Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

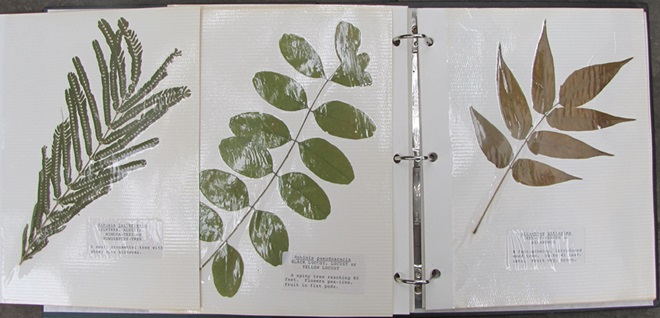

Have you noticed? Foliage throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed has been painted with the brilliant colors of autumn, so now is the time to get out there and have a look. Why not make a collection? You can pick up an inexpensive scrap book or photo album at the craft store to press and label the varieties you find. Uncle Tyler Dyer is already busy adding to the project he assembled last year. You can use his exhibit as a reference for identifying and learning a little bit more about the leaves you find.

As deciduous trees lose their foliage in coming days, it’s an excellent time to pick up and examine some samples from the species you encounter during your autumn strolls. Uncle Tyler Dyer is assembling the leaves he finds into a guide for identifying the most common wild and naturalized trees, shrubs, and woody vines of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. To use it, click on the “Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines” tab at the top of this page and check out…

…better known as Uncle Tyler’s leaf collection.

Thinking about doing some planting on your property during the fall or in the spring? Before you do, peruse the gorgeous colors offered by the native species shown on Uncle Ty’s page. You might never go back to those short-lived high maintenance cultivars of imported species ever again. And by choosing a variety of native plants, you’ll be helping wildlife too.

Oh, by the way—thanks Uncle Ty. Yes, it is far out!

Rising prices, an exhausted workforce, political polarization, and pandemic fatigue—times are tough. Product shortages have the consumer culture in a near panic. Some say the future just isn’t what it used to be.

Well, Uncle Tyler Dyer reminds us that things could be worse. He shares with us this observation, “Man, as long as people are spending money poisoning the weeds on their lawns instead of eating them, things aren’t that bad.”

Uncle Ty is particularly fond of the Common Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), “Check it out. Roasted dandelion roots can make a coffee substitute, the blossoms a wine, and the leaves used to create my favorites, nutrient-dense salads or green vegetable dishes.”

So have a homegrown salad and remember, maybe things aren’t that bad after all.

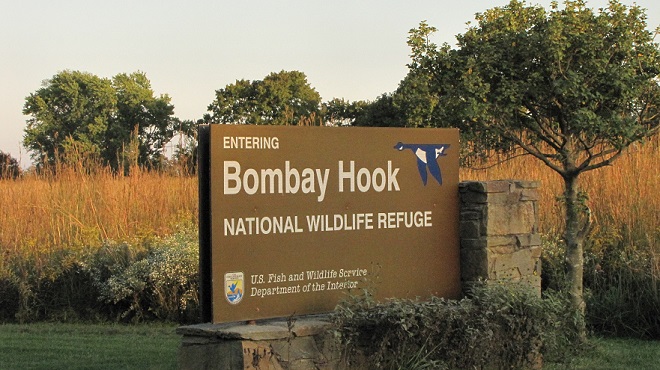

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

It’s been more than a year and a half since Uncle Tyler Dyer has been on one of our outings. He’s been laying low, keeping to himself—to protect his health. So he was quite excited when we made our way to the Delaware coast to have a look at some marine and beach life at Cape Henlopen State Park.

Uncle Ty hadn’t visited the Atlantic shoreline here for almost two decades, and he was more than a bit startled at what he saw…

A nearly sterile beach might be delightful for barefoot sunbathers and the running of the dogs, but Uncle Ty isn’t the barefoot type. He likes his sandals and a slow peaceful stroll with plenty of flora and fauna to have a look at. We could tell he was getting bored. So we headed home.

Along the way, Uncle Ty asked to stop at the Post Office. He wanted to get a stamp. Thinking he was going to fire off a terse letter of protest to the powers that be about what he saw at the beach, we obliged.

