More Migrating Birds

As waves of wet weather persistently roll through the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the tide of northbound migrants continues. Here are few of today’s highlights…

A Pre-dawn Thunderstorm and a Fallout of Migrating Birds

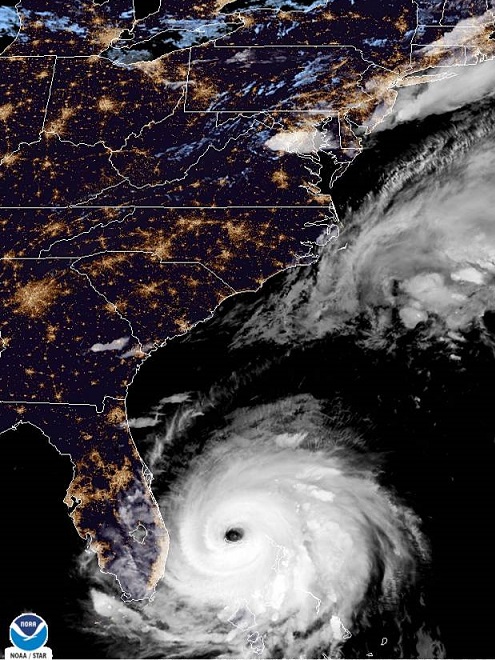

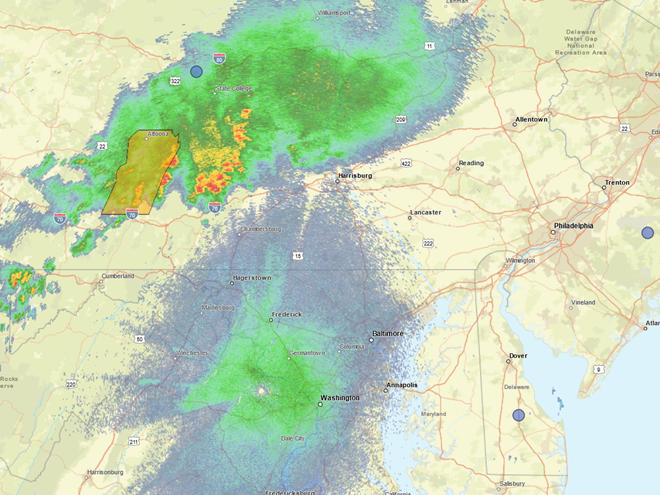

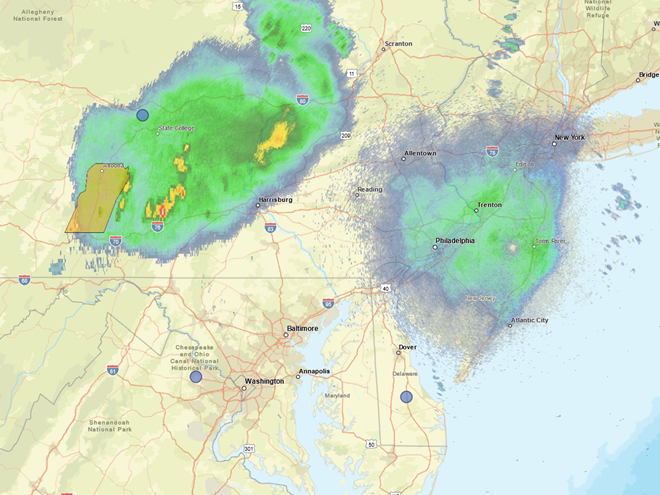

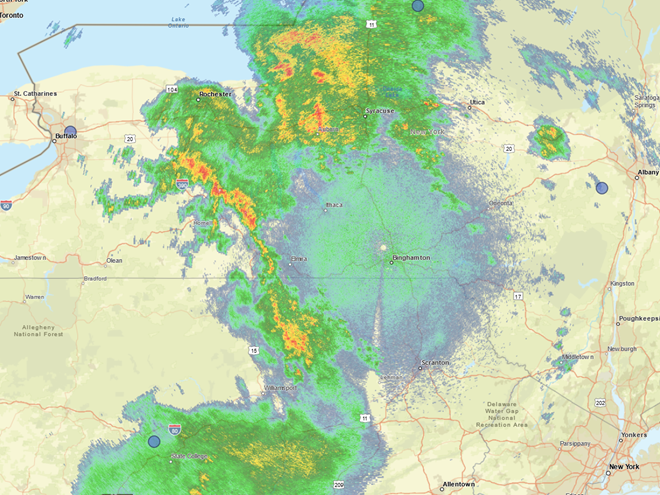

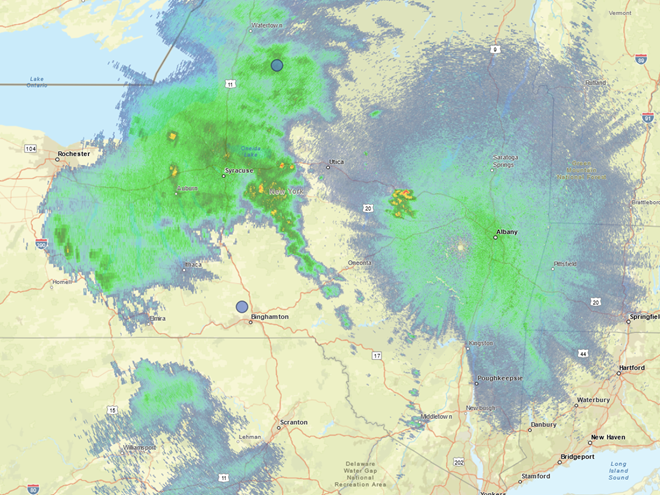

In recent days, the peak northbound push of migratory birds that includes the majority of our colorful Neotropical species has been slowed to a trickle by the presence of rain, fog, and low overcast throughout the Mid-Atlantic States. Following sunset last evening, the nocturnal flight resumed—only to be grounded this morning during the pre-dawn hours by the west-to-east passage of a fast-moving line of strong thundershowers. The NOAA/National Weather Service images that follow show the thunderstorms as well as returns created by thousands of migrating birds as they pass through the Doppler Radar coverage areas that surround the lower Susquehanna valley.

Just after 4 A.M., flashes of lightning in rapid succession repeatedly illuminated the sky over susquehannawildlife.net headquarters. Despite the rumbles of thunder and the din of noises typical for our urban setting, the call notes of nocturnal migrants could be heard as these birds descended in search of a suitable place to make landfall and seek shelter from the storm. At least one Wood Thrush and a Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus) were in the mix of species passing overhead. A short time later at daybreak, a Great Crested Flycatcher was heard calling from a stand of nearby trees and a White-crowned Sparrow was seen in the garden searching for food. None of these aforementioned birds is regular here at our little oasis, so it appears that a significant and abrupt fallout has occurred.

