A Pre-dawn Thunderstorm and a Fallout of Migrating Birds

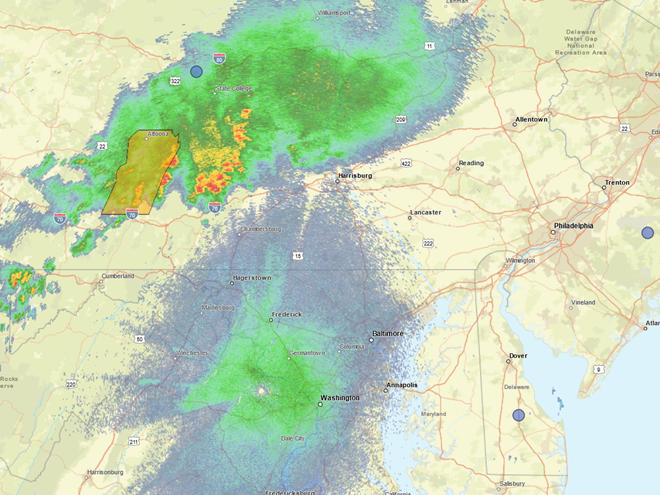

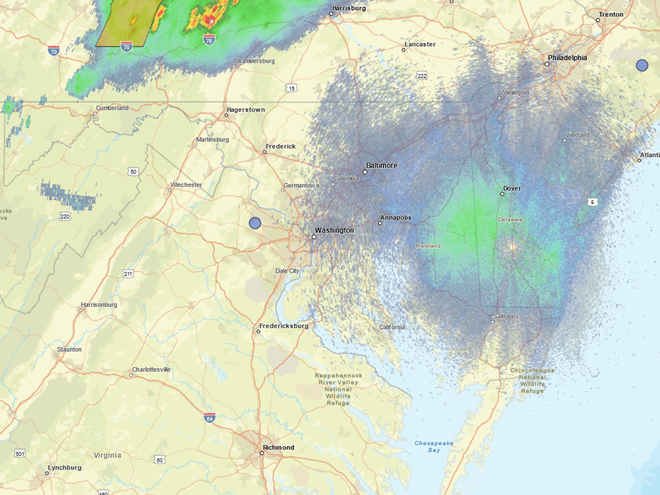

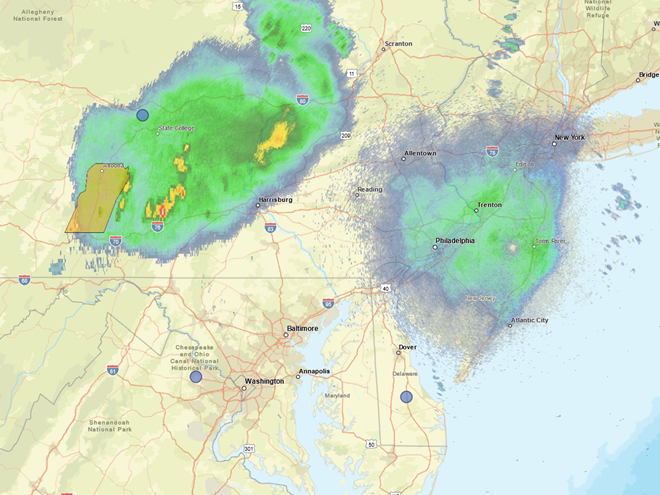

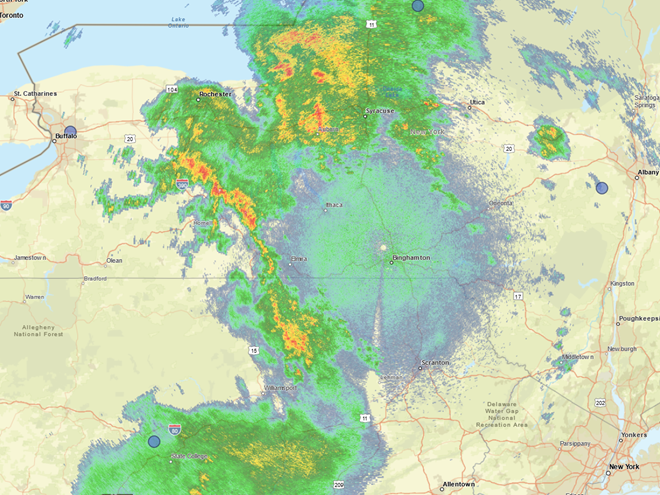

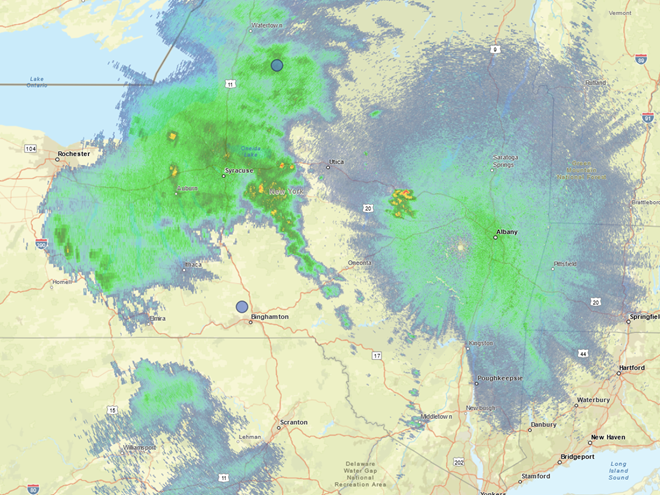

In recent days, the peak northbound push of migratory birds that includes the majority of our colorful Neotropical species has been slowed to a trickle by the presence of rain, fog, and low overcast throughout the Mid-Atlantic States. Following sunset last evening, the nocturnal flight resumed—only to be grounded this morning during the pre-dawn hours by the west-to-east passage of a fast-moving line of strong thundershowers. The NOAA/National Weather Service images that follow show the thunderstorms as well as returns created by thousands of migrating birds as they pass through the Doppler Radar coverage areas that surround the lower Susquehanna valley.

Just after 4 A.M., flashes of lightning in rapid succession repeatedly illuminated the sky over susquehannawildlife.net headquarters. Despite the rumbles of thunder and the din of noises typical for our urban setting, the call notes of nocturnal migrants could be heard as these birds descended in search of a suitable place to make landfall and seek shelter from the storm. At least one Wood Thrush and a Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus) were in the mix of species passing overhead. A short time later at daybreak, a Great Crested Flycatcher was heard calling from a stand of nearby trees and a White-crowned Sparrow was seen in the garden searching for food. None of these aforementioned birds is regular here at our little oasis, so it appears that a significant and abrupt fallout has occurred.

Looks like a good day to take the camera for a walk. Away we go!

There’s obviously more spring migration to come, so do make an effort to visit an array of habitats during the coming weeks to see and hear the wide variety of birds, including the spectacular Neotropical species, that visit the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed each May. You won’t regret it!

Prescribed Fire: Controlled Burns for Forest and Non-forest Habitats

Homo sapiens owes much of its success as a species to an acquired knowledge of how to make, control, and utilize fire. Using fire to convert the energy stored in combustible materials into light and heat has enabled humankind to expand its range throughout the globe. Indeed, humans in their furless incomplete mammalian state may have never been able to expand their populations outside of tropical latitudes without mastery of fire. It is fire that has enabled man to exploit more of the earth’s resources than any other species. From cooking otherwise unpalatable foods to powering the modern industrial society, fire has set man apart from the rest of the natural world.

In our modern civilizations, we generally look at the unplanned outbreak of fire as a catastrophe requiring our immediate intercession. A building fire, for example, is extinguished as quickly as possible to save lives and property. And fires detected in fields, brush, and woodlands are promptly controlled to prevent their exponential growth. But has fire gone to our heads? Do we have an anthropocentric view of fire? Aren’t there naturally occurring fires that are essential to the health of some of the world’s ecosystems? And to our own safety? Indeed there are. And many species and the ecosystems they inhabit rely on the periodic occurrence of fire to maintain their health and vigor.

Man has been availed of the direct benefits of fire for possibly 40,000 years or more. Here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the earliest humans arrived as early as 12,000 years ago—already possessing skills for using fire. Native plants and animals on the other hand, have been part of the ever-changing mix of ecosystems found here for a much longer period of time—millions to tens of millions of years. Many terrestrial native species are adapted to the periodic occurrence of fire. Some, in fact, require it. Most upland ecosystems need an occasional dose of fire, usually ignited by lightning (though volcanism and incoming cosmic projectiles are rare possibilities), to regenerate vegetation, release nutrients, and maintain certain non-climax habitat types.

