Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

The rain and clouds have at last departed. With blue skies and sunshine to remind us just how wonderful a spring afternoon can be, we took a stroll at Memorial Lake State Park in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, to look for some migratory birds.

What? You thought we were gonna drop in on Maryland’s largest city for a couple of ball games and some oysters, clams, and crab cakes—not likely.

Tuesday’s collision of the container ship Dali into Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge and the nearly immediate collapse of the span into the chilly waters below reminds us just how unforgiving and deadly maritime accidents can be. Upon termination of rescue and recovery operations, salvage and cleanup will be prioritized as the next steps in the long-term process of reopening the navigable waters to ship traffic and construction of a new bridge. Part of the effort will include monitoring for leaks of fuels and other hazardous materials from the ship, its damaged cargo containers, and vehicles and equipment that were on the bridge when it failed.

On the waters and shores of today’s Chesapeake, numerous county, state, and federal agencies, including the United States Coast Guard, monitor and inspect looking for conditions and situations that could lead to point-source or accidental discharges of petroleum products and other hazardous materials into the bay. Many are trained, equipped, and organized for emergency response to contain and mitigate spills upon detection. But this was not always the case.

Through much of the twentieth century, maritime spills of oil and other chemicals magnified the effects of routine discharges of hazardous materials and sanitary sewer effluent into the Chesapeake and its tributaries. The cumulative effect of these pollutants progressively impaired fisheries and bay ecosystems leading to noticeable declines in numbers of many aquatic species. Rather frequently, spills or discharges resulted in conspicuous fish and/or bird kills.

One of the worst spills occurred near the mouth of the Potomac River on February 2, 1976, when a barge carrying 250,000 gallons of number 6 oil sank in a storm and lost its cargo into the bay. During a month-long cleanup, the United States Coast Guard recovered approximately 167,000 gallons of the spilled oil, the remainder dispersed into the environment. A survey counted 8,469 “sea ducks” killed. Of the total number, the great majority were Horned Grebes (4,347 or 51.3%) and Long-tailed Ducks (2,959 or 34.9%). Other species included Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata) (405 or 4.8%), Common Loon (195 or 2.3%), Bufflehead (166 or 2.0%), Ruddy Duck (107 or 1.3%), Common Goldeneye (78 or 0.9%), Tundra Swan (46 or 0.5%), Greater Scaup (19 or 0.2%), American Black Duck (12 or 0.2%), Common Merganser (11 or 0.1%), Canvasback (10 or 0.1%), Double-crested Cormorant (10 or 0.1%), Canada Goose (8 or 0.1%), White-winged Scoter (Melanitta deglandi) (7 or 0.1%), Redhead (5 or 0.1%), gull species (10 or 0.1%), miscellaneous ducks and herons (13 or 0.2%) and unidentified (61 or 0.7%). During the spring migration, a majority of these birds would have made their way north and passed through the lower Susquehanna valley. The accident certainly impacted the occurrence of the listed species during that spring in 1976, and possibly for a number of years after.

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, commonly known as the Clean Water Act, put teeth into the original FWCPCA of 1948 and began reversing the accumulation of pollutants in the bay and other bodies of water around the nation. Additional amendments in 1977 and 1987 have strengthened protections and changed the culture of “dump-and-run” disposal and “dilution-is-the-solution” treatment of hazardous wastes. During the late nineteen-seventies and early nineteen-eighties, emergency response teams and agencies began organizing to control and mitigate spill events. The result has been a greater awareness and competency for handling accidental discharges of fuels and other chemicals into Chesapeake Bay and other waterways. These improvements can help minimize the environmental impact of the Dali’s collision with the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore.

SOURCES

Roland, John V., Moore, Glenn E., and Bellanca, Michael A. 1977. “The Chesapeake Bay Oil Spill—February 2, 1976: A Case History”. International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings (1977). 1977 (1): 523-527.

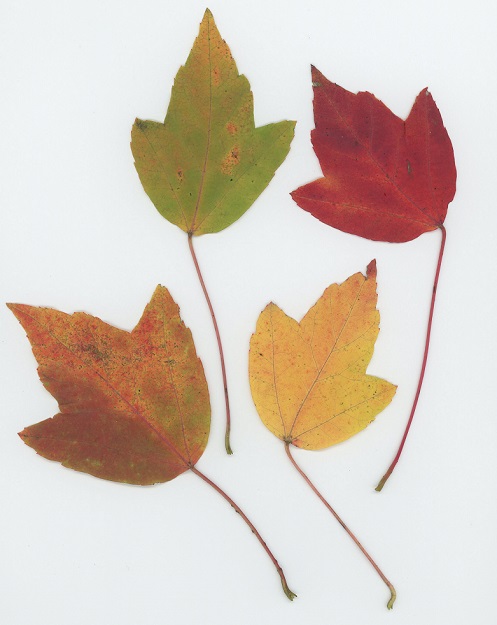

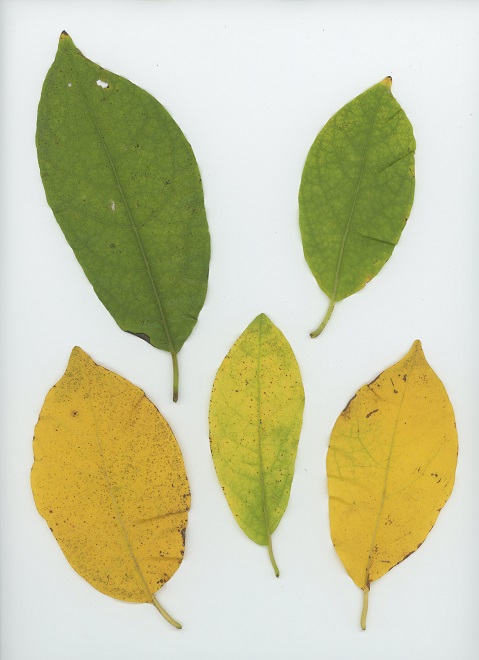

It’s that time of year. Your local county conservation district is taking orders for their annual tree sale and it’s a deal that can’t be beat. Order now for pickup in April.

The prices are a bargain and the selection includes the varieties you need to improve wildlife habitat and water quality on your property. For species descriptions and more details, visit each tree sale web page (click the sale name highlighted in blue). And don’t forget to order packs of evergreens for planting in mixed clumps and groves to provide winter shelter and summertime nesting sites for our local native birds. They’re only $12.00 for a bundle of 10.

