Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

During the past week, we’ve been exploring wooded slopes around the lower Susquehanna region in search of recently arrived Neotropical birds—particularly those migrants that are singing on breeding territories and will stay to nest. Coincidentally, we noticed a good diversity of species in areas where tent caterpillar nests were apparent.

Here’s a sample of the variety of Neotropical migrants we found in areas impacted by Eastern Tent Caterpillars. All are arboreal insectivores, birds that feed among the foliage of trees and shrubs searching mostly for insects, their larvae, and their eggs.

In the locations where these photographs were taken, ground-feeding birds, including those species that would normally be common in these habitats, were absent. There were no Gray Catbirds, Carolina Wrens, American Robins or other thrushes seen or heard. One might infer that the arboreal insectivorous birds chose to establish nesting territories where they did largely due to the presence of an abundance of tent caterpillars as a potential food source for their young. That could very well be true—but consider timing.

So why do we find this admirable variety of Neotropical bird species nesting in locations with tent caterpillars? Perhaps it’s a matter of suitable topography, an appropriate variety of native trees and shrubs, and an attractive opening in the forest.

Here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the presence of Eastern Tent Caterpillar nests can often be an indicator of a woodland opening, natural or man-made, that is being reforested by Black Cherry and other plants which improve the botanical richness of the site. For numerous migratory Neotropical species seeking favorable places to nest and raise young, these regenerative areas and the forests surrounding them can be ideal habitat. For us, they can be great places to see and hear colorful birds.

As week-old snow and ice slowly disappears from the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed landscape, we ventured out to see what might be lurking in the dense clouds of fog that for more than two days now have accompanied a mid-winter warm spell.

If scenes of a January thaw begin to awaken your hopes and aspirations for all things spring, then you’ll appreciate this pair of closing photographs…

With the earth at perihelion (its closest approach to the sun) and with our home star just 27 degrees above the horizon at midday, bright low-angle light offered the perfect opportunity for doing some wildlife photography today. We visited a couple of grasslands managed by the Pennsylvania Game Commission to see what we could find…

Where should you go this weekend to see vibrantly colored foliage in our region? Where are there eye-popping displays of reds, oranges, yellows, and greens without so much brown and gray? The answer is Michaux State Forest on South Mountain in Adams, Cumberland, and Franklin Counties.

South Mountain is the northern extension of the Blue Ridge Section of the Ridge and Valley Province in Pennsylvania. Michaux State Forest includes much of the wooded land on South Mountain. Within or adjacent to its borders are located four state parks: King’s Gap Environmental Education Center, Pine Grove Furnace State Park, Caledonia State Park, and Mont Alto State Park. The vast network of trails on these state lands includes the Appalachian Trail, which remains in the mountainous Blue Ridge Section all the way to its southern terminus in Georgia.

If you want a closeup look at the many species of trees found in Michaux State Forest, and you want them to be labeled so you know what they are, a stop at the Pennsylvania State University’s Mont Alto arboretum is a must. Located next door to Mont Alto State Park along PA 233, the Arboretum at Penn State Mont Alto covers the entire campus. Planting began on Arbor Day in 1905 shortly after establishment of the Pennsylvania State Forest Academy at the site in 1903. Back then, the state’s “forests” were in the process of regeneration after nineteenth-century clear cutting. These harvests balded the landscape and left behind the combustible waste which fueled the frequent wildfires that plagued reforestation efforts for more than half a century. The academy educated future foresters on the skills needed to regrow and manage the state’s woodlands.

Online resources can help you plan your visit to the Arboretum at Penn State Mont Alto. More than 800 trees on the campus are numbered with small blue tags. The “List of arboretum trees by Tag Number” can be downloaded to tell you the species or variety of each. The interactive map provides the locations of individual trees plotted by tag number while the Grove Map displays the locations of groups of trees on the campus categorized by region of origin. A Founder’s Tree Map will help you find some of the oldest specimens in the collection and a Commemorative Tree Map will help you find dedicated trees. There is also a species list of the common and scientific tree names.

The autumn leaves will be falling fast, so make it a point this weekend to check out the show on South Mountain.

Here’s a look at some native plants you can grow in your garden to really help wildlife in late spring and early summer.

Let’s have a look at some of the magnificent native wildflowers blooming on this Mother’s Day in forests and thickets throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Aren’t they spectacular?

Why not take a stroll to have a look at these and other plants you can find growing along a nearby woodland trail? You could check out some place new and get a little exercise too!

