Following a frosty night, sunny skies and a south breeze brought lots of action to the headquarters garden this morning. Take a look…

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Following a frosty night, sunny skies and a south breeze brought lots of action to the headquarters garden this morning. Take a look…

To take advantage of this unusually mild late-winter day, observers arrived by the thousands to have a look at an even greater number of migratory birds gathered at the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area. Here are some highlights…

Now is a great time of year to see Bald Eagles in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. For the population that breeds here in our region, it’s nesting season. These birds are defending territories and some of them can get pretty aggressive towards the other eagles that happen to be wintering in the Susquehanna valley or will be migrating north through the area in coming weeks. All that competition has these birds spending a lot of time in the air, so no matter where you happen to be, keeping an eye on the sky may provide you with an opportunity for a memorable glimpse of one or more eagles in action. Skeptical? Well, just an hour ago, we spotted these eagles high above the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters garden.

So do spend some time outdoors soon and while you’re there, don’t forget to look up. You might turn some of your time into Bald Eagle time too!

As week-old snow and ice slowly disappears from the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed landscape, we ventured out to see what might be lurking in the dense clouds of fog that for more than two days now have accompanied a mid-winter warm spell.

If scenes of a January thaw begin to awaken your hopes and aspirations for all things spring, then you’ll appreciate this pair of closing photographs…

As anticipated, lakes and ponds throughout the lower Susquehanna basin are beginning to freeze. Fortunately for the waterfowl thereon, particularly diving ducks, the rain-swollen river is slowly receding and water clarity is improving to provide a suitable alternative to life on the man-made impoundments.

The deep freeze is not only impacting ponds and lakes in the lower Susquehanna valley, but is evidently affecting the larger bodies of water to our north and northwest. During Tuesday’s snow event, thousands of diving ducks arrived on the main stem of the river—apparently forced down by the inclement weather while en route to the Atlantic Coast from the Great Lakes and its connected waterways, which are currently beginning to freeze.

With more snow on the way for tomorrow, you may be wondering if another fallout like this could be in the works. The only way to find out is to get out there and have a look. Good luck! And be good!

With the earth at perihelion (its closest approach to the sun) and with our home star just 27 degrees above the horizon at midday, bright low-angle light offered the perfect opportunity for doing some wildlife photography today. We visited a couple of grasslands managed by the Pennsylvania Game Commission to see what we could find…

As the autumn raptor migration draws to a close in the Lower Susquehanna Valley Watershed, observers at the Second Mountain Hawk Watch in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, were today treated to a flight of both Bald and Golden Eagles. Gliding on updrafts created by a brisk northwest breeze striking the slope of the ridge, seven of the former and three of the latter species were seen threading their way through numerous bands of snow as they made their way southwest toward favorable wintering grounds.

The best and final bird of the day, and possibly one of the highlights of the season at this counting station, was a “Barthelemyi Golden Eagle”, a rare Golden Eagle variant with conspicuous shoulder epaulets created by white scapular feathers.

Today’s rarity is the second record of a “Barthelemyi Golden Eagle” at Second Mountain Hawk Watch—the first occurring on October 21, 2017.

SOURCES

Spofford, W. R. 1961. “White Epaulettes in Some Appalachian Golden Eagles”. Prothonotary. 27: 99.

While trimming the trees and shrubs in the susquehannawildlife.net garden, it didn’t seem particularly unusual to hear the resident Carolina Chickadees and Carolina Wrens scolding our every move. But after a while, their persistence did seem a bit out of the ordinary, so we took a little break to have a look around…

Here at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, we are visited by Cooper’s Hawks for several days during the late fall and winter each year. The small birds that visit our feeders have plenty of trees, shrubs, vines, and other natural cover in which to hide from raptors and other native predators. We don’t create unnatural concentrations of birds by dumping food all over the place. We try to keep our small birds healthy by sparingly offering fresh seed and other provisions in clean receptacles to provide a supplement to the seeds, fruits, insects, and other foods that occur naturally in the garden. With only a few vulnerable small birds around, the Cooper’s Hawks visit just long enough to cull out our weakest individuals before moving elsewhere. While they’re in our garden, they too are our welcomed guests.

Colder temperatures and gusty northwest winds are prompting our largest migratory raptors to continue their southward movements. Here are some of the birds seen earlier today riding updrafts of air currents along one of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s numerous ridges.

As winter begins clawing at the door, now is great time to visit a hawk watch near you to see these late-season specialties. Remember to dress in layers and to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page. Hawkwatcher’s Helper is your guide to regional hawk watching locations and raptor identification. Be sure to check it out. And remember, it’s cold on top of those ridges, so don’t forget your hat, your gloves, and your chap stick!

With nearly all of the Neotropical migrants including Broad-winged Hawks gone for the year, observers and counters at eastern hawk watches are busy tallying numbers of the more hardy species of diurnal raptors and other birds. The majority of species now coming through will spend the winter months in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the southern United States and Mexico.

Here is a quick look at the raptors seen this week at two regional counting stations: Kiptopeke Hawk Watch near Cape Charles, Virginia, and Second Mountain Hawk Watch at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania.

During coming days, fewer and fewer of these birds will be counted at our local hawk watches. Soon, the larger raptors—Red-tailed Hawks, Red-shouldered Hawks, and Golden Eagles—will be thrilling observers. Cooler weather will bring several flights of these spectacular species. Why not plan a visit to a lookout near you? Click on the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page for site information and a photo guide to identification. See you at the hawk watch!

Tropical Storm Ophelia has put the brakes on a bustling southbound exodus of the season’s final waves of Neotropical migrants. Winds from easterly directions have now beset the Mid-Atlantic States with gloomy skies, chilly temperatures, and periods of rain for an entire week. These conditions, which are less than favorable for undertaking flights of any significant distance, have compelled many birds to remain in place—grounded to conserve energy.

Of the birds on layover, perhaps the most interesting find has been a western raptor that occurs only on rare occasions among the groups of Broad-winged Hawks seen at hawk watches each fall—a Swainson’s Hawk. Discovered as Tropical Storm Ophelia approached on September 21st, this juvenile bird has found refuge in coal country on a small farm in a picturesque valley between converging ridges in southern Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. Swainson’s Hawks are a gregarious species, often spending time outside of the nesting season in the company of others of their kind. Like Broad-winged Hawks, they frequently assemble into large groups while migrating.

Swainson’s Hawks nest in the grasslands, prairies, and deserts of western North America. Their autumn migration to wintering grounds in Argentina covers a distance of up to 6,000 miles. Among raptors, such mileage is outdone only by the Tundra Peregrine Falcon.

During the nesting cycle, Swainson’s Hawks consume primarily small vertebrates, mostly mice and other small rodents. But during the remainder of the year, they feed almost exclusively on grasshoppers. To provide enough energy to fuel their migrations, they must find and devour these insects by the hundreds. Not surprisingly, the Swainson’s Hawk is sometimes known as the Grasshopper Hawk or Locust Hawk, particularly in the areas of South America where they are common.

So just how far will our wayward Swainson’s Hawk have to travel to get back on track? Small numbers of Swainson’s Hawks pass the winter in southern Florida each year and still others are found in and near the scrublands of the Lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas and Mexico. But the vast majority of these birds make the trip all the way to the southern half of South America and the farmlands and savannas of Argentina—where our winter is their summer. The best bet for this bird would be to get hooked up with some of the season’s last Broad-winged Hawks when they start flying in coming days, then join them as they head toward Houston, Texas, to make the southward turn down the coast of the Gulf of Mexico into Central America and Amazonia. Then again, it may need to find its own way to warmer climes. Upon reaching at least the Gulf Coastal Plain, our visitor stands a much better chance of surviving the winter.

“Waves” of warblers and other Neotropical songbirds continue to roll along the ridgetops of southern Pennsylvania. The majority of these migrants are headed to wintering habitat in the tropics after departing breeding grounds in the forests of southern Canada. At Second Mountain Hawk Watch, today’s early morning flight kicked off at sunrise, then slowed considerably by 8:30 A.M. E.D.T. Once again, in excess of 400 warblers were found moving through the trees and working their way southwest along the spine of the ridge. Each of the 12 species seen yesterday were observed today as well. In addition, there was a Northern Parula and a Canada Warbler. Today’s flight was dominated by Bay-breasted, Blackburnian, Black-throated Green, and Tennessee Warblers.

Other interesting Neotropical migrants joined the “waves” of warblers…

During the recent couple of mornings, a tide of Neotropical migrants has been rolling along the crests of the Appalachian ridges and Piedmont highlands of southern Pennsylvania. In the first hours of daylight, “waves” of warblers, vireos, flycatchers, tanagers, and other birds are being observed flitting among the sun-drenched foliage as they feed in trees along the edges of ridgetop clearings. Big fallouts have been reported along Kittattiny Ridge/Blue Mountain at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and at Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch. Birds are also being seen in the Furnace Hills of the Piedmont.