But much of our region has been deprived of natural-type fires since the time of the clearcutting of the virgin forests during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This absence of a natural fire cycle has contributed to degradation and/or elimination of many forest and non-forest habitats. Without fire, a dangerous stockpile of combustible debris has been collecting, season after season, in some areas for a hundred years or more. Lacking periodic fires or sufficient moisture to sustain prompt decomposition of dead material, wildlands can accumulate enough leaf litter, thatch, dry brush, tinder, and fallen wood to fuel monumentally large forest fires—fires similar to those recently engulfing some areas of the American west. So elimination of natural fire isn’t just a problem for native plants and animals, its a potential problem for humans as well.

To address the habitat ailments caused by a lack of natural fires, federal, state, and local conservation agencies are adopting the practice of “prescribed fire” as a treatment to restore ecosystem health. A prescribed fire is a controlled burn specifically planned to correct one or more vegetative management problems on a given parcel of land. In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is used to…

-

-

- Eliminate dangerous accumulations of combustible fuels in woodlands.

- Reduce accumulations of dead plant material that may harbor disease.

- Provide top kill to promote oak regeneration.

- Regenerate other targeted species of trees, wildflowers, grasses, and vegetation.

- Kill non-native plants and promote growth of native plants.

- Prevent succession.

- Remove woody growth and thatch from grasslands.

- Promote fire tolerant species of plants and animals.

- Create, enhance, and/or manage specialized habitats.

- Improve habitat for rare species (Regal Fritillary, etc.)

- Recycle nutrients and minerals contained in dead plant material.

-

Let’s look at some examples of prescribed fire being implemented right here in our own neighborhood…

In Pennsylvania, state law provides landowners and crews conducting prescribed fire burns with reduced legal liability when the latter meet certain educational, planning, and operational requirements. This law may help encourage more widespread application of prescribed fire in the state’s forests and other ecosystems where essential periodic fire has been absent for so very long. Currently in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is most frequently being employed by state agencies on state lands—in particular, the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources on State Forests and the Pennsylvania Game Commission on State Game Lands. Prescribed fire is also part of the vegetation management plan at Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation and on the land holdings of the Hershey Trust. Visitors to the nearby Gettysburg National Military Park will also notice prescribed fire being used to maintain the grassland restorations there.

For crews administering prescribed fire burns, late March and early April are a busy time. The relative humidity is often at its lowest level of the year, so the probability of ignition of previous years’ growth is generally at its best. We visited with a crew administering a prescribed fire at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area last week. Have a look…

Prescribed burns aren’t a cure-all for what ails a troubled forest or other ecosystem, but they can be an effective remedy for deficiencies caused by a lack of periodic episodes of naturally occurring fire. They are an important option for modern foresters, wildlife managers, and other conservationists.

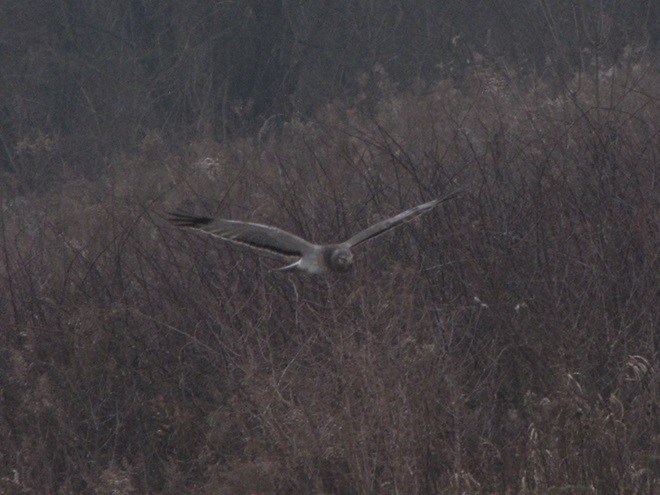

The Fog of a January Thaw

As week-old snow and ice slowly disappears from the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed landscape, we ventured out to see what might be lurking in the dense clouds of fog that for more than two days now have accompanied a mid-winter warm spell.

If scenes of a January thaw begin to awaken your hopes and aspirations for all things spring, then you’ll appreciate this pair of closing photographs…

Want Healthy Floodplains and Streams? Want Clean Water? Then Make Room for the Beaver

I’m worried about the beaver. Here’s why.

Imagine a network of brooks and rivulets meandering through a mosaic of shrubby, sometimes boggy, marshland, purifying water and absorbing high volumes of flow during storm events. This was a typical low-gradient stream in the valleys of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed in the days prior to the arrival of the trans-Atlantic human migrant. Then, a frenzy of trapping, tree chopping, mill building, and stream channelization accompanied the east to west waves of settlement across the region. The first casualty: the indispensable lowlands manager, the North American Beaver (Castor canadensis).

Without the widespread presence of beavers, stream ecology quickly collapsed. Pristine waterways were all at once gone, as were many of their floral and faunal inhabitants. It was a streams-to-sewers saga completed in just one generation. So, if we really want to restore our creeks and rivers, maybe we need to give the North American Beaver some space and respect. After all, we as a species have yet to build an environmentally friendly dam and have yet to fully restore a wetland to its natural state. The beaver is nature’s irreplaceable silt deposition engineer and could be called the 007 of wetland construction—doomed upon discovery, it must do its work without being noticed, but nobody does it better.

Few landowners are receptive to the arrival of North American Beavers as guests or neighbors. This is indeed unfortunate. Upon discovery, beavers, like wolves, coyotes, sharks, spiders, snakes, and so many other animals, evoke an irrational negative response from the majority of people. This too is quite unfortunate, and foolish.

North American Beavers spend their lives and construct their dams, ponds, and lodges exclusively within floodplains—lands that are going to flood. Their existence should create no conflict with the day to day business of human beings. But humans can’t resist encroachment into beaver territory. Because they lack any basic understanding of floodplain function, people look at these indispensable lowlands as something that must be eliminated in the name of progress. They’ll fill them with soil, stone, rock, asphalt, concrete, and all kinds of debris. You name it, they’ll dump it. It’s an ill-fated effort to eliminate these vital areas and the high waters that occasionally inundate them. Having the audacity to believe that the threat of flooding has been mitigated, buildings and poorly engineered roads and bridges are constructed in these “reclaimed lands”. Much of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed has now been subjected to over three hundred years-worth of these “improvements” within spaces that are and will remain—floodplains. Face it folks, they’re going to flood, no matter what we do to try to stop it. And as a matter of fact, the more junk we put into them, the more we displace flood waters into areas that otherwise would not have been impacted! It’s absolute madness.

By now we should know that floodplains are going to flood. And by now we should know that the impacts of flooding are costly where poor municipal planning and negligent civil engineering have been the norm for decades and decades. So aren’t we tired of hearing the endless squawking that goes on every time we get more than an inch of rain? Imagine the difference it would make if we backed out and turned over just one quarter or, better yet, one half of the mileage along streams in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed to North American Beavers. No more mowing, plowing, grazing, dumping, paving, spraying, or building—just leave it to the beavers. Think of the improvements they would make to floodplain function, water quality, and much-needed wildlife habitat. Could you do it? Could you overcome the typical emotional response to beavers arriving on your property and instead of issuing a death warrant, welcome them as the talented engineers they are? I’ll bet you could.

Time to Eat

A glimpse of the rowdy guests crowding the Thanksgiving Day dinner table at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters…

A Visit to a Beaver Pond

To pass the afternoon, we sat quietly along the edge of a pond created recently by North American Beavers (Castor canadensis). They first constructed their dam on this small stream about five years ago. Since then, a flourishing wetland has become established. Have a look.

Isn’t that amazing? North American Beavers build and maintain what human engineers struggle to master—dams and ponds that reduce pollution, allow fish passage, and support self-sustaining ecosystems. Want to clean up the streams and floodplains of your local watershed? Let the beavers do the job!