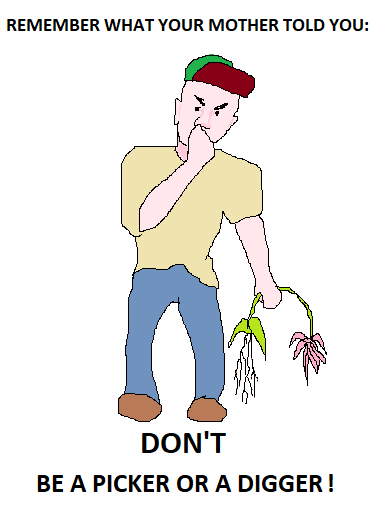

If you go, please tread lightly, take your camera, mind your manners, and…

Let’s take a quiet stroll through the forest to have a look around. The spring awakening is underway and it’s a marvelous thing to behold. You may think it a bit odd, but during this walk we’re not going to spend all of our time gazing up into the trees. Instead, we’re going to investigate the happenings at ground level—life on the forest floor.

There certainly is more to a forest than the living trees. If you’re hiking through a grove of timber getting snared in a maze of prickly Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) and seeing little else but maybe a wild ungulate or two, then you’re in a has-been forest. Logging, firewood collection, fragmentation, and other man-made disturbances inside and near forests take a collective toll on their composition, eventually turning them to mere woodlots. Go enjoy the forests of the lower Susquehanna valley while you still can. And remember to do it gently; we’re losing quality as well as quantity right now—so tread softly.

Thoughts of October in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed bring to mind scenes of brilliant fall foliage adorning wooded hillsides and stream courses, frosty mornings bringing an end to the growing season, and geese and other birds flying south for the winter.

The autumn migration of birds spans a period equaling nearly half the calendar year. Shorebirds and Neotropical perching birds begin moving through as early as late July, just as daylight hours begin decreasing during the weeks following their peak at summer solstice in late June. During the darkest days of the year, those surrounding winter solstice in late December, the last of the southbound migrants, including some hawks, eagles, waterfowl, and gulls, may still be on the move.

During October, there is a distinct change in the list of species an observer might find migrating through the lower Susquehanna valley. Reduced hours of daylight and plunges in temperatures—particularly frost and freeze events—impact the food sources available to birds. It is during October that we say goodbye to the Neotropical migrants and hello to those more hardy species that spend their winters in temperate climates like ours.

The need for food and cover is critical for the survival of wildlife during the colder months. If you are a property steward, think about providing places for wildlife in the landscape. Mow less. Plant trees, particularly evergreens. Thickets are good—plant or protect fruit-bearing vines and shrubs, and allow herbaceous native plants to flower and produce seed. And if you’re putting out provisions for songbirds, keep the feeders clean. Remember, even small yards and gardens can provide a life-saving oasis for migrating and wintering birds. With a larger parcel of land, you can do even more.

She ate only toaster pastries…that’s it…nothing else. Every now and then, on special occasions, when a big dinner was served, she’d have a small helping of mashed potatoes, no gravy, just plain, thank you. She received all her nutrition from several meals a week of macaroni and cheese assembled from processed ingredients found in a cardboard box. It contains eight essential vitamins and minerals, don’t you know? You remember her, don’t you?

Adult female butterflies must lay their eggs where the hatched larvae will promptly find the precise food needed to fuel their growth. These caterpillars are fussy eaters, with some able to feed upon only one particular species or genus of plant to grow through the five stages, the instars, of larval life. The energy for their fifth molt into a pupa, known as a chrysalis, and metamorphosis into an adult butterfly requires mass consumption of the required plant matter. Their life cycle causes most butterflies to be very habitat specific. These splendid insects may visit the urban or suburban garden as adults to feed on nectar plants, however, successful reproduction relies upon environs which include suitable, thriving, pesticide-free host plants for the caterpillars. Their survival depends upon more than the vegetation surrounding the typical lawn will provide.

The Monarch (Danaus plexippus), a butterfly familiar in North America for its conspicuous autumn migrations to forests in Mexico, uses the milkweeds (Asclepias) almost exclusively as a host plant. Here at Conewago Falls, wetlands with Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and unsprayed clearings with Common Milkweed (A. syriaca) are essential to the successful reproduction of the species. Human disturbance, including liberal use of herbicides, and invasive plant species can diminish the biomass of the Monarch’s favored nourishment, thus reducing significantly the abundance of the migratory late-season generation.

Butterflies are good indicators of the ecological health of a given environment. A diversity of butterfly species in a given area requires a wide array of mostly indigenous plants to provide food for reproduction. Let’s have a look at some of the species seen around Conewago Falls this week…

The spectacularly colorful butterflies are a real treat on a hot summer day. Their affinity for showy plants doubles the pleasure.

By the way, I’m certain by now you’ve recalled that fussy eater…and how beautiful she grew up to be.

SOURCES

Brock, Jim P., and Kaufman, Kenn. 2003. Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.