Here are some of the 300 to 400 warblers (a very conservative estimate) seen in a “wave” found working its way southwest through the forest clearing at the Second Mountain Hawk Watch in Lebanon County this morning. The feeding frenzy endured for two hours between 7 and 9 A.M. E.D.T.

Not photographed but observed in the mix of species were several Black-throated Blue Warblers and American Redstarts.

In addition to the warblers, other Neotropical migrants were on the move including two Common Nighthawks, a Broad-winged Hawk, a Least Flycatcher (Empidonax minimus), and…

Then, there was a taste of things to come…

Seeing a “wave” flight is a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Visiting known locations for observing warbler fallouts such as hawk watches, ridgetop clearings, and peninsular shorelines can improve your chances of witnessing one of these memorable spectacles by overcoming the first variable. To overcome the second, be sure to visit early and often. See you on the lookout!

As we enter September, autumn bird migration is well underway. Neotropical species including warblers, vireos, flycatchers, and nighthawks are already headed south. Meanwhile, the raptor migration is ramping up and hawk watch sites throughout the Mid-Atlantic States are now staffed and counting birds. In addition to the expected migrants, there have already been sightings of some unusual post-breeding wanderers. Yesterday, a Wood Stork (Mycteria americana) was seen passing Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and a Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus) that spent much of August in Juniata County was seen from Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch while it was hunting in a Perry County field six miles to the north of the lookout! Both of these rarities are vagrants from down Florida way.

To plan a visit to a hawk watch near you, click on the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page to find a list and brief description of suggested sites throughout the Mid-Atlantic region. “Hawkwatcher’s Helper” also includes an extensive photo guide for identifying the raptors you’re likely to see.

And to identify those confusing fall warblers and other migrants, click the “Birds” tab at the top of this page and check out the photo guide contained therein. It includes nearly all of the species you’re likely to see in the lower Susquehanna valley.

If you’re feeling the need to see summertime butterflies and their numbers just don’t seem to be what they used to be in your garden, then plan an afternoon visit to the Boyd Big Tree Preserve along Fishing Creek Valley Road (PA 443) just east of U.S. 22/322 and the Susquehanna River north of Harrisburg. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources manages the park’s 1,025 acres mostly as forested land with more than ten miles of trails. While located predominately on the north slope of Blue Mountain, a portion of the preserve straddles the crest of the ridge to include the upper reaches of the southern exposure.

Fortunately, one need not take a strenuous hike up Blue Mountain to observe butterflies. Open space along the park’s quarter-mile-long entrance road is maintained as a rolling meadow of wildflowers and cool-season grasses that provide nectar for adult butterflies and host plants for their larvae.

Do yourself a favor and take a trip to the Boyd Big Tree Preserve Conservation Area. Who knows? It might actually inspire you to convert that lawn or other mowed space into much-needed butterfly/pollinator habitat.

While you’re out, you can identify your sightings using our photographic guide—Butterflies of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed—by clicking the “Butterflies” tab at the top this page. And while you’re at it, you can brush up on your hawk identification skills ahead of the upcoming migration by clicking the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab. Therein you’ll find a listing and descriptions of hawk watch locations in and around the lower Susquehanna region. Plan to visit one or more this autumn!

Mid-summer can be a less than exciting time for those who like to observe wild birds. The songs of spring gradually grow silent as young birds leave the nest and preoccupy their parents with the chore of gathering enough food to satisfy their ballooning appetites. To avoid predators, roving families of many species remain hidden and as inconspicuous as possible while the young birds learn how to find food and handle the dangers of the world.

But all is not lost. There are two opportunities for seeing unique birds during the hot and humid days of July.

First, many shorebirds such as sandpipers, plovers, dowitchers, and godwits begin moving south from breeding grounds in Canada. That’s right, fall migration starts during the first days of summer, right where spring migration left off. The earliest arrivals are primarily birds that for one reason on another (age, weather, food availability) did not nest this year. These individuals will be followed by birds that completed their breeding cycles early or experienced nest failures. Finally, adults and juveniles from successful nests are on their way to the wintering grounds, extending the movement into the months we more traditionally start to associate with fall migration—late August into October.

For those of you who find identifying shorebirds more of a labor than a pleasure, I get it. For you, July can bring a special treat—post-breeding wanderers. Post-breeding wanderers are birds we find roaming in directions other than south during the summer months, after the nesting cycle is complete. This behavior is known as “post-breeding dispersal”. Even though we often have no way of telling for sure that a wandering bird did indeed begin its roving journey after either being a parent or a fledgling during the preceding nesting season, the term post-breeding wanderer still applies. It’s a title based more on a bird sighting and it’s time and place than upon the life cycle of the bird(s) being observed. Post-breeding wanderers are often southern species that show up hundreds of miles outside there usual range, sometimes traveling in groups and lingering in an adopted area until the cooler weather of fall finally prompts them to go back home. Many are birds associated with aquatic habitats such as shores, marshes, and rivers, so water levels and their impact on the birds’ food supplies within their home range may be the motivation for some of these movements. What makes post-breeding wanderers a favorite among many birders is their pop. They are often some of our largest, most colorful, or most sought-after species. Birds such as herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, stilts, avocets, terns, and raptors are showy and attract a crowd.

While it’s often impossible to predict exactly which species, if any, will disperse from their typical breeding range in a significant way during a given year, some seem to roam with regularity. Perhaps the most consistent and certainly the earliest post-breeding wanderer to visit our region is the “Florida Bald Eagle”. Bald Eagles nest in “The Sunshine State” beginning in the fall, so by early spring, many of their young are on their own. By mid-spring, many of these eagles begin cruising north, some passing into the lower Susquehanna valley and beyond. Gatherings of dozens of adult Bald Eagles at Conowingo Dam during April and May, while our local adults are nesting and after the wintering birds have gone north, probably include numerous post-breeding wanderers from Florida and other Gulf Coast States.

So this week, what exactly was it that prompted hundreds of birders to travel to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area from all over the Mid-Atlantic States and from as far away as Colorado?

Was it the majestic Great Blue Herons and playful Killdeer?

Was it the colorful Green Herons?

Was it the Great Egrets snapping small fish from the shallows?

Was it the small flocks of shorebirds like these Least Sandpipers beginning to trickle south from Canada?

All very nice, but not the inspiration for traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles to see a bird.

It was the appearance of this very rare post-breeding wanderer…

…Pennsylvania’s first record of a Limpkin, a tropical wading bird native to Florida, the Caribbean Islands, and South America. Many observers visiting Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area had never seen one before, so if they happen to be a “lister”, a birder who keeps a tally of the wild bird species they’ve seen, this Limpkin was a “lifer”.

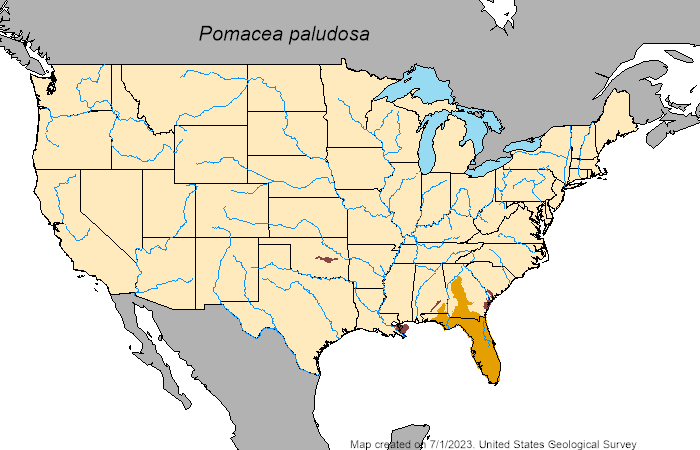

The Limpkin is an inhabitant of vegetated marshlands where it feeds almost exclusively upon large snails of the family Ampullariidae, including the Florida Applesnail (Pomacea paludosa), the largest native freshwater snail in the United States.

