Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Grasshoppers are perhaps best known for the occasions throughout history when an enormous congregation of these insects—a “plague of locusts”—would assemble and rove a region to feed. These swarms, which sometimes covered tens of thousands of square miles or more, often decimated crops, darkened the sky, and, on occasion, resulted in catastrophic famine among human settlements in various parts of the world.

The largest “plague of locusts” in the United States occurred during the mid-1870s in the Great Plains. The Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus), a grasshopper of prairies in the American west, had a range that extended east into New England, possibly settling there on lands cleared for farming. Rocky Mountain Locusts, aside from their native habitat on grasslands, apparently thrived on fields planted with warm-season crops. Like most grasshoppers, they fed and developed most vigorously during periods of dry, hot weather. With plenty of vegetative matter to consume during periods of scorching temperatures, the stage was set for populations of these insects to explode in agricultural areas, then take wing in search of more forage. Plagues struck parts of northern New England as early as the mid-1700s and were numerous in various states in the Great Plains through the middle of the 1800s. The big ones hit between 1873 and 1877 when swarms numbering as many as trillions of grasshoppers did $200 million in crop damage and caused a famine so severe that many farmers abandoned the westward migration. To prevent recurrent outbreaks of locust plagues and famine, experts suggested planting more cool-season grains like winter wheat, a crop which could mature and be harvested before the grasshoppers had a chance to cause any significant damage. In the years that followed, and as prairies gave way to the expansive agricultural lands that presently cover most of the Rocky Mountain Locust’s former range, the grasshopper began to disappear. By the early years of the twentieth century, the species was extinct. No one was quite certain why, and the precise cause is still a topic of debate to this day. Conversion of nearly all of its native habitat to cropland and grazing acreage seems to be the most likely culprit.

In the Mid-Atlantic States, the mosaic of the landscape—farmland interspersed with a mix of forest and disturbed urban/suburban lots—prevents grasshoppers from reaching the densities from which swarms arise. In the years since the implementation of “Green Revolution” farming practices, numbers of grasshoppers in our region have declined. Systemic insecticides including neonicotinoids keep grasshoppers and other insects from munching on warm-season crops like corn and soybeans. And herbicides including 2,4-D (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) have, in effect, become the equivalent of insecticides, eliminating broadleaf food plants from the pasturelands and hayfields where grasshoppers once fed and reproduced in abundance. As a result, few of the approximately three dozen species of grasshoppers with ranges that include the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are common here. Those that still thrive are largely adapted to roadsides, waste ground, and small clearings where native and some non-native plants make up their diet.

Here’s a look at four species of grasshoppers you’re likely to find in disturbed habitats throughout our region. Each remains common in relatively pesticide-free spaces with stands of dense grasses and broadleaf plants nearby.

CAROLINA GRASSHOPPER

Dissosteira carolina

DIFFERENTIAL GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus differentialis

TWO-STRIPED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus bivittatus

RED-LEGGED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus femurrubrum

Protein-rich grasshoppers are an important late-summer, early-fall food source for birds. The absence of these insects has forced many species of breeding birds to abandon farmland or, in some cases, disappear altogether.

To pass the afternoon, we sat quietly along the edge of a pond created recently by North American Beavers (Castor canadensis). They first constructed their dam on this small stream about five years ago. Since then, a flourishing wetland has become established. Have a look.

Isn’t that amazing? North American Beavers build and maintain what human engineers struggle to master—dams and ponds that reduce pollution, allow fish passage, and support self-sustaining ecosystems. Want to clean up the streams and floodplains of your local watershed? Let the beavers do the job!

We’ve got the summertime blues for you, right here at susquehannawildlife.net…

…so don’t let the summertime blues get you down. Grab a pair of binoculars and/or a camera and go for a stroll!

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

Visitors stopping by Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area this week found yet another post-breeding wanderer feeding in the shallows of the main lake and adjacent pond along Hopeland Road—a juvenile Little Blue Heron.

The juvenile Little Blue Heron is a white bird resembling an egret during its first year. At about one year of age, it begins molt into a deep blue adult plumage. Young birds are notorious for roaming inland and north from breeding areas along the Atlantic coast and throughout the south. They are a post-breeding wanderer nowhere near as rare as the Limpkin seen at Middle Creek a week ago; a few are found each summer in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

As oft times happens, birders attracted to see one unusual bird find another in the vicinity. So with fall shorebird migration ramping up, the discovery of something out of the ordinary isn’t a total surprise, particularly where habitat is good and people are watching.

The arrival of a Hudsonian Godwit is not an unheard of occurrence in the lower Susquehanna region, but locating one that sticks around and provides abundant viewing opportunities is a rarity. This adult presumably left the species’ breeding areas in Alaska or central/western Canada in recent weeks to begin its southbound movement. Hudsonian Godwits pass through the eastern United States only during the autumn migration, and the majority fly by without being noticed along a route that mostly takes them offshore of the Mid-Atlantic States.

Mid-summer can be a less than exciting time for those who like to observe wild birds. The songs of spring gradually grow silent as young birds leave the nest and preoccupy their parents with the chore of gathering enough food to satisfy their ballooning appetites. To avoid predators, roving families of many species remain hidden and as inconspicuous as possible while the young birds learn how to find food and handle the dangers of the world.

But all is not lost. There are two opportunities for seeing unique birds during the hot and humid days of July.

First, many shorebirds such as sandpipers, plovers, dowitchers, and godwits begin moving south from breeding grounds in Canada. That’s right, fall migration starts during the first days of summer, right where spring migration left off. The earliest arrivals are primarily birds that for one reason on another (age, weather, food availability) did not nest this year. These individuals will be followed by birds that completed their breeding cycles early or experienced nest failures. Finally, adults and juveniles from successful nests are on their way to the wintering grounds, extending the movement into the months we more traditionally start to associate with fall migration—late August into October.