Cumberland County Conservation District Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 22, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 18, 2024 or Friday, April 19, 2024

Dauphin County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Monday, March 18, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 18, 2024 or Friday, April 19, 2024

Lancaster County Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 8, 2024

Pickup on: Friday, April 12, 2024

Lebanon County Conservation District Tree and Plant Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 8, 2024

Pickup on: Friday, April 19, 2024

Perry County Conservation District Tree Sale—

Orders due by: Sunday, March 24, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 11, 2024

Again this year, Perry County is offering bluebird nest boxes for sale. The price?—just $12.00.

York County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 15, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 11, 2024

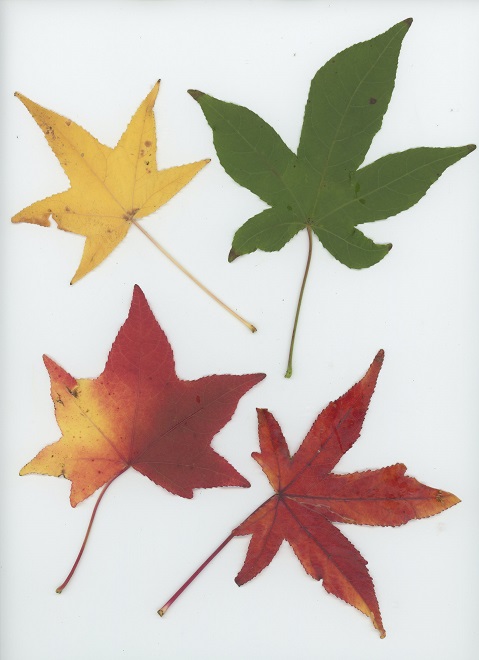

To get your deciduous trees like gums, maples, oaks, birches, and poplars off to a safe start, conservation district tree sales in Cumberland, Dauphin, Lancaster, and Perry Counties are offering protective tree shelters. Consider purchasing these plastic tubes and supporting stakes for each of your hardwoods, especially if you have hungry deer in your neighborhood.

There you have it. Be sure to check out each tree sale’s web page to find the selections you like, then get your order placed. The deadlines will be here before you know it and you wouldn’t want to miss values like these!

Heavy rains and snow melt have turned the main stem of the Susquehanna and its larger tributaries into a muddy torrent. For fish-eating (piscivorous) ducks, the poor visibility in fast-flowing turbid waters forces them to seek better places to dive for food. With man-made lakes and ponds throughout most of the region still ice-free, waterfowl are taking to these sources of open water until the rivers and streams recede and clear.

With a hard freeze on the way, the fight for life will get even more desperate in the coming weeks. Lakes will ice over and the struggle for food will intensify. Fortunately for mergansers and other piscivorous waterfowl, high water on the Susquehanna is expected to recede and clarify, allowing them to return to their traditional environs. Those with the most suitable skills and adaptations to survive until spring will have a chance to breed and pass their vigor on to a new generation of these amazing birds.

When the ground becomes snow covered, it’s hard to imagine anything lives in the vast wide-open expanses of cropland found in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s fertile valleys.

Yet, there is one group of birds that can be found scrounging a living from what little exists after a season of high-intensity farming. Meet the Horned Lark.

If you decide to take a little post-storm trip to look for Horned Larks and Lapland Longspurs, be sure to drive carefully. Do your searching on quiet rural roads with minimal traffic. Stop and park only where line-of-sight and other conditions allow it to be done safely. Use your flashers and check your mirrors often. Think before you stop and park—don’t get stuck or make a muddy mess. And most important of all, be aware that you’re on a roadway—get out of the way of traffic.

If you’re not going out to look for larks and longspurs, we do have a favor to ask of you. Please remember to slow down while you’re driving. Not only is this an accident-prone time of year for people in cars and trucks, it’s a dangerous time for birds and other wildlife too. They’re at greatest peril of getting run over while concentrated along roadsides looking for food following snow storms.

I’m worried about the beaver. Here’s why.

Imagine a network of brooks and rivulets meandering through a mosaic of shrubby, sometimes boggy, marshland, purifying water and absorbing high volumes of flow during storm events. This was a typical low-gradient stream in the valleys of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed in the days prior to the arrival of the trans-Atlantic human migrant. Then, a frenzy of trapping, tree chopping, mill building, and stream channelization accompanied the east to west waves of settlement across the region. The first casualty: the indispensable lowlands manager, the North American Beaver (Castor canadensis).

Without the widespread presence of beavers, stream ecology quickly collapsed. Pristine waterways were all at once gone, as were many of their floral and faunal inhabitants. It was a streams-to-sewers saga completed in just one generation. So, if we really want to restore our creeks and rivers, maybe we need to give the North American Beaver some space and respect. After all, we as a species have yet to build an environmentally friendly dam and have yet to fully restore a wetland to its natural state. The beaver is nature’s irreplaceable silt deposition engineer and could be called the 007 of wetland construction—doomed upon discovery, it must do its work without being noticed, but nobody does it better.

Few landowners are receptive to the arrival of North American Beavers as guests or neighbors. This is indeed unfortunate. Upon discovery, beavers, like wolves, coyotes, sharks, spiders, snakes, and so many other animals, evoke an irrational negative response from the majority of people. This too is quite unfortunate, and foolish.

North American Beavers spend their lives and construct their dams, ponds, and lodges exclusively within floodplains—lands that are going to flood. Their existence should create no conflict with the day to day business of human beings. But humans can’t resist encroachment into beaver territory. Because they lack any basic understanding of floodplain function, people look at these indispensable lowlands as something that must be eliminated in the name of progress. They’ll fill them with soil, stone, rock, asphalt, concrete, and all kinds of debris. You name it, they’ll dump it. It’s an ill-fated effort to eliminate these vital areas and the high waters that occasionally inundate them. Having the audacity to believe that the threat of flooding has been mitigated, buildings and poorly engineered roads and bridges are constructed in these “reclaimed lands”. Much of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed has now been subjected to over three hundred years-worth of these “improvements” within spaces that are and will remain—floodplains. Face it folks, they’re going to flood, no matter what we do to try to stop it. And as a matter of fact, the more junk we put into them, the more we displace flood waters into areas that otherwise would not have been impacted! It’s absolute madness.

By now we should know that floodplains are going to flood. And by now we should know that the impacts of flooding are costly where poor municipal planning and negligent civil engineering have been the norm for decades and decades. So aren’t we tired of hearing the endless squawking that goes on every time we get more than an inch of rain? Imagine the difference it would make if we backed out and turned over just one quarter or, better yet, one half of the mileage along streams in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed to North American Beavers. No more mowing, plowing, grazing, dumping, paving, spraying, or building—just leave it to the beavers. Think of the improvements they would make to floodplain function, water quality, and much-needed wildlife habitat. Could you do it? Could you overcome the typical emotional response to beavers arriving on your property and instead of issuing a death warrant, welcome them as the talented engineers they are? I’ll bet you could.

