Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY TWELVE—June 1, 1983

“KOA Hammond, LA”

“We stopped early today — About 2:30 P.M. Cleaned the interior of the camper, washed the windows, and put everything where it belonged. The windshield was a buggy mess. Had supper according to the menu. Took pictures of the place. Had a shower. Loafed all evening.”

After being on the go for twelve to sixteen hours a day for more than a week, it was nice to catch up on our “housekeeping”, field notes, and rest. The campground, which was yet another nearly empty one, had an in-ground pool, so I decided to go for a swim. As I went through the gate, I noticed that the water was a little bit dull, not sparkling clear as if treated by the usual dose of chemicals. Upon getting closer, I could see what looked like a layer of mulm at the bottom of the pool, similar to the detritus and waste that accumulates atop the substrate in an otherwise clear aquarium tank. Needless to say, I postponed the swim. Later, when we happened to be in the office, I asked the owners about the pool and was momentarily puzzled when they told us that the entire campground had been flooded last month. This was at first surprising because no stream, creek, or river was in sight, but the land is so flat and the elevation so uniform in southwestern Louisiana that a couple of feet of water can inundate miles and miles of these lowlands. As on a beach or on a delta, building anything of value in a floodplain is risky business.

On June 2, we resumed our drive, then spent the night at the KOA campground in Sweetwater, Tennessee, at the same accommodations we visited while southbound on May 21. There, I finally had my refreshing swim. By the following evening, June 3, we had arrived back in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. During the trip from the Brownsville Airport to Lititz, Pennsylvania, the odometer had registered 1,945 miles.

This then, prompted and fortified by the notes kept by Russ Markert, have been your editor’s recollections from his ever-evaporating river of memories of an adventure forty years gone. I hope you’ve enjoyed this modern-style slide show describing our journey to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. I’m grateful to each of my traveling companions for inviting me to share this experience with them and am equally glad to have had the opportunity to share the story of our trip with you.

If traveling to see the wildlife and plant communities of south Texas seems like something that might interest you, I strongly urge you to go. Many more tropical species, including native parrots, are now found north of the border and the opportunity to see vagrants is still better there than anywhere else in the country. The hundreds of species of butterflies and the spectacular migrations of the Neotropical birds that nest here in the the higher latitudes make it a place you need to visit at least once in a lifetime. The cooler months of the year can be a comfortable time to make the trip. You’ll see wintering birds from both eastern and western portions of the United States and Canada, some in numbers that might amaze you.

If the Lower Rio Grande Valley is something outside your means, then may I suggest a visit to ZooAmerica in Hershey, Pennsylvania. The theme of the collection is North American wildlife and the self-guided tour is organized by regional habitat types including the southern swamps and the southwestern deserts and scrubland. Some of the animals we saw on our expedition, and some that we missed, are among the species under their care.

That’s it folks. Until next time, adiós amigos.

IN MEMORIAM

J. E. Russel Markert (1912-1984)

Harold B. Morrin (1924-2012)

Steven J. Santner (1948-2021)

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY FOUR—May 24, 1983

“AOK Campground—South of Kingsville, Texas”

“Arose at 6:30 A.M. to the tune of Common Nighthawks. After breakfast, we headed for Harlingen. While driving south we saw six pairs of Black-bellied Whistling Ducks. At Harlingen we phoned Father Tom, who is an expert birder for the area.”

As we drove south to Harlingen, much our 100-mile route was through the Laureles division of the King Ranch, the largest ranch in the United States. It covers over 800,000 acres and is larger than the state of Rhode Island. The road there was as straight as an arrow with wire fences on both sides and scrubland as far as the eye could see. Things really are bigger in Texas.

Once in Harlingen, we did two things no one needs to do anymore:

Today, nearly everyone traveling such distances to find birds is carrying a cellular phone and many can use theirs to access internet sites and databases such as eBird to get current sighting information. Back in 1983, Father Tom Pincelli was a dear friend to birders visiting the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Few places had a person who was willing to answer the phone and field inquiries regarding the latest whereabouts of this or that bird. To remain current, he also had to religiously (forgive me for the pun) collect sighting information from the observers with whom he had contact. For locations elsewhere across the country, a birder in 1983 was happy just to have a phone number for a hotline with a tape-recorded message listing the unusual sightings for its covered region. If you were lucky, the volunteer logging the sightings would be able to update the tape once a week. For those who dialed his number, Father Tom provided an exceptionally personal experience.