For those of you who find identifying shorebirds more of a labor than a pleasure, I get it. For you, July can bring a special treat—post-breeding wanderers. Post-breeding wanderers are birds we find roaming in directions other than south during the summer months, after the nesting cycle is complete. This behavior is known as “post-breeding dispersal”. Even though we often have no way of telling for sure that a wandering bird did indeed begin its roving journey after either being a parent or a fledgling during the preceding nesting season, the term post-breeding wanderer still applies. It’s a title based more on a bird sighting and it’s time and place than upon the life cycle of the bird(s) being observed. Post-breeding wanderers are often southern species that show up hundreds of miles outside there usual range, sometimes traveling in groups and lingering in an adopted area until the cooler weather of fall finally prompts them to go back home. Many are birds associated with aquatic habitats such as shores, marshes, and rivers, so water levels and their impact on the birds’ food supplies within their home range may be the motivation for some of these movements. What makes post-breeding wanderers a favorite among many birders is their pop. They are often some of our largest, most colorful, or most sought-after species. Birds such as herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, stilts, avocets, terns, and raptors are showy and attract a crowd.

While it’s often impossible to predict exactly which species, if any, will disperse from their typical breeding range in a significant way during a given year, some seem to roam with regularity. Perhaps the most consistent and certainly the earliest post-breeding wanderer to visit our region is the “Florida Bald Eagle”. Bald Eagles nest in “The Sunshine State” beginning in the fall, so by early spring, many of their young are on their own. By mid-spring, many of these eagles begin cruising north, some passing into the lower Susquehanna valley and beyond. Gatherings of dozens of adult Bald Eagles at Conowingo Dam during April and May, while our local adults are nesting and after the wintering birds have gone north, probably include numerous post-breeding wanderers from Florida and other Gulf Coast States.

So this week, what exactly was it that prompted hundreds of birders to travel to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area from all over the Mid-Atlantic States and from as far away as Colorado?

Was it the majestic Great Blue Herons and playful Killdeer?

Was it the colorful Green Herons?

Was it the Great Egrets snapping small fish from the shallows?

Was it the small flocks of shorebirds like these Least Sandpipers beginning to trickle south from Canada?

All very nice, but not the inspiration for traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles to see a bird.

It was the appearance of this very rare post-breeding wanderer…

…Pennsylvania’s first record of a Limpkin, a tropical wading bird native to Florida, the Caribbean Islands, and South America. Many observers visiting Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area had never seen one before, so if they happen to be a “lister”, a birder who keeps a tally of the wild bird species they’ve seen, this Limpkin was a “lifer”.

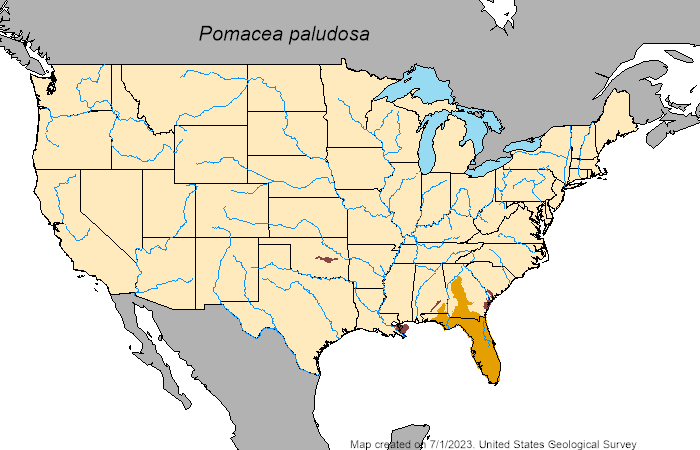

The Limpkin is an inhabitant of vegetated marshlands where it feeds almost exclusively upon large snails of the family Ampullariidae, including the Florida Applesnail (Pomacea paludosa), the largest native freshwater snail in the United States.

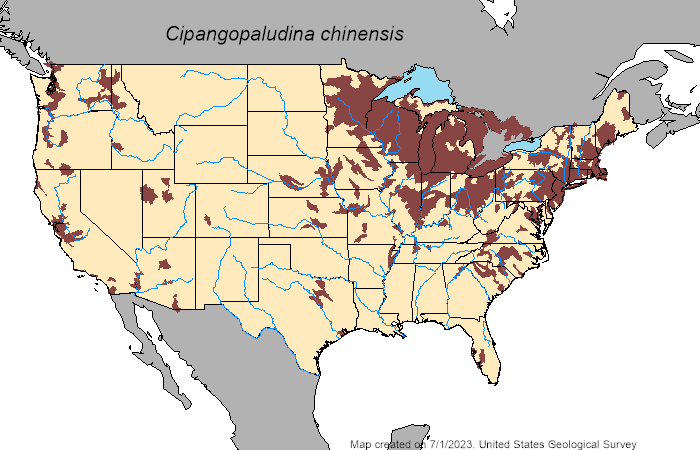

Observations of the Limpkin lingering at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area have revealed a pair of interesting facts. First, in the absence of Florida Applesnails, this particular Limpkin has found a substitute food source, the non-native Chinese Mystery Snail (Cipangopaludina chinensis). And second, Chinese Mystery Snails have recently become established in the lakes, pools, and ponds at the refuge, very likely arriving as stowaways on Spatterdock (Nuphar advena) and/or American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea), native transplants brought in during recent years to improve wetland habitat and process the abundance of nutrients (including waterfowl waste) in the water.

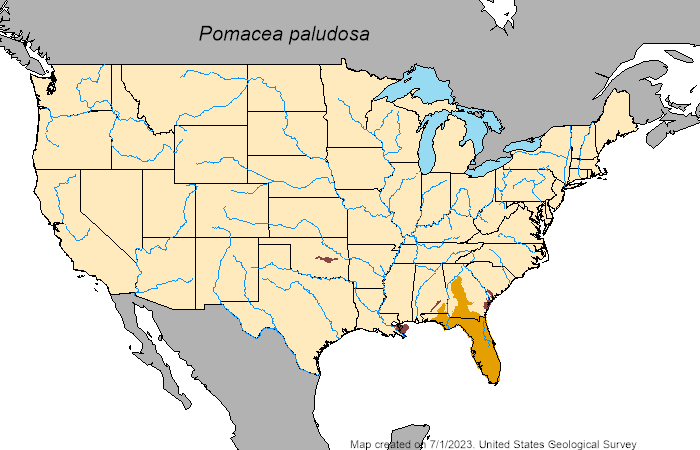

The Middle Creek Limpkin’s affinity for Chinese Mystery Snails may help explain how it was able to find its way to Pennsylvania in apparent good health. Look again at the map showing the range of the Limpkin’s primary native food source, the Florida Applesnail. Note that there are established populations (shown in brown) where these snails were introduced along the northern coast of Georgia and southern coast of South Carolina…

…now look at the latest U.S.G.S. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species map showing the ranges (in brown) of established populations of non-native Chinese Mystery Snails…

…and now imagine that you’re a happy-go-lucky Limpkin working your way up the Atlantic Coastal Plain toward Pennsylvania and taking advantage of the abundance of food and sunshine that summer brings to the northern latitudes. It’s a new frontier. Introduced populations of Chinese Mystery Snails are like having a Waffle House serving escargot at every exit along the way!

