Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

During one of the interludes between yesterday’s series of thunderstorms and rain showers, we had a chance to visit a wooded picnic spot to devour a little snack. Having packed lite fare, there wasn’t enough to share. Fortunately, pest control wasn’t a concern. It was handled for us…

After enjoying our little luncheon and watching all the sideshows, it was time to cautiously make our way home,…

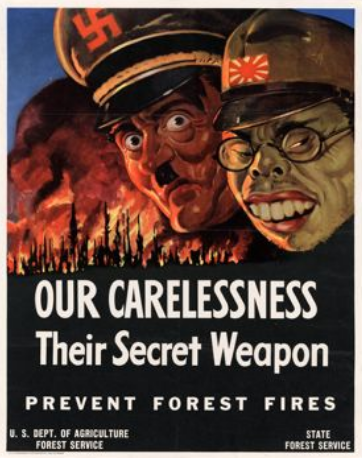

Homo sapiens owes much of its success as a species to an acquired knowledge of how to make, control, and utilize fire. Using fire to convert the energy stored in combustible materials into light and heat has enabled humankind to expand its range throughout the globe. Indeed, humans in their furless incomplete mammalian state may have never been able to expand their populations outside of tropical latitudes without mastery of fire. It is fire that has enabled man to exploit more of the earth’s resources than any other species. From cooking otherwise unpalatable foods to powering the modern industrial society, fire has set man apart from the rest of the natural world.

In our modern civilizations, we generally look at the unplanned outbreak of fire as a catastrophe requiring our immediate intercession. A building fire, for example, is extinguished as quickly as possible to save lives and property. And fires detected in fields, brush, and woodlands are promptly controlled to prevent their exponential growth. But has fire gone to our heads? Do we have an anthropocentric view of fire? Aren’t there naturally occurring fires that are essential to the health of some of the world’s ecosystems? And to our own safety? Indeed there are. And many species and the ecosystems they inhabit rely on the periodic occurrence of fire to maintain their health and vigor.

Man has been availed of the direct benefits of fire for possibly 40,000 years or more. Here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the earliest humans arrived as early as 12,000 years ago—already possessing skills for using fire. Native plants and animals on the other hand, have been part of the ever-changing mix of ecosystems found here for a much longer period of time—millions to tens of millions of years. Many terrestrial native species are adapted to the periodic occurrence of fire. Some, in fact, require it. Most upland ecosystems need an occasional dose of fire, usually ignited by lightning (though volcanism and incoming cosmic projectiles are rare possibilities), to regenerate vegetation, release nutrients, and maintain certain non-climax habitat types.

But much of our region has been deprived of natural-type fires since the time of the clearcutting of the virgin forests during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This absence of a natural fire cycle has contributed to degradation and/or elimination of many forest and non-forest habitats. Without fire, a dangerous stockpile of combustible debris has been collecting, season after season, in some areas for a hundred years or more. Lacking periodic fires or sufficient moisture to sustain prompt decomposition of dead material, wildlands can accumulate enough leaf litter, thatch, dry brush, tinder, and fallen wood to fuel monumentally large forest fires—fires similar to those recently engulfing some areas of the American west. So elimination of natural fire isn’t just a problem for native plants and animals, its a potential problem for humans as well.

To address the habitat ailments caused by a lack of natural fires, federal, state, and local conservation agencies are adopting the practice of “prescribed fire” as a treatment to restore ecosystem health. A prescribed fire is a controlled burn specifically planned to correct one or more vegetative management problems on a given parcel of land. In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is used to…

Let’s look at some examples of prescribed fire being implemented right here in our own neighborhood…

In Pennsylvania, state law provides landowners and crews conducting prescribed fire burns with reduced legal liability when the latter meet certain educational, planning, and operational requirements. This law may help encourage more widespread application of prescribed fire in the state’s forests and other ecosystems where essential periodic fire has been absent for so very long. Currently in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is most frequently being employed by state agencies on state lands—in particular, the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources on State Forests and the Pennsylvania Game Commission on State Game Lands. Prescribed fire is also part of the vegetation management plan at Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation and on the land holdings of the Hershey Trust. Visitors to the nearby Gettysburg National Military Park will also notice prescribed fire being used to maintain the grassland restorations there.

