A glimpse of the rowdy guests crowding the Thanksgiving Day dinner table at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters…

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

A glimpse of the rowdy guests crowding the Thanksgiving Day dinner table at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters…

During the recent couple of mornings, a tide of Neotropical migrants has been rolling along the crests of the Appalachian ridges and Piedmont highlands of southern Pennsylvania. In the first hours of daylight, “waves” of warblers, vireos, flycatchers, tanagers, and other birds are being observed flitting among the sun-drenched foliage as they feed in trees along the edges of ridgetop clearings. Big fallouts have been reported along Kittattiny Ridge/Blue Mountain at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and at Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch. Birds are also being seen in the Furnace Hills of the Piedmont.

Here are some of the 300 to 400 warblers (a very conservative estimate) seen in a “wave” found working its way southwest through the forest clearing at the Second Mountain Hawk Watch in Lebanon County this morning. The feeding frenzy endured for two hours between 7 and 9 A.M. E.D.T.

Not photographed but observed in the mix of species were several Black-throated Blue Warblers and American Redstarts.

In addition to the warblers, other Neotropical migrants were on the move including two Common Nighthawks, a Broad-winged Hawk, a Least Flycatcher (Empidonax minimus), and…

Then, there was a taste of things to come…

Seeing a “wave” flight is a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Visiting known locations for observing warbler fallouts such as hawk watches, ridgetop clearings, and peninsular shorelines can improve your chances of witnessing one of these memorable spectacles by overcoming the first variable. To overcome the second, be sure to visit early and often. See you on the lookout!

The annual arrival of hoards of American Robins to devour the fruits found on the various berry-producing shrubs and trees in the garden at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters happened to coincide with this morning’s bitter cold temperatures. Here are photos of some of those hungry robins—plus shots of the handful of other songbirds that joined them for a frosty feeding frenzy.

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

Yesterday, a hike through a peaceful ridgetop woods in the Furnace Hills of southern Lebanon County resulted in an interesting discovery. It was extraordinarily quiet for a mid-April afternoon. Bird life was sparse—just a pair of nesting White-breasted Nuthatches and a drumming Hairy Woodpecker. A few deer scurried down the hillside. There was little else to see or hear. But if one were to have a look below the forest floor, they’d find out where the action is.

2021 is an emergence year for Brood X, the “Great Eastern Brood”—the largest of the 15 surviving broods of Periodical Cicadas. After seventeen years as subterranean larvae, the nymphs are presently positioned just below ground level, and they’re ready to see sunlight. After tunneling upward from the deciduous tree roots from which they fed on small amounts of sap since 2004, they’re awaiting a steady ground temperature of about 64 degrees Fahrenheit before surfacing to climb a tree, shrub, or other object and undergo one last molt into an imago—a flying adult.

The woodlots of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed won’t be quiet for long. Loud choruses of male Periodical Cicadas will soon roar through forest and verdant suburbia. They’re looking for love, and they’re gonna die trying to find it. And dozens and dozens of animal species will take advantage of the swarms to feed themselves and their young. Yep, the woods are gonna be a lively place real soon.

Thoughts of October in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed bring to mind scenes of brilliant fall foliage adorning wooded hillsides and stream courses, frosty mornings bringing an end to the growing season, and geese and other birds flying south for the winter.

The autumn migration of birds spans a period equaling nearly half the calendar year. Shorebirds and Neotropical perching birds begin moving through as early as late July, just as daylight hours begin decreasing during the weeks following their peak at summer solstice in late June. During the darkest days of the year, those surrounding winter solstice in late December, the last of the southbound migrants, including some hawks, eagles, waterfowl, and gulls, may still be on the move.

During October, there is a distinct change in the list of species an observer might find migrating through the lower Susquehanna valley. Reduced hours of daylight and plunges in temperatures—particularly frost and freeze events—impact the food sources available to birds. It is during October that we say goodbye to the Neotropical migrants and hello to those more hardy species that spend their winters in temperate climates like ours.

The need for food and cover is critical for the survival of wildlife during the colder months. If you are a property steward, think about providing places for wildlife in the landscape. Mow less. Plant trees, particularly evergreens. Thickets are good—plant or protect fruit-bearing vines and shrubs, and allow herbaceous native plants to flower and produce seed. And if you’re putting out provisions for songbirds, keep the feeders clean. Remember, even small yards and gardens can provide a life-saving oasis for migrating and wintering birds. With a larger parcel of land, you can do even more.