Be sure to click the “Freshwater Snails” tab at the top of this page to learn more about the Chinese Mystery Snail and its arrival in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Once there, you’ll find some additional commentary about the Limpkin and the likelihood of Everglade Snail Kites taking advantage of the presence of Chinese Mystery Snails to wander north. Be certain to check it out.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY ELEVEN—May 31, 1983

“AOK Camp, Texas — 7 Miles S. of Kingsville”

“Went south to the 1st rest stop south of Sarita — No Tropical Parula. Lots of other birds. We added Summer Tanager and Lesser Goldfinch.”

The Sarita Rest Area along Route 77 was like a little oasis of taller trees in the Texas scrubland. We received reports from the birders we met yesterday at Falcon Dam that recently, Tropical Parula had been seen there. We searched the small area and listened carefully, but to no avail. For these warblers, nesting season was over. We were surprised to find Lesser Goldfinches in the trees. Back in 1983, the coastal plain of Texas was pretty far east for the species. Steve was a bit skeptical when we first spotted them, but once they came into plain view, he was a believer. I recall him finally exclaiming, “They are Lesser Goldfinches.” Summer Tanager was another wonderful surprise. Today, the Sarita Rest Area remains a stopping point for birders in south Texas. Both Lesser Goldfinch and Tropical Parula were seen there this spring.

After our roll of dice at the Sarita Rest Area, we continued south through the King Ranch en route back to Brownsville.

“Saw a Coyote on the way.”

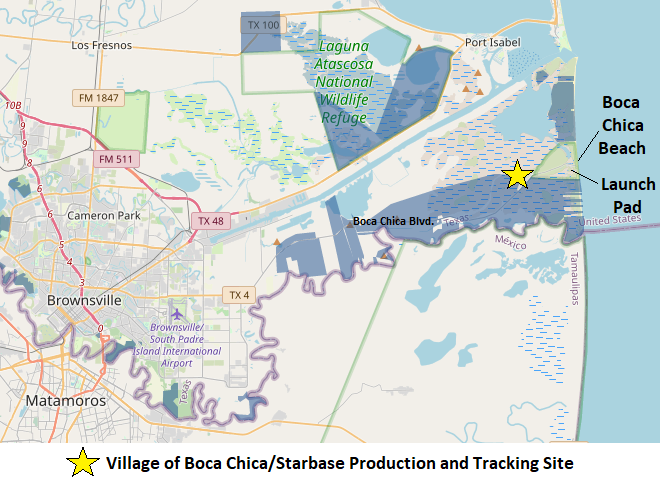

“Took Steve to the airport and drove out to Boca Chica where Harold went swimming.”

The drive from Brownsville out Boca Chica Boulevard to the Gulf of Mexico passes through about 18 miles of the outermost flats of the river delta that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley. This area is of course susceptible to the greatest impacts from tropical weather, especially hurricanes. During our visit, we passed a small cluster of ranch houses about two or three miles from the beach. This was the village known as Boca Chica. Otherwise, the area was desolate and left to the impacts of the weather and to the wildlife.

The mouth of the Rio Grande, and thus the international border with Mexico, was and still is about two miles south of Boca Chica Beach. Before the construction of dams and other flood control measures on the river, the path of the Rio Grande through the alluvium deposits on this outer section of delta would vary greatly. Accumulations of eroded material, river flooding, tides, and storms would conspire to change the landscape prompting the river to seek the path of least resistance and change its course. Surrounding the segments of abandoned channel, these changes leave behind valuable wetlands including not only the resacas of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, but similar features in tidal sections of the outer delta. When left to function in their natural state, deltas manage silt and pollutants in the waters that pass through them using ancient physical, biological, and chemical processes that require no intervention from man.

Harold was determined to go for a swim in the Gulf of Mexico before boarding a flight home. We all liked the beach. Why not? You may remember trips to the shore in the summertime. Back in the pre-casino days, we used to go to Atlantic City, New Jersey, to visit Steel Pier. For the first three quarters of the twentieth century, Steel Pier was the Jersey Shore’s amusement park at sea. There were rides, food stands, arcades, daily concerts with big name acts, diving shows, and ballroom dances.

There were, back then, attractions at Steel Pier that were creatively promoted to give the visitor the impression that they were going to see something more profound or amazing than was was delivered. You know, things advertised to draw you in, but its not quite what you expected.

For example, there was an arcade game promising to show you a chicken playing baseball. Okay, I’ll bite. Turns out the chicken did too. You put your money in the machine and watched as the chicken came out and rounded the diamond eating poultry food as it was offered at each of the bases. Hmmm…to suggest that this was a chicken playing baseball seems like a bit of a stretch.

They had a diving bell there too. Wow! We’ll go below the waves and view the fish, octopi, and other sights through the water-tight windows while we descend to the ocean floor. You would pay to get inside, then they would lower the bell down through a hole in the pier. Once below the rolling surf, you would get to look at the turbid seawater sloshing around at the window like dirty suds in a washing machine. If you were lucky, some trash might briefly get stuck on the glass. To imply that this was a chance to see life beneath waves was B. S., and I don’t mean bathysphere.

Then there was a girl riding a diving horse. You would hike all the way to the end of the pier and watch the preliminary show with these divers plunging through a hole in the deck and into the choppy Atlantic below. They were very good, but no, we never saw Rodney Dangerfield do a “Triple Lindy” there. And then it was time for the finale. Wow, is that horse going to dive in the ocean? How do they get the horse back up on the pier? Forget it. Instead of that, they walked poor Mr. Ed up a ramp into a box, then the girl climbs on his back, the door opens, and she nudges Ol’ Ed to into a plunge followed by a thumping splash into a swimming pool on the deck. Not bad, but not what we were expecting. Since we had to walk almost a quarter of a mile out to sea to get there, they kinda led us to believe that the amazing equine was going to leap into the Atlantic—horse hockey!