Photo of the Day

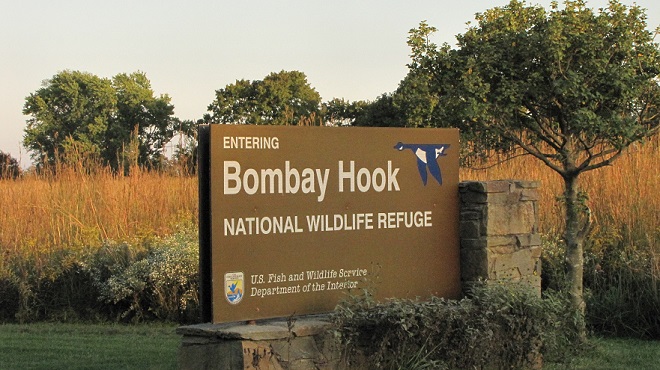

Shorebirds and More at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge

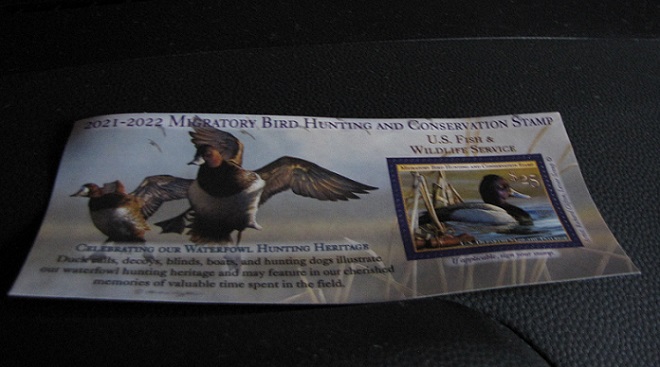

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

Peanuts! Get Your Peanuts!

Forty Years Ago in the Lower Rio Grande Valley: Day Eleven

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY ELEVEN—May 31, 1983

“AOK Camp, Texas — 7 Miles S. of Kingsville”

“Went south to the 1st rest stop south of Sarita — No Tropical Parula. Lots of other birds. We added Summer Tanager and Lesser Goldfinch.”

The Sarita Rest Area along Route 77 was like a little oasis of taller trees in the Texas scrubland. We received reports from the birders we met yesterday at Falcon Dam that recently, Tropical Parula had been seen there. We searched the small area and listened carefully, but to no avail. For these warblers, nesting season was over. We were surprised to find Lesser Goldfinches in the trees. Back in 1983, the coastal plain of Texas was pretty far east for the species. Steve was a bit skeptical when we first spotted them, but once they came into plain view, he was a believer. I recall him finally exclaiming, “They are Lesser Goldfinches.” Summer Tanager was another wonderful surprise. Today, the Sarita Rest Area remains a stopping point for birders in south Texas. Both Lesser Goldfinch and Tropical Parula were seen there this spring.

After our roll of dice at the Sarita Rest Area, we continued south through the King Ranch en route back to Brownsville.

“Saw a Coyote on the way.”

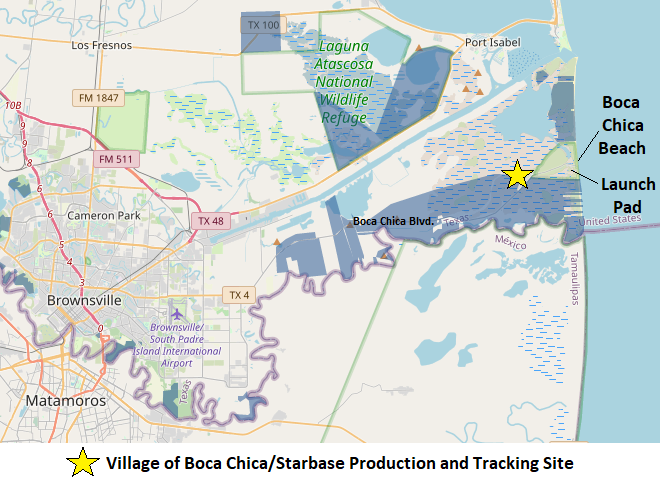

“Took Steve to the airport and drove out to Boca Chica where Harold went swimming.”

The drive from Brownsville out Boca Chica Boulevard to the Gulf of Mexico passes through about 18 miles of the outermost flats of the river delta that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley. This area is of course susceptible to the greatest impacts from tropical weather, especially hurricanes. During our visit, we passed a small cluster of ranch houses about two or three miles from the beach. This was the village known as Boca Chica. Otherwise, the area was desolate and left to the impacts of the weather and to the wildlife.

The mouth of the Rio Grande, and thus the international border with Mexico, was and still is about two miles south of Boca Chica Beach. Before the construction of dams and other flood control measures on the river, the path of the Rio Grande through the alluvium deposits on this outer section of delta would vary greatly. Accumulations of eroded material, river flooding, tides, and storms would conspire to change the landscape prompting the river to seek the path of least resistance and change its course. Surrounding the segments of abandoned channel, these changes leave behind valuable wetlands including not only the resacas of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, but similar features in tidal sections of the outer delta. When left to function in their natural state, deltas manage silt and pollutants in the waters that pass through them using ancient physical, biological, and chemical processes that require no intervention from man.

Harold was determined to go for a swim in the Gulf of Mexico before boarding a flight home. We all liked the beach. Why not? You may remember trips to the shore in the summertime. Back in the pre-casino days, we used to go to Atlantic City, New Jersey, to visit Steel Pier. For the first three quarters of the twentieth century, Steel Pier was the Jersey Shore’s amusement park at sea. There were rides, food stands, arcades, daily concerts with big name acts, diving shows, and ballroom dances.

There were, back then, attractions at Steel Pier that were creatively promoted to give the visitor the impression that they were going to see something more profound or amazing than was was delivered. You know, things advertised to draw you in, but its not quite what you expected.

For example, there was an arcade game promising to show you a chicken playing baseball. Okay, I’ll bite. Turns out the chicken did too. You put your money in the machine and watched as the chicken came out and rounded the diamond eating poultry food as it was offered at each of the bases. Hmmm…to suggest that this was a chicken playing baseball seems like a bit of a stretch.

They had a diving bell there too. Wow! We’ll go below the waves and view the fish, octopi, and other sights through the water-tight windows while we descend to the ocean floor. You would pay to get inside, then they would lower the bell down through a hole in the pier. Once below the rolling surf, you would get to look at the turbid seawater sloshing around at the window like dirty suds in a washing machine. If you were lucky, some trash might briefly get stuck on the glass. To imply that this was a chance to see life beneath waves was B. S., and I don’t mean bathysphere.

Then there was a girl riding a diving horse. You would hike all the way to the end of the pier and watch the preliminary show with these divers plunging through a hole in the deck and into the choppy Atlantic below. They were very good, but no, we never saw Rodney Dangerfield do a “Triple Lindy” there. And then it was time for the finale. Wow, is that horse going to dive in the ocean? How do they get the horse back up on the pier? Forget it. Instead of that, they walked poor Mr. Ed up a ramp into a box, then the girl climbs on his back, the door opens, and she nudges Ol’ Ed to into a plunge followed by a thumping splash into a swimming pool on the deck. Not bad, but not what we were expecting. Since we had to walk almost a quarter of a mile out to sea to get there, they kinda led us to believe that the amazing equine was going to leap into the Atlantic—horse hockey!

Preceding all this fun was a guy back in the early 1930s, William Swan, who, in June 1931, flew a “rocket-powered plane” at Bader Field outside Atlantic City. The plane was actually a glider on which a rocket was fired producing about 50 pounds of thrust to boost it airborne after assistants got it rolling by pushing it. In newspaper articles and on newsreels afterward, he would promote the future of rocket planes carrying passengers across the ocean at 500 miles per hour. Using a glider equipped with pontoons for landing in the ocean, he promised to make several flights daily from Steel Pier. Those who came to see him may have, at best, watched him fire small rockets he had attached to his craft—little more.

What does all this have to do with Boca Chica Beach? It turn out two years later, William Swan is hyping a new innovation—a rocket-powered backpack. He’d demonstrate it during a skydiving exhibition at the Del-Mar Beach Resort, a cluster of 20 cabins and community buildings on Boca Chica Beach. According to his deceptive promotions, Swan would jump out of a plane and light flares as he fell. Then he’d ignite the backpack rocket and land on the shoreline in front of the crowd. The event was expected to draw 3,000 carloads of people. When the big day came, just over 1,000 cars showed up. The event was a bust and the weather was bad, cloudy with a mist over the gulf. During a break in the clouds, the pilot took Swan aloft. Swan ordered him out to sea and to 8,500 feet, a higher altitude than planned. Then he jumped. He dropped the flares, which didn’t then ignite, and neither did the rocket. He opened his chute at 6,000 feet and the crowd watched as Swan drifted into the mist offshore and was never seen again. There were rumors both that he used the stunt as a way to flee to Mexico to start a new life and that he had committed suicide. Others believed he died accidentally. To learn the full story of Billy Swan, check out The Rocketeer Who Never Was, by Mark Wade.