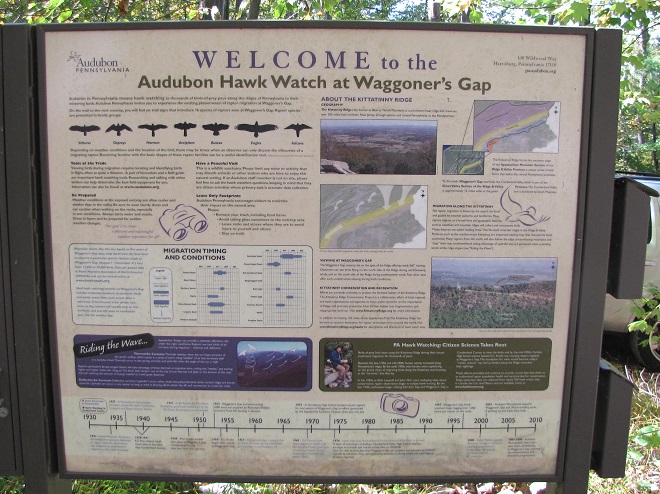

Nothing beats spending a day at a hawk watch lookout—except of course spending a day at a hawk watch lookout when the birds are parading through nonstop for hours on end.

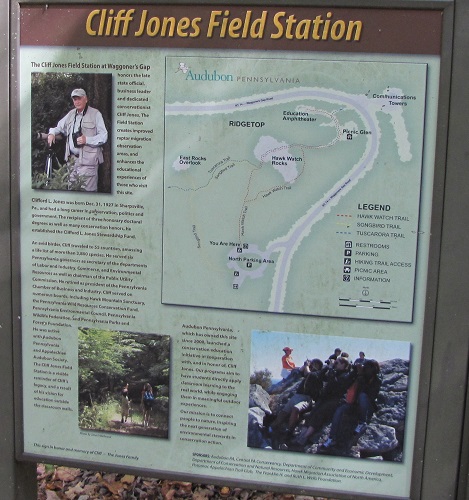

Check out Waggoner’s Gap, a hawk count site located on the border of Cumberland and Perry Counties atop Blue Mountain just north of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. It is by far the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s best location for observing large numbers of migrating raptors during the October and November flights.

Waggoner’s Gap is a hardy birder’s paradise. During the latter portion of the season, excellent flights often occur on days that follow the passage of a cold front and have strong northwest winds. But be prepared, it can be brutal on those rocks during a gusty late-October or early-November day after the leaves fall—so dress appropriately.

To see the daily totals for the raptor count at Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch and other hawk watches in North America, and to learn more about each site, be sure to visit hawkcount.org

When wild food crops such as pine cones, acorns, berries, and other tree seeds fail in the forests of Canada, bird species which may have otherwise remained north of the eastern United States for winter pay us a visit. There was a hint that such an event would occur this year when Red-breasted Nuthatches (Sitta canadensis) became widespread throughout the Mid-Atlantic States beginning in August. Then there were big flights of Blue Jays in recent weeks, an indication that the oaks of the northern wood are producing a less than optimal mast crop.

Reports of Pine Siskins (Spinus pinus), songbirds very similar in shape and size to the familiar American Goldfinch, have been posted from hawk watch sites throughout the region for several weeks now. During the last several days though, the numbers have increased to indicate that an invasion is underway. Just yesterday, nearly two thousand were seen from the lookout in Cape May Point, New Jersey. Just after sunrise this morning, between twenty and thirty Pine Siskins descended upon the hemlocks at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters. There, they began feeding on the abundant cone crop—then they quickly discovered the accommodations offered by the bird bath and feeders.

Is this the same Conewago Falls I visited a week ago? Could it really be? Where are all the gulls, the herons, the tiny critters swimming in the potholes, and the leaping fish? Except for a Bald Eagle on a nearby perch, the falls seems inanimate.

Yes, a week of deep freeze has stifled the Susquehanna and much of Conewago Falls. A hike up into the area where the falls churns with great turbulence provided a view of some open water. And a flow of open water is found downstream of the York Haven Dam powerhouse discharge. All else is icing over and freezing solid. The flow of the river pinned beneath is already beginning to heave the flat sheets into piles of jagged ice which accumulate behind obstacles and shallows.