For crews administering prescribed fire burns, late March and early April are a busy time. The relative humidity is often at its lowest level of the year, so the probability of ignition of previous years’ growth is generally at its best. We visited with a crew administering a prescribed fire at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area last week. Have a look…

Prescribed burns aren’t a cure-all for what ails a troubled forest or other ecosystem, but they can be an effective remedy for deficiencies caused by a lack of periodic episodes of naturally occurring fire. They are an important option for modern foresters, wildlife managers, and other conservationists.

Only fools mess around with bees, wasps, and hornets as they collect nectar and go about their business while visiting flowering plants. Relentlessly curious predators and other trouble makers quickly learn that patterns of white, yellow, or orange contrasting with black are a warning that the pain and anguish of being zapped with a venomous sting awaits those who throw caution to the wind. Through the process of natural selection, many venomous and poisonous animals have developed conspicuously bright or contrasting color schemes to deter would-be predators and molesters from making such a big mistake.

Visual warnings enhance the effectiveness of the defensive measures possessed by venomous, poisonous, and distasteful creatures. Aggressors learn to associate the presence of these color patterns with the experience of pain and discomfort. Thereafter, they keep their distance to avoid any trouble. In return, the potential victims of this unsolicited aggression escape injury and retain their defenses for use against yet-to-be-enlightened pursuers. Thanks to their threatening appearance, the chances of survival are increased for these would-be victims without the need to risk death or injury while deploying their venomous stingers, poisonous compounds, or other defensive measures.

One shouldn’t be surprised to learn that over time, as these aforementioned venomous, poisonous, and foul-tasting critters developed their patterns of warning colors, there were numerous harmless animals living within close association with these species that, through the process of natural selection, acquired nearly identical color patterns for their own protection from predators. This form of defensive impersonation is known as Batesian mimicry.

Let’s take a look at some examples of Batesian mimicry right here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Suppose for a moment that you were a fly. As you might expect, you would have plenty to fear while you spend your day visiting flowers in search of energy-rich nectar—hundreds of hungry birds and other animals want to eat you.

If you were a fly and you were headed out and about to call upon numerous nectar-producing flowers so you could round up some sweet treats, wouldn’t you feel a whole lot safer if you looked like those venomous bees, wasps, and hornets in your neighborhood? Wouldn’t it be a whole lot more fun to look scary—so scary that would-be aggressors fear that you might sting them if they gave you any trouble?

Suppose Mother Nature and Father Time dressed you up to look like a bee or a wasp instead of a helpless fly? Then maybe you could go out and collect sweets without always worrying about the bullies and the brutes, just like these flies of the lower Susquehanna do…

FLOWER FLIES/HOVER FLIES

TACHINID FLIES

BEE FLIES

So let’s review. If you’re a poor defenseless fly and you want to get your fair share of sweets without being gobbled up by the beasts, then you’ve got to masquerade like a strongly armed member of a social colony—like a bee, wasp, or hornet. Now look scary and go get your treats. HAPPY HALLOWEEN!

What’s all this buzz about bees? And what’s a hymanopteran? Well, let’s see.

Hymanoptera—our bees, wasps, hornets and ants—are generally considered to be our most evolved insects. Some form complex social colonies. Others lead solitary lives. Many are essential pollinators of flowering plants, including cultivars that provide food for people around the world. There are those with stingers for disabling prey and defending themselves and their nests. And then there are those without stingers. The predatory species are frequently regarded to be the most significant biological controls of the insects that might otherwise become destructive pests. The vast majority of the Hymanoptera show no aggression toward humans, a demeanor that is seldom reciprocated.

Late summer and early autumn is a critical time for the Hymanoptera. Most species are at their peak of abundance during this time of year, but many of the adult insects face certain death with the coming of freezing weather. Those that will perish are busy, either individually or as members of a colony, creating shelter and gathering food to nourish the larvae that will repopulate the environs with a new generation of adults next year. Without abundant sources of protein and carbohydrates, these efforts can quickly fail. Protein is stored for use by the larval insects upon hatching from their eggs. Because the eggs are typically deposited in a cell directly upon the cache of protein, the larvae can begin feeding and growing immediately. To provide energy for collecting protein and nesting materials, and in some cases excavating nest chambers, Hymanoptera seek out sources of carbohydrates. Species that remain active during cold weather must store up enough of a carbohydrate reserve to make it through the winter. Honey Bees make honey for this purpose. As you are about to see, members of this suborder rely predominately upon pollen or insect prey for protein, and upon nectar and/or honeydew for carbohydrates.