Preceding all this fun was a guy back in the early 1930s, William Swan, who, in June 1931, flew a “rocket-powered plane” at Bader Field outside Atlantic City. The plane was actually a glider on which a rocket was fired producing about 50 pounds of thrust to boost it airborne after assistants got it rolling by pushing it. In newspaper articles and on newsreels afterward, he would promote the future of rocket planes carrying passengers across the ocean at 500 miles per hour. Using a glider equipped with pontoons for landing in the ocean, he promised to make several flights daily from Steel Pier. Those who came to see him may have, at best, watched him fire small rockets he had attached to his craft—little more.

What does all this have to do with Boca Chica Beach? It turn out two years later, William Swan is hyping a new innovation—a rocket-powered backpack. He’d demonstrate it during a skydiving exhibition at the Del-Mar Beach Resort, a cluster of 20 cabins and community buildings on Boca Chica Beach. According to his deceptive promotions, Swan would jump out of a plane and light flares as he fell. Then he’d ignite the backpack rocket and land on the shoreline in front of the crowd. The event was expected to draw 3,000 carloads of people. When the big day came, just over 1,000 cars showed up. The event was a bust and the weather was bad, cloudy with a mist over the gulf. During a break in the clouds, the pilot took Swan aloft. Swan ordered him out to sea and to 8,500 feet, a higher altitude than planned. Then he jumped. He dropped the flares, which didn’t then ignite, and neither did the rocket. He opened his chute at 6,000 feet and the crowd watched as Swan drifted into the mist offshore and was never seen again. There were rumors both that he used the stunt as a way to flee to Mexico to start a new life and that he had committed suicide. Others believed he died accidentally. To learn the full story of Billy Swan, check out The Rocketeer Who Never Was, by Mark Wade.

Forward fifty years to our visit to Boca Chica Beach. The Del-Mar Beach Resort, built in the 1920s as a cluster of 20 cabins and a ballroom, was gone. It was destroyed by a hurricane later in the same year Swan disappeared—1933. The resort, which was hoped would be the start of a seaside vacation city, never reopened. In 1983, we saw just a handful of beach goers and the birds, that’s it. One could look down to the south and see the area of the Rio Grande’s mouth and Mexico, but there were no structures of note. It was peaceful and alive with wildlife. We were sorry we didn’t have more time there.

“Here we added Least Tern, Brown Pelican and Sandwich Tern.”

Today, the Village of Boca Chica and Boca Chica Beach are the location of SpaceX’s South Texas Launch Facility. Those of the village’s ranch houses built in 1967 that have survived hurricane devastation over the years have been incorporated into the “Starbase” production and tracking facility. The launch pad and testing area is along the beach just behind the dunes at the end of Boca Chica Boulevard.

The latest launch, just more than a month ago, was the maiden flight of “Starship”, a 394-foot behemoth that is the largest rocket ever flown. The “Super Heavy Booster” first stage’s 33 Raptor engines produce 17.1 million pounds of thrust making Starship the most powerful rocket ever flown. See, things really are bigger in Texas.

Last month’s unmanned orbital test launch ended when the Starship spacecraft failed to separate at staging. As the booster section commenced its roll manuever to return to the launch pad, the entire assembly began tumbling out of control. It exploded and rained debris into the gulf along a stretch of the downrange trajectory.

Development of Starbase is opposed by many due to noise, safety, and environmental concerns. Boca Chica Boulevard (Texas Route 4) is frequently closed due to activity at the launch pad site, thus excluding residents and tourists from visiting the beach. With over 1,200 people already working at Starbase, demand for housing in the Brownsville area has increased. Some have accused SpaceX CEO Elon Musk of promoting gentrification of the area—running up housing prices to force out the lower-income residents. He has responded with a vision of a new city at Boca Chica, his “space port”.

Does history have an applicable lesson for us here? When Musk talks about going to the Moon and Mars, or ferrying a hundred people around the world on his Starship, is it just another Steel Pier-style deception? Is Musk a modern-day William Swan? A very talented marketer? Could be. And is the whole thing setting up a large-scale replay of the Del-Mar Beach Resort’s demise in 1933? Is building a city on the outer edges of a river delta asking for an outcome similar to the one suffered by New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina? It’s likely. After all, building on or near a beach, floodplain, or delta is a short-sighted venture to begin with. If the party doing the developing doesn’t suffer the consequences of defying the laws of nature, one of the poor suckers in the successive line of buyers and occupants will. This isn’t rocket science folks. Its weather, climate, and erosion, and its been altering coastlines, river courses, and the composition and distribution of life forms on this planet for millions of years. And guess what. These factors will continue to alter Earth for millions of years more after man the meddler is long gone. You’re not going to stop their effects, and you’re not going to escape their wrath by ignoring them. So if you’re smart, you’ll get out of their way and stay there!

Billy Swan was probably broke when he came to Boca Chica. He reportedly borrowed 20 bucks from the resort operator just to cover his personal expenses during his backpack rocket event. Elon Musk comes to Boca Chica with over 100 billion dollars and capital from other private investors to boot. Despite some obvious exaggerations about colonizing the Moon, Mars, and other celestial bodies, he just might be able to at least get people there for short-term visits. And that’s quite an accomplishment.

“Then took Harold to the airport. We left him at 3:30 and headed north on Route 77, got as far as Victoria. Had a flat on the way. Larry had the spare on in 10 minutes. We stopped at a picnic area for the nite, because we could not find the camping area.”

If we were going to have a flat, we had it at the right place. We were just outside Raymondville, Texas, at a newly constructed highway interchange. The wide, level shoulder allowed us to get the camper off to the side of the road in a safe place to jack it up and change the tire. Easy. We were thereafter homeward bound.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY TEN—May 30, 1983

“Falcon Dam State Park, Texas”

“9:30 — Breakfast — The Pauraque sang all nite and the Mockingbird sang half the nite and interrupted my sleep.”