Since 1983, Father Tom Pincelli, also known as “Father Bird”, has tirelessly promoted birding and conservation throughout the Lower Rio Grande Valley. His efforts have included hosting a P.B.S. television program and writing columns for local newspapers. He has been instrumental in developing the annual Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival. The public sentiment he has generated for the birding paradise that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley has helped facilitate the acquisition and/or protection of many key parcels of land in the region.

“After receiving information on locations of Tropical Parula, Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, Hook-billed Kite, Brown Jay, and Clay-colored Robin, we went on to check out the Brownsville Airport where we will meet Harold and Steve Thursday noon.”

If we were going to see these five species in the American Birding Association listing area, then we would have to see them in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. All five were target birds for each of us, including Harold who had few other possibilities for new species on the trip. Father Tom provided us with tips for finding each.

I noticed as we began moving around Harlingen and Brownsville that Russ was swiftly getting his bearings—he had been here before and was starting to remember where things were. His ability to navigate his way around allowed us to keep moving and see a lot in a short time.

In Harlingen, we easily found Mourning Doves and the non-native Rock Pigeons, species we see regularly in Pennsylvania. We became more enthusiastic about doves and pigeons soon after when we saw the first of the several other species native to south Texas, the diminutive Inca Dove (Columbina inca), also known as the Mexican Dove.

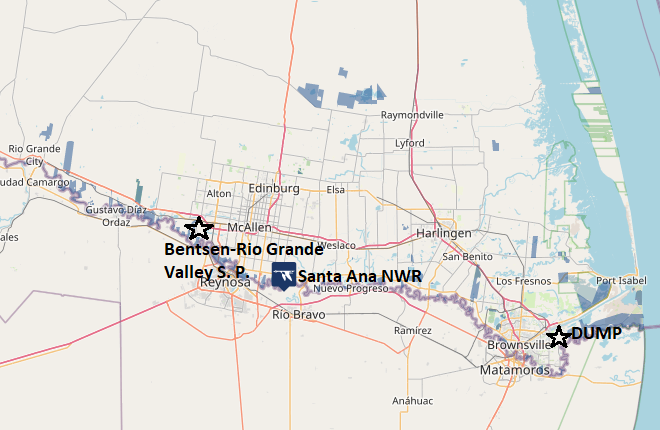

“Next, to the Brownsville Dump to see the White-necked Ravens — Then to Mrs. Benn’s in Brownsville for the Buff-bellied Hummingbird. Both lifers for Larry.”

For birders wanting to see a White-necked Raven in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the Brownsville Dump was the place to go. With very little effort—excluding a trip of nearly 2,000 miles to get there—we found them. Today, birders still go to the Brownsville Dump to find White-necked Ravens, though the dump is now called the Brownsville Landfill and the bird is known as the Chihuahuan Raven (Corvus cryptoleucus).

Mrs. Benn’s home was in a verdant residential neighborhood in Brownsville. She welcomed birders to come and see the Buff-bellied Hummingbirds that visited her feeder filled with sugar water. I don’t recall whether or not she kept a guest book for visitors to sign, but if she did, it would have included hundreds—maybe thousands—of names of people from all over North America who came to her garden to get a look at a Buff-bellied Hummingbird. After arriving, we waited a short time and sure enough, we watched a Buff-bellied Hummingbird (Amazilia yucatanensis) sipping Mrs. Benn’s home-brewed nectar from her glass feeder. This emerald hummingbird is primarily a Mexican species with a breeding range that extends north into the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. When not breeding, a few will wander north and east along the Gulf Coastal Plain as far as Florida.

Other finds at Mrs Benn’s included White-winged Dove (Zenaida asiatica), Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens), Brown-crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus tyrannulus), and Black-crested Titmouse (Baeolophus atricristatus), a species also known as Mexican Titmouse.