Grasshoppers are perhaps best known for the occasions throughout history when an enormous congregation of these insects—a “plague of locusts”—would assemble and rove a region to feed. These swarms, which sometimes covered tens of thousands of square miles or more, often decimated crops, darkened the sky, and, on occasion, resulted in catastrophic famine among human settlements in various parts of the world.

The largest “plague of locusts” in the United States occurred during the mid-1870s in the Great Plains. The Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus), a grasshopper of prairies in the American west, had a range that extended east into New England, possibly settling there on lands cleared for farming. Rocky Mountain Locusts, aside from their native habitat on grasslands, apparently thrived on fields planted with warm-season crops. Like most grasshoppers, they fed and developed most vigorously during periods of dry, hot weather. With plenty of vegetative matter to consume during periods of scorching temperatures, the stage was set for populations of these insects to explode in agricultural areas, then take wing in search of more forage. Plagues struck parts of northern New England as early as the mid-1700s and were numerous in various states in the Great Plains through the middle of the 1800s. The big ones hit between 1873 and 1877 when swarms numbering as many as trillions of grasshoppers did $200 million in crop damage and caused a famine so severe that many farmers abandoned the westward migration. To prevent recurrent outbreaks of locust plagues and famine, experts suggested planting more cool-season grains like winter wheat, a crop which could mature and be harvested before the grasshoppers had a chance to cause any significant damage. In the years that followed, and as prairies gave way to the expansive agricultural lands that presently cover most of the Rocky Mountain Locust’s former range, the grasshopper began to disappear. By the early years of the twentieth century, the species was extinct. No one was quite certain why, and the precise cause is still a topic of debate to this day. Conversion of nearly all of its native habitat to cropland and grazing acreage seems to be the most likely culprit.

In the Mid-Atlantic States, the mosaic of the landscape—farmland interspersed with a mix of forest and disturbed urban/suburban lots—prevents grasshoppers from reaching the densities from which swarms arise. In the years since the implementation of “Green Revolution” farming practices, numbers of grasshoppers in our region have declined. Systemic insecticides including neonicotinoids keep grasshoppers and other insects from munching on warm-season crops like corn and soybeans. And herbicides including 2,4-D (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) have, in effect, become the equivalent of insecticides, eliminating broadleaf food plants from the pasturelands and hayfields where grasshoppers once fed and reproduced in abundance. As a result, few of the approximately three dozen species of grasshoppers with ranges that include the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are common here. Those that still thrive are largely adapted to roadsides, waste ground, and small clearings where native and some non-native plants make up their diet.

Here’s a look at four species of grasshoppers you’re likely to find in disturbed habitats throughout our region. Each remains common in relatively pesticide-free spaces with stands of dense grasses and broadleaf plants nearby.

CAROLINA GRASSHOPPER

Dissosteira carolina

DIFFERENTIAL GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus differentialis

TWO-STRIPED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus bivittatus

RED-LEGGED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus femurrubrum

Protein-rich grasshoppers are an important late-summer, early-fall food source for birds. The absence of these insects has forced many species of breeding birds to abandon farmland or, in some cases, disappear altogether.

To pass the afternoon, we sat quietly along the edge of a pond created recently by North American Beavers (Castor canadensis). They first constructed their dam on this small stream about five years ago. Since then, a flourishing wetland has become established. Have a look.

Isn’t that amazing? North American Beavers build and maintain what human engineers struggle to master—dams and ponds that reduce pollution, allow fish passage, and support self-sustaining ecosystems. Want to clean up the streams and floodplains of your local watershed? Let the beavers do the job!

Your best bet for finding migrating shorebirds in the lower Susquehanna region is certainly a visit to a sandbar or mudflat in the river. The Conejohela Flats off Washington Boro just south of Columbia is a renowned location. Some man-made lakes including the one at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area are purposely drawn down during the weeks of fall migration to provide exposed mud and silt for feeding and resting sandpipers and plovers. But with the Susquehanna running high due to recent rains and the cost of fuel trending high as well, maybe you want to stay closer to home to do your observing.

Fortunately for us, migratory shorebirds will drop in on almost any biologically active pool of shallow water and mud that they happen to find. This includes flooded portions of fields, construction sites, and especially stormwater retention basins. We stopped by a new basin just west of Hershey, Pennsylvania, and found more than two dozen shorebirds feeding and loafing there. We took each of these photographs from the sidewalk paralleling the south shore of the pool, thus never flushing or disturbing a single bird.

So don’t just drive by those big puddles, stop and have a look. You never know what you might find.

Those mid-summer post-breeding wanders continue to delight birders throughout the Mid-Atlantic States. One colorful denizen of ponds and wetlands that has yet to put in an appearance in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed this year is the Black-bellied Whistling Duck. You might remember this species from earlier posts describing the fortieth anniversary of your editor’s journey to the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Like many other birds, the Black-bellied Whistling Duck has been extending its range north from Texas, Florida, and other states along the Gulf Coastal Plain. Populations of these waterfowl are chiefly resident birds with some short-distance movement to find suitable habitat for feeding and nesting. They are not usually migratory, so summertime wandering may be the mechanism for their discovery of new habitats advantageous for nesting in areas north of their current home.

Presently, at least two dozen Black-bellied Whistling Ducks are being seen regularly at a stormwater retention pond in a housing subdivision along Amalfi Drive west of Smyrna, Delaware. This small population of avian tourists has spent at least two summers in the area. Just yesterday, Black-bellied Whistling Ducks were seen and photographed about ten miles to the east at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Nine were counted there while 27 were being watched simultaneously at the Amalfi site. Earlier this week, a single Black-bellied Whistling Duck visited the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge in Philadelphia, indicating that the influx of these vagrants has transited the entire Delmarva Peninsula and entered Pennsylvania. So while you’re out watching for those first southbound migrants of the year, be on the lookout for wayward wanderers too—wanderers like Black-bellied Whistling Ducks!

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

The gasoline and gunpowder gang’s biggest holiday of the year has arrived yet again. Where does all the time go?

In observance of this festive occasion, we’ve decided to take a look at all the stuff that’s floating around in the atmosphere before all the motor travel, celebratory fires, and exciting explosions get underway.