Forward fifty years to our visit to Boca Chica Beach. The Del-Mar Beach Resort, built in the 1920s as a cluster of 20 cabins and a ballroom, was gone. It was destroyed by a hurricane later in the same year Swan disappeared—1933. The resort, which was hoped would be the start of a seaside vacation city, never reopened. In 1983, we saw just a handful of beach goers and the birds, that’s it. One could look down to the south and see the area of the Rio Grande’s mouth and Mexico, but there were no structures of note. It was peaceful and alive with wildlife. We were sorry we didn’t have more time there.

“Here we added Least Tern, Brown Pelican and Sandwich Tern.”

Today, the Village of Boca Chica and Boca Chica Beach are the location of SpaceX’s South Texas Launch Facility. Those of the village’s ranch houses built in 1967 that have survived hurricane devastation over the years have been incorporated into the “Starbase” production and tracking facility. The launch pad and testing area is along the beach just behind the dunes at the end of Boca Chica Boulevard.

The latest launch, just more than a month ago, was the maiden flight of “Starship”, a 394-foot behemoth that is the largest rocket ever flown. The “Super Heavy Booster” first stage’s 33 Raptor engines produce 17.1 million pounds of thrust making Starship the most powerful rocket ever flown. See, things really are bigger in Texas.

Last month’s unmanned orbital test launch ended when the Starship spacecraft failed to separate at staging. As the booster section commenced its roll manuever to return to the launch pad, the entire assembly began tumbling out of control. It exploded and rained debris into the gulf along a stretch of the downrange trajectory.

Development of Starbase is opposed by many due to noise, safety, and environmental concerns. Boca Chica Boulevard (Texas Route 4) is frequently closed due to activity at the launch pad site, thus excluding residents and tourists from visiting the beach. With over 1,200 people already working at Starbase, demand for housing in the Brownsville area has increased. Some have accused SpaceX CEO Elon Musk of promoting gentrification of the area—running up housing prices to force out the lower-income residents. He has responded with a vision of a new city at Boca Chica, his “space port”.

Does history have an applicable lesson for us here? When Musk talks about going to the Moon and Mars, or ferrying a hundred people around the world on his Starship, is it just another Steel Pier-style deception? Is Musk a modern-day William Swan? A very talented marketer? Could be. And is the whole thing setting up a large-scale replay of the Del-Mar Beach Resort’s demise in 1933? Is building a city on the outer edges of a river delta asking for an outcome similar to the one suffered by New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina? It’s likely. After all, building on or near a beach, floodplain, or delta is a short-sighted venture to begin with. If the party doing the developing doesn’t suffer the consequences of defying the laws of nature, one of the poor suckers in the successive line of buyers and occupants will. This isn’t rocket science folks. Its weather, climate, and erosion, and its been altering coastlines, river courses, and the composition and distribution of life forms on this planet for millions of years. And guess what. These factors will continue to alter Earth for millions of years more after man the meddler is long gone. You’re not going to stop their effects, and you’re not going to escape their wrath by ignoring them. So if you’re smart, you’ll get out of their way and stay there!

Billy Swan was probably broke when he came to Boca Chica. He reportedly borrowed 20 bucks from the resort operator just to cover his personal expenses during his backpack rocket event. Elon Musk comes to Boca Chica with over 100 billion dollars and capital from other private investors to boot. Despite some obvious exaggerations about colonizing the Moon, Mars, and other celestial bodies, he just might be able to at least get people there for short-term visits. And that’s quite an accomplishment.

“Then took Harold to the airport. We left him at 3:30 and headed north on Route 77, got as far as Victoria. Had a flat on the way. Larry had the spare on in 10 minutes. We stopped at a picnic area for the nite, because we could not find the camping area.”

If we were going to have a flat, we had it at the right place. We were just outside Raymondville, Texas, at a newly constructed highway interchange. The wide, level shoulder allowed us to get the camper off to the side of the road in a safe place to jack it up and change the tire. Easy. We were thereafter homeward bound.

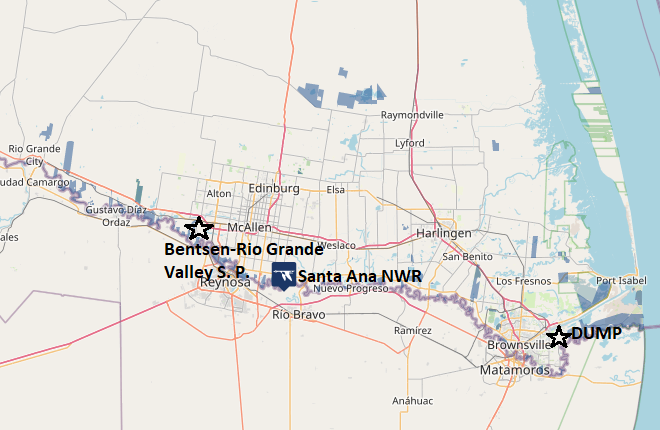

Forty Years Ago in the Lower Rio Grande Valley: Day Four

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY FOUR—May 24, 1983

“AOK Campground—South of Kingsville, Texas”

“Arose at 6:30 A.M. to the tune of Common Nighthawks. After breakfast, we headed for Harlingen. While driving south we saw six pairs of Black-bellied Whistling Ducks. At Harlingen we phoned Father Tom, who is an expert birder for the area.”

As we drove south to Harlingen, much our 100-mile route was through the Laureles division of the King Ranch, the largest ranch in the United States. It covers over 800,000 acres and is larger than the state of Rhode Island. The road there was as straight as an arrow with wire fences on both sides and scrubland as far as the eye could see. Things really are bigger in Texas.

Once in Harlingen, we did two things no one needs to do anymore:

-

-

- Find a coin-operated telephone to place a call to Father Tom.

- Ask Father Tom for the latest tips on the locations of rare and/or target birds.

-

Today, nearly everyone traveling such distances to find birds is carrying a cellular phone and many can use theirs to access internet sites and databases such as eBird to get current sighting information. Back in 1983, Father Tom Pincelli was a dear friend to birders visiting the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Few places had a person who was willing to answer the phone and field inquiries regarding the latest whereabouts of this or that bird. To remain current, he also had to religiously (forgive me for the pun) collect sighting information from the observers with whom he had contact. For locations elsewhere across the country, a birder in 1983 was happy just to have a phone number for a hotline with a tape-recorded message listing the unusual sightings for its covered region. If you were lucky, the volunteer logging the sightings would be able to update the tape once a week. For those who dialed his number, Father Tom provided an exceptionally personal experience.

Since 1983, Father Tom Pincelli, also known as “Father Bird”, has tirelessly promoted birding and conservation throughout the Lower Rio Grande Valley. His efforts have included hosting a P.B.S. television program and writing columns for local newspapers. He has been instrumental in developing the annual Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival. The public sentiment he has generated for the birding paradise that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley has helped facilitate the acquisition and/or protection of many key parcels of land in the region.

“After receiving information on locations of Tropical Parula, Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, Hook-billed Kite, Brown Jay, and Clay-colored Robin, we went on to check out the Brownsville Airport where we will meet Harold and Steve Thursday noon.”

If we were going to see these five species in the American Birding Association listing area, then we would have to see them in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. All five were target birds for each of us, including Harold who had few other possibilities for new species on the trip. Father Tom provided us with tips for finding each.

I noticed as we began moving around Harlingen and Brownsville that Russ was swiftly getting his bearings—he had been here before and was starting to remember where things were. His ability to navigate his way around allowed us to keep moving and see a lot in a short time.

In Harlingen, we easily found Mourning Doves and the non-native Rock Pigeons, species we see regularly in Pennsylvania. We became more enthusiastic about doves and pigeons soon after when we saw the first of the several other species native to south Texas, the diminutive Inca Dove (Columbina inca), also known as the Mexican Dove.

“Next, to the Brownsville Dump to see the White-necked Ravens — Then to Mrs. Benn’s in Brownsville for the Buff-bellied Hummingbird. Both lifers for Larry.”