Looks like a good day to take the camera for a walk. Away we go!

There’s obviously more spring migration to come, so do make an effort to visit an array of habitats during the coming weeks to see and hear the wide variety of birds, including the spectacular Neotropical species, that visit the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed each May. You won’t regret it!

Photo of the Day

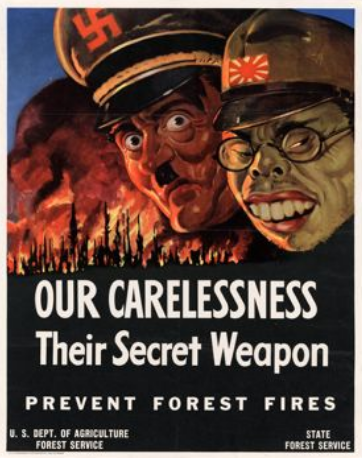

Prescribed Fire: Controlled Burns for Forest and Non-forest Habitats

Homo sapiens owes much of its success as a species to an acquired knowledge of how to make, control, and utilize fire. Using fire to convert the energy stored in combustible materials into light and heat has enabled humankind to expand its range throughout the globe. Indeed, humans in their furless incomplete mammalian state may have never been able to expand their populations outside of tropical latitudes without mastery of fire. It is fire that has enabled man to exploit more of the earth’s resources than any other species. From cooking otherwise unpalatable foods to powering the modern industrial society, fire has set man apart from the rest of the natural world.

In our modern civilizations, we generally look at the unplanned outbreak of fire as a catastrophe requiring our immediate intercession. A building fire, for example, is extinguished as quickly as possible to save lives and property. And fires detected in fields, brush, and woodlands are promptly controlled to prevent their exponential growth. But has fire gone to our heads? Do we have an anthropocentric view of fire? Aren’t there naturally occurring fires that are essential to the health of some of the world’s ecosystems? And to our own safety? Indeed there are. And many species and the ecosystems they inhabit rely on the periodic occurrence of fire to maintain their health and vigor.