Soon, Uncle Ty trotted down the steps of the Post Office with his stamp.

Uncle Ty bought a duck stamp, so naturally we asked him when he decided to take up hunting. He explained, “Man, I gave that stuff up when I was thirteen. I’ve got the Thoreau/Walden mindset—hunting is something of an adolescent pursuit.”

It turns out Uncle Ty bought a duck stamp to support wetland acquisition and improvements, not only to benefit ducks and other wildlife living there, but to improve water quality. In Delaware, tidal estuary restoration work is underway at both the Prime Hook and Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuges on Delaware Bay. These projects will certainly enhance the salt marsh’s filtration capabilities and just might improve the populations of benthic life in the bay and adjacent ocean at Cape Henlopen.

Uncle Ty tossed the stamp atop the dashboard and we were again on our way, but we weren’t going directly home. We made a stop along the way. A stop we’ll share with you next time.

As a public service to our susquehannawildlife.net visitors, Uncle Tyler Dyer has agreed to give us a summary of the news. Uncle Ty is currently in self-imposed quarantine and will continue to remain in isolation until the threat from SARS-CoV-2 passes. Despite his age, he’s not particularly concerned about exposure to the virus or the Wuhan flu; he’s worried about getting bit by one of the “friendly” dogs that are presently dragging their owners down the sidewalks and recreation trails throughout the Susquehanna valley on a daily basis. Worse yet, he dreads the thought of winding up in the E.R. because he got bit by one of their kids. So until the subdivision dwellers go back to work and school, Uncle Ty will remain, like always, out of sight.

To get the latest scoop, be assured that Uncle Ty will poll his many exclusive sources, most of them unavailable to mainstream news reporters. He not only knows people in high places, he knows high people in places.

Here’s the news.

Hey man, I’m Ty Dyer and here’s what’s happening.

The Flat Earth Coalition of Environmental Scientists is advising the public to be alert for an impending threat posed to those who exercise “social distancing”. According to a forthcoming report, if everyone were to maintain a distance of six feet between themselves and all other individuals, those persons around the physical periphery of the mass of humanity will be dangerously close to the horizon’s end. Despite the effects of COVID-19, the world population is still growing by more than 200,000 persons each day. Soon, the earth will become overcrowded and people will begin falling off the planet, possibly within the next several weeks. A spokesperson warned that pushing, shoving, and name-calling could precede the eventual dumping of the weakest from the crowd over the side to make more space. F.E.C.E.S. would not speculate on the fate of those who take the dump; however, those living near the rim are advised to wear a face mask and a parachute while doing their business. Critics were quoted as saying, “The F.E.C.E.S. movement is full of it.”

Meanwhile, the Face Mask Manufacturers Alliance is asking those who are not sick, are not healthcare workers, or have not been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 to stop misusing their products, particularly while there is a severe supply shortage. They warn users that their masks are designed to prevent those who have been exposed to the flu virus or another contagion from transmitting it to others by capturing the aerosols produced by breathing, speaking, coughing, or sneezing. For those who have no flu symptoms or other evidence of exposure, but who insist upon wearing a mask to prevent contracting the virus despite that use being an application inverse to its design, the manufacturers ask that you please turn the mask inside out before donning. To alert others of your status, you are requested to wear your outer garments inside out as well. If you are exposed to SARS-CoV-2, test positive for the virus, or have symptoms of the flu or other contagious illness, you are instructed to wear a mask as designed, right-side out, to prevent contaminating those around you. You can also then turn your clothing right-side out as well.

There is controversy in several northeastern cities today after police officers arrested dozens of people for failing to practice safe “social distancing”. Each of those cited was quickly released to avoid crowding of the precinct houses. The controversy arose when representatives of the cities’ vice squads insisted that enforcing “social distancing” laws comes under their jurisdiction. They reminded city officials that after all, it was the vice squads who for decades have made it clear that violations of “social distancing” laws are not victimless crimes. They then accused city governments of underfunding their operations in an attempt to force them to surrender “social distancing” enforcement to patrol officers while the limited resources of the vice squads deal with the lingering jumbo soda epidemic.