The Lower Rio Grande Valley from Rio Grande City east to the Gulf of Mexico is actually the river’s outflow delta. At least six historic channels have been delineated in Texas on the north side of the river’s present-day course. An equal number may exist south of the border in Mexico. Hundreds of oxbow lakes known as “resacas” mark the paths of the former channels through the delta. Many resacas are the centerpieces of parks, wildlife refuges, and housing developments. Still others are barely detectable after being buried in silt deposits left by the meandering river. Channelization, land disturbances related to agriculture, and a boom in urbanization throughout the valley have disconnected many of the most recently formed resacas from the river’s floodplain, preventing them from absorbing the impact of high-water events. These alterations to natural morphology can severely aggravate flooding and water pollution problems.

“On to Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. We walked to Pintail Lake and saw 6 Black-bellied Whistling Ducks and 2 Mississippi Kites and 1 Pied-billed Grebe. We drove the route thru the park with great results—Anhingas, Least Grebe, and more Black-bellied Whistling Ducks.

Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge on the Rio Grande is not only a birder’s mecca, 300 species of butterflies have been identified there. That’s half the species known to occur in the United States! Its subtropical riparian forest and resaca lakes provide habitat for hundreds of migratory and resident bird species including many Central and South American species that reach the northern limit of their range in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Two endangered cats occur in the park—the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and the Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi).

We saw no cats at Santa Ana, but did quite well with the birds. Our list included the species listed above plus Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis); Louisiana Heron, now known as Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor); Plain Chachalacas; Purple Gallinule; Common Gallinule (Gallinula galeata); American Coot; Killdeer; Greater Yellowlegs; the coastal Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla); and its close relative of the central flyway and continental interior, the Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan). Others finds were White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, Inca Dove, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Ladder-backed Woodpecker (Dryobates scalaris), Brown-crested Flycatcher, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and House Sparrow. A real standout was the colorful Green Jay (Cyanocorax luxosus), yet another tropical Central American species found north only as far as the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

“We were unlucky not to find a campground at McAllen, so we went on to Bentsen State Park where we got a camp spot. After a sauerkraut supper, we birded till dark, then showered and wrote up the log. Very hot today.”

Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, like the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, is located along the Rio Grande river and features dense subtropical riparian forest that grows in the naturally-deposited silt levees of the floodplain surrounding several lake-like oxbow resacas. Montezuma Bald Cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) is a native specialty found there but nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley. During our visit, we marveled at the epiphyte Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) adorning many of the more massive trees in the park. Willows lined much of the river shoreline.

Over time, flood control projects such as man-made dams, drainage ditches, and levees have impaired stormwater capture and aquifer recharge in the floodplain. These alterations to watershed hydrology have resulted in drier soils in many sections of the Lower Rio Grande Valley’s riparian forests. Where drier conditions persist, xeric (dry soil) scrubland plants are slowly overtaking the moisture-dependent species. As a result, the park’s woodlands are composed of trees with a variety of microclimatic requirements—Anaqua (Ehretia anacua), Cedar Elm (Ulmus crassifolia), Texas Ebony (Ebenopsis ebano), hackberry, mesquite, Mexican Ash (Fraxinus berlandieriana), retama, and tepeguaje are the principle species. The park’s subtropical Texas Wild Olive (Cordia boissieri) grows in the wild nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

While a majority of birders visiting Benten-Rio Grande State Park come to see the more tropical specialties of the riparian woods, searching the brushy habitat of the park’s scrubland can afford one the opportunity to see species typical of the southwestern United States and deserts of Mexico. This scrubland of the Lower Rio Grande Valley is part of the Tamaulipan Mezquital ecoregion, an area of xeric (dry soil) shrublands and deserts that extends northwest from the delta through most of south Texas and into the bordering provinces of northeastern Mexico.

Our campsite was located in prime birding habitat. We were a short walk away from one of the park’s flooded oxbow resacas and vegetation was thick along the roadsides. It was no surprise that the place abounded with birds. An evening stroll yielded Plain Chachalaca, White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, White-fronted Dove, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Brown-crested Flycatcher, Green Jay, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and Bronzed Cowbird (Molothrus aeneus). At nightfall, we listened to the calls of an Eastern Screech Owl (Megascops asio), Common Nighthawks, and Common Pauraque (Nyctidromus albicollis), a nightjar of Central and South America that nests only as far north as the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The Common Pauraque is the tropical counterpart of the Eastern Whip-poor-will, a Neotropical migrant that nests in scattered forest locations throughout eastern North America.