For birders wanting to see a White-necked Raven in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the Brownsville Dump was the place to go. With very little effort—excluding a trip of nearly 2,000 miles to get there—we found them. Today, birders still go to the Brownsville Dump to find White-necked Ravens, though the dump is now called the Brownsville Landfill and the bird is known as the Chihuahuan Raven (Corvus cryptoleucus).

Mrs. Benn’s home was in a verdant residential neighborhood in Brownsville. She welcomed birders to come and see the Buff-bellied Hummingbirds that visited her feeder filled with sugar water. I don’t recall whether or not she kept a guest book for visitors to sign, but if she did, it would have included hundreds—maybe thousands—of names of people from all over North America who came to her garden to get a look at a Buff-bellied Hummingbird. After arriving, we waited a short time and sure enough, we watched a Buff-bellied Hummingbird (Amazilia yucatanensis) sipping Mrs. Benn’s home-brewed nectar from her glass feeder. This emerald hummingbird is primarily a Mexican species with a breeding range that extends north into the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. When not breeding, a few will wander north and east along the Gulf Coastal Plain as far as Florida.

Other finds at Mrs Benn’s included White-winged Dove (Zenaida asiatica), Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens), Brown-crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus tyrannulus), and Black-crested Titmouse (Baeolophus atricristatus), a species also known as Mexican Titmouse.

The Lower Rio Grande Valley from Rio Grande City east to the Gulf of Mexico is actually the river’s outflow delta. At least six historic channels have been delineated in Texas on the north side of the river’s present-day course. An equal number may exist south of the border in Mexico. Hundreds of oxbow lakes known as “resacas” mark the paths of the former channels through the delta. Many resacas are the centerpieces of parks, wildlife refuges, and housing developments. Still others are barely detectable after being buried in silt deposits left by the meandering river. Channelization, land disturbances related to agriculture, and a boom in urbanization throughout the valley have disconnected many of the most recently formed resacas from the river’s floodplain, preventing them from absorbing the impact of high-water events. These alterations to natural morphology can severely aggravate flooding and water pollution problems.

“On to Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. We walked to Pintail Lake and saw 6 Black-bellied Whistling Ducks and 2 Mississippi Kites and 1 Pied-billed Grebe. We drove the route thru the park with great results—Anhingas, Least Grebe, and more Black-bellied Whistling Ducks.

Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge on the Rio Grande is not only a birder’s mecca, 300 species of butterflies have been identified there. That’s half the species known to occur in the United States! Its subtropical riparian forest and resaca lakes provide habitat for hundreds of migratory and resident bird species including many Central and South American species that reach the northern limit of their range in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Two endangered cats occur in the park—the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and the Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi).

We saw no cats at Santa Ana, but did quite well with the birds. Our list included the species listed above plus Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis); Louisiana Heron, now known as Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor); Plain Chachalacas; Purple Gallinule; Common Gallinule (Gallinula galeata); American Coot; Killdeer; Greater Yellowlegs; the coastal Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla); and its close relative of the central flyway and continental interior, the Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan). Others finds were White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, Inca Dove, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Ladder-backed Woodpecker (Dryobates scalaris), Brown-crested Flycatcher, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and House Sparrow. A real standout was the colorful Green Jay (Cyanocorax luxosus), yet another tropical Central American species found north only as far as the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

“We were unlucky not to find a campground at McAllen, so we went on to Bentsen State Park where we got a camp spot. After a sauerkraut supper, we birded till dark, then showered and wrote up the log. Very hot today.”

Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, like the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, is located along the Rio Grande river and features dense subtropical riparian forest that grows in the naturally-deposited silt levees of the floodplain surrounding several lake-like oxbow resacas. Montezuma Bald Cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) is a native specialty found there but nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley. During our visit, we marveled at the epiphyte Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) adorning many of the more massive trees in the park. Willows lined much of the river shoreline.

Over time, flood control projects such as man-made dams, drainage ditches, and levees have impaired stormwater capture and aquifer recharge in the floodplain. These alterations to watershed hydrology have resulted in drier soils in many sections of the Lower Rio Grande Valley’s riparian forests. Where drier conditions persist, xeric (dry soil) scrubland plants are slowly overtaking the moisture-dependent species. As a result, the park’s woodlands are composed of trees with a variety of microclimatic requirements—Anaqua (Ehretia anacua), Cedar Elm (Ulmus crassifolia), Texas Ebony (Ebenopsis ebano), hackberry, mesquite, Mexican Ash (Fraxinus berlandieriana), retama, and tepeguaje are the principle species. The park’s subtropical Texas Wild Olive (Cordia boissieri) grows in the wild nowhere north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

While a majority of birders visiting Benten-Rio Grande State Park come to see the more tropical specialties of the riparian woods, searching the brushy habitat of the park’s scrubland can afford one the opportunity to see species typical of the southwestern United States and deserts of Mexico. This scrubland of the Lower Rio Grande Valley is part of the Tamaulipan Mezquital ecoregion, an area of xeric (dry soil) shrublands and deserts that extends northwest from the delta through most of south Texas and into the bordering provinces of northeastern Mexico.

Our campsite was located in prime birding habitat. We were a short walk away from one of the park’s flooded oxbow resacas and vegetation was thick along the roadsides. It was no surprise that the place abounded with birds. An evening stroll yielded Plain Chachalaca, White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, White-fronted Dove, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Brown-crested Flycatcher, Green Jay, Altamira Oriole, Great-tailed Grackle, and Bronzed Cowbird (Molothrus aeneus). At nightfall, we listened to the calls of an Eastern Screech Owl (Megascops asio), Common Nighthawks, and Common Pauraque (Nyctidromus albicollis), a nightjar of Central and South America that nests only as far north as the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The Common Pauraque is the tropical counterpart of the Eastern Whip-poor-will, a Neotropical migrant that nests in scattered forest locations throughout eastern North America.

I would note that we saw no “snowbirds”—long-term vacationers from the northern states and Canada who fill the park through the cooler months of fall, winter, and spring. They were gone for the summer. But for a few other friendly folks, we had the entire campground to ourselves for the duration of our stay.

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

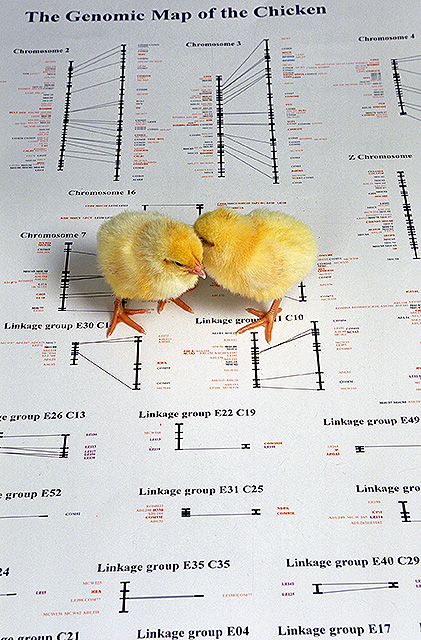

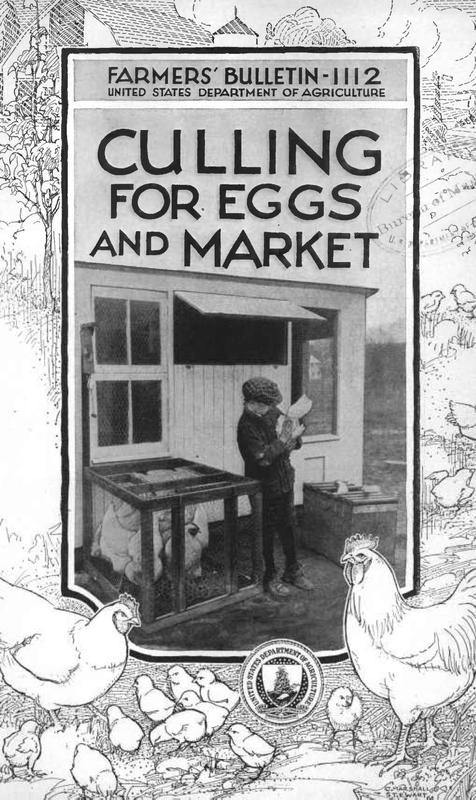

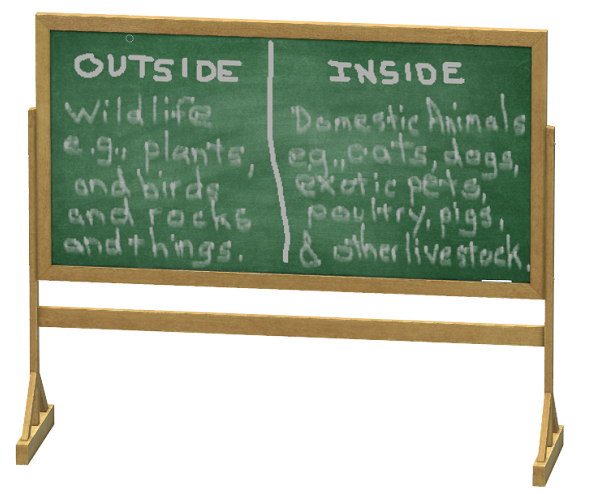

Are Your Eggs All They’re Cracked Up To Be?

