A Pre-dawn Thunderstorm and a Fallout of Migrating Birds

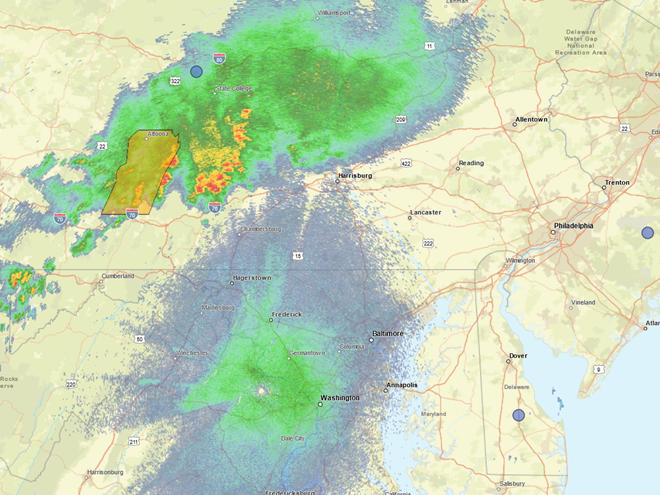

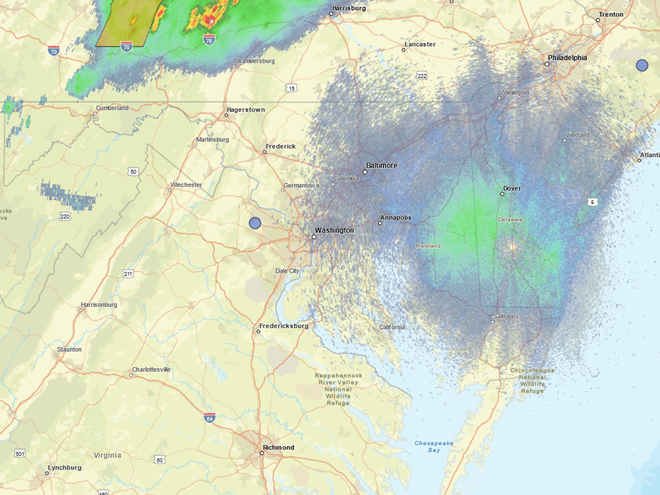

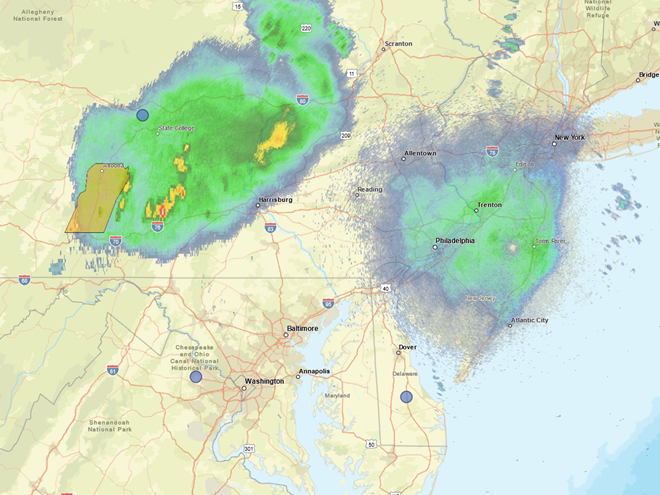

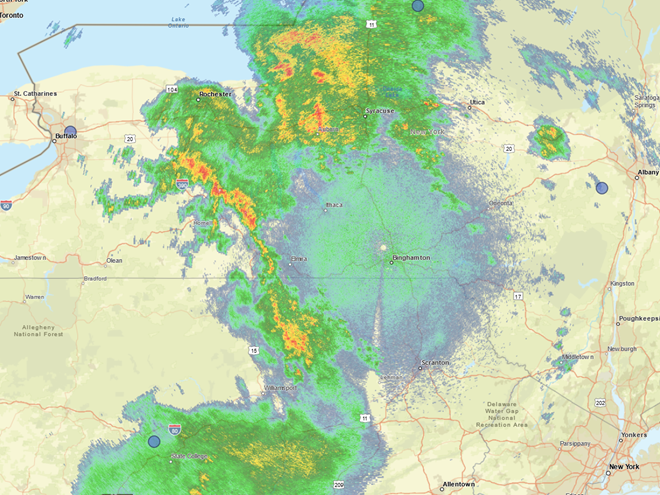

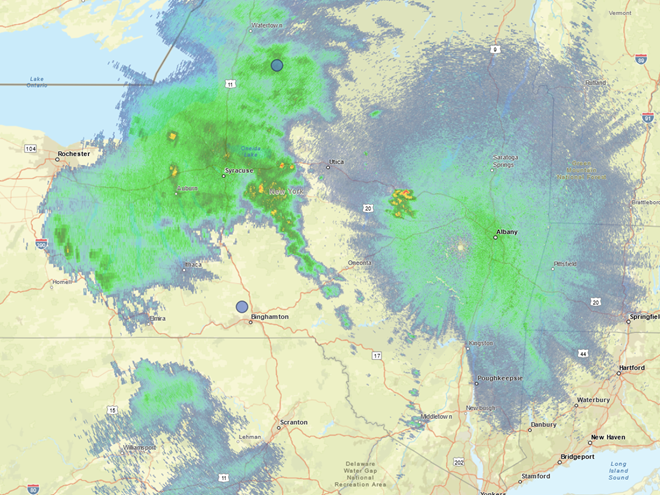

In recent days, the peak northbound push of migratory birds that includes the majority of our colorful Neotropical species has been slowed to a trickle by the presence of rain, fog, and low overcast throughout the Mid-Atlantic States. Following sunset last evening, the nocturnal flight resumed—only to be grounded this morning during the pre-dawn hours by the west-to-east passage of a fast-moving line of strong thundershowers. The NOAA/National Weather Service images that follow show the thunderstorms as well as returns created by thousands of migrating birds as they pass through the Doppler Radar coverage areas that surround the lower Susquehanna valley.

Just after 4 A.M., flashes of lightning in rapid succession repeatedly illuminated the sky over susquehannawildlife.net headquarters. Despite the rumbles of thunder and the din of noises typical for our urban setting, the call notes of nocturnal migrants could be heard as these birds descended in search of a suitable place to make landfall and seek shelter from the storm. At least one Wood Thrush and a Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus) were in the mix of species passing overhead. A short time later at daybreak, a Great Crested Flycatcher was heard calling from a stand of nearby trees and a White-crowned Sparrow was seen in the garden searching for food. None of these aforementioned birds is regular here at our little oasis, so it appears that a significant and abrupt fallout has occurred.