We’ve assembled here a collection of images and some short commentary describing nearly two dozen kinds of Hymanoptera found in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the majority photographed as they busily collected provisions during recent weeks. Let’s see what some of these fascinating hymanopterans are up to…

SOLITARY WASPS

CUCKOO WASPS

SWEAT BEES

LEAFCUTTER AND MASON BEES

BUMBLE BEES, CARPENTER BEES, HONEY BEES, AND DIGGER BEES

SCOLIID WASPS

PAPER WASPS

YELLOWJACKETS AND HORNETS

POTTER WASPS

ANTS

We hope this brief but fascinating look at some of our more common bees, wasps, hornets, and ants has provided the reader with an appreciation for the complexity with which their food webs and ecology have developed over time. It should be no great mystery why bees and other insects, particularly native species, are becoming scarce or absent in areas of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where the landscape is paved, hyper-cultivated, sprayed, mowed, and devoid of native vegetation, particularly nectar-producing plants. Late-summer and autumn can be an especially difficult time for hymanopterans seeking the sources of proteins and carbohydrates needed to complete preparations for next year’s generations of these valuable insects. An absence of these staples during this critical time of year quickly diminishes the diversity of species and begins to tear at the fabric of the food web. This degradation of a regional ecosystem can have unforeseen impacts that become increasingly widespread and in many cases permanent.

Editor’s Note: No bees, wasp, hornets, or ants were harmed during this production. Neither was the editor swarmed, attacked, or stung. Remember, don’t panic, just observe.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

(If you’re interested in insects, get this book!)

If you’re like us, you’re forgoing this year’s egg hunt due to the prices, and, well, because you’re a little bit too old for such a thing.

Instead, we took a closer look at some of our wildlife photographs from earlier in the week. We’ve learned from experience that we don’t always see the finer details through the viewfinder, so it often pays to give each shot a second glance on a full-size screen. Here are a few of our images that contained some hidden surprises.

..but upon closer inspection we located…

..but after zooming in a little closer we found…

..but then, following further examination, we discovered…

THE BAD EGG

…but a careful search of the flock revealed…

It may look like just a puddle in the woods, but this is a very specialized wetland habitat, a habitat that is quickly disappearing from the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. It’s a vernal pool—also known as a vernal pond or an ephemeral (lasting a short time) pool or pond.

Viable vernal pools have several traits in common…

To have a closer look at what is presently living in this “black leaf” vernal pool, we’re calling on the crew of the S. S. Haldeman to go down under and investigate.

Let’s take it down for a better look. Dive, all dive!

We hope you enjoyed this quick look at life in a vernal pool. While the crew of the S. S. Haldeman decontaminates the vessel (we always scrub and disinfect the ship before moving between bodies of water) and prepares for its next voyage, you can learn more about vernal pools and the forest ecosystems of which they are such a vital component. Be sure to check out…

If you are a landowner or a land manager, you can find materials specifically providing guidance for protecting, restoring, and re-establishing vernal pool habitats at…

Neotropical birds are presently migrating south from breeding habitats in the United States and Canada to wintering grounds in Central and South America. Among them are more than two dozen species of warblers—colorful little passerines that can often be seen darting from branch to branch in the treetops as they feed on insects during stopovers in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Being nocturnal migrants, warblers are best seen first thing in the morning among sunlit foliage, often high in the forest canopy. After a night of flying, they stop to feed and rest. Warblers frequently join resident chickadees, titmice, and nuthatches to form a foraging flock that can contain dozens of songbirds. Migratory flycatchers, vireos, tanagers, and grosbeaks often accompany southbound warblers during early morning “fallouts”. Usually, the best way to find these early fall migrants is to visit a forest edge or thicket, particularly along a stream, a utility right-of-way, or on a ridge top. Then too, warblers and other Neotropical migrants are notorious for showing up in groves of mature trees in urban parks and residential neighborhoods—so look up!

