presently positioned just below ground level, and they’re ready to see sunlight. After tunneling upward from the deciduous tree roots from which they fed on small amounts of sap since 2004, they’re awaiting a steady ground temperature of about 64 degrees Fahrenheit before surfacing to climb a tree, shrub, or other object and undergo one last molt into an imago—a flying adult.

The woodlots of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed won’t be quiet for long. Loud choruses of male Periodical Cicadas will soon roar through forest and verdant suburbia. They’re looking for love, and they’re gonna die trying to find it. And dozens and dozens of animal species will take advantage of the swarms to feed themselves and their young. Yep, the woods are gonna be a lively place real soon.

Let’s take a quiet stroll through the forest to have a look around. The spring awakening is underway and it’s a marvelous thing to behold. You may think it a bit odd, but during this walk we’re not going to spend all of our time gazing up into the trees. Instead, we’re going to investigate the happenings at ground level—life on the forest floor.

There certainly is more to a forest than the living trees. If you’re hiking through a grove of timber getting snared in a maze of prickly Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) and seeing little else but maybe a wild ungulate or two, then you’re in a has-been forest. Logging, firewood collection, fragmentation, and other man-made disturbances inside and near forests take a collective toll on their composition, eventually turning them to mere woodlots. Go enjoy the forests of the lower Susquehanna valley while you still can. And remember to do it gently; we’re losing quality as well as quantity right now—so tread softly.

With autumn coming to a close, let’s have a look at some of the fascinating insects (and a spider) that put on a show during some mild afternoons in the late months of 2019.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

Second Mountain Hawk Watch is located on a ridge top along the northern edge of the Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation and the southern edge of State Game Lands 211 in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. The valley on the north side of the ridge, also known as St. Anthony’s Wilderness, is drained to the Susquehanna by Stony Creek. The valley to the south is drained toward the river by Indiantown Run, a tributary of Swatara Creek.

The hawk watch is able to operate at this prime location for observing the autumn migration of birds, butterflies, dragonflies, and bats through the courtesy of the Pennsylvania Game Commission and the Garrison Commander at Fort Indiantown Gap. The Second Mountain Hawk Watch Association is a non-profit organization that staffs the count site daily throughout the season and reports data to the North American Hawk Watch Association (posted daily at hawkcount.org).

Today, Second Mountain Hawk Watch was populated by observers who enjoyed today’s break in the rainy weather with a visit to the lookout to see what birds might be on the move. All were anxiously awaiting a big flight of Broad-winged Hawks, a forest-dwelling Neotropical species that often travels back to its wintering grounds in groups exceeding one hundred birds. Each autumn, many inland hawk watches in the northeast experience at least one day in mid-September with a Broad-winged Hawk count exceeding 1,000 birds. They are an early-season migrant and today’s southeast winds ahead of the remnants of Hurricane Florence (currently in the Carolinas) could push southwest-heading “Broad-wings” out of the Piedmont Province and into the Ridge and Valley Province for a pass by the Second Mountain lookout.

The flight turned out to be steady through the day with over three hundred Broad-winged Hawks sighted. The largest group consisted of several dozen birds. We would hope there are probably many more yet to come after the Florence rains pass through the northeast and out to sea by mid-week. Also seen today were Bald Eagles, Ospreys, American Kestrels, and a migrating Red-headed Woodpecker.

Migrating insects included Monarch butterflies, and the three commonest species of migratory dragonflies: Wandering Glider, Black Saddlebags, and Common Green Darner. The Common Green Darners swarmed the lookout by the dozens late in the afternoon and attracted a couple of American Kestrels, which had apparently set down from a day of migration. American Kestrels and Broad-winged Hawks feed upon dragonflies and often migrate in tandem with them for at least a portion of their journey.

Still later, as the last of the Broad-winged Hawks descended from great heights and began passing by just above the trees looking for a place to settle down, a most unwelcome visitor arrived at the lookout. It glided in from the St. Anthony’s Wilderness side of the ridge on showy crimson-red wings, then became nearly indiscernible from gray tree bark when it landed on a limb. It was the dreaded and potentially invasive Spotted Lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula). This large leafhopper is native to Asia and was first discovered in North America in the Oley Valley of eastern Berks County, Pennsylvania in 2014. The larval stage is exceptionally damaging to cultivated grape and orchard crops. It poses a threat to forest trees as well. Despite efforts to contain the species through quarantine and other methods, it’s obviously spreading quickly. Here on the Second Mountain lookout, we know that wind has a huge influence on the movement of birds and insects. The east and southeast winds we’ve experienced for nearly a week may be carrying Spotted Lanternflies well out of their most recent range and into the forests of the Ridge and Valley Province. We do know for certain that the Spotted Lanternfly has found its way into the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

It’s sprayed with herbicides. It’s mowed and mangled. It’s ground to shreds with noisy weed-trimmers. It’s scorned and maligned. It’s been targeted for elimination by some governments because it’s undesirable and “noxious”. And it has that four letter word in its name which dooms the fate of any plant that possesses it. It’s the Common Milkweed, and it’s the center of activity in our garden at this time of year. Yep, we said milk-WEED.