Man has been availed of the direct benefits of fire for possibly 40,000 years or more. Here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the earliest humans arrived as early as 12,000 years ago—already possessing skills for using fire. Native plants and animals on the other hand, have been part of the ever-changing mix of ecosystems found here for a much longer period of time—millions to tens of millions of years. Many terrestrial native species are adapted to the periodic occurrence of fire. Some, in fact, require it. Most upland ecosystems need an occasional dose of fire, usually ignited by lightning (though volcanism and incoming cosmic projectiles are rare possibilities), to regenerate vegetation, release nutrients, and maintain certain non-climax habitat types.

But much of our region has been deprived of natural-type fires since the time of the clearcutting of the virgin forests during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This absence of a natural fire cycle has contributed to degradation and/or elimination of many forest and non-forest habitats. Without fire, a dangerous stockpile of combustible debris has been collecting, season after season, in some areas for a hundred years or more. Lacking periodic fires or sufficient moisture to sustain prompt decomposition of dead material, wildlands can accumulate enough leaf litter, thatch, dry brush, tinder, and fallen wood to fuel monumentally large forest fires—fires similar to those recently engulfing some areas of the American west. So elimination of natural fire isn’t just a problem for native plants and animals, its a potential problem for humans as well.

To address the habitat ailments caused by a lack of natural fires, federal, state, and local conservation agencies are adopting the practice of “prescribed fire” as a treatment to restore ecosystem health. A prescribed fire is a controlled burn specifically planned to correct one or more vegetative management problems on a given parcel of land. In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is used to…

-

-

- Eliminate dangerous accumulations of combustible fuels in woodlands.

- Reduce accumulations of dead plant material that may harbor disease.

- Provide top kill to promote oak regeneration.

- Regenerate other targeted species of trees, wildflowers, grasses, and vegetation.

- Kill non-native plants and promote growth of native plants.

- Prevent succession.

- Remove woody growth and thatch from grasslands.

- Promote fire tolerant species of plants and animals.

- Create, enhance, and/or manage specialized habitats.

- Improve habitat for rare species (Regal Fritillary, etc.)

- Recycle nutrients and minerals contained in dead plant material.

-

Let’s look at some examples of prescribed fire being implemented right here in our own neighborhood…

In Pennsylvania, state law provides landowners and crews conducting prescribed fire burns with reduced legal liability when the latter meet certain educational, planning, and operational requirements. This law may help encourage more widespread application of prescribed fire in the state’s forests and other ecosystems where essential periodic fire has been absent for so very long. Currently in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is most frequently being employed by state agencies on state lands—in particular, the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources on State Forests and the Pennsylvania Game Commission on State Game Lands. Prescribed fire is also part of the vegetation management plan at Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation and on the land holdings of the Hershey Trust. Visitors to the nearby Gettysburg National Military Park will also notice prescribed fire being used to maintain the grassland restorations there.

For crews administering prescribed fire burns, late March and early April are a busy time. The relative humidity is often at its lowest level of the year, so the probability of ignition of previous years’ growth is generally at its best. We visited with a crew administering a prescribed fire at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area last week. Have a look…

Prescribed burns aren’t a cure-all for what ails a troubled forest or other ecosystem, but they can be an effective remedy for deficiencies caused by a lack of periodic episodes of naturally occurring fire. They are an important option for modern foresters, wildlife managers, and other conservationists.

Snow Geese, Bald Eagles, and More at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area

To take advantage of this unusually mild late-winter day, observers arrived by the thousands to have a look at an even greater number of migratory birds gathered at the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area. Here are some highlights…

Birds Beginning to Wander

Since Tuesday’s snow storm, the susquehannawiildlife.net headquarters garden continues to bustle with bird activity.

Today, there arrived three species of birds we haven’t seen here since autumn. These birds are, at the very least, beginning to wander in search of food. Then too, these may be individuals creeping slowly north to secure an advantage over later migrants by being the first to establish territories on the most favorable nesting grounds.

They say the early bird gets the worm. More importantly, it gets the most favorable nesting spot. What does the early birder get? He or she gets out of the house and enjoys the action as winter dissolves into the miracle of spring. Do make time to go afield and marvel a bit, won’t you? See you there!

