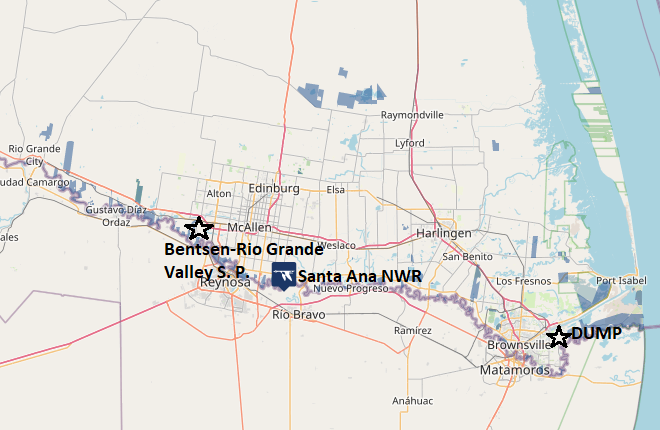

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY ELEVEN—May 31, 1983

“AOK Camp, Texas — 7 Miles S. of Kingsville”

“Went south to the 1st rest stop south of Sarita — No Tropical Parula. Lots of other birds. We added Summer Tanager and Lesser Goldfinch.”

The Sarita Rest Area along Route 77 was like a little oasis of taller trees in the Texas scrubland. We received reports from the birders we met yesterday at Falcon Dam that recently, Tropical Parula had been seen there. We searched the small area and listened carefully, but to no avail. For these warblers, nesting season was over. We were surprised to find Lesser Goldfinches in the trees. Back in 1983, the coastal plain of Texas was pretty far east for the species. Steve was a bit skeptical when we first spotted them, but once they came into plain view, he was a believer. I recall him finally exclaiming, “They are Lesser Goldfinches.” Summer Tanager was another wonderful surprise. Today, the Sarita Rest Area remains a stopping point for birders in south Texas. Both Lesser Goldfinch and Tropical Parula were seen there this spring.

After our roll of dice at the Sarita Rest Area, we continued south through the King Ranch en route back to Brownsville.

“Saw a Coyote on the way.”

“Took Steve to the airport and drove out to Boca Chica where Harold went swimming.”

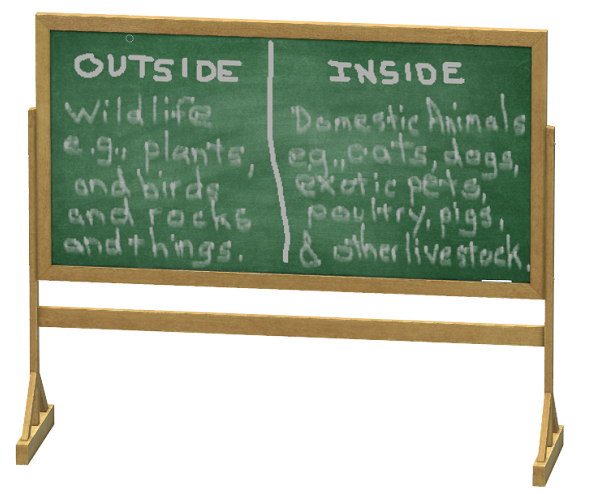

The drive from Brownsville out Boca Chica Boulevard to the Gulf of Mexico passes through about 18 miles of the outermost flats of the river delta that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley. This area is of course susceptible to the greatest impacts from tropical weather, especially hurricanes. During our visit, we passed a small cluster of ranch houses about two or three miles from the beach. This was the village known as Boca Chica. Otherwise, the area was desolate and left to the impacts of the weather and to the wildlife.

The mouth of the Rio Grande, and thus the international border with Mexico, was and still is about two miles south of Boca Chica Beach. Before the construction of dams and other flood control measures on the river, the path of the Rio Grande through the alluvium deposits on this outer section of delta would vary greatly. Accumulations of eroded material, river flooding, tides, and storms would conspire to change the landscape prompting the river to seek the path of least resistance and change its course. Surrounding the segments of abandoned channel, these changes leave behind valuable wetlands including not only the resacas of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, but similar features in tidal sections of the outer delta. When left to function in their natural state, deltas manage silt and pollutants in the waters that pass through them using ancient physical, biological, and chemical processes that require no intervention from man.

Harold was determined to go for a swim in the Gulf of Mexico before boarding a flight home. We all liked the beach. Why not? You may remember trips to the shore in the summertime. Back in the pre-casino days, we used to go to Atlantic City, New Jersey, to visit Steel Pier. For the first three quarters of the twentieth century, Steel Pier was the Jersey Shore’s amusement park at sea. There were rides, food stands, arcades, daily concerts with big name acts, diving shows, and ballroom dances.

There were, back then, attractions at Steel Pier that were creatively promoted to give the visitor the impression that they were going to see something more profound or amazing than was was delivered. You know, things advertised to draw you in, but its not quite what you expected.