Before leaving the campground, we paid a final visit to the shores of the reservoir. We saw Anhinga and Little Blue Heron among the other water birds we had seen there previously.

“Now to the spillway again. We got lucky — A Green Kingfisher flew in and gave us great views. Cliff Swallows were plentiful. The Green Herons were fishing and so was a Kiskadee Flycatcher. Black Vultures were flying around. A Groove-billed Ani was very much in evidence.”

The little Green Kingfisher (Chloroceryle americana), after all the effort we finally saw one. It was just half the size of the Ringed Kingfisher we saw at the spillway one day earlier.

“Here we met Bill Graber from San Antonio. Ron and 3 women—Sandra from Wales, 1 from Oregon, and 1 from San Antonio… We all walked to the spot for the Ferruginous Owl”

We again followed Father Tom’s directions; “Park at spillway, walk the road to a fence, go right to the river, follow fence to a big dip (gully).”

Once in the designated area, several of us began searching around the vicinity for the owls. I was out of sight of the others and was examining a long procession of tropical leafcutter ants, possibly the Texas Leafcutter Ant (Atta texana). Their foraging trail had two single-file lanes—worker ants carrying dime-sized pieces of leaves to the nest and worker ants returning to the tree to harvest more. The ants’ path of travel stretched for more than one hundred feet down the limbs and trunk of the source tree, across the sandy ground, over a fallen log, across more sandy ground, through some leaf litter in the shrubs, and to the nest, where the foliage will be used to cultivate fungi (Lepiotaceae) for food. Thousands of worker ants were marching the route while others guarded their lines—fascinating.

Suddenly, I heard a commotion in the brush. Collared Peccaries (Dicotyles tajacu), also known as Javelina, on the run and headed right my way! The others must have unknowingly spooked them. In an instant I scrambled to my feet and bounded up the trunk of a willow tree that was strongly arching toward the river and had partially fallen after the bank had washed away. There I stood atop the nearly horizontal trunk as between 6 and 10 grunting peccaries bustled past in a cloud of dust. Just as fast as they had appeared, they were gone.

I walked back toward the gully and as I approached, I could see everyone peering at something in the dense foliage of the trees overhanging the river.

“…eventually Sandra spotted one coming in. Another was also seen in a much better position. We all saw the 2 black spots on the back of his head when he turned his head 180°. It looked like another face.”

They had found the Ferruginous Pygmy Owls, right where Father Tom said they would be. But they weren’t easy to see. And they were tiny. Make a loose fist—that’s about the size of a Ferruginous Pygmy Owl. We had to take turns standing at favorable places where there was a less-obstructed view of each bird. I’m not certain that anyone was able to get photographs. The shade was too dark for my equipment to get a favorable exposure. Such had been the case for many of the birds we found in the riparian forest. This owl was a life list species for everyone in our group and for most of the others. Like the Green Kingfisher, the owls were just barely within the A.B.A. area, on limbs stretching out above the waters of the Rio Grande.

“Then we came back to the picnic ground and walked the river’s edge for a 1/4 mile — Nothing extra, except an Altamira Oriole.”

I again did a little wading in the Rio Grande to cool down after spending hours in the hot scrubland/forest.

“On the way back to Brownsville, we stopped at Santa Margarita again with no Brown Jay luck.”

Though we never did bump into the roving band of Brown Jays at Santa Margarita Ranch, they were there, and they’re a species that’s still there today.

“On to Brownsville for good sightings of the Clay-colored Robin at the radio station.”

We returned to the radio transmitter site at Coria and Los Ebanos in Brownsville for yet another attempt to find Clay-colored Robins/Thrushes. After again securing permission from Mr. Wilson to have a look around, we at last had success and found a pair of Clay-colored Thrushes moving about in the boughs of the shade-casting tress and shrubs. With some persistence, we all got binocular views of these earth-tone rarities from Mexico.

While in Brownsville, we thought it a good idea to dabble a bit in the experiences of local consumer culture, so we drove downtown. After finding a place to park the camper, we commenced to going for an international stroll over the bridge that crosses the Rio Grande into Matamoras, Tamaulipas, Mexico. It was our first legal incursion south of the border. (In recent days, we may have stepped back-and-forth over the line a couple of times while wading in the river below Falcon Dam.)

Once in Matamoros, we entered the bank. Steve wanted to get some Mexican currency and coins for his collection, so we stepped inside. It was a typical classical-style masonry building like most banks built early in the twentieth century were, but this one had very few accoutrements inside. There was a big vault, some cash drawers, maybe a desk and a chair, and that was it. The doors were left open to get a flow of dirty air in the place because there was no air conditioning. No loan department or Christmas Clubs here, just dollars for pesos.

Upon leaving the bank and heading into the town, we were solicited by the unlicensed curbside pharmacists selling herbs and other home remedies. Not for me, I had one thing in mind on this shopping trip.

We walked up the street to step inside some of the numerous tourist shops—stuff everywhere. The other men bought a few post cards. For a friend back home, I bought a key chain with a tiny pair of cowboy boots attached. Having heard that cowboy boots could be had for cheap south of the border, he had given me his size requirements and asked that I should get him a pair if the price was right. Well, the price wasn’t that great in the tourist town section of the city, so I got him the key chain instead.

After about an hour, we were headed back over the bridge into Brownsville. Along the pedestrian walkway, there was a United States Customs checkpoint one had to pass before entering the country. The customs officer asked the usual questions and after telling him we were only in Mexico for an hour, he queried, “Did you buy anything that you’re bringing back into the country.” Having an item to declare, I told him yes, I bought a pair of cowboy boots. He looked down at my rubber-toed canvas sneakers, then looked at Russ, Harold, and Steve, who obviously weren’t carrying or wearing boots, and he snapped, “Where are they?” I pulled the wax paper bag with the key chain inside from my pocket. He called me a smart ass and waved us on. We chuckled.

The only bird species seen during or short trek into Matamoros? House Sparrow.