The Fog of a January Thaw

As week-old snow and ice slowly disappears from the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed landscape, we ventured out to see what might be lurking in the dense clouds of fog that for more than two days now have accompanied a mid-winter warm spell.

If scenes of a January thaw begin to awaken your hopes and aspirations for all things spring, then you’ll appreciate this pair of closing photographs…

Birds Along the River’s Edge

Just as bare ground along a plowed road attracts birds in an otherwise snow-covered landscape, a receding river or large stream can provide the same benefit to hungry avians looking for food following a winter storm.

Here is a small sample of some of the species seen during a brief stop along the Susquehanna earlier this week.

Birds of Snow-covered Farmland

When the ground becomes snow covered, it’s hard to imagine anything lives in the vast wide-open expanses of cropland found in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s fertile valleys.

Yet, there is one group of birds that can be found scrounging a living from what little exists after a season of high-intensity farming. Meet the Horned Lark.

If you decide to take a little post-storm trip to look for Horned Larks and Lapland Longspurs, be sure to drive carefully. Do your searching on quiet rural roads with minimal traffic. Stop and park only where line-of-sight and other conditions allow it to be done safely. Use your flashers and check your mirrors often. Think before you stop and park—don’t get stuck or make a muddy mess. And most important of all, be aware that you’re on a roadway—get out of the way of traffic.

If you’re not going out to look for larks and longspurs, we do have a favor to ask of you. Please remember to slow down while you’re driving. Not only is this an accident-prone time of year for people in cars and trucks, it’s a dangerous time for birds and other wildlife too. They’re at greatest peril of getting run over while concentrated along roadsides looking for food following snow storms.

Birds of the Sunny Grasslands

With the earth at perihelion (its closest approach to the sun) and with our home star just 27 degrees above the horizon at midday, bright low-angle light offered the perfect opportunity for doing some wildlife photography today. We visited a couple of grasslands managed by the Pennsylvania Game Commission to see what we could find…

Photos of a Visiting Cooper’s Hawk

While trimming the trees and shrubs in the susquehannawildlife.net garden, it didn’t seem particularly unusual to hear the resident Carolina Chickadees and Carolina Wrens scolding our every move. But after a while, their persistence did seem a bit out of the ordinary, so we took a little break to have a look around…

Here at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, we are visited by Cooper’s Hawks for several days during the late fall and winter each year. The small birds that visit our feeders have plenty of trees, shrubs, vines, and other natural cover in which to hide from raptors and other native predators. We don’t create unnatural concentrations of birds by dumping food all over the place. We try to keep our small birds healthy by sparingly offering fresh seed and other provisions in clean receptacles to provide a supplement to the seeds, fruits, insects, and other foods that occur naturally in the garden. With only a few vulnerable small birds around, the Cooper’s Hawks visit just long enough to cull out our weakest individuals before moving elsewhere. While they’re in our garden, they too are our welcomed guests.

Time to Eat

A glimpse of the rowdy guests crowding the Thanksgiving Day dinner table at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters…

Sparrows in the Thicket

As the annual autumn songbird migration begins to reach its end, native sparrows can be found concentrating in fallow fields, early successional thickets, and brushy margins along forest edges throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Visit native sparrow habitat during mid-to-late November and you have a good chance of seeing these species and more…

If you’re lucky enough to live where non-native House Sparrows won’t overrun your bird feeders, you can offer white millet as a supplement to the wild foods these beautiful sparrows might find in your garden sanctuary. Give it a try!

Some Good Reasons to Postpone Mowing Until Mid-August

Here in a series of photographs are just a handful of the reasons why the land stewards at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area and other properties where conservation and propagation practices are employed delay the mowing of fields composed of cool-season grasses until after August 15 each year.

Right now is a good time to visit Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area to see the effectiveness a delayed mowing schedule can have when applied to fields of cool-season grasses. If you slowly drive, walk, or bicycle the auto tour route on the north side of the lake, you’ll pass through vast areas maintained as cool-season and warm-season grasses and early successional growth—and you’ll have a chance to see these and other grassland birds raising their young. It’s like a trip back in time to see farmlands they way they were during the middle years of the twentieth century.

Berries and More on a Bitter Cold Morning

The annual arrival of hoards of American Robins to devour the fruits found on the various berry-producing shrubs and trees in the garden at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters happened to coincide with this morning’s bitter cold temperatures. Here are photos of some of those hungry robins—plus shots of the handful of other songbirds that joined them for a frosty feeding frenzy.