Looks like I’m gonna be in the doghouse again—this time by way of the hen house. But why should I care? Here we go.

A few weeks ago, back when eggs were still selling for less than five dollars a dozen, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture renewed calls for owners and caretakers of outdoor flocks of domestic poultry (backyard chickens) to keep their birds indoors to protect them from the spread of bird flu—specifically “Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza” (H.P.A.I.). At least one story edited and broadcast by a Susquehanna valley news outlet gave the impression that “vultures and hawks” are responsible for the spread of avian flu in chickens. To see if recent history supports such a deduction, let’s have a look at the U.S.D.A.’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s 2022-2023 list of the detection of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in birds affected in counties of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed in Pennsylvania.

H.P.A.I. 2022 Confirmed Detections as of January 13, 2023

This listing includes date of detection, county of collection, type/species of bird, and number of birds affected. WOAH (World Organization for Animal Health) birds include backyard poultry, game birds raised for eventual release, domestic pet species, etc.

12/30/2022 Adams Black Vulture

12/15/2022 Lancaster Canada Goose

12/15/2022 Lebanon Black Vulture

12/15/2022 Adams Black Vulture (3)

11/8/2022 Cumberland Black Vulture (4)

11/4/2022 Dauphin WOAH Non-Poultry (130)

10/19/2022 Dauphin Captive Wild Rhea (4)

10/17/2022 Adams Commercial Turkey (15,100)

10/11/2022 Adams WOAH Poultry (2,800)

9/30/2022 Lancaster Mallard

9/30/2022 Lancaster Mallard

9/29/2022 Lancaster WOAH Non-Poultry (180)

9/29/2022 York Commercial Turkey (25,900)

8/24/2022 Dauphin Captive Wild Crane

7/15/2022 Lancaster Great Horned Owl

7/15/2022 York Bald Eagle

7/15/2022 Dauphin Bald Eagle

6/16/2022 Dauphin Black Vulture

6/16/2022 Dauphin Black Vulture (4)

5/31/2022 Lancaster Black Vulture (2)

5/31/2022 Lancaster Black Vulture

5/10/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (72,300)

4/29/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Duck (19,300)

4/27/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Broiler (18,100)

4/26/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (307,400)

4/22/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Broiler (50,300)

4/20/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (1,127,700)

4/20/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (879,400)

4/15/2022-Lncstr-Commercial Egg Layer (1,380,500)

In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, it’s pretty obvious that the outbreak of avian flu got its foothold inside some of the area’s big commercial poultry houses. Common sense tells us that hawks, vultures, and other birds didn’t migrate north into the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed carrying bird flu, then kick in the doors of the enclosed hen houses to infect the flocks of chickens therein. Anyone paying attention during these past three years knows that isolation and quarantine are practices more easily proposed than sustained. Human footprints are all over the introduction of this infection into these enormous flocks. Simply put, men don’t wipe their feet when no one is watching! The outbreak of bird flu in these large operations was brought under control quickly, but not until teams of state and federal experts arrived to assure proper sanitary and isolation practices were being implemented and used religiously to prevent contaminated equipment, clothing, vehicles, feed deliveries, and feet from transporting virus to unaffected facilities. Large poultry houses aren’t ideal enclosures with absolute capabilities for excluding or containing viruses and other pathogens. Exhaust systems often blow feathers and waste particulates into the air surrounding these sites and present the opportunity for flu to be transported by wind or service vehicles and other conveyances that pass through contaminated ground then move on to other sites—both commercial and non-commercial. Waste material and birds (both dead and alive) removed from commercial poultry buildings can spread contamination during transport and after deposition. The sheer volume of the potentially infected organic material involved in these large poultry operations makes absolute containment of an outbreak nearly impossible.

Looking at the timeline created by the list of U.S.D.A. detections, the opportunity for bird flu to leave the commercial poultry loop probably happened when wild birds gained access to stored or disposed waste and dead animals from an infected commercial poultry operation. For decades now, many poultry operations have dumped dead birds outside their buildings where they are consumed by carrion-eating mammals, crows, vultures, Bald Eagles, and Red-tailed Hawks. For these species, discarded livestock is one of the few remaining food sources in portions of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where high-intensity farming has eliminated other forms of sustenance. They will travel many miles and gather in unnatural concentrations to feast on these handouts—creating ideal circumstances for the spread of disease.

The sequence of events indicated by the U.S.D.A. list would lead us to infer that vultures and Bald Eagles were quick to find and consume dead birds infected with H5N1—either wild species such as waterfowl or more likely domestic poultry from commercial operations or from infectious backyard flocks that went undetected. As the report shows, Black Vultures in particular seem to be susceptible to morbidity. Their frequent occurrence as victims highlights the need to dispose of potentially infectious poultry carcasses properly—allowing no access for hungry wildlife including scavengers.

The positive test on a Great Horned Owl is an interesting case. While the owl may have consumed an infected wild bird such as a crow, there is the possibility that it consumed or contacted a mammalian scavenger that was carrying the virus. Aside from rodents and other small mammals, Great Horned Owls also prey upon Striped Skunks with some regularity. Most of the dead poultry from flu-infected commercial flocks was buried onsite in rows of above-ground mounds. Skunks sniff the ground for subterranean fare, digging up invertebrates and other food. Buried chickens at a flu disposal site would constitute a feast for these opportunistic foragers. A skunk would have no trouble at all finding at least a few edible scraps at such a site. Then a Great Horned Owl could easily seize and feed upon such a flu virus-contaminated skunk.

BACKYARD POULTRY

Before we proceed, the reader must understand the seldom-stated and never advertised mission of the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture—to protect the state’s agriculture industry. That’s it; that’s the bottom line. Regulation and enforcement of matters under the purview of the agency have their roots in this goal. While they may also protect the public health, animal health, and other niceties, the underlying purpose of their existence in its current manifestation is to protect the agriculture industry(s) as a whole.

This is not a trait unique to the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. It is at the core of many other federal and state agencies as well. Following the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle in 1906, a novel decrying “wage slavery” in the meat packing industry, the federal government took action, not for the purpose of improving the working conditions for labor, but to address the unsanitary food-handling practices described in the book by creating an inspection program to restore consumer confidence in the commercially-processed meat supply so that the industry would not crumble.

Locally, few things make the dairy industry and the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture more nervous than small producers selling “raw milk”. In the days before pasteurization and refrigeration, people were frequently sickened and some even died from drinking bacteria-contaminated “raw milk”. In Pennsylvania, the production and sale of dairy products including “raw milk” is closely regulated and requires a permit. Retention of a permit requires submitting to inspections and passing periodic herd and product testing. Despite the dangers, many consumers continue to buy “raw milk” from farms without permits. These sales are like a ticking time bomb. The bad publicity from an outbreak of food-borne illness traced back to a dairy product—even if it originated in an “outlaw” operation—could decimate sales throughout the industry. Because just one sloppy farm selling “raw milk” could instantly erode consumer confidence and cause an industry-wide collapse of the market resulting in a loss of millions of dollars in sales, it is a deeply concerning issue.

Enter the backyard chicken—a two-fold source of anxiety for the poultry industry and its regulators. Like unregulated meat and dairy products, eggs and meat from backyard poultry flocks are often marketed without being monitored for the pathogens responsible for the transmission of food-borne illness. From the viewpoint of the poultry industry, this situation poses a human health risk that in the event of an outbreak, could erode consumer confidence, not only in homegrown organic and free-range products, but in the commercial line of products as well. Consumers can be very reactive upon hearing news of an outbreak, recalling few details other than “the fowl is foul”— then refraining from buying poultry products. The second and currently most concerning source of trepidation among members of the poultry industry though is the threat of avian flu and other diseases being harbored in and transmitted via flocks of backyard birds.