In the forty years since our visit to the Rio Grande Valley, the rate of northbound human migration across the river, and particularly the amount of smuggling activity that uses the migration as a diversion to cover its operations, has surely taken the fun out of being on the border. Many of the places we visited are no longer open to the public, or access is restricted and subject to tightened security. Santa Margarita Ranch, for example, now allows guided tours only. Falcon Dam changed its security practices after one of a pair of opposing drug cartels escalated their mutual dispute by planting explosives there—threatening to blow it up to hamper crossings by its opponent’s smugglers in the fordable waters downstream.

Fortunately for today’s birder, many of the tropical specialties have inched their range north of the Rio Grande’s banks and can be found on accessible public and private lands outside the immediate tension zone. National Wildlife Refuges and Texas State Parks provide access to some of the best habitats. Places like the King Ranch even offer guided bird and wildlife tours on portions of their vast holdings where many border species including Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, Crested Caracara (Caracara plancus), Green Jay, Vermillion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus obscurus), Northern Beardless-Tyrannulet (Camptostoma imberbe), and the tropical orioles are now found. So don’t let the state of dysfunction on the border stop you from visiting south Texas and its marvelous ecosystems. It’s still a birder’s paradise!

“We ate supper at Luby’s Cafeteria and headed north on Route 77 for the Tropical Parula.”

Harold was very pleased to have added Hook-billed Kite, Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, and Clay-colored Thrush to his A.B.A. life list, so he offered to buy dinner. After visiting a mail box to get a few postcards on their way, we ate at Luby’s Cafeteria in Brownsville, which was an interesting experience for that time period. Luby’s was a regional restaurant chain. You could get in line there and select anything you wanted, then pay for it by the item. Luby’s predated the all-you-can-eat salad bar and buffet craze that would sweep the restaurant industry in coming years. Under the circumstances, it was perfect for us. After not eating much all week due to the hot, humid conditions that accompanied the unusually rainy weather, our appetites begged satisfaction—but the heat hadn’t relented, so we didn’t want to overdo it. The staff at Luby’s didn’t blink an eye at us entering the restaurant wearing field clothes. It was the first climate-controlled space we had enjoyed all week—very refreshing. We really enjoyed the experience and it recharged us all.

Near Raymondville along Route 77, a set of electric wires strung on tall wooden poles paralleled the highway. These poles were hundreds of yards away from road, but seeing a raptor atop one, we stopped and got out the spotting scope. It was yet another south Texas specialty, a White-tailed Hawk (Buteo albicaudalus), a bird of grassland and brush. Its range north of Mexico is limited to an area of Texas from the Lower Rio Grande Valley north through the King Ranch to just beyond Kingsville. A short while later, we saw one or two more on our way through the King Ranch.

“Saw a flock of White-rumped Sandpipers when we stopped for gas.”

Lest one might think that traveling through parts of five south Texas counties to go from Falcon Dam back east through the Lower Rio Grande Valley to Brownsville and then north for a return stay at the A.O.K. campground is just another day of birding punctuated by some driving every now and again, consider the mileage racked up on the odometer today—259 miles. Even the counties are bigger in Texas.

We topped off the fuel tank at a service station near Sarita, Texas, and saw the White-rumped Sandpipers (Calidris fuscicollis) in a pool of rainwater among the scrubland at roadside.

“We stopped at the AOK Camp Ground 7 miles south of Kingsville and will return to get the parula at the first rest stop south of Sarita. Now 9:30 CDST.”

WHY WORRY ABOUT SPIDERS AND SNAKES?

Back at the old A.O.K. campground, this time with Harold and Steve, we decided to have a camp fire for the first time on the trip. We bought a bundle of wood at the camp office and soon had it crackling. I broke out the harmonica, but knowing no cowboy tunes, soon stashed it away. We had better things to do. Did we bake some beans in an iron kettle on the hot embers? No, we ate plenty at Luby’s. Did we toast marshmallows on sticks and make s’mores? Nope. Did we roast our weenies and warm our buns? No, not that either. We simply sat around recapping our trip while scratching our itchy ankles. Seems each of us was hosting chigger larvae and these parasites, upon maturing to nymphs and departing, left irritating wounds in our skin where they had been feeding—right in the hollow of our ankles.

Chiggers (Trombiculidae), like spiders and ticks, are arachnids. They thrive in humid environments as opposed to arid climes. Our best guess was that we had picked them up while hiking around in the subtropical riparian forests along the Rio Grande in the early days of the trip. My wounds eventually left little red pimples where each tiny larva had been feeding. They healed about a week after I got home. Due to the severity of his wounds, Steve cancelled a second week of his trip. On his own, he was going to continue west along the Rio Grande to the area of Big Bend National Park, but instead booked a flight home. Chigger larvae are stealthy little sneaks—we never had any clue they got us until they were gone. So why worry about spiders and snakes?

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY THREE—May 23, 1983

For Russ, Harold, and Steve, this trip would target several bird species each individual had never observed at any prior time in their lives. Upon seeing a new bird, they could add it to their personal “life list”. They, like thousands of other “listers”, were dedicated to the goal of having a life list that included over 600 species seen in the American Birding Association (A.B.A.) area—North America north of Mexico. Harold had traveled throughout much of North America (and the world) and had an A.B.A. life list well in excess of 600 species, thus he had seen nearly all of the regularly occurring birds in the coverage area. His chance for seeing new species was limited to vagrants that might wander into North America or tropical birds that, over time, had extended their range north of Mexico into the United States. I don’t recall how many species Russ and Steve had seen, but I know each had very few opportunities for new finds east of the Rocky Mountains. For all three of these men, the Lower Rio Grande Valley presented a best bet to add multiple species to their lists. I had never been south of Cape Hatteras or west of Pennsylvania, so I had the opportunity to add dozens of species to a life list. Throughout the trip, Russ, Harold, and Steve enthusiastically helped me locate and see new species. As a result, I saw over 50 new birds to add to my list.

One of the functions of the American Birding Association was to decide which bird species an observer could add to the life list. The official A.B.A. list was revised regularly to include not only regularly occurring native species, but vagrants as well. One of the trickier determinations was the status of introduced species. Back in 1983, a birder could count a Ring-necked Pheasant seen in Pennsylvania on their A.B.A. life list because they were thought to be freely reproducing with a population sustainably established in the state. Today, they are considered an exotic release and are not countable under A.B.A. rules.