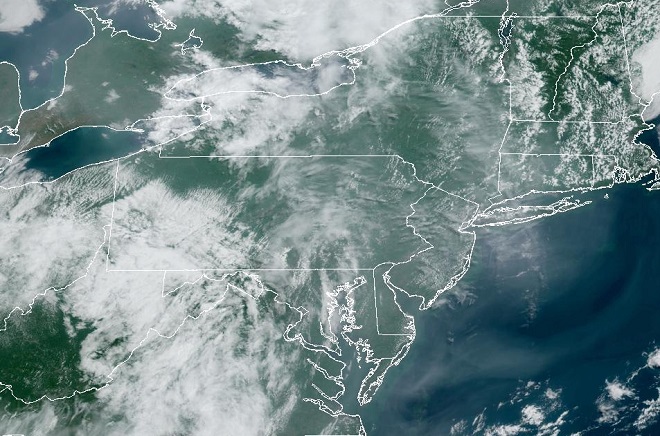

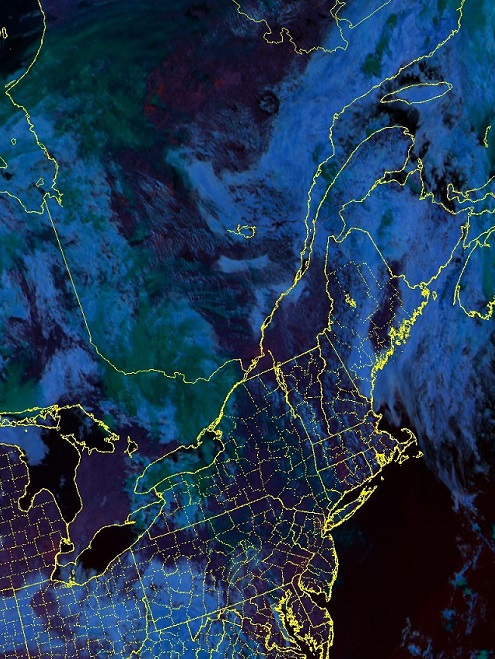

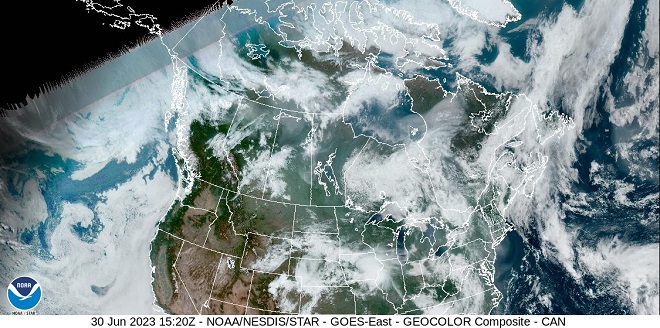

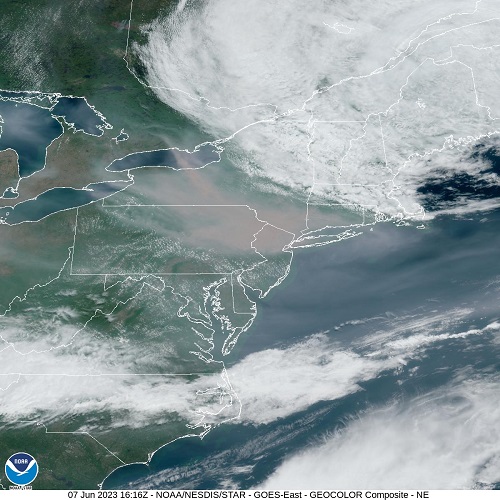

We’ll start with the smoke from wildfires in Canada…

If you think that smoke accounts for all the particulate matter now obscuring skies in the northern half of the western hemisphere, then have a gander at this…

As you can see, natural processes are currently providing a plentiful load of particulates in our skies. There’s no real need to aggravate yourself and the situation by sitting in traffic or burning your groceries on the barbecue. And you can let those cult-like homeowner chores for later. After all, running the mower, whacker, and blower will only add to the airborne pollutants. While celebrating this Fourth of July, why risk mangling fingers on your throwing hand or catching the neighbor’s house on fire when you could just relax and quietly eat ice cream or watermelon? Yeah, that’s more like it.

Here’s a look at some native plants you can grow in your garden to really help wildlife in late spring and early summer.

Watch the cloud on the move—click here for a GIF animation of this image.

Are you worried about your well running dry this summer? Are you wondering if your public water supply is going to implement use restrictions in coming months? If we do suddenly enter a wet spell again, are you concerned about losing valuable rainfall to flooding? A sensible person should be curious about these issues, but here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, we tend to take for granted the water we use on a daily basis.

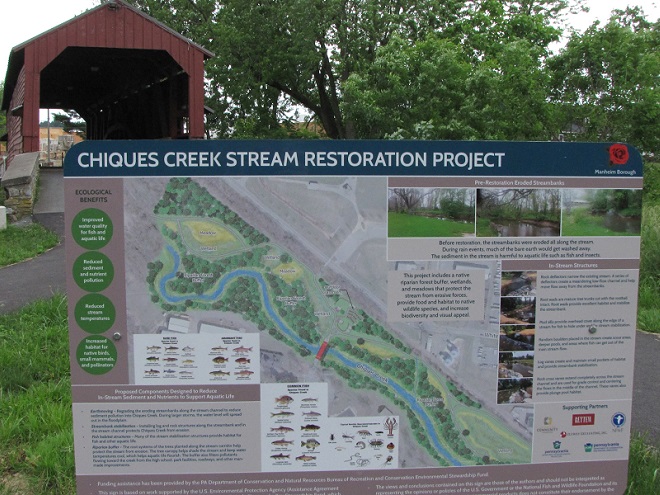

This Wednesday, June 7, you can learn more about the numerous measures we can take, both individually and as a community, to recharge our aquifers while at the same time improving water quality and wildlife habitat in and around our streams and rivers. From 5:30 to 8:00 P.M., the Chiques Creek Watershed Alliance will be hosting its annual Watershed Expo at the Manheim Farm Show grounds adjacent to the Manheim Central High School in Lancaster County. According to the organization’s web page, more than twenty organizations will be there with displays featuring conservation, aquatic wildlife, stream restoration, Honey Bees, and much more. There will be games and custom-made fish-print t-shirts for the youngsters, plus music to relax by for those a little older. Look for rain barrel painting and a rain barrel giveaway. And you’ll like this—admission and ice cream are free. Vendors including food trucks will be onsite preparing fare for sale.

And there’s much more.

To help recharge groundwater supplies, you can learn how to infiltrate stormwater from your downspouts, parking area, or driveway…

…there will be a tour of a comprehensive stream and floodplain rehabilitation project in Manheim Memorial Park adjacent to the fair grounds…

…and a highlight of the evening will be using an electrofishing apparatus to collect a sample of the fish now populating the rehabilitated segment of stream…

…so don’t miss it. We can hardly wait to see you there!