The Green Revolution, the post-World War II initiative that integrated technology into agriculture to increase yields and assure an adequate food supply for the growing global population, brought changes to the way farmers raised poultry for market. Small-scale poultry husbandry slowly disappeared from many farms. Instead, commercial operations concentrated birds into progressively-larger indoor flocks to provide economy of scale. Over time, genetics and nutrition science have provided the American consumer with a line of readily available high-quality poultry products at an inexpensive price. Within these large-scale operations, poultry health is closely monitored. Though these enclosures may house hundreds of thousands of birds, the strategy during an outbreak of communicable disease is to contain an outbreak to the flock therein, writing it off so to speak to prevent the pathogens from finding their way into the remainder of the population in a geographic area, thus saving the industry at the expense of the contents of a single operation. Adherence to effective biosecurity practices can contain outbreaks in this way.

The renewed popularity of backyard poultry is a reversal of the decades-long trend towards reliance on ever-larger indoor operations for the production of birds and eggs. But backyard flocks may make less-than-ideal neighbors for commercial operations, particularly when birds are left to roam outdoors. Visitors to properties with roaming chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys may pick up contamination on their shoes, clothing, tires, and equipment, then transmit the pathogenic material to flocks at other sites they visit without ever knowing it. Even the letter carrier can carry virus from a mud puddle on an infected farm to a grazing area on a previously unaffected one. Unlike commercial operations, hobby farms frequently buy, sell, and trade livestock and eggs without regard to disease transmission. The rate of infection in these operations is always something of a mystery. No state or county permits are required for keeping small numbers of poultry and outbreaks like avian flu are seldom reported by caretakers of flocks of home-raised birds, though their occurrence among them may be widespread. The potential for pathogens like avian flu virus circulating long-term among flocks of backyard poultry in close proximity to commercial houses is a real threat to the industry.

There are a variety of motivations for tending backyard poultry. While for some it is merely a form of pet keeping, others are more serious about the practice—raising and breeding exotic varieties for show and trade. Increasingly, backyard flocks are being established by people seeking to provide their own source of eggs or meat. For those with larger home operations, supplemental income is derived from selling their surplus poultry products. Many of these backyard enthusiasts are part of a movement founded on the belief that, in comparison to commercially reared birds, their poultry is raised under healthier and more humane conditions by roaming outdoors. Organic operators believe their eggs and meat are safer for consumption—produced without the use of chemicals. For the movement’s most dedicated “true believers”, the big poultry industry is the antagonist and homegrown fowl is the only hope. It’s similar to the perspective members of the “raw milk” movement have toward pasteurized milk. True believers are often willing to risk their health and well-being for the sake of the cause, so questioning the validity of their movement can render a skeptic persona non grata.

For the consumer, the question arises, “Are eggs and poultry from the small-scale operations better?”

While many health-conscious animal-friendly consumers would agree to support the small producer from the local farm ahead of big business, the reality of supplying food for the masses requires the economy of scale. The billions of people in the world can’t be fed using small-scale and/or organic growing methods. The Green Revolution has provided record-high yields by incorporating herbicides, insecticides, plastic, and genetic modification into agriculture. To protect livestock and improve productivity, enormous indoor operations are increasingly common. Current economics tell the story—organic production can’t keep up with demand, that’s why the prices for items labelled organic are so much higher.

To the consumer, buying poultry raised outdoors is an appealing option. Compared to livestock crowded into buildings, they feel good about choosing products from small operations where birds roam free and happy in the sunshine.

But is the quality really better? Some research indicates not. Salmonella outbreaks have been traced back to poultry meat sourced from small unregulated operations. Studies have found dioxins in eggs produced by hens left to forage outdoors. The common practice of burning trash can generate a quantity of ash sufficient to contaminate soils with dioxins, chemical compounds which persist in the environment and in the fatty tissue of animals for years. The presence of elevated levels of dioxins in eggs from outdoor grazing operations may pose a potential consumer confidence liability for the entire egg industry.

Birds raised or kept in an outdoor zoo or backyard poultry setting can be susceptible to viruses and other pathogens when wild birds including vultures and hawks become attracted to the captives’ food and water when it is placed in an accessible location. In addition, hunting and scavenging birds are opportunistic— attracted to potential food animals when they perceive vulnerability. Selective breeding under domestication has rendered food poultry fat, dumb, and too genetically impaired for survival in the wild. These weaknesses instantly arouse the curiosity of raptors and other predators whose function in the food web is to maintain a healthy population of animals at lower tiers of the food chain by selectively consuming the sickly and weak. In settings such as those created by high-intensity agriculture and urbanization, wild birds may find the potential food sources offered by outdoor zoos and backyard poultry irresistible. As a result they may perch, loaf, and linger around these locations—potentially exposing the captive birds to their droppings and transmission of bird flu and other diseases.

While outdoor poultry operations usually raise far fewer birds than their commercial counterparts, their animals are still kept in densities high enough to promote the rapid spread of microbiological diseases. Clusters of outdoor flocks can become a reservoir of pathogens with the capability of repeatedly circulating disease into populations of wild birds and even into commercial poultry operations—threatening the industry and food supply for millions of people. For this reason, state and federal agencies are encouraging operators to keep backyard poultry indoors—segregated from natural and anthropogenic disease vectors and conveyances that might otherwise visit and interact with the flock.

BACK TO THE FUTURE?—NOT LIKELY

The hobby farmer, the homesteader, the pet keeper, and the consumer seldom realize what the modern farmer is coming to know—domestic livestock must be segregated from the sources of contamination and disease that occur outdoors. Adherence to this simple concept helps assure improved health for the animals and a safer food supply for consumers. In the future, outdoor production of domestic animals, particularly those used as a food supply, is likely to be classified as an outdated and antiquated form of animal husbandry.

THE THREAT FROM PRIONS

If there are three things the world learned from the SARS CoV-2 (Covid-19) epidemic, it’s that 1) eating or handling bush meat can bring unwanted surprises, 2) dense populations of very mobile humans are ideal mediums for uncontrolled transmission of disease, and 3) quarantine is easier said than done.

If you think viruses are bad, you don’t even want to know about prions. Prions are a prime example of why now is a good time to begin housing domestic animals, including pets, indoors to segregate them from wildlife. And prions are a good example of why we really ought to think twice about relying on wild animals as a source of food. Prions may make us completely rethink the way we interact with animals of any kind—but we had better do our thinking fast because prions turn the brains of their victims into Swiss cheese.

Diseases caused by prions are rapidly progressing neurodegenerative disorders for which there is no cure. Prions are an abnormal isoform of a cellular glycoprotein. They are currently rare, but prions, because they are not living entities, possess the ability to begin accumulating in the environment. They not only remain in detritus left behind by the decaying carcasses of afflicted animals, but can also be shed in manure—entering soils and becoming more and more prevalent over time. Some are speculating that they could wind up being man’s downfall.

The Centers for Disease Control lists these human afflictions caused by prions…

-

-

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD)

- Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD)

- Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker Syndrome

- Fatal Familial Insomnia

- Kuru

-

The Centers for Disease Control lists these prion-caused ailments of other animals…

-

-

- Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE)

- Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD)

- Scrapie

- Transmissible Mink Encephalopathy

- Feline Spongiform Encephalopathy

- Ungulate Spongiform Encephalopathy

-

SOURCES

Schoeters, Greet, and Ron Hoogenboom. 2006. Contamination of Free-range Chicken Eggs with Dioxins and Dioxin-like Polychlorinated Biphenyls. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. (10):908-14.

Szczepan, Mikolajczyk, Marek Pajurek, Malgorzata Warenik-Bany, and Sebastian Maszewski. 2021. Environmental Contamination of Free-range Hen with Dioxin. Journal of Veterinary Research. 65(2):225-229.

U.S.D.A. Animal and Plant Inspection Service. 2022 Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-2022/2022-hpai-commercial-backyard-flocks as accessed January 14, 2023.

U.S.D.A. Animal and Plant Inspection Service. 2022 Confirmations of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-2022/2022-hpai-wild-birds as accessed January 14, 2023.

Photo of the Day

In the Doghouse

Am I the only one who feels like Oliver Wendell Douglas living in an eccentric society overrun by millions of dogs, cats, and other domestic animals that have assumed the identity of Arnold Ziffel?

Just asking.