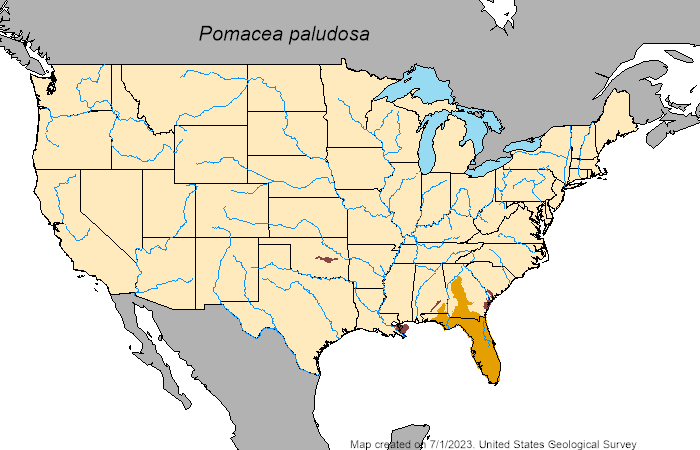

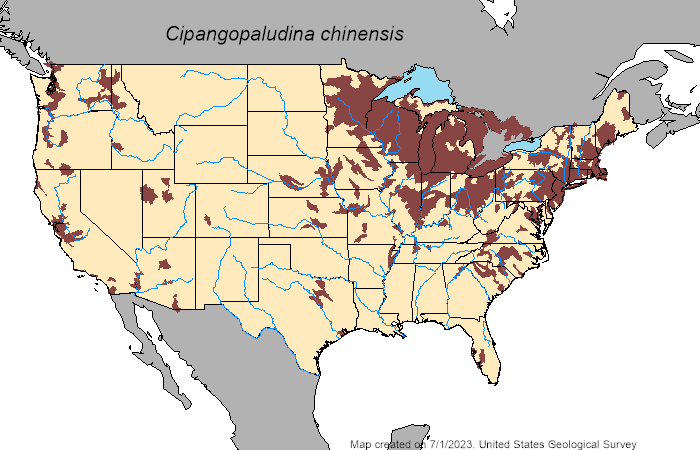

Observations of the Limpkin lingering at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area have revealed a pair of interesting facts. First, in the absence of Florida Applesnails, this particular Limpkin has found a substitute food source, the non-native Chinese Mystery Snail (Cipangopaludina chinensis). And second, Chinese Mystery Snails have recently become established in the lakes, pools, and ponds at the refuge, very likely arriving as stowaways on Spatterdock (Nuphar advena) and/or American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea), native transplants brought in during recent years to improve wetland habitat and process the abundance of nutrients (including waterfowl waste) in the water.

The Middle Creek Limpkin’s affinity for Chinese Mystery Snails may help explain how it was able to find its way to Pennsylvania in apparent good health. Look again at the map showing the range of the Limpkin’s primary native food source, the Florida Applesnail. Note that there are established populations (shown in brown) where these snails were introduced along the northern coast of Georgia and southern coast of South Carolina…

…now look at the latest U.S.G.S. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species map showing the ranges (in brown) of established populations of non-native Chinese Mystery Snails…

…and now imagine that you’re a happy-go-lucky Limpkin working your way up the Atlantic Coastal Plain toward Pennsylvania and taking advantage of the abundance of food and sunshine that summer brings to the northern latitudes. It’s a new frontier. Introduced populations of Chinese Mystery Snails are like having a Waffle House serving escargot at every exit along the way!

Be sure to click the “Freshwater Snails” tab at the top of this page to learn more about the Chinese Mystery Snail and its arrival in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Once there, you’ll find some additional commentary about the Limpkin and the likelihood of Everglade Snail Kites taking advantage of the presence of Chinese Mystery Snails to wander north. Be certain to check it out.

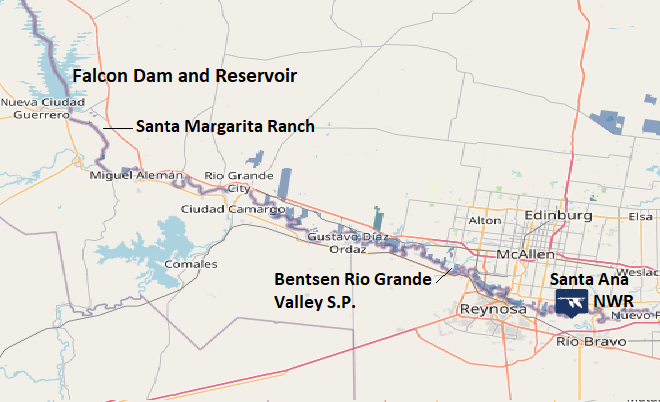

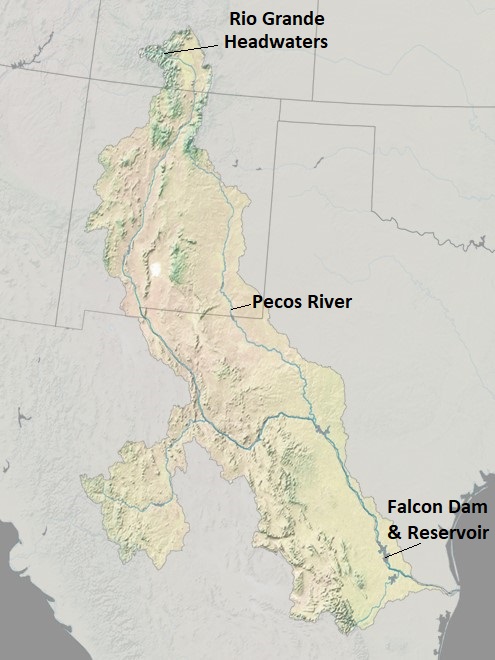

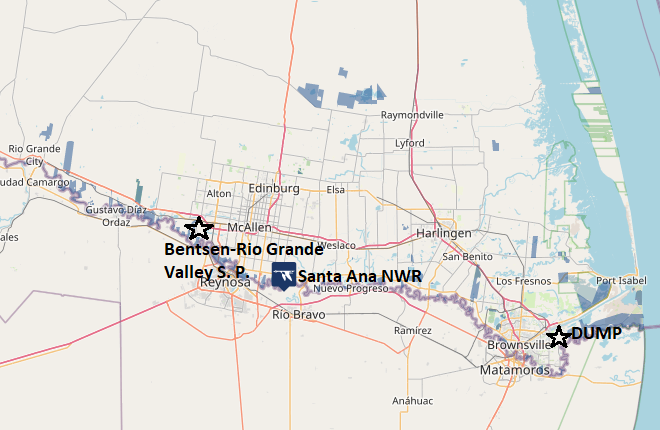

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY NINE—May 29, 1983

“Falcon Dam State Park, Texas”

“To the spillway area after breakfast and saw Ringed Kingfisher, Baird’s Sandpiper, and 2 Black-necked Stilts. Stopped to photograph the Swainson’s Hawk which had flown in a tree. Also saw a Blue Grosbeak.”

The Ringed Kingfisher (Megaceryle torquata) was notably larger than the Belted Kingfishers with which we were so familiar, so it was easy to identify. This was yet another tropical species found north only as far as the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Baird’s Sandpiper was a pretty good find for this location in late May.

“We drove to Santa Margarita Ranch to search for the elusive Brown Jay.”

While en route to Santa Margarita Ranch, we stopped twice to photograph birds we spotted along the way.

Beside the road just outside the entrance to the ranch, we observed a Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps), a tiny chickadee-like like bird with a yellow head and throat. Verdins reside in both thornscrub and desert throughout the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

“Rancho Santa Margarita is a group of 8 houses. Cattle roam at will. We walked a long way along the river — No luck. Had lunch in the camper and repeated the morning walk. Cattle dung all over the place. The dung rollers were as interesting to watch as the leaf-carrying ants. Met a Mr. McQueary who had seen them 30 min. ago, so he led us to where he had seen them, but — No luck.”

Upon arriving at Santa Margarita Ranch intending to find Brown Jays (Psilorhinus morio), we drove over the in-ground cattle gate at the entrance and back the dirt driveway to the small cluster of houses where we parked. We checked in with a resident there and slipped them a dollar or two a head for letting us spend the day on their land. As we walked away from the houses, we noticed some intermittent movement in a pile of construction debris along the dirt road leading to the river. Initially thinking we may have caught glimpses of some small rodents dashing around, we watched patiently until we saw at least two Blue Spiny Lizards (Sceloporus cyanogenys) among the lumber and tin. The pair was obviously finding insects or other sources of prey there

To find Brown Jays, one of the five target species of the trip, Father Tom had advised us to follow the advice in James Lane’s A Birder’s Guide to the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. The recommendations contained therein brought us to Santa Margarita Ranch. As was the case upriver near Falcon Dam, the Tamaulipan Saline Thornscrub that covers much of the property turns abruptly to subtropical riparian forest near the banks of the Rio Grande where wetter soils predominate. The habitat was excellent, and we were certain the birds were there, but despite significant effort, we just couldn’t bump into Brown Jays at Santa Margarita Ranch.

We did however get good looks at another Hook-billed Kite sailing above the trees downriver. During our second walk, Harold, Steve, and I waded down a short section of the Rio Grande in hopes of getting better looks into an area of shoreline forest too thick to enter by land. Despite recent rains, the water was low, restricted by gates at Falcon Dam to little more than the flow needed to operate the turbines and generate electricity. We saw orioles, Red-billed Pigeon, and Great Kiskadee—but no Brown Jays.

“On the way out…found a nest of Pyrrhuloxia and saw a 6 ft. snake hanging from a bush with a rabbit in his mouth. The snake caught the rabbit by the shoulder and it was working hard to get free. Finally the snake dropped the rabbit, and they both went out of sight.”