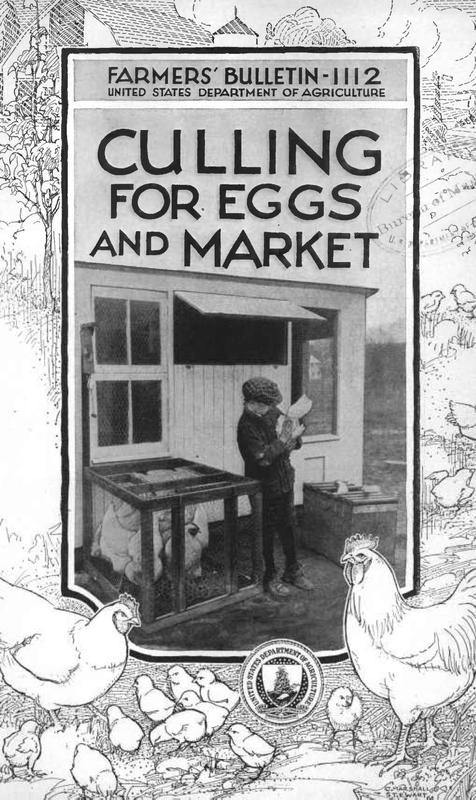

For example, there was an arcade game promising to show you a chicken playing baseball. Okay, I’ll bite. Turns out the chicken did too. You put your money in the machine and watched as the chicken came out and rounded the diamond eating poultry food as it was offered at each of the bases. Hmmm…to suggest that this was a chicken playing baseball seems like a bit of a stretch.

They had a diving bell there too. Wow! We’ll go below the waves and view the fish, octopi, and other sights through the water-tight windows while we descend to the ocean floor. You would pay to get inside, then they would lower the bell down through a hole in the pier. Once below the rolling surf, you would get to look at the turbid seawater sloshing around at the window like dirty suds in a washing machine. If you were lucky, some trash might briefly get stuck on the glass. To imply that this was a chance to see life beneath waves was B. S., and I don’t mean bathysphere.

Then there was a girl riding a diving horse. You would hike all the way to the end of the pier and watch the preliminary show with these divers plunging through a hole in the deck and into the choppy Atlantic below. They were very good, but no, we never saw Rodney Dangerfield do a “Triple Lindy” there. And then it was time for the finale. Wow, is that horse going to dive in the ocean? How do they get the horse back up on the pier? Forget it. Instead of that, they walked poor Mr. Ed up a ramp into a box, then the girl climbs on his back, the door opens, and she nudges Ol’ Ed to into a plunge followed by a thumping splash into a swimming pool on the deck. Not bad, but not what we were expecting. Since we had to walk almost a quarter of a mile out to sea to get there, they kinda led us to believe that the amazing equine was going to leap into the Atlantic—horse hockey!

Preceding all this fun was a guy back in the early 1930s, William Swan, who, in June 1931, flew a “rocket-powered plane” at Bader Field outside Atlantic City. The plane was actually a glider on which a rocket was fired producing about 50 pounds of thrust to boost it airborne after assistants got it rolling by pushing it. In newspaper articles and on newsreels afterward, he would promote the future of rocket planes carrying passengers across the ocean at 500 miles per hour. Using a glider equipped with pontoons for landing in the ocean, he promised to make several flights daily from Steel Pier. Those who came to see him may have, at best, watched him fire small rockets he had attached to his craft—little more.

What does all this have to do with Boca Chica Beach? It turn out two years later, William Swan is hyping a new innovation—a rocket-powered backpack. He’d demonstrate it during a skydiving exhibition at the Del-Mar Beach Resort, a cluster of 20 cabins and community buildings on Boca Chica Beach. According to his deceptive promotions, Swan would jump out of a plane and light flares as he fell. Then he’d ignite the backpack rocket and land on the shoreline in front of the crowd. The event was expected to draw 3,000 carloads of people. When the big day came, just over 1,000 cars showed up. The event was a bust and the weather was bad, cloudy with a mist over the gulf. During a break in the clouds, the pilot took Swan aloft. Swan ordered him out to sea and to 8,500 feet, a higher altitude than planned. Then he jumped. He dropped the flares, which didn’t then ignite, and neither did the rocket. He opened his chute at 6,000 feet and the crowd watched as Swan drifted into the mist offshore and was never seen again. There were rumors both that he used the stunt as a way to flee to Mexico to start a new life and that he had committed suicide. Others believed he died accidentally. To learn the full story of Billy Swan, check out The Rocketeer Who Never Was, by Mark Wade.