The 2023 Watershed Expo is part of Lancaster Conservancy Water Week.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY SEVEN—May 27, 1983

“Bentsen State Park”

“6 A.M. alarm rang. After breakfast we walked an hour or more. At 8:15 we phoned Father Tom for more information. We next went back to Anzalduas County Park in hopes of seeing a Hook-billed Kite. It is now 11:30 and NO luck. Steve got his first lifer — Red-billed Pigeon. We parked on a dirt dike and they went walking. I took a nap.”

Based on new tips from Father Tom, we had back-tracked east along the Rio Grande to look for Hook-billed Kite, Red-billed Pigeon (Patagioenas flavirostris), and other species before continuing west toward Falcon Dam in coming days. The pigeon was yet another specialty with a range that extends north from Central America into the subtropical riparian forests of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

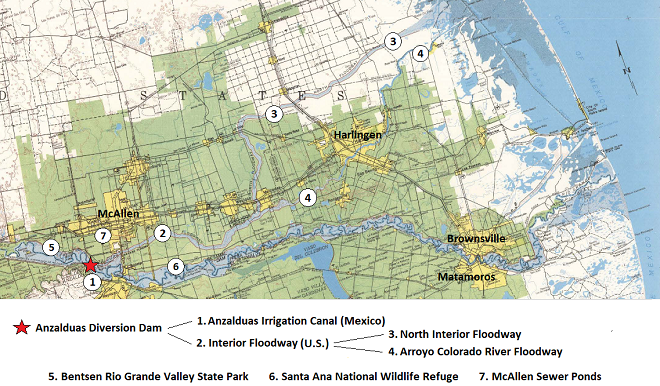

Anzalduas County Park is located along the Rio Grande at the Anzalduas Diversion Dam, part of a network of flood control projects initiated in the 1930s to reign in the “untamed river”. Construction on this particular dam began in 1956 and was completed in 1960. Operation of diversion and flood control dams on the Rio Grande has functionally eliminated stream meander along its present course, thus the delta that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley will cease to experience the morphological changes that create wetlands, resacas, and other natural features in the floodplain. Thought to be excellent ideas at the time, most of these projects were based on a blurred vision of the connection between streams, their floodplains, and the watershed’s aquifer. This condition has manifested itself as a blindness to the finite nature of water supplies, particular where consumption rates are still sharply rising while groundwater recharge is diminishing.

In addition to the Red-billed Pigeon, we found Brown-headed Cowbirds at Anzalduas County Park. Flying over the adjacent reservoir/river there were Caspian Terns. We identified some turtles too—Red-eared Sliders.

“After my nap, I took pictures of the place and of the men coming back. Then to the McAllen Sewage Ponds where we had some luck — Eared Grebe and others.”

The McAllen Sewage Ponds were like a little oasis for waterbirds. Though not a specialty of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the Eared Grebe (Podiceps nigricollis) was a western species we were happy to have seen. A Gulf Coast species, Mottled Duck (Anas fulvigula), was another welcome find. Other sightings included Least Grebe, 100 Ruddy Ducks, Northern Shoveler, Mallard, Black-bellied Whistling Duck, American Coot, Common Gallinule, Spotted Sandpiper, White-faced Ibis (Plegadis chihi), Black-necked Stilt, Franklin’s Gull, Least Tern (Sternula antillarum), Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Great-tailed Grackle, and Bronzed Cowbird.

Swimming around in the McAllen Sewage Ponds was a Nutria (Myocastor coypus), also known as the Coypu, a mammal resembling a giant muskrat—remember, things really are bigger in Texas.

“Next to the Time Out Camp Ground to check with a couple I met in February. They had moved, their space was empty. Back to Bentsen State Park. On the way we bought a watermelon for supper’s dessert. Rain almost all P.M. Raining now 8:00 P.M. Before supper we checked again for the Tropical Parula with no luck. The watermelon was very good for dessert.”

Details received this morning from Father Tom suggested we check the area of the Bentsen Rio Grande Valley State Park campground near a large Spanish Moss-draped tree for the nesting Tropical Parulas. I don’t recall what kind of tree it was, but the paved road circled the area surrounding it indicating that those who had designed the campground had purposely preserved this massive specimen as something unique. Despite its prominence, no sights or sounds of the Tropical Parulas were found. We reached the conclusion that we were a little late; they were gone for the year. To soothe our sorrows, we ate watermelon—very refreshing!

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY FOUR—May 24, 1983

“AOK Campground—South of Kingsville, Texas”

“Arose at 6:30 A.M. to the tune of Common Nighthawks. After breakfast, we headed for Harlingen. While driving south we saw six pairs of Black-bellied Whistling Ducks. At Harlingen we phoned Father Tom, who is an expert birder for the area.”

As we drove south to Harlingen, much our 100-mile route was through the Laureles division of the King Ranch, the largest ranch in the United States. It covers over 800,000 acres and is larger than the state of Rhode Island. The road there was as straight as an arrow with wire fences on both sides and scrubland as far as the eye could see. Things really are bigger in Texas.

Once in Harlingen, we did two things no one needs to do anymore:

Today, nearly everyone traveling such distances to find birds is carrying a cellular phone and many can use theirs to access internet sites and databases such as eBird to get current sighting information. Back in 1983, Father Tom Pincelli was a dear friend to birders visiting the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Few places had a person who was willing to answer the phone and field inquiries regarding the latest whereabouts of this or that bird. To remain current, he also had to religiously (forgive me for the pun) collect sighting information from the observers with whom he had contact. For locations elsewhere across the country, a birder in 1983 was happy just to have a phone number for a hotline with a tape-recorded message listing the unusual sightings for its covered region. If you were lucky, the volunteer logging the sightings would be able to update the tape once a week. For those who dialed his number, Father Tom provided an exceptionally personal experience.

Since 1983, Father Tom Pincelli, also known as “Father Bird”, has tirelessly promoted birding and conservation throughout the Lower Rio Grande Valley. His efforts have included hosting a P.B.S. television program and writing columns for local newspapers. He has been instrumental in developing the annual Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival. The public sentiment he has generated for the birding paradise that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley has helped facilitate the acquisition and/or protection of many key parcels of land in the region.