As we eased our way out the dirt road at Santa Magarita Ranch, we began hearing a blood-curdling series of squeals. Russ stopped the van and as we peered into the thornscrub, we could catch glimpses of an Eastern Cottontail thrashing around. At first we thought it had somehow become snagged in the quagmire of prickles on the dense vegetation. Then we spotted the snake draped over the shrubs and attempting in vain to lift the cottontail off the ground. The struggle, and the squealing, continued for several minutes as we labored to identify the snake. As the snake attempted to reposition the cottontail so that it could swallow it head first, the rabbit broke free and escaped. All was silent as the snake quickly fled as well. As it slithered away we could see just how long it really was—5 to 6 feet or more. You know, things really are bigger in Texas. Based upon its large size, overall tan-brown color, and the rapid speed with which it left the scene, we determined it was a Western Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum testaceus).

“Back to the spillway at Falcon Dam — No luck. Met Ron Huffman who is leading a trip for 3 women. We will meet him at the spillway tomorrow AM early. Back at our camp site for supper — shower and shave. The Lesser Nighthawks were trilling late in the evening.”

During the evening, we found Black-throated Sparrow (Amphispiza bilineata) and Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata) in the area of the campsite. Then, as darkness settled in, the calls of Common Pauraque, Common Nighthawks, and Lesser Nighthawks (Chordeiles acutipennis) commenced. We walked down the road to a spot where we could overlook a lower-lying area of thornscrub in hopes of catching a glimpse of some of these nightjars, particularly the latter species, as they patrolled for flying insects. But under cloudy skies and being miles from any man-made sources of light, it was too dark to see anything flying around.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY EIGHT—May 28, 1983

“Bentsen State Park, Texas”

“Alarm at 6:00 A.M. After breakfast we traveled to Falcon State Park and toured the whole camp area, stopping many places to observe birds. We ran up a good list.”

And so we left what had been our home for the last several days and headed west. In the forty years since our departure that morning, Bentsen-Rio Grande State Park has experienced a number of operational changes. Today, it is a World Birding Center site. For conducting the seasonal hawk census, a tower has been erected to provide counters and observes with an unrestricted view above the treetops. If you wanted to camp in the park now, you would need reservations and would have to hike your gear in to one of only a few primitive campsites. Trailer and motor home accommodations no longer exist. A tram service is now available for touring the park by motor vehicle.

Falcon State Park is located along the east shore of Falcon Reservoir. There are no shade trees beneath which one can escape the scorching rays of the sun on a hot day. This is the easternmost section of the scrubland’s Tamaulipan Saline Thornscrub, a xeric plant community of head-high brush found only on clay soils with a particularly high salinity. Many of the plants look similar to other varieties of shrubs and small trees with which one may be familiar, except nearly all of them are covered with nasty thorns and prickles. And yes, there are cactus. You can’t make your way bushwhacking cross country without obtaining cuts, gashes, and scars to show for it. The Falcon State Recreation Area bird checklist published in 1977 has a nice description of the plants found there—mesquite, ebano, guaycan, blackbrush and catclaw acacia, granjeno, coyotillo, huisache, tasajillo, prickly pear, allthorn, cenizo, colima, and yucca. In the margins between the thornscrub growth, there is an abundance of grasses and wildflowers. On nearby ridges, Tamaulipan Calcareous Thornscrub, a similar xeric plant community, occupies soils with a higher content of calcium carbonate. Together, these communities comprise much of the Tamaulipan Mezquital ecoregion of scrublands in Starr County and western Hidalgo County in the Rio Grande valley of Texas.

After being greeted by a Greater Roadrunner at the campsite, we took a walk to the nearby shoreline of the reservoir. We spotted Olivaceous Cormorants perched on some dead limbs in the water nearby. Known today as Neotropic Cormorant (Phalacrocorax brasilianus), it is yet another specialty of the Rio Grande Valley. Elsewhere on or near the water—Cattle Egret, Great Egret, Black-bellied Whistling Duck, Osprey, Common Gallinule, Killdeer, Laughing Gull, Forster’s Tern (Sterna forsteri), Least Tern, and Caspian Tern were seen.

In the thornscrub around the campground, which, like Bentsen-Rio Grande State Park, we had pretty much to ourselves, we saw Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Curve-billed Thrasher, White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, Ground Dove, Inca Dove, and White-tipped Dove. A single Chihuahuan Raven was a fly by. We saw and smelled several road-killed Nine-banded Armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), but never found one alive.

Then, it started to rain. Not just a shower, but a soaker that persisted through much of the day. Rainy days can make for great birding, so we kept at it. Unfortunately, such days aren’t too ideal for photography, so we did only what we could without ruining our equipment.

“Finally we drove to the spillway of the dam and parked.”

Falcon Dam was another of the numerous flood-control projects built on the Rio Grande during the middle of the twentieth century. Behind it, Falcon Reservoir stores water for irrigation and operation of a hydroelectric generating station located within the dam complex. Construction of the dam and power plant was a joint venture shared by Mexico and the United States. The project was dedicated by Presidents Adolfo Ruiz Cortines and Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953.

Rainy days aside, the route precipitation takes to reach the Falcon Reservoir and the Lower Rio Grande Valley includes hundreds of miles through arid grasslands and scrublands. Along the way, much of that water is lost to natural processes including evaporation and aquifer recharge, but an increasing percentage of the volume is being removed by man for civil, industrial, and agricultural uses. Can the Rio Grande and its tributaries continue to meet demand?

“On the way in we saw and photographed an apparent sick or injured Swainson’s Hawk. We approached it very close.”

“At the spillway we sat in the camper, except when the rain slackened, then we stood out and watched in vain for the Green or Ringed Kingfisher, which we never did see.”

At the spillway House Sparrows, Rough-winged Swallows, and Cliff Swallows were nesting on the dam, the latter two species grabbing flying insects above the waters of the Rio Grande.

“I made dinner here at this spillway and we continued to watch. The rain almost stopped, so we walked down the road about 1 1/2 miles, during which time we saw a lifer for Harold — Hook-billed Kite. We followed Father Tom’s directions to a spot for the Ferruginous Owl — no luck.”

“Back at the spillway we had supper and then repeated the hike — no Ferruginous Owl, but a Barn Owl and Great Horned Owl. Back to our #201 campsite and wrote up the day’s log.”

Trees along the river provided habitat for orioles and other species. Since the rain had subsided, we decided to see what might come out and begin feeding. Soon, we not only saw an Altamira Oriole, but found Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus) and the yellow and black tropical species, Audubon’s Oriole (Icterus graduacauda), formerly known as Black-headed Oriole. Three species of orioles on a backdrop of lush green subtropical foliage, it was magnificent.

Along the dirt road below the dam, the mix of scrubland and subtropical riparian forest made for excellent birding. We not only found a soaring Hook-billed Kite, one of the target birds for the trip, but we had good looks at both a Great Horned Owl, then a Barn Owl (Tyto alba) that we flushed from the bare ground in openings among the vegetation as we walked the through. Both had probably pounced on some sort of small prey species prior to our arrival. Because there are seldom crows or ravens to bother them, owls here are more active during than day than they are elsewhere. The subject of this afternoon’s intensive search, the elusive and diminutive Ferruginous Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium brasilianum), is routinely diurnal. Other sightings on our two walks included Turkey Vulture, Black Vulture, White-tailed Kite, Northern Bobwhite, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Ladder-backed Woodpecker, Couch’s Kingbird, Brown-crested Flycatcher, Green Jay, Black-crested Titmouse, Mockingbird, Long-billed Thrasher, Great-tailed Grackle, Bronzed Cowbird, Northern Cardinal, and Painted Bunting.

The day finished as so many others had earlier during the trip—with insect-hunting Common Nighthawks calling from the skies around our campsite.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY SIX—May 26, 1983

“Bentsen State Park — Texas”

“Arose at 7:30. Birded the park and watched for the reported Roadside Hawk. No luck. A Roadrunner and Kiskadee was a welcome addition to our list.”

The appearance of Roadside Hawk (Rupornis magnirostris) north of the Rio Grande in Hidalgo County, Texas, was hot news in 1983. In the weeks leading up to our visit and while we were there, no sightings of this mega-rarity were confirmed. The reports that were received were not accompanied by photographs or sufficient details to rule out the Hook-billed Kites (Chondrohierax unicinatus) and Cooper’s Hawks that were known to be present. Roadside Hawk remains a very elusive tropical vagrant in the United States. It was seen as recently as December of 2018 along the man-made flood control levee to the east of Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park near the Border Patrol Corral and the adjacent National Butterfly Center, neither of which were present in 1983.

Both the Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), a familiar member of the cuckoo family (Cuculidae), and the Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus), a flycatcher at the northern limit of its range in south Texas, were much anticipated finds at Bentsen-Rio Grande State Park. We would get better looks at both when we moved to the west in a couple of days.