Astronomers today released a statement saying that in deference to the importance of safe “social distancing”, they would eliminate using Gemini as the name of a well-known constellation until further notice. The stars comprising the Gemini twins will now be divided among two new constellations called Hank and Marty. Scientists pointed out that the stars comprising Hank and Marty are actually many light-years apart; it is our vantage point on earth that makes the two men appear to be violating the practice of safe “social distancing”. Nevertheless, they didn’t want Gemini setting a bad example.

Radio broadcasters have announced that many classic rock and pop recordings have been edited and remastered to reflect increased awareness of safe “social distancing”. Here are a few of the slightly amended hits you’ll be hearing on the airwaves soon.

The Beatles—I Want To Hold Your Hand (But My Arms Ain’t Long Enough)

The Beatles with Billy Preston—Get Back (To The Tape Mark On The Floor)

The Beatles—(This Really Isn’t A Good Time To) Come Together

The Captain & Tennille—Love Will Keep Us Together (But You Better Stand Over There)

The Carpenters —(Not So) Close To You

The Jackson 5—I’ll Be There (Or Better Yet Over Here)

Michael Jackson—Beat It (extended remix)

Bette Midler—From A Distance (Remastered)

Olivia Newton-John—(This Is No Time To Get) Physical

Pink Floyd—Comfortably Numb (You Best Skedaddle)

The Police—Don’t Stand So Close To Me (32 minute extended remix)

The Police—Every Breath You Take (You’re Suckin’ In What I Just Exhaled)

Elvis Presley—Love Me Tender (From Over There)

The Rolling Stones—Get Off Of My Cloud (And Outta My Space)

Diana Ross & The Supremes—Someday We’ll Be Together (But Not Right Now)

The Temptations—I Can’t Get Next To You (Remix)

And that’s what’s going on for April 1, 2020. Ty Dyer saying stay home, don’t get strung up in the puppet show, and remember, there are two different Amazons out there, and the only good one is a river.

At 12:07 P.M., E.D.T. today, forty-five years and eighteen days after being commissioned into commercial service on September 2, 1974, the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station’s Unit 1 reactor was shut down for the final time. There will be no refueling. There will be no more electricity furnished to the grid by the plant. It is henceforth a user, not a producer, of energy.

Here’s the final shutdown, in pictures…

It’s a hot summer weekend with a sun so bright that creosote is dripping from utility poles onto the sidewalks. Dodging these sticky little puddles of tar can cause one to reminisce about sultry days-gone-by.

Sometime in July or August each year, about half a century ago, we would cram all the gear for seven days of living into the car and head for the beaches of Delmarva or New Jersey. It was family vacation time, that one week a year when the working class fantasizes that they don’t have it so bad during the other fifty-one weeks of the year.

The trip to the coast from the Susquehanna valley was a day-long journey. Back then, four-lane highways were few beyond the cities of the northeast corridor and traffic jams stretched for miles. Cars frequently overheated and steam rolled from beneath the hoods of those stopped to cool down. There were even 55-gallon drums of non-potable water positioned at known choke points along some of the state roads so that motorists could top off their radiators and proceed on. Within these back-ups there were many Volkswagen Beetles pausing along the side of the road with the rear hood propped up. Their air-cooled engines would overheat on a hot day if the car wasn’t kept moving. But, despite the setbacks, all were motivated to continue. In time, with perseverance, the smell of saltmarsh air was soon rolling in the windows. Our destination was near.

At the shore, priority one was to spend plenty of time at the beach. Sunbathers lathered up with various concoctions of oils and moisturizers, including my personal favorite, cocoa butter, then they broiled themselves in the raging rays of the fusion-reaction furnace located just eight light-minutes away. Reflected from the white sand and ocean surf, the flaming orb’s blinding light did a thorough job of cooking all the thousands of oil-basted sun worshippers packing the tidal zone for miles and miles. You could smell the hot cocoa butter in the summer air as they burned. Well, maybe not, but you could smell something there.

By now, you’re probably saying, “Hey, why weren’t you idiots wearing protection from the sun’s harmful U.V. rays?”

Good question. Uncle Tyler Dyer reminds me that back in the sixties, a sunscreen was a shade hung to cover a window. He continued, “Man, the only sun block we had was a beach ball that happened to pass between us and the sun.”