Photo of the Day

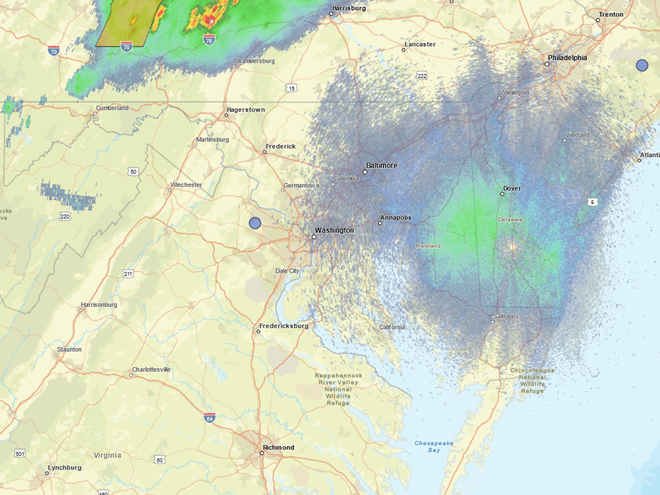

Nocturnal Migrants in Moonlight

Happening right now, in the bright moonlight on a crisp autumn night, there is a massive movement of nocturnally migrating birds indicated on National Weather Service Radar from State College, Pennsylvania. Notice the dense wave crossing the lower Susquehanna River watershed from northeast to southwest. The coming morning may reveal plenty of new arrivals after daybreak. Look for robins, native sparrows, etc.

Five Best Values for Feeding Birds

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

A Visit to Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

Maximum Variety

You’ll want to go for a walk this week. It’s prime time to see birds in all their spring splendor. Colorful Neotropical migrants are moving through in waves to supplement the numerous temperate species that arrived earlier this spring to begin their nesting cycle. Here’s a sample of what you might find this week along a rail-trail, park path, or quiet country road near you—even on a rainy or breezy day.

Slow Down When There’s Snow on the Ground

It’s just common sense to take it easy and drive carefully when snow covers streets and highways. Everyone knows that. But did you know that slowing down when the landscape is blanketed in white can save lives even after the roadways have been cleared?

Following significant snowfalls such as the one earlier this week, birds and other wildlife are attracted to bare ground along the edges of plowed pavement. They are often so preoccupied with the search for food that they ignore approaching cars and trucks until it is too late.

Take a look at the species found today along a one mile stretch of plowed rural roadway in the lower Susquehanna valley.

For many species of wildlife in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the fragmented and impaired state of habitat already challenges their chances of surviving the winter. Snow cover can isolate them from their limited food supplies and force them to roadsides and other dangerous locations to forage. Mauling them with motor vehicles just adds to the escalating tragedy, so do wildlife and yourself a favor—please slow down.

A Visit to Rocky Ridge

Early October is prime time for hawk watching, particularly if you want to have the chance to see the maximum variety of migratory species. In coming days, a few Broad-winged Hawks and Ospreys will still be trickling through while numbers of Sharp-shinned Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks, Northern Harriers, and falcons swell to reach their seasonal peak. Numbers of migrating Red-tailed and Red-shouldered Hawks are increasing during this time and late-season specialties including Golden Eagles can certainly make a surprise early visit.

If you enjoy the outdoors and live in the southernmost portion of the lower Susquehanna valley, Rocky Ridge County Park in the Hellam Hills just northwest of York, Pennsylvania, is a must see. The park consists of oak forest and is owned and managed by the York County Parks Department. It features an official hawk watch site staffed by volunteers and park naturalists. Have a look.

If you’re a nature photographer, you might be interested to know that there are still hundreds of active butterflies in Rocky Ridge’s utility right-of-way. Here are a few.

To see the daily totals for the raptor count at Rocky Ridge Hawk Watch and other hawk watches in North America, and to learn more about each site, be certain to visit hawkcount.org

The Colorful Birds Are Here

You need to get outside and go for a walk. You’ll be sorry if you don’t. It’s prime time to see wildlife in all its glory. The songs and colors of spring are upon us!