“Traveled to Brownsville and met Harold and Steve at the airport at 12:30 P.M.”

Back in 1983, the Brownsville Airport was the most frequently used destination for those wanting to fly into the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Today, Valley International Airport in Harlingen is the busier of the two. Both of these airports have an interesting history from the World War II years. Brownsville Airport, renamed Brownsville Army Air Field for the duration of the war, was in use as a base for antisubmarine warfare flights, pilot training, aircraft engine overhauls, and the occasional servicing of B-29 bombers. The airport in Harlingen was founded during the period as Harlingen Army Air Field and was home to the Harlingen Aerial Gunnery School. A cheesy Hollywood propaganda movie called Aerial Gunner (1943) was shot there in late 1942 and starred Richard Arlen and a local actress, Amelita (Lita) Ward, who was discovered by the picture’s producers in Harlingen during the early stages of filming. A young Robert Mitchum portrays one of the gunners. It’s one of those typical B-movies of the period with a story line that is all mixed up with what happened years ago. A climactic part of the film depicts students being taken aloft to fire machine guns at kite-like targets being towed behind other training aircraft flying over the nearby Gulf of Mexico. You can find this classic and watch it for free on the internet. Afterward, you can go join up if you want, but you can no longer get the war bonds they were selling.

“We tried for the Clay-colored Robin — No Luck.”

Now that Harold and Steve had joined us, we began putting in an earnest effort to find the five species we all needed for our life lists—those Lower Rio Grande Valley exclusives Father Tom had given us directions to find. First up was Clay-colored Robin, known today as Clay-colored Thrush (Turdus grayi), a brown-colored bird similar to our American Robin. Its native range in 1983 was from northern Colombia north to the Rio Grande River. The only pair known to be reliably nesting north of the river in the United States, thus within the A.B.A. listing area, was in Brownsville in a park-like setting on the side of a small hill with a commercial radio station transmitter and antenna on its crest. It was an easy place to find in the otherwise flat landscape, but we had no luck finding the birds. Were we too late? Was nesting season over? Had the birds already dispersed?

“Visited Santa Ana again and added Ground Dove and White-tailed (Black-shouldered) Kite.”

Father Tom provided us with a tip that Hook-billed Kites had nested in the vicinity of Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. We remained vigilant, but saw none. The petite Common Ground Dove (Columbina passerina) was harder to locate than I expected, possibly because its small size makes it more prone to depredation than larger doves and pigeons, so it may be a little more secretive. White-tailed Kite (Elanus leucurus) sightings were a highlight of the trip, so graceful and stunning in appearance, but very wary and distant—not a good photo opportunity. Other sightings at Santa Ana included the first Harris’s Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus) of the trip, White-tipped Dove, Groove-billed Ani, Barn Swallow, Black-crested Titmouse, Long-billed Thrasher, a lingering Solitary Vireo, Bronzed Cowbird, Olive Sparrow, and Northern Cardinal. We heard a Dickcissel (Spiza americana) in a sunflower field by the refuge entrance, but failed to see it.

Also at Santa Ana N.W.R. a Giant Toad and a Texas Tortoise (Gopherus berlandieri), a scrubland native of south Texas and northern Mexico.

“We arrived back at Bentsen State Park and I got supper ready while the others birded. At dusk we saw the Elf Owls again and toured the roads. Saw two Pauraques. To bed by 11:15 after a welcome shower.”

A White-eyed Vireo was found during our late afternoon walk. On a tip from Father Tom, we checked the campground in the area of the east restrooms for nesting Tropical Parulas (Setophaga pitiayumi). For each of us, it was another of the five target species for the trip. We heard nothing that resembled this warbler’s song, which sounds very much like that of the Northern Parula with which we were each familiar.

Nightjars are more often seen than heard, so having the opportunity to finish the day watching two Common Pauraques sail across a break in the forest to grab airborne insects was a real treat.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY FOUR—May 24, 1983

“AOK Campground—South of Kingsville, Texas”

“Arose at 6:30 A.M. to the tune of Common Nighthawks. After breakfast, we headed for Harlingen. While driving south we saw six pairs of Black-bellied Whistling Ducks. At Harlingen we phoned Father Tom, who is an expert birder for the area.”

As we drove south to Harlingen, much our 100-mile route was through the Laureles division of the King Ranch, the largest ranch in the United States. It covers over 800,000 acres and is larger than the state of Rhode Island. The road there was as straight as an arrow with wire fences on both sides and scrubland as far as the eye could see. Things really are bigger in Texas.

Once in Harlingen, we did two things no one needs to do anymore:

Today, nearly everyone traveling such distances to find birds is carrying a cellular phone and many can use theirs to access internet sites and databases such as eBird to get current sighting information. Back in 1983, Father Tom Pincelli was a dear friend to birders visiting the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Few places had a person who was willing to answer the phone and field inquiries regarding the latest whereabouts of this or that bird. To remain current, he also had to religiously (forgive me for the pun) collect sighting information from the observers with whom he had contact. For locations elsewhere across the country, a birder in 1983 was happy just to have a phone number for a hotline with a tape-recorded message listing the unusual sightings for its covered region. If you were lucky, the volunteer logging the sightings would be able to update the tape once a week. For those who dialed his number, Father Tom provided an exceptionally personal experience.

Since 1983, Father Tom Pincelli, also known as “Father Bird”, has tirelessly promoted birding and conservation throughout the Lower Rio Grande Valley. His efforts have included hosting a P.B.S. television program and writing columns for local newspapers. He has been instrumental in developing the annual Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival. The public sentiment he has generated for the birding paradise that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley has helped facilitate the acquisition and/or protection of many key parcels of land in the region.

“After receiving information on locations of Tropical Parula, Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, Hook-billed Kite, Brown Jay, and Clay-colored Robin, we went on to check out the Brownsville Airport where we will meet Harold and Steve Thursday noon.”

If we were going to see these five species in the American Birding Association listing area, then we would have to see them in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. All five were target birds for each of us, including Harold who had few other possibilities for new species on the trip. Father Tom provided us with tips for finding each.

I noticed as we began moving around Harlingen and Brownsville that Russ was swiftly getting his bearings—he had been here before and was starting to remember where things were. His ability to navigate his way around allowed us to keep moving and see a lot in a short time.

In Harlingen, we easily found Mourning Doves and the non-native Rock Pigeons, species we see regularly in Pennsylvania. We became more enthusiastic about doves and pigeons soon after when we saw the first of the several other species native to south Texas, the diminutive Inca Dove (Columbina inca), also known as the Mexican Dove.

“Next, to the Brownsville Dump to see the White-necked Ravens — Then to Mrs. Benn’s in Brownsville for the Buff-bellied Hummingbird. Both lifers for Larry.”

For birders wanting to see a White-necked Raven in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the Brownsville Dump was the place to go. With very little effort—excluding a trip of nearly 2,000 miles to get there—we found them. Today, birders still go to the Brownsville Dump to find White-necked Ravens, though the dump is now called the Brownsville Landfill and the bird is known as the Chihuahuan Raven (Corvus cryptoleucus).

Mrs. Benn’s home was in a verdant residential neighborhood in Brownsville. She welcomed birders to come and see the Buff-bellied Hummingbirds that visited her feeder filled with sugar water. I don’t recall whether or not she kept a guest book for visitors to sign, but if she did, it would have included hundreds—maybe thousands—of names of people from all over North America who came to her garden to get a look at a Buff-bellied Hummingbird. After arriving, we waited a short time and sure enough, we watched a Buff-bellied Hummingbird (Amazilia yucatanensis) sipping Mrs. Benn’s home-brewed nectar from her glass feeder. This emerald hummingbird is primarily a Mexican species with a breeding range that extends north into the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. When not breeding, a few will wander north and east along the Gulf Coastal Plain as far as Florida.

Other finds at Mrs Benn’s included White-winged Dove (Zenaida asiatica), Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens), Brown-crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus tyrannulus), and Black-crested Titmouse (Baeolophus atricristatus), a species also known as Mexican Titmouse.

The Lower Rio Grande Valley from Rio Grande City east to the Gulf of Mexico is actually the river’s outflow delta. At least six historic channels have been delineated in Texas on the north side of the river’s present-day course. An equal number may exist south of the border in Mexico. Hundreds of oxbow lakes known as “resacas” mark the paths of the former channels through the delta. Many resacas are the centerpieces of parks, wildlife refuges, and housing developments. Still others are barely detectable after being buried in silt deposits left by the meandering river. Channelization, land disturbances related to agriculture, and a boom in urbanization throughout the valley have disconnected many of the most recently formed resacas from the river’s floodplain, preventing them from absorbing the impact of high-water events. These alterations to natural morphology can severely aggravate flooding and water pollution problems.