During several of our summertime beach visits in the early 1970s, we got a different sort of oil treatment—tar balls. We never noticed the things until we got out of the water. Playing around at the tide line and taking a tumble in the surf from time to time, we must have picked them up when we rolled in the sand.

Uncle Ty wasn’t happy, “Man, they’re sticking all over our legs and feet, and look at your swim trunks, they’re ruined. And look in the sand, they’re everywhere.” The event was one of the seeds that would in time grow into Uncle Ty’s fundamental distrust of corporate culture.

Looking around, tar balls were all over everyone who happened to be near the water. Rumor on the beach was that they came from ships that passed by offshore earlier in the day. The probable source was the many oil spills that had occurred in the Mid-Atlantic region in those years. During the first six months of 1973 alone, there were over 800 oil spills there. Three hundred of those spills occurred in the waters surrounding New York City. The largest, almost half a million gallons, occurred in New York Harbor when a cargo ship collided with the tanker “Esso Brussels”. Forty percent of that spill burned in the fire that followed the mishap, the remainder entered the environment.

When it was time to clean up, we slowly removed the tar from our legs and feet by rubbing it away with a rag soaked in charcoal lighter fluid or gasoline. Needless to say, our skin turned redder than it had already been from sunburn.

After a full day in the surf, we’d be on our way back to our “home base” for summer vacation, a campground nestled somewhere in the pines on the mainland side of the tidal marshes behind our beach’s barrier island. There, we’d shake the sand out of our trunks and savor the feeling of dry clothing. As the sun set, the smoke, flicker, and crackle of dozens of campfires filled the spaces between the tents and camping trailers. Colored lights strung around awnings dazzled sun-weary eyes as night descended across the landscape. We’d commence the process of incinerating some marshmallows soon after. Then, sometime while we were roasting our weenies and warming our buns, we’d hear it.

His device didn’t have a very good muffler. It sounded like a rusty old lawn mower running on the back of a rusty old truck that didn’t sound much better. And you could see the cloud rising above the campsites around the corner as he approached. It was the mosquito man, come to rid the place of pesky nocturnal biting insects. Behind him, always, were young boys on bicycles riding in and out of the fog of insecticide that rolled from the back of the truck.

One was wise to quickly eat your campfire food and put the rest away before the fog rolled in. You had just minutes to choke down that burned up hot dog. Then the sense of urgency was gone. Everyone just sat around at picnic tables and on lawn chairs bathing in the airborne cloud. A thin layer of insecticide rubbed into the skin along with the liberal doses of Noxzema being applied to soothe sunburn pain will get you through the night just fine.