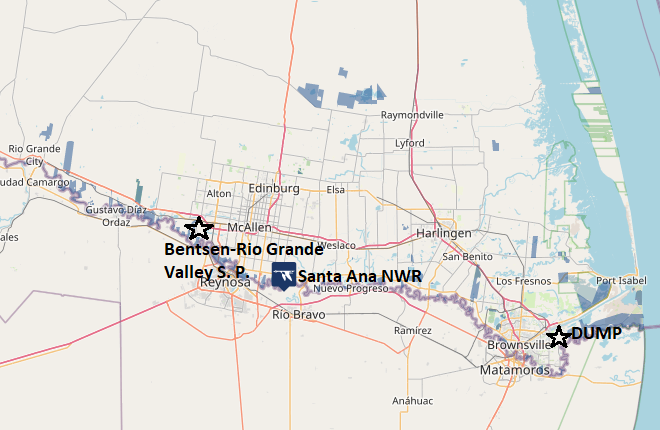

“After receiving information on locations of Tropical Parula, Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, Hook-billed Kite, Brown Jay, and Clay-colored Robin, we went on to check out the Brownsville Airport where we will meet Harold and Steve Thursday noon.”

If we were going to see these five species in the American Birding Association listing area, then we would have to see them in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. All five were target birds for each of us, including Harold who had few other possibilities for new species on the trip. Father Tom provided us with tips for finding each.

I noticed as we began moving around Harlingen and Brownsville that Russ was swiftly getting his bearings—he had been here before and was starting to remember where things were. His ability to navigate his way around allowed us to keep moving and see a lot in a short time.

In Harlingen, we easily found Mourning Doves and the non-native Rock Pigeons, species we see regularly in Pennsylvania. We became more enthusiastic about doves and pigeons soon after when we saw the first of the several other species native to south Texas, the diminutive Inca Dove (Columbina inca), also known as the Mexican Dove.

“Next, to the Brownsville Dump to see the White-necked Ravens — Then to Mrs. Benn’s in Brownsville for the Buff-bellied Hummingbird. Both lifers for Larry.”

For birders wanting to see a White-necked Raven in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the Brownsville Dump was the place to go. With very little effort—excluding a trip of nearly 2,000 miles to get there—we found them. Today, birders still go to the Brownsville Dump to find White-necked Ravens, though the dump is now called the Brownsville Landfill and the bird is known as the Chihuahuan Raven (Corvus cryptoleucus).

Mrs. Benn’s home was in a verdant residential neighborhood in Brownsville. She welcomed birders to come and see the Buff-bellied Hummingbirds that visited her feeder filled with sugar water. I don’t recall whether or not she kept a guest book for visitors to sign, but if she did, it would have included hundreds—maybe thousands—of names of people from all over North America who came to her garden to get a look at a Buff-bellied Hummingbird. After arriving, we waited a short time and sure enough, we watched a Buff-bellied Hummingbird (Amazilia yucatanensis) sipping Mrs. Benn’s home-brewed nectar from her glass feeder. This emerald hummingbird is primarily a Mexican species with a breeding range that extends north into the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. When not breeding, a few will wander north and east along the Gulf Coastal Plain as far as Florida.

Other finds at Mrs Benn’s included White-winged Dove (Zenaida asiatica), Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens), Brown-crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus tyrannulus), and Black-crested Titmouse (Baeolophus atricristatus), a species also known as Mexican Titmouse.

The Lower Rio Grande Valley from Rio Grande City east to the Gulf of Mexico is actually the river’s outflow delta. At least six historic channels have been delineated in Texas on the north side of the river’s present-day course. An equal number may exist south of the border in Mexico. Hundreds of oxbow lakes known as “resacas” mark the paths of the former channels through the delta. Many resacas are the centerpieces of parks, wildlife refuges, and housing developments. Still others are barely detectable after being buried in silt deposits left by the meandering river. Channelization, land disturbances related to agriculture, and a boom in urbanization throughout the valley have disconnected many of the most recently formed resacas from the river’s floodplain, preventing them from absorbing the impact of high-water events. These alterations to natural morphology can severely aggravate flooding and water pollution problems.

“On to Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. We walked to Pintail Lake and saw 6 Black-bellied Whistling Ducks and 2 Mississippi Kites and 1 Pied-billed Grebe. We drove the route thru the park with great results—Anhingas, Least Grebe, and more Black-bellied Whistling Ducks.

Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge on the Rio Grande is not only a birder’s mecca, 300 species of butterflies have been identified there. That’s half the species known to occur in the United States! Its subtropical riparian forest and resaca lakes provide habitat for hundreds of migratory and resident bird species including many Central and South American species that reach the northern limit of their range in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Two endangered cats occur in the park—the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and the Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi).

We saw no cats at Santa Ana, but did quite well with the birds. Our list included the species listed above plus Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis); Louisiana Heron, now known as Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor); Plain Chachalacas; Purple Gallinule; Common Gallinule (Gallinula galeata); American Coot; Killdeer; Greater Yellowlegs; the coastal Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla); and its close relative of the central flyway and continental interior, the Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan). Others finds were White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, Inca Dove, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Ladder-backed Woodpecker (Dryobates scalaris), Brown-crested Flycatcher, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and House Sparrow. A real standout was the colorful Green Jay (Cyanocorax luxosus), yet another tropical Central American species found north only as far as the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

“We were unlucky not to find a campground at McAllen, so we went on to Bentsen State Park where we got a camp spot. After a sauerkraut supper, we birded till dark, then showered and wrote up the log. Very hot today.”

Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, like the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, is located along the Rio Grande river and features dense subtropical riparian forest that grows in the naturally-deposited silt levees of the floodplain surrounding several lake-like oxbow resacas. Montezuma Bald Cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) is a native specialty found there but nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley. During our visit, we marveled at the epiphyte Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) adorning many of the more massive trees in the park. Willows lined much of the river shoreline.

Over time, flood control projects such as man-made dams, drainage ditches, and levees have impaired stormwater capture and aquifer recharge in the floodplain. These alterations to watershed hydrology have resulted in drier soils in many sections of the Lower Rio Grande Valley’s riparian forests. Where drier conditions persist, xeric (dry soil) scrubland plants are slowly overtaking the moisture-dependent species. As a result, the park’s woodlands are composed of trees with a variety of microclimatic requirements—Anaqua (Ehretia anacua), Cedar Elm (Ulmus crassifolia), Texas Ebony (Ebenopsis ebano), hackberry, mesquite, Mexican Ash (Fraxinus berlandieriana), retama, and tepeguaje are the principle species. The park’s subtropical Texas Wild Olive (Cordia boissieri) grows in the wild nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

While a majority of birders visiting Benten-Rio Grande State Park come to see the more tropical specialties of the riparian woods, searching the brushy habitat of the park’s scrubland can afford one the opportunity to see species typical of the southwestern United States and deserts of Mexico. This scrubland of the Lower Rio Grande Valley is part of the Tamaulipan Mezquital ecoregion, an area of xeric (dry soil) shrublands and deserts that extends northwest from the delta through most of south Texas and into the bordering provinces of northeastern Mexico.