Forward fifty years to our visit to Boca Chica Beach. The Del-Mar Beach Resort, built in the 1920s as a cluster of 20 cabins and a ballroom, was gone. It was destroyed by a hurricane later in the same year Swan disappeared—1933. The resort, which was hoped would be the start of a seaside vacation city, never reopened. In 1983, we saw just a handful of beach goers and the birds, that’s it. One could look down to the south and see the area of the Rio Grande’s mouth and Mexico, but there were no structures of note. It was peaceful and alive with wildlife. We were sorry we didn’t have more time there.

“Here we added Least Tern, Brown Pelican and Sandwich Tern.”

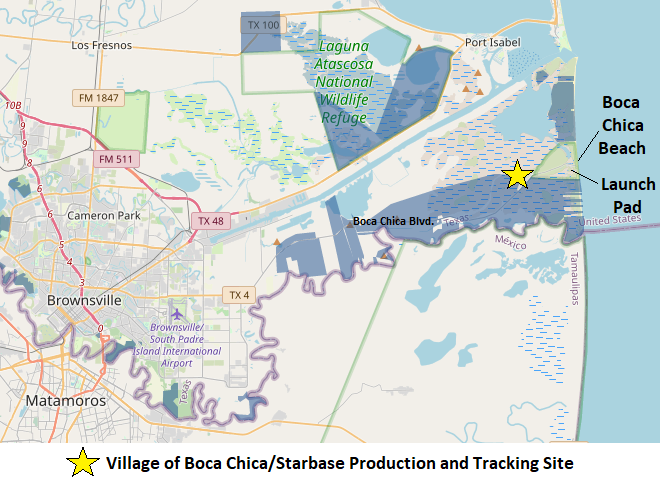

Today, the Village of Boca Chica and Boca Chica Beach are the location of SpaceX’s South Texas Launch Facility. Those of the village’s ranch houses built in 1967 that have survived hurricane devastation over the years have been incorporated into the “Starbase” production and tracking facility. The launch pad and testing area is along the beach just behind the dunes at the end of Boca Chica Boulevard.

The latest launch, just more than a month ago, was the maiden flight of “Starship”, a 394-foot behemoth that is the largest rocket ever flown. The “Super Heavy Booster” first stage’s 33 Raptor engines produce 17.1 million pounds of thrust making Starship the most powerful rocket ever flown. See, things really are bigger in Texas.

Last month’s unmanned orbital test launch ended when the Starship spacecraft failed to separate at staging. As the booster section commenced its roll manuever to return to the launch pad, the entire assembly began tumbling out of control. It exploded and rained debris into the gulf along a stretch of the downrange trajectory.

Development of Starbase is opposed by many due to noise, safety, and environmental concerns. Boca Chica Boulevard (Texas Route 4) is frequently closed due to activity at the launch pad site, thus excluding residents and tourists from visiting the beach. With over 1,200 people already working at Starbase, demand for housing in the Brownsville area has increased. Some have accused SpaceX CEO Elon Musk of promoting gentrification of the area—running up housing prices to force out the lower-income residents. He has responded with a vision of a new city at Boca Chica, his “space port”.

Does history have an applicable lesson for us here? When Musk talks about going to the Moon and Mars, or ferrying a hundred people around the world on his Starship, is it just another Steel Pier-style deception? Is Musk a modern-day William Swan? A very talented marketer? Could be. And is the whole thing setting up a large-scale replay of the Del-Mar Beach Resort’s demise in 1933? Is building a city on the outer edges of a river delta asking for an outcome similar to the one suffered by New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina? It’s likely. After all, building on or near a beach, floodplain, or delta is a short-sighted venture to begin with. If the party doing the developing doesn’t suffer the consequences of defying the laws of nature, one of the poor suckers in the successive line of buyers and occupants will. This isn’t rocket science folks. Its weather, climate, and erosion, and its been altering coastlines, river courses, and the composition and distribution of life forms on this planet for millions of years. And guess what. These factors will continue to alter Earth for millions of years more after man the meddler is long gone. You’re not going to stop their effects, and you’re not going to escape their wrath by ignoring them. So if you’re smart, you’ll get out of their way and stay there!

Billy Swan was probably broke when he came to Boca Chica. He reportedly borrowed 20 bucks from the resort operator just to cover his personal expenses during his backpack rocket event. Elon Musk comes to Boca Chica with over 100 billion dollars and capital from other private investors to boot. Despite some obvious exaggerations about colonizing the Moon, Mars, and other celestial bodies, he just might be able to at least get people there for short-term visits. And that’s quite an accomplishment.

“Then took Harold to the airport. We left him at 3:30 and headed north on Route 77, got as far as Victoria. Had a flat on the way. Larry had the spare on in 10 minutes. We stopped at a picnic area for the nite, because we could not find the camping area.”

If we were going to have a flat, we had it at the right place. We were just outside Raymondville, Texas, at a newly constructed highway interchange. The wide, level shoulder allowed us to get the camper off to the side of the road in a safe place to jack it up and change the tire. Easy. We were thereafter homeward bound.