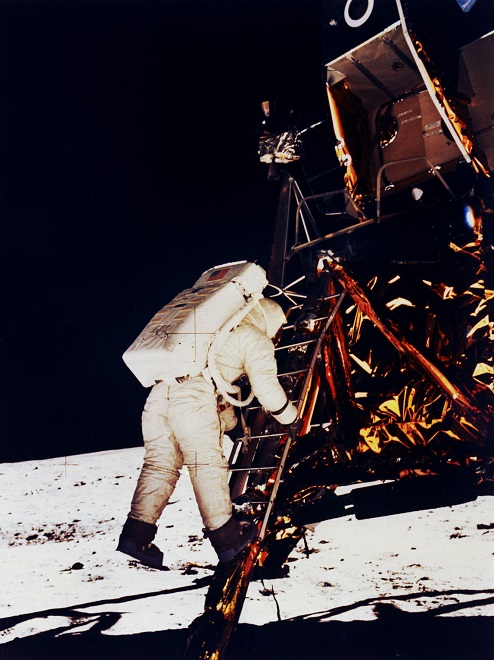

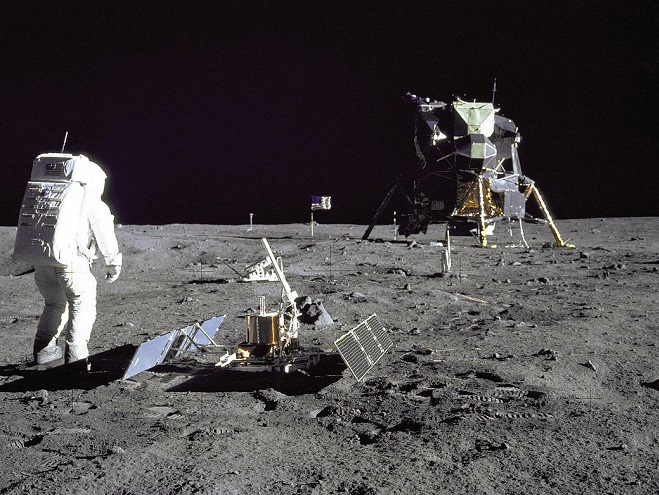

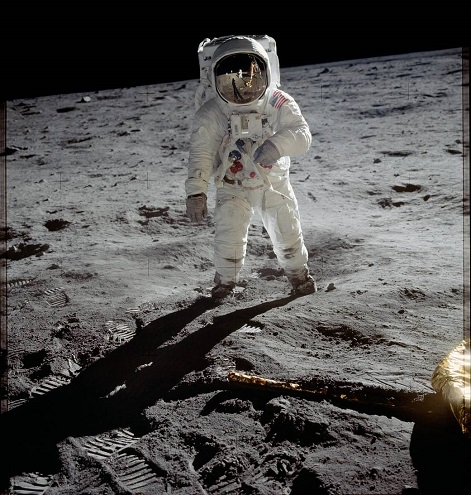

Perhaps the most memorable event to occur during our summer vacations happened at the moment of this writing, fifty years ago.

We were vacationing in a campground in southern New Jersey. Our family and the family of my dad’s co-worker gathered in a mosquito-mesh tent surrounding a small black-and-white television. An extension cord was strung to a receptacle on a nearby post, and the cathode ray tube produced the familiar picture of glowing blue tones to illuminate the otherwise dark scene. There was constant experimentation with the whip antenna to try to get a visible signal. There were no local UHF broadcasters and the closest VHF television stations were in Philadelphia, so the picture constantly had “snow” diminishing its already poor clarity. But we could see it, and I’ll never forget it.

SOURCES

Andelman, David A. “Oil Spills Here Total 300 in ’73”. The New York Times. August 8, 1973. p.41.

Cortright, Edgar M. (Editor). 1975. Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, DC.

Within the last few years, the early-summer emergence of vast waves of mayflies has caused great consternation among residents of riverside towns and motorists who cross the bridges over the lower Susquehanna. Fishermen and others who frequent the river are familiar with the phenomenon. Mayflies rise from their benthic environs where they live for a year or more as an aquatic larval stage (nymph) to take flight as a short-lived adult (imago), having just one night to complete the business of mating before perishing by the following afternoon.

In 2015, an emergence on a massive scale prompted the temporary closure of the mile-long Columbia-Wrightsville bridge while a blizzard-like flight of huge mayflies reduced visibility and caused road conditions to deteriorate to the point of causing accidents. The slimy smelly bodies of dead mayflies, probably millions of them, were removed like snow from the normally busy Lincoln Highway. Since then, to prevent attraction of the breeding insects, lights on the bridge have been shut down from about mid-June through mid-July to cover the ten to fourteen day peak of the flight period of Hexagenia bilineata, sometimes known as the Great Brown Drake, the species that swarms the bridge.

After so many years, why did the swarms of these mayflies suddenly produce the enormous concentrations seen on this particular bridge across the lower Susquehanna? Let’s have a look.

Following the 2015 flight, conservation organizations were quick to point out that the enormous numbers of mayflies were a positive thing—an indicator that the waters of the river were getting cleaner. Generally, assessments of aquatic invertebrate populations are considered to be among the more reliable gauges of stream health. But some caution is in order in this case.

Prior to the occurrence of large flights several years ago, Hexagenia bilineata was not well known among the species in the mayfly communities of the lower Susquehanna and its tributaries. The native range of the species includes the southeastern United States and the Mississippi River watershed. Along segments of the Mississippi, swarms such as occurred at Columbia-Wrightsville in 2015 are an annual event, sometimes showing up on local weather radar images. These flights have been determined to be heaviest along sections of the river with muddy bottoms—the favored habitat of the burrowing Hexagenia bilineata nymph. This preferred substrate can be found widely in the Susquehanna due to siltation, particularly behind dams, and is the exclusive bottom habitat in Lake Clarke just downstream of the Columbia-Wrightsville bridge.