Our campsite was located in prime birding habitat. We were a short walk away from one of the park’s flooded oxbow resacas and vegetation was thick along the roadsides. It was no surprise that the place abounded with birds. An evening stroll yielded Plain Chachalaca, White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, White-fronted Dove, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Brown-crested Flycatcher, Green Jay, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and Bronzed Cowbird (Molothrus aeneus). At nightfall, we listened to the calls of an Eastern Screech Owl (Megascops asio), Common Nighthawks, and Common Pauraque (Nyctidromus albicollis), a nightjar of Central and South America that nests only as far north as the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The Common Pauraque is the tropical counterpart of the Eastern Whip-poor-will, a Neotropical migrant that nests in scattered forest locations throughout eastern North America.

I would note that we saw no “snowbirds”—long-term vacationers from the northern states and Canada who fill the park through the cooler months of fall, winter, and spring. They were gone for the summer. But for a few other friendly folks, we had the entire campground to ourselves for the duration of our stay.

During the spare time you have on a rainy day like today, you may have asked yourself, “Just how much water do people collect with those rain barrels they have attached to their downspouts?” That’s a good question. Let’s do a little math to figure it out.

First, we need to determine the area of the roof in square feet. There’s no need to climb up there and measure angles, etc. After all, we’re not ordering shingles—we’re trying to figure out the surface area upon which rain will fall vertically and be collected. For our estimate, knowing the footprint of the building under roof will suffice. We’ll use a very common footprint as an example—1,200 square feet.

By dividing the area of the roof by 12, we can calculate the volume of water in cubic feet that is drained by the spouting for each inch of rainfall…

Next, we multiply the volume of water in cubic feet by 7.48 to convert it to gallons per inch of rainfall…

That’s a lot of water. Just one inch of rain could easily fill more than a single rain barrel on a downspout. Many homemade rain barrels are fabricated using recycled 55-gallon drums. Commercially manufactured ones are usually smaller. Therefore, we can safely say that in the case of a building with a footprint of 1,200 square feet, an array of at least 14 rain barrels is required to collect and save just one inch of rainfall. Wow!

Why send that roof water down the street, down the drain, down the creek, or into the neighbors property? Wouldn’t it be better to catch it for use around the garden? At the very least, shouldn’t we be infiltrating all the water we can into the ground to recharge the aquifer? Why contribute to flooding when you and I are gonna need that water some day? Remember, the ocean doesn’t need the excess runoff—it’s already full.

As your editor here at susquehannawildlife.net, I’d like to take a moment to thank all the volunteers who gave of their valuable time today to pick up litter, plant trees, and take other civic actions in observance of Earth Day. Your hard work has not gone unnoticed.

Special appreciation goes out to the anonymous crew that worked its way through the area surrounding our headquarters to pick up the trash on the rental and business properties in the neighborhood. My personal thanks is extended to you.

If you’ve never lived in an urban or downtown area, you’re probably unaware of the environmental damage and decline in the quality of life that occurs when “investors” start buying up the houses near you. The first things to go are the trees and shrubs—less maintenance that way. Next, more paving is installed to park more cars. That leads to more stormwater runoff, so look out if you happen to live downstream. Then the long-term neglect begins. The absentee “slumlords” show up only to collect the rent, if at all. Unless the tenants are conscientious enough to do a little sweeping, the rubbish begins to accumulate. It’s a funny thing, when there’s a bunch of junk lying around, people feel compelled to start dumping more. So to you volunteers who today helped nip the problem in the bud with your efforts, I want you to know that you’re the best! As for you greedy landlords—shame on you.

Have you noticed a purple haze across the fields right now? If so, you may have wondered, “What kind of flowers are they?”

Say hello to Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum), a non-native invasive species that has increased its prevalence in recent years by finding an improved niche in no-till cropland. Purple Dead Nettle, also known as Red Dead Nettle, is native to Asia and Europe. It has been a familiar early spring “weed” in gardens, along roadsides, and in other disturbed ground for decades.

Purple Dead Nettle owes its new-found success to the timing of its compressed growing season. Its tiny seeds germinate during the fall and winter, after crops have been harvested and herbicide application has ended for the season. The plants flower early in the spring and are thus particularly attractive to Honey Bees and other pollinators looking for a source of energy-rich nectar as they ramp up activity after winter lock down. In many cases, Purple Dead Nettle has already completed its flowering cycle and produced seeds before there is any activity in the field to prepare for planting the summer crop. The seeds spend the warmer months in dormancy, avoiding the hazards of modern cultivation that expel most other species of native and non-native plants from the agricultural landscape.

While modern farming has eliminated a majority of native plant and animal species from agricultural lands of the lower Susquehanna valley, its crop management practices have simultaneously invited vigorous invasion by a select few non-native species. High-intensity farming devotes its acreage to providing food for a growing population of people—not to providing wildlife habitat. That’s why it’s so important to minimize our impact on non-farm lands throughout the remainder of the watershed. If we continue subdividing, paving, and mowing more and more space, we’ll eventually be living in a polluted semi-arid landscape populated by little else but non-native invasive plants and animals. We can certainly do better than that.

This linear grove of mature trees, many of them nearly one hundred years old, is a planting of native White Oaks (Quercus alba) and Swamp White Oaks (Quercus bicolor).

Imagine the benefit of trees like this along that section of stream you’re mowing or grazing right now. The Swamp White Oak in particular thrives in wet soils and is available now for just a couple of bucks per tree from several of the lower Susquehanna’s County Conservation District Tree Sales. These and other trees and shrubs planted along creeks and rivers to create a riparian buffer help reduce sediment and nutrient pollution. In addition, these vegetated borders protect against soil erosion, they provide shade to otherwise sun-scorched waters, and they provide essential wildlife habitat. What’s not to love?

The following native species make great companions for Swamp White Oaks in a lowland setting and are available at bargain prices from one or more of the County Conservation District Tree Sales now underway…

So don’t mow, do something positive and plant a buffer!

Act now to order your plants because deadlines are approaching fast. For links to the County Conservation District Tree Sales in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, see our February 18th post.

County Conservation District Tree Sales are underway throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Now is the time to order for pickup in April. The prices are a bargain and the selection is fabulous. For species descriptions and more details, visit each tree sale web page (click the sale name highlighted in blue). And don’t forget to order bundles of evergreens for planting in mixed clumps and groves to provide winter shelter and summertime nesting sites for our local birds. They’re only $12.00 for a bundle of 10—can’t beat that deal!