“On to Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. We walked to Pintail Lake and saw 6 Black-bellied Whistling Ducks and 2 Mississippi Kites and 1 Pied-billed Grebe. We drove the route thru the park with great results—Anhingas, Least Grebe, and more Black-bellied Whistling Ducks.

Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge on the Rio Grande is not only a birder’s mecca, 300 species of butterflies have been identified there. That’s half the species known to occur in the United States! Its subtropical riparian forest and resaca lakes provide habitat for hundreds of migratory and resident bird species including many Central and South American species that reach the northern limit of their range in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Two endangered cats occur in the park—the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and the Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi).

We saw no cats at Santa Ana, but did quite well with the birds. Our list included the species listed above plus Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis); Louisiana Heron, now known as Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor); Plain Chachalacas; Purple Gallinule; Common Gallinule (Gallinula galeata); American Coot; Killdeer; Greater Yellowlegs; the coastal Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla); and its close relative of the central flyway and continental interior, the Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan). Others finds were White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, Inca Dove, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Ladder-backed Woodpecker (Dryobates scalaris), Brown-crested Flycatcher, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and House Sparrow. A real standout was the colorful Green Jay (Cyanocorax luxosus), yet another tropical Central American species found north only as far as the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

“We were unlucky not to find a campground at McAllen, so we went on to Bentsen State Park where we got a camp spot. After a sauerkraut supper, we birded till dark, then showered and wrote up the log. Very hot today.”

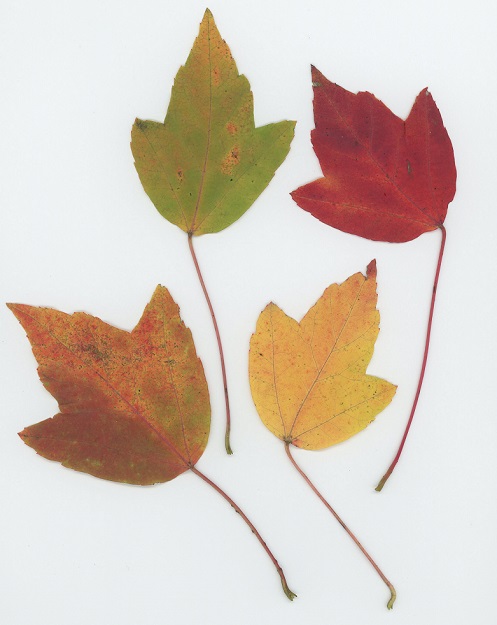

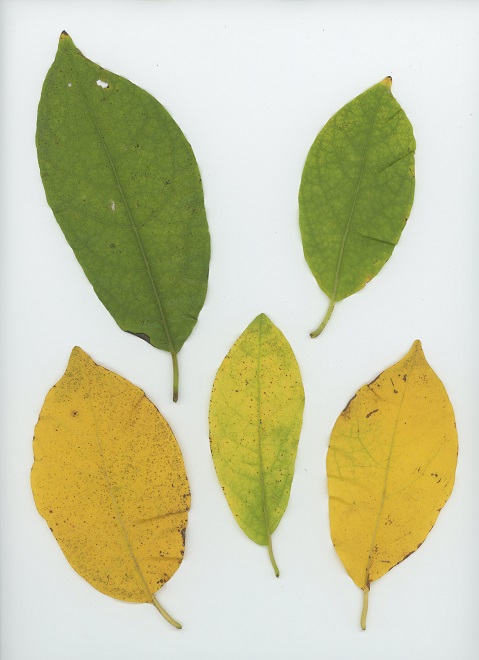

Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, like the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, is located along the Rio Grande river and features dense subtropical riparian forest that grows in the naturally-deposited silt levees of the floodplain surrounding several lake-like oxbow resacas. Montezuma Bald Cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) is a native specialty found there but nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley. During our visit, we marveled at the epiphyte Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) adorning many of the more massive trees in the park. Willows lined much of the river shoreline.

Over time, flood control projects such as man-made dams, drainage ditches, and levees have impaired stormwater capture and aquifer recharge in the floodplain. These alterations to watershed hydrology have resulted in drier soils in many sections of the Lower Rio Grande Valley’s riparian forests. Where drier conditions persist, xeric (dry soil) scrubland plants are slowly overtaking the moisture-dependent species. As a result, the park’s woodlands are composed of trees with a variety of microclimatic requirements—Anaqua (Ehretia anacua), Cedar Elm (Ulmus crassifolia), Texas Ebony (Ebenopsis ebano), hackberry, mesquite, Mexican Ash (Fraxinus berlandieriana), retama, and tepeguaje are the principle species. The park’s subtropical Texas Wild Olive (Cordia boissieri) grows in the wild nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

While a majority of birders visiting Benten-Rio Grande State Park come to see the more tropical specialties of the riparian woods, searching the brushy habitat of the park’s scrubland can afford one the opportunity to see species typical of the southwestern United States and deserts of Mexico. This scrubland of the Lower Rio Grande Valley is part of the Tamaulipan Mezquital ecoregion, an area of xeric (dry soil) shrublands and deserts that extends northwest from the delta through most of south Texas and into the bordering provinces of northeastern Mexico.

Our campsite was located in prime birding habitat. We were a short walk away from one of the park’s flooded oxbow resacas and vegetation was thick along the roadsides. It was no surprise that the place abounded with birds. An evening stroll yielded Plain Chachalaca, White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, White-fronted Dove, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Brown-crested Flycatcher, Green Jay, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and Bronzed Cowbird (Molothrus aeneus). At nightfall, we listened to the calls of an Eastern Screech Owl (Megascops asio), Common Nighthawks, and Common Pauraque (Nyctidromus albicollis), a nightjar of Central and South America that nests only as far north as the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The Common Pauraque is the tropical counterpart of the Eastern Whip-poor-will, a Neotropical migrant that nests in scattered forest locations throughout eastern North America.

I would note that we saw no “snowbirds”—long-term vacationers from the northern states and Canada who fill the park through the cooler months of fall, winter, and spring. They were gone for the summer. But for a few other friendly folks, we had the entire campground to ourselves for the duration of our stay.

This linear grove of mature trees, many of them nearly one hundred years old, is a planting of native White Oaks (Quercus alba) and Swamp White Oaks (Quercus bicolor).

Imagine the benefit of trees like this along that section of stream you’re mowing or grazing right now. The Swamp White Oak in particular thrives in wet soils and is available now for just a couple of bucks per tree from several of the lower Susquehanna’s County Conservation District Tree Sales. These and other trees and shrubs planted along creeks and rivers to create a riparian buffer help reduce sediment and nutrient pollution. In addition, these vegetated borders protect against soil erosion, they provide shade to otherwise sun-scorched waters, and they provide essential wildlife habitat. What’s not to love?

The following native species make great companions for Swamp White Oaks in a lowland setting and are available at bargain prices from one or more of the County Conservation District Tree Sales now underway…

So don’t mow, do something positive and plant a buffer!

Act now to order your plants because deadlines are approaching fast. For links to the County Conservation District Tree Sales in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, see our February 18th post.

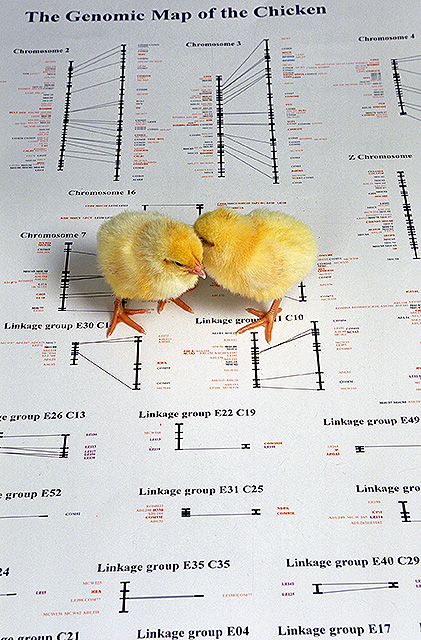

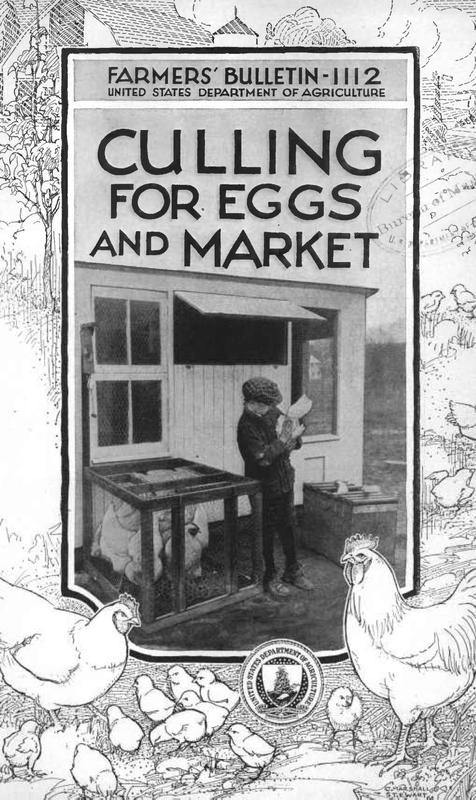

Looks like I’m gonna be in the doghouse again—this time by way of the hen house. But why should I care? Here we go.