Be sure to visit the Birds of Conewago Falls page by clicking the “Birds” tab at the top of this page. There, you’ll find photographs of the birds, including warblers and other Neotropical migrants, that you’re likely to encounter at locations throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

With autumn coming to a close, let’s have a look at some of the fascinating insects (and a spider) that put on a show during some mild afternoons in the late months of 2019.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

It’s sprayed with herbicides. It’s mowed and mangled. It’s ground to shreds with noisy weed-trimmers. It’s scorned and maligned. It’s been targeted for elimination by some governments because it’s undesirable and “noxious”. And it has that four letter word in its name which dooms the fate of any plant that possesses it. It’s the Common Milkweed, and it’s the center of activity in our garden at this time of year. Yep, we said milk-WEED.

Now, you need to understand that our garden is small—less than 2,500 square feet. There is no lawn, and there will be no lawn. We’ll have nothing to do with the lawn nonsense. Those of you who know us, know that the lawn, or anything that looks like lawn, are through.

Anyway, most of the plants in the garden are native species. There are trees, numerous shrubs, some water features with aquatic plants, and filling the sunny margins is a mix of native grassland plants including Common Milkweed. The unusually wet growing season in 2018 has been very kind to these plants. They are still very green and lush. And the animals that rely on them are having a banner year. Have a look…

We’ve planted a variety of native grassland species to help support the milkweed structurally and to provide a more complete habitat for Monarch butterflies and other native insects. This year, these plants are exceptionally colorful for late-August due to the abundance of rain. The warm season grasses shown below are the four primary species found in the American tall-grass prairies and elsewhere.

There was Monarch activity in the garden today like we’ve never seen before—and it revolved around milkweed and the companion plants.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

It’s been an atypical summer. The lower Susquehanna River valley has been in a cycle of heavy rains for over a month and stream flooding has been a recurring event. At Conewago Falls, the Pothole Rocks have been inundated for weeks. The location used as a lookout for the Autumn Migration Count last fall is at the moment submerged in ten feet of roaring water. Any attempt to tally the migrants which are passing thru in 2018 will thus be delayed indefinitely. Of greater import, the flooding at Conewago Falls is impacting many of the animals and plants there at a critical time in their annual life cycle. Having been displaced from its usual breeding sites on the river, one insect species in particular seems to be omnipresent in upland areas right now, and few people have ever heard of it.

So, you take a cruise in the motorcar to your favorite store and arrive at the sprawling parking lot. Not wishing to have your doors dented or paint chipped because you settled for a space tightly packed among other shopper’s conveyances, you park out there in the “boondocks”. You know the place, the lightly-used portion of the lot where sometimes brush grows from cracks in the asphalt and you must be on alert for impatient consumers who throttle-up to high speeds and dash diagonally across the carefully painted grids on the pavement to reach their favorite parking destination in the front row. Coming to a stop, you take the car out of gear, set the brake, disengage the safety belt, and gather your shopping list. You grasp the door handle and, not wanting to be flattened by one of the aforementioned motorists, you have a look around before exiting.

It was then that you saw the thing, hovering above your shiny bright hood. For a brief moment, it seemed to be peering right through the windshield at you with big reddish-brown eyes. In just a second or two, it turned its whole bronze body ninety degrees to the left and darted away on its cellophane wings. Maybe you didn’t really get a good look at it. It was so fast. But it certainly was odd. Oh well, time to walk inside a grab a few provisions. Away you go.

Upon completion of your shopping, you’re taking the long stroll back to your car and you notice more of these peculiar creatures. Two are coupled together and are hovering above someone’s automobile hood, then they drop down, and the lower of the two taps its abdomen on the paint. You ask yourself, “What are these bizarre things?”