Cumberland County Conservation District Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 24, 2023

Pickup on: Thursday, April 20, 2023 or Friday, April 21, 2023

Dauphin County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Monday, March 20, 2023

Pickup on: Thursday, April 20, 2023 or Friday, April 21, 2023

Lancaster County Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 10, 2023

Pickup on: Thursday, April 13, 2023

Lebanon County Conservation District Tree and Plant Sale—

Orders due by: Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Pickup on: Friday, April 7, 2023

Perry County Conservation District Tree Sale—(click on 2023 Tree Sale Brochure tab when it scrolls across the page)

Orders due by: March 22, 2023

Pickup on: Thursday, April 13, 2023

To learn more about this project and others, you’ll want to check out the Landstudies website.

At this very moment, your editor is comfortably numb and is, if everything is going according to plans, again having a snake run through the plumbing in his body’s most important muscle. It thus occurs to him how strange it is that with muscles as run down and faulty as his, people at one time asked him to come speak about and display his marvelous mussels. And some, believe it or not, actually took interest in such a thing. If the reader finds this odd, he or she would not be alone. But the peculiarities don’t stop there. The reader may find further bewilderment after being informed that the editor’s mussels are now in the collection of a regional museum where they are preserved for study by qualified persons with scientific proclivities. All of this show and tell was for just one purpose—to raise appreciation and sentiment for our mussels, so that they might be protected.

Click on the “Freshwater Mussels and Clams” tab at the top of this page to see the editor’s mussels, and many others as well. Then maybe you too will want to flex your muscles for our mussels. They really do need, and deserve, our help.

We’ll be back soon.

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection has issued a “drought watch” for much of the state’s Susquehanna basin including Dauphin, Lebanon, and Perry Counties—plus those counties to their north. Residents are asked to conserve water in the affected areas.

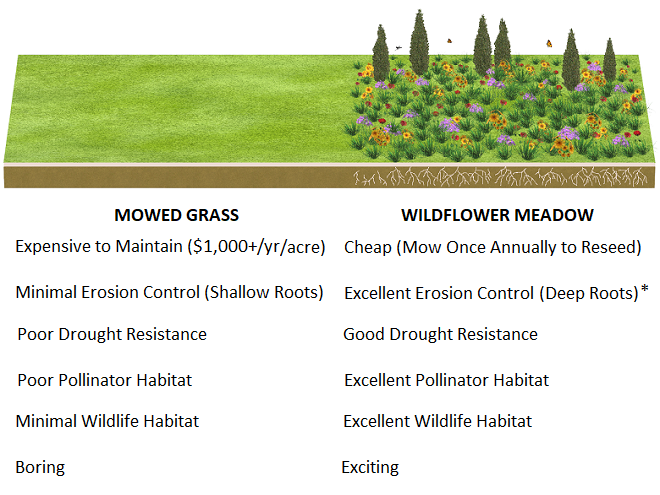

This month, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (I.U.C.N.) added the Migratory Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) to its “Red List of Threatened Species”, classifying it as endangered. Perhaps there is no better time than the present to have a look at the virtues of replacing areas of mowed and manicured grass with a wildflower garden or meadow that provides essential breeding and feeding habitat for Monarchs and hundreds of other species of animals.

If you’re not quite sure about finally breaking the ties that bind you to the cult of lawn manicuring, then compare the attributes of a parcel maintained as mowed grass with those of a space planted as a wildflower garden or meadow. In our example we’ve mixed native warm season grasses with the wildflowers and thrown in a couple of Eastern Red Cedars to create a more authentic early successional habitat.

Still not ready to take the leap. Think about this: once established, the wildflower planting can be maintained without the use of herbicides or insecticides. There’ll be no pesticide residues leaching into the soil or running off during downpours. Yes friends, it doesn’t matter whether you’re using a private well or a community system, a wildflower meadow is an asset to your water supply. Not only is it free of man-made chemicals, but it also provides stormwater retention to recharge the aquifer by holding precipitation on site and guiding it into the ground. Mowed grass on the other hand, particularly when situated on steep slopes or when the ground is frozen or dry, does little to stop or slow the sheet runoff that floods and pollutes streams during heavy rains.

What if I told you that for less than fifty bucks, you could start a wildflower garden covering 1,000 square feet of space? That’s a nice plot 25′ x 40′ or a strip 10′ wide and 100′ long along a driveway, field margin, roadside, property line, swale, or stream. All you need to do is cast seed evenly across bare soil in a sunny location and you’ll soon have a spectacular wildflower garden. Here at the susquehannawildllife.net headquarters we don’t have that much space, so we just cast the seed along the margins of the driveway and around established trees and shrubs. Look what we get for pennies a plant…

Here’s a closer look…

All this and best of all, we never need to mow.

Around the garden, we’ve used a northeast wildflower mix from American Meadows. It’s a blend of annuals and perennials that’s easy to grow. On their website, you’ll find seeds for individual species as well as mixes and instructions for planting and maintaining your wildflower garden. They even have a mix specifically formulated for hummingbirds and butterflies.

Nothing does more to promote the spread and abundance of non-native plants, including invasive species, than repetitive mowing. One of the big advantages of planting a wildflower garden or meadow is the opportunity to promote the growth of a community of diverse native plants on your property. A single mowing is done only during the dormant season to reseed annuals and to maintain the meadow in an early successional stage—preventing reversion to forest.

For wildflower mixes containing native species, including ecotypes from locations in and near the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, nobody beats Ernst Conservation Seeds of Meadville, Pennsylvania. Their selection of grass and wildflower seed mixes could keep you planting new projects for a lifetime. They craft blends for specific regions, states, physiographic provinces, habitats, soils, and uses. Check out these examples of some of the scores of mixes offered at Ernst Conservation Seeds…

We’ve used their “Showy Northeast Native Wildflower and Grass Mix” on streambank renewal projects with great success. For Monarchs, we really recommend the “Butterfly and Hummingbird Garden Mix”. It includes many of the species pictured above plus “Fort Indiantown Gap” Little Bluestem, a warm-season grass native to Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, and milkweeds (Asclepias), which are not included in their northeast native wildflower blends. More than a dozen of the flowers and grasses currently included in this mix are derived from Pennsylvania ecotypes, so you can expect them to thrive in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

In addition to the milkweeds, you’ll find these attractive plants included in Ernst Conservation Seed’s “Butterfly and Hummingbird Garden Mix”, as well as in some of their other blends.

Why not give the Monarchs and other wildlife living around you a little help? Plant a wildflower garden or meadow. It’s so easy, a child can do it.

On these hot and steamy days of summer, I get to thinking about how great it would be to have a swimming pool. Maybe I would take a little dip, you know, just to cool down. But when I really get to thinking about it, I just might do what the professor has done with his pool.

Or maybe I would do what this lady did with her pool.

Wouldn’t you?