A few weeks ago, back when eggs were still selling for less than five dollars a dozen, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture renewed calls for owners and caretakers of outdoor flocks of domestic poultry (backyard chickens) to keep their birds indoors to protect them from the spread of bird flu—specifically “Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza” (H.P.A.I.). At least one story edited and broadcast by a Susquehanna valley news outlet gave the impression that “vultures and hawks” are responsible for the spread of avian flu in chickens. To see if recent history supports such a deduction, let’s have a look at the U.S.D.A.’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s 2022-2023 list of the detection of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in birds affected in counties of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed in Pennsylvania.

This listing includes date of detection, county of collection, type/species of bird, and number of birds affected. WOAH (World Organization for Animal Health) birds include backyard poultry, game birds raised for eventual release, domestic pet species, etc.

12/30/2022 Adams Black Vulture

12/15/2022 Lancaster Canada Goose

12/15/2022 Lebanon Black Vulture

12/15/2022 Adams Black Vulture (3)

11/8/2022 Cumberland Black Vulture (4)

11/4/2022 Dauphin WOAH Non-Poultry (130)

10/19/2022 Dauphin Captive Wild Rhea (4)

10/17/2022 Adams Commercial Turkey (15,100)

10/11/2022 Adams WOAH Poultry (2,800)

9/30/2022 Lancaster Mallard

9/30/2022 Lancaster Mallard

9/29/2022 Lancaster WOAH Non-Poultry (180)

9/29/2022 York Commercial Turkey (25,900)

8/24/2022 Dauphin Captive Wild Crane

7/15/2022 Lancaster Great Horned Owl

7/15/2022 York Bald Eagle

7/15/2022 Dauphin Bald Eagle

6/16/2022 Dauphin Black Vulture

6/16/2022 Dauphin Black Vulture (4)

5/31/2022 Lancaster Black Vulture (2)

5/31/2022 Lancaster Black Vulture

5/10/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (72,300)

4/29/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Duck (19,300)

4/27/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Broiler (18,100)

4/26/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (307,400)

4/22/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Broiler (50,300)

4/20/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (1,127,700)

4/20/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (879,400)

4/15/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (1,380,500)

In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, it’s pretty obvious that the outbreak of avian flu got its foothold inside some of the area’s big commercial poultry houses. Common sense tells us that hawks, vultures, and other birds didn’t migrate north into the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed carrying bird flu, then kick in the doors of the enclosed hen houses to infect the flocks of chickens therein. Anyone paying attention during these past three years knows that isolation and quarantine are practices more easily proposed than sustained. Human footprints are all over the introduction of this infection into these enormous flocks. Simply put, men don’t wipe their feet when no one is watching! The outbreak of bird flu in these large operations was brought under control quickly, but not until teams of state and federal experts arrived to assure proper sanitary and isolation practices were being implemented and used religiously to prevent contaminated equipment, clothing, vehicles, feed deliveries, and feet from transporting virus to unaffected facilities. Large poultry houses aren’t ideal enclosures with absolute capabilities for excluding or containing viruses and other pathogens. Exhaust systems often blow feathers and waste particulates into the air surrounding these sites and present the opportunity for flu to be transported by wind or service vehicles and other conveyances that pass through contaminated ground then move on to other sites—both commercial and non-commercial. Waste material and birds (both dead and alive) removed from commercial poultry buildings can spread contamination during transport and after deposition. The sheer volume of the potentially infected organic material involved in these large poultry operations makes absolute containment of an outbreak nearly impossible.

Looking at the timeline created by the list of U.S.D.A. detections, the opportunity for bird flu to leave the commercial poultry loop probably happened when wild birds gained access to stored or disposed waste and dead animals from an infected commercial poultry operation. For decades now, many poultry operations have dumped dead birds outside their buildings where they are consumed by carrion-eating mammals, crows, vultures, Bald Eagles, and Red-tailed Hawks. For these species, discarded livestock is one of the few remaining food sources in portions of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where high-intensity farming has eliminated other forms of sustenance. They will travel many miles and gather in unnatural concentrations to feast on these handouts—creating ideal circumstances for the spread of disease.

The sequence of events indicated by the U.S.D.A. list would lead us to infer that vultures and Bald Eagles were quick to find and consume dead birds infected with H5N1—either wild species such as waterfowl or more likely domestic poultry from commercial operations or from infectious backyard flocks that went undetected. As the report shows, Black Vultures in particular seem to be susceptible to morbidity. Their frequent occurrence as victims highlights the need to dispose of potentially infectious poultry carcasses properly—allowing no access for hungry wildlife including scavengers.

The positive test on a Great Horned Owl is an interesting case. While the owl may have consumed an infected wild bird such as a crow, there is the possibility that it consumed or contacted a mammalian scavenger that was carrying the virus. Aside from rodents and other small mammals, Great Horned Owls also prey upon Striped Skunks with some regularity. Most of the dead poultry from flu-infected commercial flocks was buried onsite in rows of above-ground mounds. Skunks sniff the ground for subterranean fare, digging up invertebrates and other food. Buried chickens at a flu disposal site would constitute a feast for these opportunistic foragers. A skunk would have no trouble at all finding at least a few edible scraps at such a site. Then a Great Horned Owl could easily seize and feed upon such a flu virus-contaminated skunk.

Before we proceed, the reader must understand the seldom-stated and never advertised mission of the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture—to protect the state’s agriculture industry. That’s it; that’s the bottom line. Regulation and enforcement of matters under the purview of the agency have their roots in this goal. While they may also protect the public health, animal health, and other niceties, the underlying purpose of their existence in its current manifestation is to protect the agriculture industry(s) as a whole.

This is not a trait unique to the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. It is at the core of many other federal and state agencies as well. Following the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle in 1906, a novel decrying “wage slavery” in the meat packing industry, the federal government took action, not for the purpose of improving the working conditions for labor, but to address the unsanitary food-handling practices described in the book by creating an inspection program to restore consumer confidence in the commercially-processed meat supply so that the industry would not crumble.

Locally, few things make the dairy industry and the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture more nervous than small producers selling “raw milk”. In the days before pasteurization and refrigeration, people were frequently sickened and some even died from drinking bacteria-contaminated “raw milk”. In Pennsylvania, the production and sale of dairy products including “raw milk” is closely regulated and requires a permit. Retention of a permit requires submitting to inspections and passing periodic herd and product testing. Despite the dangers, many consumers continue to buy “raw milk” from farms without permits. These sales are like a ticking time bomb. The bad publicity from an outbreak of food-borne illness traced back to a dairy product—even if it originated in an “outlaw” operation—could decimate sales throughout the industry. Because just one sloppy farm selling “raw milk” could instantly erode consumer confidence and cause an industry-wide collapse of the market resulting in a loss of millions of dollars in sales, it is a deeply concerning issue.

Enter the backyard chicken—a two-fold source of anxiety for the poultry industry and its regulators. Like unregulated meat and dairy products, eggs and meat from backyard poultry flocks are often marketed without being monitored for the pathogens responsible for the transmission of food-borne illness. From the viewpoint of the poultry industry, this situation poses a human health risk that in the event of an outbreak, could erode consumer confidence, not only in homegrown organic and free-range products, but in the commercial line of products as well. Consumers can be very reactive upon hearing news of an outbreak, recalling few details other than “the fowl is foul”— then refraining from buying poultry products. The second and currently most concerning source of trepidation among members of the poultry industry though is the threat of avian flu and other diseases being harbored in and transmitted via flocks of backyard birds.

The Green Revolution, the post-World War II initiative that integrated technology into agriculture to increase yields and assure an adequate food supply for the growing global population, brought changes to the way farmers raised poultry for market. Small-scale poultry husbandry slowly disappeared from many farms. Instead, commercial operations concentrated birds into progressively-larger indoor flocks to provide economy of scale. Over time, genetics and nutrition science have provided the American consumer with a line of readily available high-quality poultry products at an inexpensive price. Within these large-scale operations, poultry health is closely monitored. Though these enclosures may house hundreds of thousands of birds, the strategy during an outbreak of communicable disease is to contain an outbreak to the flock therein, writing it off so to speak to prevent the pathogens from finding their way into the remainder of the population in a geographic area, thus saving the industry at the expense of the contents of a single operation. Adherence to effective biosecurity practices can contain outbreaks in this way.