If you’re not up to a walk and you just want to go for a slow drive, why not take a trip to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area and visit the managed grasslands on the north side of the refuge. To those of us over fifty, it’s a reminder of how Susquehanna valley farmlands were before the advent of high-intensity agriculture. Take a look at the birds found there right now.

And remember, if you happen to own land and aren’t growing crops on it, put it to good use. Mow less, live more. Mow less, more lives.

Get Away From It All

For those of you who dare to shed that filthy contaminated rag you’ve been told to breathe through so that you might instead get out and enjoy some clean air in a cherished place of solitude, here’s what’s around—go have a look.

The springtime show on the water continues…

Hey, what are those showy flowers?

Wasn’t that refreshing? Now go take a walk.

A Springtime Quiz

The mild winter has apparently minimized weather-related mortality for the local Green Frog population. With temperatures in the seventies throughout the lower Susquehanna valley for this first full day of spring, many recently emerged adults could be seen and, on occasion, heard. Yellow-throated males tested their mating calls—reminding the listener of the sound made by the plucking of a loose banjo string.

If you venture out, keep alert for the migrating birds of late winter and early spring.

If you’re staying close to home, be sure to check out the changing appearance of the birds you see nearby. Some species are losing their drab winter basic plumage and attaining a more colorful summer breeding alternate plumage.

So just how many Green Frogs were there in that first photograph? Here’s the answer.

Happy Spring. For the benefit of everyone’s health, let’s hope that it’s a hot and humid one!

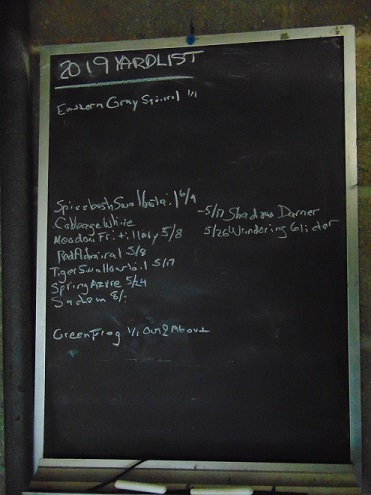

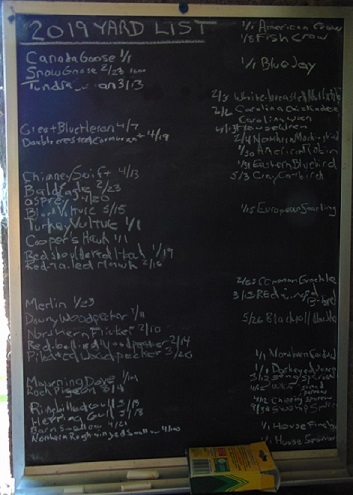

Clean Slate for 2020

Inside the doorway that leads to your editor’s 3,500 square foot garden hangs a small chalkboard upon which he records the common names of the species of birds that are seen there—or from there—during the year. If he remembers to, he records the date when the species was first seen during that particular year. On New Year’s Day, the results from the freshly ended year are transcribed onto a sheet of notebook paper. On the reverse, the names of butterflies, mammals, and other animals that visited the garden are copied from a second chalkboard that hangs nearby. The piece of paper is then inserted into a folder to join those from previous New Year’s Days. The folder then gets placed back into the editor’s desk drawer beneath a circular saw blade and an old scratched up set of sunglasses—so that he knows exactly where to find it if he wishes to.

A quick glance at this year’s list calls to mind a few recollections.

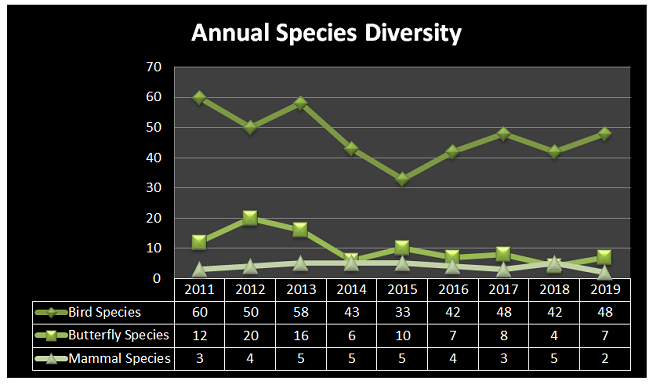

Before putting the folder back into the drawer for another year, the editor decided to count up the species totals on each of the sheets and load them into the chart maker in the computer.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