Looks like a good day to take the camera for a walk. Away we go!

There’s obviously more spring migration to come, so do make an effort to visit an array of habitats during the coming weeks to see and hear the wide variety of birds, including the spectacular Neotropical species, that visit the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed each May. You won’t regret it!

The Fog of a January Thaw

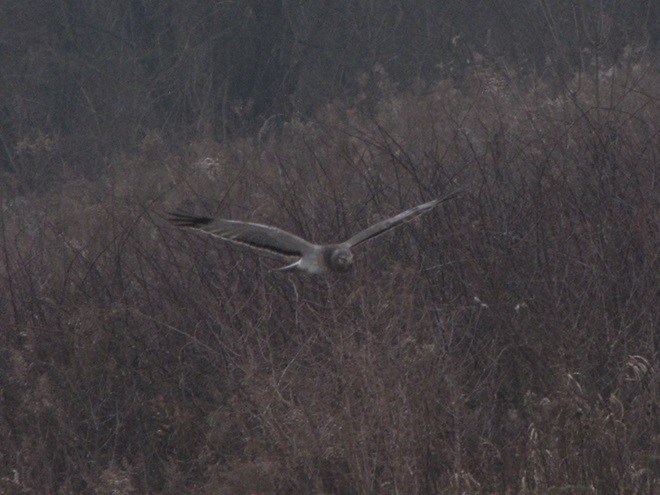

As week-old snow and ice slowly disappears from the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed landscape, we ventured out to see what might be lurking in the dense clouds of fog that for more than two days now have accompanied a mid-winter warm spell.

If scenes of a January thaw begin to awaken your hopes and aspirations for all things spring, then you’ll appreciate this pair of closing photographs…

Time to Eat

A glimpse of the rowdy guests crowding the Thanksgiving Day dinner table at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters…

A Visit to a Beaver Pond

To pass the afternoon, we sat quietly along the edge of a pond created recently by North American Beavers (Castor canadensis). They first constructed their dam on this small stream about five years ago. Since then, a flourishing wetland has become established. Have a look.