Native mayflies in the Susquehanna and its tributaries generally favor clean water in cobble-bottomed streams. Hexagenia bilineata, on the other hand, appears to have colonized the river (presumably by air) and has found a niche in segments with accumulated silt, the benthic habitats too impaired to support the native taxa formerly found there. Large flights of burrowing mayflies do indicate that the substrate didn’t become severely polluted or eutrophic during the preceding year. And big flights tell us that the Susquehanna ecosystem is, at least in areas with silt bottoms, favorable for colonization by the Great Brown Drake. But large flights of Hexagenia bilineata mayflies don’t necessarily give us an indication of how well the Susquehanna ecosystem is supporting indigenous mayflies and other species of native aquatic life. Only sustained recoveries by populations of the actual native species can tell us that. So, it’s probably prudent to hold off on the celebrations. We’re a long way from cleaning up this river.

In the absence of man-made lighting, male Great Brown Drakes congregate over waterways lit often by moonlight alone. The males hover in position within a swarm, often downwind of an object in the water. As females begin flight and pass through the swarm, they are pursued by the males in the vicinity. The male response is apparently sight motivated—anything moving through their field of view in a straight line will trigger a pursuit. That’s why they’re so pesky, landing on your face whenever you approach them. Mating takes place as males rendezvous with airborne females. The female then drops to the water surface to deposit eggs and later die—if not eaten by a fish first. Males return to the swarm and may mate again and again. They die by the following afternoon. After hatching, the larvae (nymphs) burrow in the silt where they’ll grow for the coming year. Feathery gills allow them to absorb oxygen from water passing through the U-shaped refuge they’ve excavated.

Several factors increase the likelihood of large swarms of Great Brown Drakes at bridges. Location is, of course, a primary factor. Bridges spanning suitable habitat will, as a minimum, experience incidental occurrences of the flying forms of the mayflies that live in the waters below. Any extraordinarily large emergence will certainly envelop the bridge in mayflies. Lights, both fixed and those on motor vehicles, enhance the appearance of movement on a bridge deck, thus attracting hovering swarms of male Hexagenia bilineata and other species from a greater distance, leading to larger concentrations. Concrete walls along the road atop the bridge lure the males to try to hover in a position of refuge behind them, despite the vehicles that disturb the still air each time they pass. The walls also function as the ultimate visual attraction as headlamp beams and shadows cast by moving vehicles are projected onto them over the length of the bridge. Vast numbers of dead, dying, and maimed mayflies tend to accumulate along these walls for this reason.

The absence of illumination from fixed lighting on the deck of the bridge reduces the density of Great Brown Drake swarms. Some communities take mayfly countermeasures one step further. Along the Mississippi, some bridges are fitted with lights on the underside of the deck to attract the mayflies to the area directly over the water, concentrating the breeding mayflies and fishermen alike. The illumination below the bridge is intended to draw mayflies away from light created by headlamps on motor vehicles passing by on the otherwise dark deck above. Lights beneath the bridge also help prevent large numbers of mayflies from being drawn away from the water toward lights around businesses and homes in neighborhoods along the shoreline—where they can become a nuisance.

SOURCES

Edsall, Thomas A. 2001. “Burrowing Mayflies (Hexagenia) as Indicators of Ecosystem Health.” Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management. 43:283-292.

Fremling, Calvin R. 1960. Biology of a Large Mayfly, Hexagenia bilineata (Say), of the Upper Mississippi River. Research Bulletin 482. Agricultural and Home Economics Experiment Station, Iowa State University. Ames, Iowa.

McCafferty, W. P. 1994. “Distributional and Classificatory Supplement to the Burrowing Mayflies (Ephemeroptera: Ephimeroidea) of the United States.” Entomological News. 105:1-13.

It had been quite a few years, decades actually, since Uncle Tyler Dyer and I had visited the State Museum of Pennsylvania, formerly the William Penn Museum, in Harrisburg. Several days ago we decided to stop by to see what’s new.