I would note that we saw no “snowbirds”—long-term vacationers from the northern states and Canada who fill the park through the cooler months of fall, winter, and spring. They were gone for the summer. But for a few other friendly folks, we had the entire campground to ourselves for the duration of our stay.

And now, a few words from the old watersnake who happens to live down along the creek where last spring’s Earth Day events were held.

Hey! You! Yeah You! I heard that there won’t be an Earth Day celebration down here this week. What a ssshame!

Remember how much fun we had last year. All those kids ssscrambling down along the creek bank throwing ssstones and ssscreaming and yelling like they’re gonna sssack a city. I ssshould have had the sssense to ssslither away. But no, I just curled up and played it cool. But sssure enough, one of the little brats found me and bellowed out loud enough for the whole countryside to hear, “SSSNAAAAKE!”

Ah nuts. That’s all it took. Here they come. Poking me with a ssstick. Taunting and ssstabbing. Don’t you know that hurts? What did I ever do to you, you rotten little apes? I’m telling ya, I get no respect.

Think that’s bad? It got worse. Don’t you remember? After a dozen of the runny-nosed monsters had me sssurrounded, one of the brain-dead adults yelled, “…it might be poisonous!”

That’s all it took. The ssstones got hurled my way and the poking with a ssstick became beatings. Those rats tried to kill me! On Earth Day! I ssslid into deep water and barely escaped with my life.

Now I want to tell you a few things—let’s get ’em ssstraight right now. I’m not, nor is any other watersnake in the SSSusquehanna valley, poisonous. Ssso don’t go villainizing me and those like me just because you have a monkey-like fear of us and need a sssocially acceptable reason to exercise your murderous instincts. Yeah, we know all about your manly tall tales of conquest that you ssshamelessly tell your friends and family after you kill a sssnake. Wanna be a hero? Then leave us alone! We and all of the native sssnakes of the SSSusquehanna valley, including the venomous copperheads and Timber Rattlesnakes, are minding our own business and just want to be left alone. Get it? Leave us alone! Don’t beat us with a ssshovel, mow over us, drive your car or truck over us, or ssshoot us. We have it bad enough as it is. You already buggered up most of our homes building your roads, houses, and lawns you know—so have a little respect. And one more thing, we don’t want be part of your pet menagerie. There’s no way we’ll “love you” or want anything to do with you, even if you do imprison us and make us sssubmissive to you for food, you sssick fascists. And that goes for you obsessive collector types too. We know you’re hoarding animals like us and calling your cruel little pet penitentiary a “rescue”. Yeah, we’re wise to that con too.

Ssso we’ve heard you won’t be coming down to the creek to terrorize us this year. No Earth Day event, huh. Well good, because I can’t take another Earth Day. Let the sssquirrels and the birds plant the trees, they do a better job than you anyway. Ssstay at home where you belong—watching television or twit-facing your B.F.F. on that magic box you carry around. And if you absolutely feel the urge to be upset by a sssnake in your midst, go visit that neighbor with the “reptile rescue”, I’m sssure he has a cobra or some other non-native sssnake in his collection that really ought to give you worry—especially when it finally escapes that prison.

A moderate breeze from the south placed a headwind into the face of migrants trying to wing their way to winter quarters. The urge to reach their destination overwhelmed any inclination a bird or insect may have had to stay put and try again another day.

Blue Jays were joined by increasing numbers of American Robins crossing the river in small groups to continue their migratory voyages. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and a handful of sandpipers headed down the river route. Other migrants today included a Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis), and a few Common Mergansers (Mergus merganser), House Finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), and Common Grackles (Quiscalus quiscula).

The afternoon belonged to the insects. The warm wind blew scores of Monarchs toward the north as they persistently flapped on a southwest heading. Many may have actually lost ground today. Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) and Cloudless Sulphur butterflies were observed battling their way south as well. All three of the common migrating dragonflies were seen: Common Green Darner (Anax junius), Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens), and Black Saddlebags (Tramea lacerata).

The warm weather and summer breeze are expected to continue as the rain and wind from Hurricane Nate, today striking coastal Alabama and Mississippi, progresses toward the Susquehanna River watershed during the coming forty-eight hours.