Isn’t that amazing? North American Beavers build and maintain what human engineers struggle to master—dams and ponds that reduce pollution, allow fish passage, and support self-sustaining ecosystems. Want to clean up the streams and floodplains of your local watershed? Let the beavers do the job!

Peanuts! Get Your Peanuts!

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

The Gasoline and Gunpowder Gang’s Second-biggest Holiday of the Year

For members of the gasoline and gunpowder gang in Pennsylvania, the coming two weeks are the second-biggest holiday of the year. Cloaked in ceremonial orange, worshipers of the White-tailed Deity are making their annual pilgrimage into the great outdoors to beat the bushes in search of their idol. For the fortunate among the faithful, their devotion culminates in a testosterone/adrenaline-charged sacrifice of the supreme being.

Remember, emotions run high during this blood-letting festival—sometimes overwhelming secular attributes like logic and rational decision-making. You don’t want to be in the crossfire—so stay out of the woods!

Photo of the Day

Emergence of the Turtles

Along the lower Susquehanna, an unseasonably mild day in early spring can provide an observer with the opportunity to witness an annual spectacle seldom seen by the average visitor to the river—concentrations of dozens, sometimes hundreds, of turtles as they emerge from their winter slumber to bathe in the year’s first surge of warm air and sunshine.

Photo of the Day

Five Best Values for Feeding Birds

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

Photo of the Day

Digging In

If you visit the shores of the Susquehanna River during the warmer months of the year, there’s a pretty good probability that you’ll be taking a visitor along home with you. Not to worry, it won’t raid the icebox or change the television channels when you leave the room to get a snack. It won’t put you in the doghouse with the landlord for having a forbidden pet. As a matter of fact, you may not even notice your new companion. Sure enough though, it’s there, crawling through the luxurious warm fabric of your clothing and seeking out a good place to dig in and chow down. O.K., so now you’re worried.

Ticks, particularly the American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis), are widespread in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Like spiders, they are arachnids. They have a four-stage life cycle (egg-larva-nymph-adult) which, in the case of D. variabilis, requires a minimum of two months to complete. Females lay up to 6,500 eggs on the ground. Then the fun begins as the larvae with any hope of survival must attach to a small mammal to feed. They can survive for almost a year before finding a host. After a successful hookup and subsequent blood feast of up to two weeks duration, the larva drops to the ground, molts into a nymph, and finds another small mammal, usually a bit bigger this time, to feed upon. A nymph can survive for up to six months before needing to feed. Finding the second host, the nymph feeds for 3 to 10 days, then drops to the ground to molt into an adult. Adult American Dog Ticks can endure up to two years without feeding on a host. The adults mate and feed on larger mammals such as deer and domestic animals including, of course, dogs. After a blood meal of five days to two weeks duration, the adult female tick drops to the ground to lay eggs and initiate a new generation.

The American Dog Tick is renowned as a carrier of the Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever bacteria (Rickettsia rickettsii). The bacteria is vectored by the ticks from rodents to dogs and humans. The adult tick must be attached to the victim for a minimum of six to eight hours to transmit the pathogen. A rash spreading from the wrists and the ankles to other portions of the body begins two to fourteen days after infection.

Tularemia, caused by the bacteria Francisella tularensis, can be passed by the American Dog Tick. Symptoms can appear in three to twenty-one days and include chills, fever, and inflammation of the lymph nodes.

American Dog Ticks which attach to dogs, particularly near the neck, and are left in place to feed and engorge themselves for longer than five days can cause Canine Tick Paralysis. Symptoms usually begin to subside only after a recovery period following removal of the arachnid.

The American Dog Tick is exposed to Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria responsible for Lyme Disease, however, transmittal of this pathogen is by the smaller Deer Tick (Ixodes scapularis), also known as the Black-legged Tick. The Deer Tick is not presently common at Conewago Falls. In the adjacent uplands, it is widespread and is carrying Lyme Disease where the White-tailed Deity (Odocoileus virginianus), the preferred host for the ticks, is found along with mice and other small rodents, the source of B. burgdorferi bacteria. The Deer Tick easily escapes notice and cases of Lyme Disease are frequent, so vigilance is necessary.

SOURCES

Chan, Wai-Han, and Kaufman, Phillip. 2008. American Dog Tick. University of Florida Featured Creatures website entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/urban/medical/american_dog_tick.htm as accessed July 30, 2017.