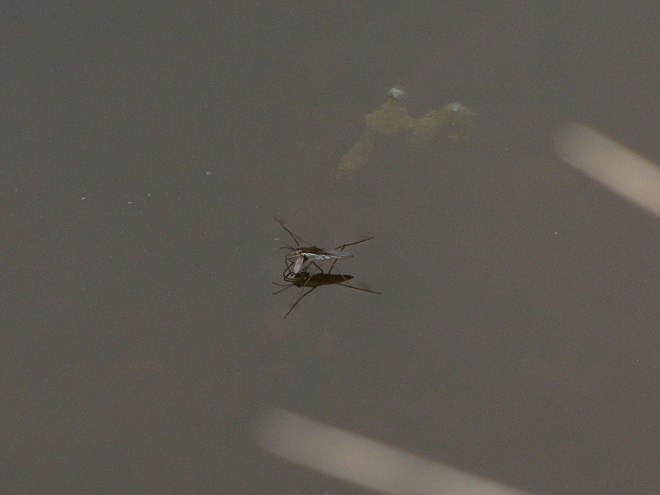

Meet the Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens), also known as the Globe Wanderer or Globe Skimmer, a wide-ranging dragonfly known to occur on every continent with the exception of Antarctica.

Wandering Gliders travel the globe, and as such are accomplished fliers. Adults spend most of the day on the wing, feeding upon a variety of flying insects. Days ago, I watched several intercepting a swarm of flying ants. As fast as ants left the ground they were grabbed and devoured by the gliders. Wandering Gliders are adept at taking day-flying mosquitos, often zipping stealthily past a person’s head or shoulders to grab one of the little pests—the would-be skeeter victim usually unaware of the whole affair.

Due to their nomadic life history, Wandering Gliders are opportunists when breeding and will lay eggs in most any body of freshwater. Their larvae do not overwinter prior to maturity; adults can be expected in a little more than one to two months. Repetitive flooding in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed this summer may be reducing the availability of the best local breeding sites for this species—riverine, stream, and floodplain pools of standing water with prey. This may explain why thousands of Wandering Gliders are patrolling parking lots, farmlands, and urban areas this summer. And it’s the likely reason for their use of puddles on asphalt pavement, on rubber roofs, and in fields as places to try to deposit eggs. Unfortunately, they may be as likely to succeed there as they are on your motor vehicle hood.

At this time a year ago, the airspace above the Diabase Pothole Rocks at Conewago Falls was jammed with territorial male Wandering Gliders. Each male hovered at various locations around his breeding territory consisting of pools and water-filled potholes. Intruders would quickly be dispatched from the area, then the male would resume his patrols from a set of repetitively-used hovering positions about six feet above the rocks. Mating and egg-laying continued into late September. The larvae, also called nymphs or naiads, were readily observed in many pools and potholes in early October and the emergence of juveniles was noted in mid-October. The absence of flooding, the mild autumn weather, and the moderation of water temperatures in the pools and potholes courtesy of the sun-drenched diabase boulders helped to extend the 2017 breeding season for Wandering Gliders in Conewago Falls. They aren’t likely to experience the same favor this year, but their great ability to travel and adapt should overcome this momentary misfortune.

There are two Conewago Creek systems in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. One drains the Gettysburg Basin west of the river, mostly in Adams and York Counties, then flows into the Susquehanna at the base of Conewago Falls. The other drains the Gettysburg Basin east of the river, flowing through Triassic redbeds of the Gettysburg Formation and York Haven Diabase before entering Conewago Falls near the south tip of Three Mile Island. Both Conewago Creeks flow through suburbia, farm, and forest. Both have their capacity to support aquatic life impaired and diminished by nutrient and sediment pollution.

This week, some of the many partners engaged in a long-term collaboration to restore the east shore’s Conewago Creek met to have a look at one of the prime indicators of overall stream habitat health—the fishes. Kristen Kyler of the Lower Susquehanna Initiative organized the effort. Portable backpack-mounted electrofishing units and nets were used by crews to capture, identify, and count the native and non-native fishes at sampling locations which have remained constant since prior to the numerous stream improvement projects which began more than ten years ago. Some of the present-day sample sites were first used following Hurricane Agnes in 1972 by Stambaugh and Denoncourt and pre-date any implementation of sediment and nutrient mitigation practices like cover crops, no-till farming, field terracing, stormwater control, nutrient management, wetland restoration, streambank fencing, renewed forested stream buffers, or modernized wastewater treatment plants. By comparing more recent surveys with this baseline data, it may be possible to discern trends in fish populations resulting not only from conservation practices, but from many other variables which may impact the Conewago Creek Warmwater Stream ecosystem in Dauphin, Lancaster, and Lebanon Counties.