Enter the Black Francolin (Francolinus francolinus), a member of the pheasant family that back in 1983, was countable under A.B.A. rules. Native to India, the Black Francolin was introduced into southwest Louisiana in 1961 and was apparently reproducing and established. Russ had a tip that they were seen with some regularity in areas of farmland, marsh, and oil fields south of Vinton, Louisiana. It was one of this trip’s target species for his life list.

“Ready for Black Francolin. Up at 5:30 — After breakfast, we went to Gum Cove Road. No Francolins, but at the end of the blacktop road, we had 5 Purple Gallinules in the scope at one time. King Rails were plentiful. We found a dead male Painted Bunting. Later, we saw a very beautiful live one. Water everywhere. Flooded fields everywhere. The road was flooded for about 50 yards at one point. White Ibis were abundant.”

Other sightings of note along Gum Cove Road included: Northern Bobwhite, Common Nighthawk, Cattle Egret, Green Heron, American Bittern, Snowy Egret, Glossy Ibis, Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus), Forster’s Tern, Black Tern, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Eastern Kingbird, Purple Martin, Barn Swallow, Brown Thrasher, Loggerhead Shrike, Red-winged Blackbird, Brown-headed Cowbird, Eastern Meadowlark, Boat-tailed Grackle (Quiscalus major), and Great-tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus)—a very large and noisy blackbird I had never seen before.

The reader may be interested to know that today, the area between Vinton and the Gulf of Mexico has largely been surrendered to the forces of the hurricanes that strike the region with some regularity. Cameron Parish* is a sparsely populated buffer zone of marshes, abundant wildlife, and oil and gas wells. Its population of more than 9,000 in 1983 has plunged to less than 6,000 today. Hurricane Rita (2005) and Hurricane Ike (2008) precipitated the sharp decline. The latter hurricane had a 22-foot storm surge that flooded areas 60 miles inland of the coastline. Following these storms, the majority of severely damaged and destroyed homes were not rebuilt and residents in the most affected areas relocated. In 2020, Hurricane Laura made landfall at Cameron Parish with record-tying 150 mph winds and a storm surge that pushed flood waters inland to Lake Charles. Six weeks later, Hurricane Delta followed with 100 mph winds. For government agencies, the emergency response required by these two storms was minimized by the reduced presence of people and/or their personal property.

* A parish in Louisiana is similar to a county in other states.

“After a quick stop at the camp grounds, where I slipped and fell in the shower last nite, we headed south. Larry saw many birds en route.”

Russ took a bad fall on a slippery wet concrete floor and had bruises to show for it. It worried me; he was 71 years old at the time. But he was adamant about continuing on and did so with great vigor.

Just hours after a sojourn through the swampy parcels south of Vinton, we were cruising through the metropolis of Houston, Texas, then across a landscape with less cultivated cropland and more scrubland with grazing. Here and there, but primarily to the east of Houston, blankets of roadside wildflowers painted the landscape with eye-popping color. Lady Bird Johnson encouraged the plantings soon after she and Lyndon returned to Texas upon leaving life in the White House in 1969. The sight of those vivid blooms was so memorable and so beautiful. One couldn’t resist making nasty comparisons to the gobs of mowed grass and mangled trash along the highways back in Pennsylvania.

Birds along the way: Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Common Nighthawk, Black-bellied Whistling Duck, Yellow-crowned Night Heron, Great Blue, Heron, Great Egret, Black Vulture, Turkey Vulture, Red-tailed Hawk, Laughing Gull, Black Tern, Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Cliff Swallow, Loggerhead Shrike, and Painted Bunting. I saw my first Black-bellied Whistling Ducks (Dendrocygna autumnalis) and Golden-fronted Woodpecker (Melanerpes aurifrons) near Woodsboro, Texas, and added both to my life list.

“We stopped for the nite at an A OK camp ground 7 miles south of Kingsville.”

Birds at the camp included two Black-bellied Whistling Ducks flying overhead, Common Nighthawk, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Blue Grosbeak, and another “lifer”—Curve-billed Thrasher (Toxostoma curvirostre).

We also saw a Mexican Ground Squirrel (Ictidomys mexicanus), easily identified by the rows of white spots running the length of its back.

While relaxing at the campsite that evening, we watched the landscape darken and remarked how interesting it was that the glowing red sun had yet to set below the distant horizon—a land so very flat and air so hazy and humid.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY TWO—May 22, 1983

Our goal today was to continue traveling and reach western Louisiana.

“We were on our way at 6:08. Stopped for a quick lunch in the camper and drove to Vinton, Louisiana, KOA. Lots of hard rain through Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama.

As we crossed Mississippi and entered Louisiana, we left the rain and the Appalachians behind. Upon crossing the Mississippi River, we had arrived in the West Gulf Coastal Plain, the physiographic province that extends all the way south along the Texas coast to Mexico and includes the Lower Rio Grande Valley. West of Baton Rouge, we began seeing waders in the picturesque Bald Cypress swamps—Great Egrets, Green Herons (Butorides virescens), Little Blue Herons (Egretta caerulea), and Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) were identified. A Pileated Woodpecker was observed as it flew above the roadside treetops.

The rains we endured earlier in the trip had left there mark in much of Louisiana and Texas. Flooding in agricultural fields was widespread and the flat landscape often appeared inundated as far as the eye could see. Along the highway near Vinton, we spotted the first two of the many southern specialties we would find on the trip, a Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) and a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (Tyrannus forficatus), both perched on utility wires and searching for a meal.

This linear grove of mature trees, many of them nearly one hundred years old, is a planting of native White Oaks (Quercus alba) and Swamp White Oaks (Quercus bicolor).

Imagine the benefit of trees like this along that section of stream you’re mowing or grazing right now. The Swamp White Oak in particular thrives in wet soils and is available now for just a couple of bucks per tree from several of the lower Susquehanna’s County Conservation District Tree Sales. These and other trees and shrubs planted along creeks and rivers to create a riparian buffer help reduce sediment and nutrient pollution. In addition, these vegetated borders protect against soil erosion, they provide shade to otherwise sun-scorched waters, and they provide essential wildlife habitat. What’s not to love?

The following native species make great companions for Swamp White Oaks in a lowland setting and are available at bargain prices from one or more of the County Conservation District Tree Sales now underway…

So don’t mow, do something positive and plant a buffer!