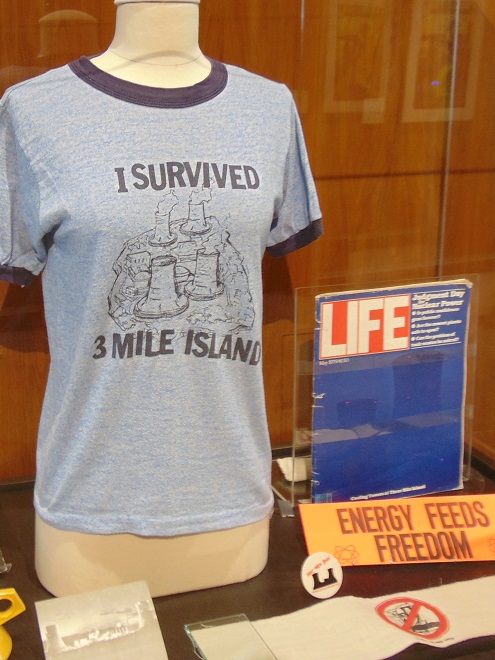

I was fussing around with the official “Life in the Lower Susquehanna Watershed” camera while walking slowly down an entrance corridor when I heard Uncle Ty exclaim from up ahead, “Hey man, that’s my T-shirt!”

There it was, neatly screen-printed on luxurious , but functional, blended cotton and polyester, just like the one Uncle Ty wore forty years ago. This priceless gem was no iron-on job. It was the real thing, just like Coke, but a little bit more expensive.

Uncle Ty said that, other than his own artistic creations, his T.M.I. T-shirt was the only one he wore during the summer of ’79. It even had spots of hardened wax in the fabric around the belly section where his candle had dripped during one of the anti-nuclear energy protest vigils he attended.

I wasn’t so certain, I thought he had a few others in his rotation back then. All those corporate beer brand and pop music group T-shirts were really popular. And “Grease”, Uncle Ty really liked Olivia Newton-John back then. He had a “Grease” T-shirt for sure. Then I remembered, and I reminded him, “You were wearing a Buck Tractor Pulls T-shirt back then, weren’t you?” I was sure of it, nice artwork of a hopped-up farm tractor on the front and “See You at the Buck” across the back.

“No way man,” he retorted, “There’s no way I went down there to waste a Saturday night with that gasoline and gunpowder gang. I would have sooner spent a Saturday night getting a tooth worked on by an angry intoxicated dentist!”

Oh well, everybody has there own idea of a good time.

We’re beginning to worry about Uncle Tyler Dyer. It’s been almost a month since a tornado descended from an eastbound cloud that first passed by Three Mile Island, and from him we’ve heard not a word about it. And the rainfall totals during the past year, well above normal and record setting, but not a peep from him about it. The floods too, and the gusty thunderstorms that either seemed to strike only our town, or would instead let us high and dry while passing off to the north or south. For forty years, from Uncle Ty’s point of view, these phenomena were all attributable to those towers down at Three Mile Island. He would say, “Man, you know the lightning in that thunderstorm was terrible because of T.M.I. You know that, don’t you?”

If you happen to live in the lower Susquehanna valley, you’ve probably heard comments like that at the local diner, taproom, or gathering of family and friends. Many are offered by good-humored folk, in jest, to enliven the conversation. It makes a chat about the weather a bit more exciting. Then to, there are those who became extraordinarily suspicious of the nuclear facility at Three Mile Island after the accident. To them, any deviation from the status quo must be caused by those big towers down there. Even if they don’t fully believe what they’re saying, it matters that they don’t miss the chance to get in a jab, even if it’s a glancing one. That’s Uncle Ty. He sees that plant in a different light than we do, from a different perspective. To him, Three Mile Island is the ultimate symbol of corporate evil. It’s not about the fuel used to operate the reactor. The invisible threat of radioactivity is a metaphor for the secretive operations of sinister big business. Those towers are a collection of monoliths representing greed, interlocking corporate directorships, and immunity from accountability. And no one is going to change his mind.

If you remember reading, watching, or listening to news reports in the weeks and months following the accident at Three Mile Island, you recall stories from farmers and other residents living in the vicinity of the plant who described diverse irregularities in the health of domestic animals and in populations of wildlife there. For some, these reports left a lasting impression of conditions near the site of the accident.