It appears that, at the very least, the garden habitat has been disconnected from the home ranges of many species by fragmentation. His little oasis is now isolated in a landscape that becomes increasingly hostile to native wildlife with each passing year. The paving of more parking areas, the elimination of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous growth from the large number of rental properties in the area, the alteration of the biology of the nearby stream by hand-fed domestic ducks, light pollution, and the outdoor use of pesticides have all contributed to the separation of the editor’s tiny sanctuary from the travel lanes and core habitats of many of the species that formerly visited, fed, or bred there. In 2019, migrants, particularly “fly-overs”, were nearly the only sightings aside from several woodpeckers, invasive House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and hardy Mourning Doves. Even rascally European Starlings became sporadic in occurrence—imagine that! It was the most lackluster year in memory.

If habitat fragmentation were the sole cause for the downward trend in numbers and species, it would be disappointing, but comprehendible. There would be no cause for greater alarm. It would be a matter of cause and effect. But the problem is more widespread.

Although the editor spent a great deal of time in the garden this year, he was also out and about, traveling hundreds of miles per week through lands on both the east and the west shores of the lower Susquehanna. And on each journey, the number of birds seen could be counted on fingers and toes. A decade earlier, there were thousands of birds in these same locations, particularly during the late summer.

In the lower Susquehanna valley, something has drastically reduced the population of birds during breeding season, post-breeding dispersal, and the staging period preceding autumn migration. In much of the region, their late-spring through summer absence was, in 2019, conspicuous. What happened to the tens of thousands of swallows that used to gather on wires along rural roads in August and September before moving south? The groups of dozens of Eastern Kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus) that did their fly-catching from perches in willows alongside meadows and shorelines—where are they?

Several studies published during the autumn of 2019 have documented and/or predicted losses in bird populations in the eastern half of the United States and elsewhere. These studies looked at data samples collected during recent decades to either arrive at conclusions or project future trends. They cite climate change, the feline infestation, and habitat loss/degradation among the factors contributing to alterations in range, migration, and overall numbers.

There’s not much need for analysis to determine if bird numbers have plummeted in certain Lower Susquehanna Watershed habitats during the aforementioned seasons—the birds are gone. None of these studies documented or forecast such an abrupt decline. Is there a mysterious cause for the loss of the valley’s birds? Did they die off? Is there a disease or chemical killing them or inhibiting their reproduction? Is it global warming? Is it Three Mile Island? Is it plastic straws, wind turbines, or vehicle traffic?

The answer might not be so cryptic. It might be right before our eyes. And we’ll explore it during 2020.

In the meantime, Uncle Ty and I going to the Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg. You should go too. They have lots of food there.

No Need to Hurry

It’s that time of year when one may expect to find migratory Neotropical songbirds feeding among the foliage of trees and shrubs in the forests, woodlots, and thickets of the lower Susquehanna valley.

During a late afternoon stroll through a headwaters forest east of Conewago Falls outside Mount Gretna, I was pleased to finally come upon a noisy gathering of about two dozen birds. It had, previous to that, been a quiet two hours of walking, only the rumble of an approaching thunderstorm punctuated the silence. Among this little flock were some chickadees, robins, Gray Catbirds, an Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus), and a Hairy Woodpecker (Dryobates villosus). Besides the catbirds, there were two other species of Neotropical migrants; both were warblers. No less than six Black-throated Blue Warblers (Setophaga caerulescens) were vying for positions in the trees from which they could investigate the stranger on the footpath below. And among the understory shrubs there were at least as many Ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla) satisfying a similar curiosity.

When they depart the Susquehanna valley, these two warbler species will be southbound for wintering ranges that include Florida, many of the Caribbean Islands, Central America, and, for the Ovenbirds, northern South America. Their flights occur at night. During the breeding season and while migrating, both feed primarily on insects and other arthropods . On the wintering grounds, they will consume some fruit. It is during their time in the tropics that the Black-throated Blue Warbler sometimes visits feeding stations that offer grape jelly, much to the delight of bird enthusiasts.

Black-throated Blue Warblers and Ovenbirds commonly winter on the Florida peninsula and in the Bahamas. With the major tropical cyclone Hurricane Dorian presently ripping through the region, these birds are better off taking their time getting there. There’s no need to hurry. The longer they and the other Neotropical migrants hang around, the more we get to enjoy them anyway. So get out there to see them before they go—and remember to look up.