The renewed popularity of backyard poultry is a reversal of the decades-long trend towards reliance on ever-larger indoor operations for the production of birds and eggs. But backyard flocks may make less-than-ideal neighbors for commercial operations, particularly when birds are left to roam outdoors. Visitors to properties with roaming chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys may pick up contamination on their shoes, clothing, tires, and equipment, then transmit the pathogenic material to flocks at other sites they visit without ever knowing it. Even the letter carrier can carry virus from a mud puddle on an infected farm to a grazing area on a previously unaffected one. Unlike commercial operations, hobby farms frequently buy, sell, and trade livestock and eggs without regard to disease transmission. The rate of infection in these operations is always something of a mystery. No state or county permits are required for keeping small numbers of poultry and outbreaks like avian flu are seldom reported by caretakers of flocks of home-raised birds, though their occurrence among them may be widespread. The potential for pathogens like avian flu virus circulating long-term among flocks of backyard poultry in close proximity to commercial houses is a real threat to the industry.

There are a variety of motivations for tending backyard poultry. While for some it is merely a form of pet keeping, others are more serious about the practice—raising and breeding exotic varieties for show and trade. Increasingly, backyard flocks are being established by people seeking to provide their own source of eggs or meat. For those with larger home operations, supplemental income is derived from selling their surplus poultry products. Many of these backyard enthusiasts are part of a movement founded on the belief that, in comparison to commercially reared birds, their poultry is raised under healthier and more humane conditions by roaming outdoors. Organic operators believe their eggs and meat are safer for consumption—produced without the use of chemicals. For the movement’s most dedicated “true believers”, the big poultry industry is the antagonist and homegrown fowl is the only hope. It’s similar to the perspective members of the “raw milk” movement have toward pasteurized milk. True believers are often willing to risk their health and well-being for the sake of the cause, so questioning the validity of their movement can render a skeptic persona non grata.

For the consumer, the question arises, “Are eggs and poultry from the small-scale operations better?”

While many health-conscious animal-friendly consumers would agree to support the small producer from the local farm ahead of big business, the reality of supplying food for the masses requires the economy of scale. The billions of people in the world can’t be fed using small-scale and/or organic growing methods. The Green Revolution has provided record-high yields by incorporating herbicides, insecticides, plastic, and genetic modification into agriculture. To protect livestock and improve productivity, enormous indoor operations are increasingly common. Current economics tell the story—organic production can’t keep up with demand, that’s why the prices for items labelled organic are so much higher.

To the consumer, buying poultry raised outdoors is an appealing option. Compared to livestock crowded into buildings, they feel good about choosing products from small operations where birds roam free and happy in the sunshine.

But is the quality really better? Some research indicates not. Salmonella outbreaks have been traced back to poultry meat sourced from small unregulated operations. Studies have found dioxins in eggs produced by hens left to forage outdoors. The common practice of burning trash can generate a quantity of ash sufficient to contaminate soils with dioxins, chemical compounds which persist in the environment and in the fatty tissue of animals for years. The presence of elevated levels of dioxins in eggs from outdoor grazing operations may pose a potential consumer confidence liability for the entire egg industry.

Birds raised or kept in an outdoor zoo or backyard poultry setting can be susceptible to viruses and other pathogens when wild birds including vultures and hawks become attracted to the captives’ food and water when it is placed in an accessible location. In addition, hunting and scavenging birds are opportunistic— attracted to potential food animals when they perceive vulnerability. Selective breeding under domestication has rendered food poultry fat, dumb, and too genetically impaired for survival in the wild. These weaknesses instantly arouse the curiosity of raptors and other predators whose function in the food web is to maintain a healthy population of animals at lower tiers of the food chain by selectively consuming the sickly and weak. In settings such as those created by high-intensity agriculture and urbanization, wild birds may find the potential food sources offered by outdoor zoos and backyard poultry irresistible. As a result they may perch, loaf, and linger around these locations—potentially exposing the captive birds to their droppings and transmission of bird flu and other diseases.

While outdoor poultry operations usually raise far fewer birds than their commercial counterparts, their animals are still kept in densities high enough to promote the rapid spread of microbiological diseases. Clusters of outdoor flocks can become a reservoir of pathogens with the capability of repeatedly circulating disease into populations of wild birds and even into commercial poultry operations—threatening the industry and food supply for millions of people. For this reason, state and federal agencies are encouraging operators to keep backyard poultry indoors—segregated from natural and anthropogenic disease vectors and conveyances that might otherwise visit and interact with the flock.

The hobby farmer, the homesteader, the pet keeper, and the consumer seldom realize what the modern farmer is coming to know—domestic livestock must be segregated from the sources of contamination and disease that occur outdoors. Adherence to this simple concept helps assure improved health for the animals and a safer food supply for consumers. In the future, outdoor production of domestic animals, particularly those used as a food supply, is likely to be classified as an outdated and antiquated form of animal husbandry.

If there are three things the world learned from the SARS CoV-2 (Covid-19) epidemic, it’s that 1) eating or handling bush meat can bring unwanted surprises, 2) dense populations of very mobile humans are ideal mediums for uncontrolled transmission of disease, and 3) quarantine is easier said than done.

If you think viruses are bad, you don’t even want to know about prions. Prions are a prime example of why now is a good time to begin housing domestic animals, including pets, indoors to segregate them from wildlife. And prions are a good example of why we really ought to think twice about relying on wild animals as a source of food. Prions may make us completely rethink the way we interact with animals of any kind—but we had better do our thinking fast because prions turn the brains of their victims into Swiss cheese.

Diseases caused by prions are rapidly progressing neurodegenerative disorders for which there is no cure. Prions are an abnormal isoform of a cellular glycoprotein. They are currently rare, but prions, because they are not living entities, possess the ability to begin accumulating in the environment. They not only remain in detritus left behind by the decaying carcasses of afflicted animals, but can also be shed in manure—entering soils and becoming more and more prevalent over time. Some are speculating that they could wind up being man’s downfall.

The Centers for Disease Control lists these human afflictions caused by prions…

The Centers for Disease Control lists these prion-caused ailments of other animals…

SOURCES

Schoeters, Greet, and Ron Hoogenboom. 2006. Contamination of Free-range Chicken Eggs with Dioxins and Dioxin-like Polychlorinated Biphenyls. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. (10):908-14.

Szczepan, Mikolajczyk, Marek Pajurek, Malgorzata Warenik-Bany, and Sebastian Maszewski. 2021. Environmental Contamination of Free-range Hen with Dioxin. Journal of Veterinary Research. 65(2):225-229.

U.S.D.A. Animal and Plant Inspection Service. 2022 Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-2022/2022-hpai-commercial-backyard-flocks as accessed January 14, 2023.

U.S.D.A. Animal and Plant Inspection Service. 2022 Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-2022/2022-hpai-wild-birds as accessed January 14, 2023.

Here are several of the Golden Eagles seen migrating in this morning’s stiff north-northwest wind along Second Mountain in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania.

To learn more about determining the age of a Golden Eagle on the wing, click the “Golden Eagle Aging Chart” tab at the top of this page, then get to a hawk watch and have a look.

With colder temperatures arriving on gusty northwest winds, the next couple of days will be ideal for seeing migrating birds of prey along the ridges of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. It’s still peak time for movements of four of our largest species: Red-shouldered Hawk, Red-tailed Hawk, Bald Eagle, and Golden Eagle—so let’s grab our binoculars and have a look!

Be certain to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper” tab at the top of this page to select a lookout for observing and enjoying the passage of these spectacular late-season raptors. To improve your chances of seeing a Golden Eagle, visit a counting station in the Ridge and Valley Province, but do bundle up—it’s cold on those mountaintops.

Flights of southbound Broad-winged Hawks have joined those of other Neotropical migrants to thrill observers with spectacular numbers. In recent days, thousands have been seen and counted at many of the regions hawkwatching stations. Now is the time to check it out!

Other diurnal migrants are on the move as well…

Adding to the diversity of sightings, there are these diurnal raptors arriving in the area right now…

For more information and directions to places where you can observe migrating hawks and other birds, be certain to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper” tab at the top of this page.

It’s that time of year—Snow Geese on their northbound migration, more than 100,000 of them, have arrived for a stopover at the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties. Get there now to see scenes like these in person…

Why are there dozens of people with enormous lenses on complicated cameras atop sturdy tripods gathered at Fisherman’s Park below the Conowingo Dam on the lower Susquehanna River in Maryland? It’s Bald Eagle time, that’s why. Here are some photos from the scene, taken just two days ago.

To reach Exelon Energy’s Conowingo Fisherman’s Park from Rising Sun, Maryland, follow U.S. Route 1 south across the Conowingo Dam, then turn left onto Shuresville Road, then make a sharp left onto Shureslanding Road. Drive down the hill to the parking area along the river. The park’s address is 2569 Shureslanding Road, Darlington, Maryland.

Do make an excursion to the lower Susquehanna at Conowingo soon. To avoid crowds and parking congestion, plan to visit on a weekday. You’ll want warm clothing, binoculars, and a camera too.