Act now to order your plants because deadlines are approaching fast. For links to the County Conservation District Tree Sales in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, see our February 18th post.

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

Meet the Double-crested Cormorant, a strangely handsome bird with a special talent for catching fish. You see, cormorants are superb swimmers when under water—using their webbed feet to propel and maneuver themselves with exceptional speed in pursuit of prey.

Double-crested Cormorants, hundreds of them, are presently gathered along with several other species of piscivorous (fish-eating) birds on the lower Susquehanna River below Conowingo Dam near Rising Sun, Maryland. Fish are coming up the river and these birds are taking advantage of their concentrations on the downstream side of the impoundment to provide food to fuel their migration or, in some cases, to feed their young.

In addition to the birds, the movements of fish attract larger fish, and even larger fishermen.

The excitement starts when the sirens start to wail and the red lights begin flashing. Yes friends, it’s showtime.

Within minutes of the renewed flow, birds are catching fish.

Then the anglers along the wave-washed shoreline began catching fish too.

The arrival of migrating Hickory Shad heralds the start of a movement that will soon include White Perch, anadromous American Shad, and dozens of other fish species that swim upstream during the springtime. Do visit Fisherman’s Park at Conowingo Dam to see this spectacle before it’s gone. The fish and birds have no time to waste, they’ll soon be moving on.

To reach Exelon’s Conowingo Fisherman’s Park from Rising Sun, Maryland, follow U.S. Route 1 south across the Conowingo Dam, then turn left onto Shuresville Road, then make a sharp left onto Shureslanding Road. Drive down the hill to the parking area along the river. The park’s address is 2569 Shureslanding Road, Darlington, Maryland.

A water release schedule for the Conowingo Dam can be obtained by calling Exelon Energy’s Conowingo Generation Hotline at 888-457-4076. The recording is updated daily at 5 P.M. to provide information for the following day.

And remember, the park can get crowded during the weekends, so consider a weekday visit.

This morning, the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed experienced remotely the effects of fire and ice.

At daybreak, the cold air mass that brought the first freeze of the season to northernmost New England gave us a taste of the cold with temperatures below 50 degrees throughout.

At sunrise, the cloudless sky had a peculiar overcast look with no warm glow on buildings, vegetation, and terrain. Soon, the sun was well above the horizon, yet there was still a sort of darkness across the landscape.

All that bright filtered sunlight was ideal for photographing butterflies along the Conewago Falls shoreline. Have a look.

A moderate breeze from the south placed a headwind into the face of migrants trying to wing their way to winter quarters. The urge to reach their destination overwhelmed any inclination a bird or insect may have had to stay put and try again another day.

Blue Jays were joined by increasing numbers of American Robins crossing the river in small groups to continue their migratory voyages. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and a handful of sandpipers headed down the river route. Other migrants today included a Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis), and a few Common Mergansers (Mergus merganser), House Finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), and Common Grackles (Quiscalus quiscula).

The afternoon belonged to the insects. The warm wind blew scores of Monarchs toward the north as they persistently flapped on a southwest heading. Many may have actually lost ground today. Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) and Cloudless Sulphur butterflies were observed battling their way south as well. All three of the common migrating dragonflies were seen: Common Green Darner (Anax junius), Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens), and Black Saddlebags (Tramea lacerata).

The warm weather and summer breeze are expected to continue as the rain and wind from Hurricane Nate, today striking coastal Alabama and Mississippi, progresses toward the Susquehanna River watershed during the coming forty-eight hours.

The Neotropical birds that raised their young in Canada and in the northern United States have now logged many miles on their journey to warmer climates for the coming winter. As their density decreases among the masses of migrating birds, a shift to species with a tolerance for the cooler winter weather of the temperate regions will be evident.

Though it is unusually warm for this late in September, the movement of diurnal migrants continues. This morning at Conewago Falls, five Broad-winged Hawks (Buteo platypterus) lifted from the forested hills to the east, then crossed the river to continue a excursion to the southwest which will eventually lead them and thousands of others that passed through Pennsylvania this week to wintering habitat in South America. Broad-winged Hawks often gather in large migrating groups which swarm in the rising air of thermal updrafts, then, after gaining substantial altitude, glide away to continue their trip. These ever-growing assemblages from all over eastern North America funnel into coastal Texas where they make a turn to south around the Gulf of Mexico, then continue on toward the tropics. In the coming weeks, a migration count at Corpus Christi in Texas could tally 100,000 or more Broad-winged Hawks in a single day as a large portion of the continental population passes by. You can track their movement and that of other diurnal raptors as recorded at sites located all over North America by visiting hawkcount.org on the internet. Check it out. You’ll be glad you did.

Nearly all of the other migrants seen today have a much shorter flight ahead of them. Red-bellied Woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus), Red-headed Woodpeckers (Melanerpes erythrocephalus), and Northern Flickers (Colaptes auratus) were on the move. Migrating American Robins (Turdus migratorius) crossed the river early in the day, possibly leftovers from an overnight flight of this primarily nocturnal migrant. The season’s first Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) arrived. American Goldfinches are easily detected by their calls as they pass overhead. Look carefully at the goldfinches visiting your feeder, the birds of summer are probably gone and are being replaced by migrants currently passing through.

By far, the most conspicuous migrant today was the Blue Jay. Hundreds were seen as they filtered out of the hardwood forests of the diabase ridge to cautiously cross the river and continue to the southwest. Groups of five to fifty birds would noisily congregate in trees along the river’s edge, then begin flying across the falls. Many wary jays abandoned their small crossing parties and turned back. Soon, they would try the trip again in a larger flock.

A look at this morning’s count reveals few Neotropical migrants. With the exception of the Broad-winged Hawks and warblers, the migratory species seen today will winter in a sub-tropical temperate climate, primarily in the southern United States, but often as far north as the lower Susquehanna River valley. The individual birds observed today will mostly continue to a winter home a bit further south. Those that will winter in the area of Conewago Falls will arrive in October and later.

The long-distance migrating insect so beloved among butterfly enthusiasts shows signs of improving numbers. Today, more than two dozen Monarchs were seen crossing the falls and slowly flapping and gliding their way to Mexico.