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Nuclear Regulator Commission conducted an investigation into these reports. Because the levels of radiation released during the accident were barely above background levels, it was going to be difficult to detect any changes in animals or plants that could be definitively linked to operations at Three Mile Island or the accident there.

Upon evaluating cases for which sufficient data had been preserved or animals were available for examination, investigators failed to find any animal deaths, injuries, diseases, deformities, or stillborn young caused by known effects of ionizing radiation exposure. Anemic conditions would have been expected in animals exposed to significant doses of radiation, but cases of anemia were not found. For the animal fatalities reported, their numbers generally fell within the expected mortality rates for breeding, raising, and keeping the species involved. For the cases examined, no link could be made to exposure to ionizing radiation or byproducts released during the operation of T.M.I. or the accident at Unit 2. Instead of a pattern of mortality and illness consistent with ionizing radiation exposure, investigators instead found a wide-variety of problems considered common to animal keeping.

During the investigation, some of the causes for domestic animal afflictions were identified and, when possible, proper remedies were recommended. Animal husbandry errors, accidents, and disease accounted for most of the deaths, disabilities, and reproduction failures in domestic animals. The occurrence of stillborn or deformed pets was attributed to a variety of diseases and developmental problems that are frequently associated with the symptoms described by pet owners. Poultry eggs that failed to hatch were believed to be infertile or were not maintained at the proper temperature during incubation. Many of the physical ailments in adult dairy cows were traced to mineral deficiencies in the feed. Cases of rickets were found among steers at two different farms. Supplements mitigated these abnormalities in the involved herds. Some cows were found to be suffering from bacterial or viral infections. A few dairy animals had developed mastitis, an inflammation often caused by bacterial infection of the udders. Following diagnosis, herdsmen were able to initiate treatment. Among livestock, fertility and reproductive deficiencies were generally traced to nutritional shortcomings or disease. Those farmers needing further help troubleshooting breeding difficulties were referred to the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture’s Diagnostic Lab.

The majority of people not living in the lower Susquehanna valley at the time paid little attention to the results of the investigations. Such reports are often lengthy and boring, not as exciting as the stories of mutants and catastrophe, and not as memorable. Naturally, the closer you lived to T.M.I., the more informed you probably were about it; you knew first-hand how life was both before and after the accident. Those living elsewhere were sometimes left with exaggerated recollections based upon those initial news stories from the scene.

While traveling some years ago, Uncle Ty was astounded by the perception folks from outside Pennsylvania had of the place he calls home. He told us of one incident in particular. Uncle Ty had gone to the South Bronx in New York City to participate in an “End the Violence” protest. Gunfire and murder were an occurrence of epidemic proportions on street corners there at the time. It turned out that the protest was a poorly attended flop. It happened to be Bat Day at Yankee Stadium, so everyone had gone there instead. During his extended lunch break, Uncle Ty struck up a conversation with a local, a likeable public safety worker who lived and worked in the South Bronx. Ty expressed some sympathy for the stressful conditions the fellow had to endure as a resident there. The guy appreciated his sentiments, but didn’t think he had it too tough. When Ty told him that his home was near Three Mile Island, the guy shook his head in pity and said, “yeah, I hear it’s pretty bad out there, all the two-headed cows walkin’ around and s…”. A guy from one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the country felt really sorry for him. Even Uncle Ty was caught off guard by that one, but it wasn’t the last time he heard it either.

Today, Uncle Ty has us all pondering. Has he given up on Three Mile Island’s grand towers as the primary factor affecting all meteorological irregularities in the lower Susquehanna? Will we ever hear of a cooling tower induced drought again? What will he turn to? It’ll have to be something big. A causative force that no one can quite prove or disprove, mysterious enough to keep everyone guessing if he really knows something no one else knows. I wonder what it’ll be. No matter what it is, it just won’t be the same as hearing, “Man, don’t you know? T.M.I. did it.”

SOURCES

Gears, G. E., G. Laroche, et al. (1980) Investigations of Reported Plant and Animal Health Effects in the Three Mile Island Area. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Las Vegas, NV.