So here they are. Enjoy these shocking fish photos.

SOURCES

Normandeau Associates, Inc. and Gomez and Sullivan. 2018. Muddy Run Pumped Storage Project Conowingo Eel Collection Facility FERC Project 2355. Prepared for Exelon.

Stambaugh, Jr., John W., and Robert P. Denoncourt. 1974. A Preliminary Report on the Conewago Creek Faunal Survey, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Proceedings of the Pennsylvania Academy of Sciences. 48: 55-60.

They can be a pesky nuisance. The annoying high-frequency buzzing is bad enough, but it’s the quiet ones that get you. While you were swatting at the noisy one, the silent gender sticks you and begins to feed. Maybe you know it, or maybe you don’t. She could make you itch and scratch. If she’s carrying a blood-borne pathogen, you could get sick and possibly die.

To humans, mosquitos are the most dangerous animal in the world (though not in the United States where man himself and the domestic dog are more of a threat). Globally, the Anopheles mosquitos that spread Malaria have been responsible for millions and millions of human deaths. Some areas of Africa are void of human habitation due to the prevalence of Malaria-spreading Anopheles mosquitos. In the northeastern United States, the Northern House Mosquito (Culex pipiens), as the carrier of West Nile Virus, is the species of greatest concern. Around human habitations, standing water in tires, gutters, and debris are favorite breeding areas. Dumping stagnant water helps prevent the rapid reproduction of this mosquito.

In recent years, the global distribution of these mosquito-borne illnesses has been one of man’s inadvertent accomplishments. An infected human is the source of pathogens which the feeding mosquito transmits to another unsuspecting victim. Infectious humans, traveling the globe, have spread some of these diseases to new areas or reintroduced them to sectors of the world where they were thought to have been eliminated. Additionally, where the specific mosquito carrier of a disease is absent, the mobility of man and his cargos has found a way to transport them there. Aedes aegypti, the “Yellow Fever Mosquito”, carrier of its namesake and the Zeka Virus, has found passage to much of the world including the southern United States. Unlike other species, Aedes aegypti dwells inside human habitations, thus transmitting disease rapidly from person to person. Another non-native species, the Asian Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus), vector of Dengue Fever in the tropics, arrived in Houston in 1985 in shipments of used tires from Japan and in Los Angeles in 2001 in wet containers of “lucky bamboo” from Taiwan…some luck.

Poor mosquito, despite the death, suffering, and misery it has brought to Homo sapiens and other species around the planet, it will never be the most destructive animal on earth. You, my bloodthirsty friends, will place second at best. You see, mosquitos get no respect, even if they do create great wildlife sanctuaries by scaring people away.

The winner knows how to wipe out other species and environs not only to ensure its own survival, but, in many of its populations, to provide leisure, luxury, gluttony, and amusement. This species possesses the cognitive ability to think and reason. It can contemplate its own existence and the concepts of time. It is aware of its history, the present, and its future, though its optimism about the latter may be its greatest delusion. Despite possessing intellect and a capacity to empathize, it is devious, sinister, and selfish in its treatment of nearly every other living thing around it. Its numbers expand and its consumption increases. It travels the world carrying pest and disease to all its corners. It pollutes the water, land, and air. It has developed language, culture, and social hierarchies which create myths and superstitions to subdue the free will of its masses. Ignoring the gift of insight to evaluate the future, it continues to reproduce without regard for a means of sustenance. It is the ultimate organism, however, its numbers will overwhelm its resources. The crowning distinction will be the extinction.

Homo sapiens will be the first animal to cause a mass extinction of life on earth. The forces of nature and the cosmos need to wait their turn; man will take care of the species annihilation this time around. The plants, animals, and clean environment necessary for a prosperous healthy life will cease to exist. In the end, humans will degenerate, live in anguish, and leave no progeny. Fate will do to man what he has done to his co-inhabitants of the planet.

Avery, Dennis T. 1995. Saving the Planet with Pesticides and Plastic: The Environmental Triumph of High-Yield Farming. Hudson Institute. Indianapolis, Indiana.

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Co. New York.

Newman, L.H. 1965. Man and Insects. The Natural History Press. Garden City, New York.