Now, you need to understand that our garden is small—less than 2,500 square feet. There is no lawn, and there will be no lawn. We’ll have nothing to do with the lawn nonsense. Those of you who know us, know that the lawn, or anything that looks like lawn, are through.

Anyway, most of the plants in the garden are native species. There are trees, numerous shrubs, some water features with aquatic plants, and filling the sunny margins is a mix of native grassland plants including Common Milkweed. The unusually wet growing season in 2018 has been very kind to these plants. They are still very green and lush. And the animals that rely on them are having a banner year. Have a look…

We’ve planted a variety of native grassland species to help support the milkweed structurally and to provide a more complete habitat for Monarch butterflies and other native insects. This year, these plants are exceptionally colorful for late-August due to the abundance of rain. The warm season grasses shown below are the four primary species found in the American tall-grass prairies and elsewhere.

There was Monarch activity in the garden today like we’ve never seen before—and it revolved around milkweed and the companion plants.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

There’s something frightening going on down there. In the sand, beneath the plants on the shoreline, there’s a pile of soil next to a hole it’s been digging. Now, it’s dragging something toward the tunnel it made. What does it have? Is that alive?

We know how the system works, the food chain that is. The small stuff is eaten by the progressively bigger things, and there are fewer of the latter than there are of the former, thus the whole network keeps operating long-term. Some things chew plants, others devour animals whole or in part, and then there are those, like us, that do both. In the natural ecosystem, predators keep the numerous little critters from getting out of control and decimating certain other plant or animal populations and wrecking the whole business. When man brings an invasive and potentially destructive species to a new area, occasionally we’re fortunate enough to have a native species adapt and begin to keep the invader under control by eating it. It maintains the balance. It’s easy enough to understand.

Late summer days are marked by a change in the sounds coming from the forests surrounding the falls. For birds, breeding season is ending, so the males cease their chorus of songs and insects take over the musical duties. The buzzing calls of male “Annual Cicadas” (Neotibicen species) are the most familiar. The female “Annual Cicada” lays her eggs in the twigs of trees. After hatching, the nymphs drop to the ground and burrow into the soil to live and feed along tree roots for the next two to five years. A dry exoskeleton clinging to a tree trunk is evidence that a nymph has emerged from its subterranean haunts and flown away as an adult to breed and soon thereafter die. Flights of adult “Annual Cicadas” occur every year, but never come anywhere close to reaching the enormous numbers of “Periodical Cicadas” (Magicicada species). The three species of “Periodical Cicadas” synchronize their life cycles throughout their combined regional populations to create broods that emerge as spectacular flights once every 13 or 17 years.

For the adult cicada, there is danger, and that danger resembles an enormous bee. It’s an Eastern Cicada Killer (Specius speciosus) wasp, and it will latch onto a cicada and begin stinging while both are in flight. The stings soon paralyze the screeching, panicked cicada. The Cicada Killer then begins the task of airlifting and/or dragging its victim to the lair it has prepared. The cicada is placed in one of more than a dozen cells in the tunnel complex where it will serve as food for the wasp’s larvae. The wasp lays an egg on the cicada, then leaves and pushes the hole closed. The egg hatches in a several days and the larval grub is on its own to feast upon the hapless cicada.

Other species in the Solitary Wasp family (Sphecidae) have similar life cycles using specific prey which they incapacitate to serve as sustenance for their larvae.

The Solitary Wasps are an important control on the populations of their respective prey. Additionally, the wasp’s bizarre life cycle ensures a greater survival rate for its own offspring by providing sufficient food for each of its progeny before the egg beginning its life is ever put in place. It’s complete family planning.

The cicadas reproduce quickly and, as a species, seem to endure the assault by Cicada Killers, birds, and other predators. The Periodical Cicadas (Magicicada), with adult flights occurring as a massive swarm of an entire population every thirteen or seventeen years, survive as species by providing predators with so ample a supply of food that most of the adults go unmolested to complete reproduction. Stay tuned, 2021 is due to be the next Periodical Cicada year in the vicinity of Conewago Falls.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.