Migratory Waterfowl on Local Ponds and Lakes

Following the deep freeze of a week ago, temperatures soaring into the fifties and sixties during recent days have brought to mind thoughts of spring. In the pond at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, Green Frogs are again out and about.

But is this really an early spring? Migrating waterfowl indicate otherwise. Having been forced south from the Great Lakes during the bitter cold snap, a variety of our tardy web-footed friends belatedly arrived on the river and on the Susquehanna Flats of upper Chesapeake Bay about ten days ago. Now, rising water from snow melt and this week’s rains have forced many of these ducks onto local lakes and ponds where ice coverage has been all but eliminated by the mild weather. For the most part, these are lingering autumn migrants. Here’s a sample of some of the waterfowl seen during a tour of the area today…

With the worst of winter’s fury still to come, it’s time to say farewell to most of these travelers for a little while. With a little luck, we’ll see them again in March or April.

The Gasoline and Gunpowder Gang’s Second-biggest Holiday of the Year

For members of the gasoline and gunpowder gang in Pennsylvania, the coming two weeks are the second-biggest holiday of the year. Cloaked in ceremonial orange, worshipers of the White-tailed Deity are making their annual pilgrimage into the great outdoors to beat the bushes in search of their idol. For the fortunate among the faithful, their devotion culminates in a testosterone/adrenaline-charged sacrifice of the supreme being.

Remember, emotions run high during this blood-letting festival—sometimes overwhelming secular attributes like logic and rational decision-making. You don’t want to be in the crossfire—so stay out of the woods!

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Emergence of the Turtles

Along the lower Susquehanna, an unseasonably mild day in early spring can provide an observer with the opportunity to witness an annual spectacle seldom seen by the average visitor to the river—concentrations of dozens, sometimes hundreds, of turtles as they emerge from their winter slumber to bathe in the year’s first surge of warm air and sunshine.

Photo of the Day

Five Best Values for Feeding Birds

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

Photo of the Day

A Visit to Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

Photo of the Day

How to Remove a Mole in Just Five Minutes

Some consider them things of beauty. Others reckon them hideous—better kept out of sight and out of mind. They’re moles, and here’s how they’re removed in just five minutes.

Moles—they’re an acquired taste.

Coming Soon, Very Soon: Brood X Periodical Cicadas

Yesterday, a hike through a peaceful ridgetop woods in the Furnace Hills of southern Lebanon County resulted in an interesting discovery. It was extraordinarily quiet for a mid-April afternoon. Bird life was sparse—just a pair of nesting White-breasted Nuthatches and a drumming Hairy Woodpecker. A few deer scurried down the hillside. There was little else to see or hear. But if one were to have a look below the forest floor, they’d find out where the action is.

2021 is an emergence year for Brood X, the “Great Eastern Brood”—the largest of the 15 surviving broods of Periodical Cicadas. After seventeen years as subterranean larvae, the nymphs are presently positioned just below ground level, and they’re ready to see sunlight. After tunneling upward from the deciduous tree roots from which they fed on small amounts of sap since 2004, they’re awaiting a steady ground temperature of about 64 degrees Fahrenheit before surfacing to climb a tree, shrub, or other object and undergo one last molt into an imago—a flying adult.

The woodlots of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed won’t be quiet for long. Loud choruses of male Periodical Cicadas will soon roar through forest and verdant suburbia. They’re looking for love, and they’re gonna die trying to find it. And dozens and dozens of animal species will take advantage of the swarms to feed themselves and their young. Yep, the woods are gonna be a lively place real soon.

Piebald Deer at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area

Except for a few injured stragglers, Snow Geese have departed Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties to continue their journey north to breeding grounds in Canada. The crowds of observers are gone too. So if you’re looking for a reason to pay a visit to a much quieter refuge, here it is—especially if you’re a devoted deer worshiper.

There is at least one white deer being seen on the refuge. That’s right, a white deer. Its unusual color is really becoming conspicuous as the landscape begins turning from shades of gray to various hues of bright green.

If you go, you’ll need binoculars to pick out these uncommon deer. And remember to be very careful when parking and observing along Kleinfeltersville Road. The speeding cars and trucks there can be wickedly dangerous, so give them lots of room.

Forest vs. Woodlot

Let’s take a quiet stroll through the forest to have a look around. The spring awakening is underway and it’s a marvelous thing to behold. You may think it a bit odd, but during this walk we’re not going to spend all of our time gazing up into the trees. Instead, we’re going to investigate the happenings at ground level—life on the forest floor.

There certainly is more to a forest than the living trees. If you’re hiking through a grove of timber getting snared in a maze of prickly Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) and seeing little else but maybe a wild ungulate or two, then you’re in a has-been forest. Logging, firewood collection, fragmentation, and other man-made disturbances inside and near forests take a collective toll on their composition, eventually turning them to mere woodlots. Go enjoy the forests of the lower Susquehanna valley while you still can. And remember to do it gently; we’re losing quality as well as quantity right now—so tread softly.

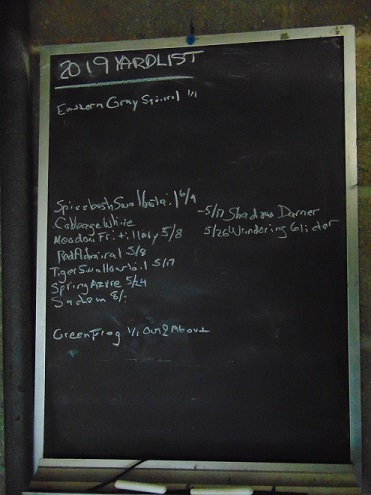

Clean Slate for 2020

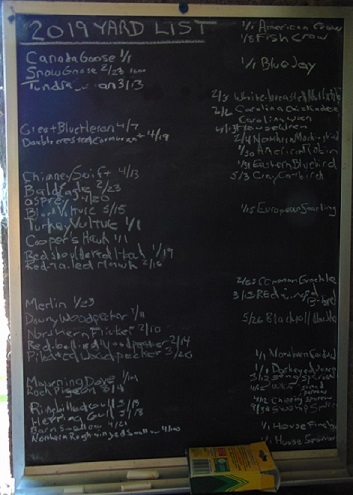

Inside the doorway that leads to your editor’s 3,500 square foot garden hangs a small chalkboard upon which he records the common names of the species of birds that are seen there—or from there—during the year. If he remembers to, he records the date when the species was first seen during that particular year. On New Year’s Day, the results from the freshly ended year are transcribed onto a sheet of notebook paper. On the reverse, the names of butterflies, mammals, and other animals that visited the garden are copied from a second chalkboard that hangs nearby. The piece of paper is then inserted into a folder to join those from previous New Year’s Days. The folder then gets placed back into the editor’s desk drawer beneath a circular saw blade and an old scratched up set of sunglasses—so that he knows exactly where to find it if he wishes to.

A quick glance at this year’s list calls to mind a few recollections.

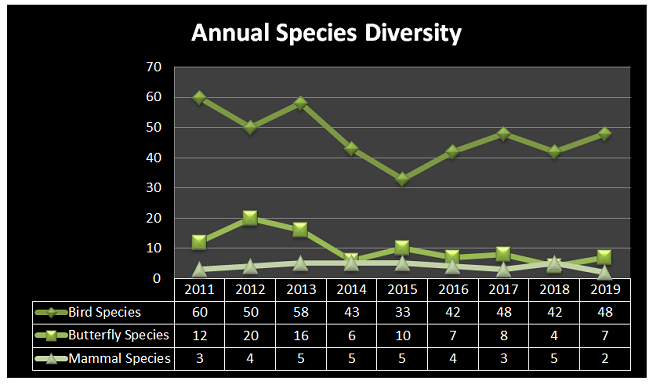

Before putting the folder back into the drawer for another year, the editor decided to count up the species totals on each of the sheets and load them into the chart maker in the computer.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

It appears that, at the very least, the garden habitat has been disconnected from the home ranges of many species by fragmentation. His little oasis is now isolated in a landscape that becomes increasingly hostile to native wildlife with each passing year. The paving of more parking areas, the elimination of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous growth from the large number of rental properties in the area, the alteration of the biology of the nearby stream by hand-fed domestic ducks, light pollution, and the outdoor use of pesticides have all contributed to the separation of the editor’s tiny sanctuary from the travel lanes and core habitats of many of the species that formerly visited, fed, or bred there. In 2019, migrants, particularly “fly-overs”, were nearly the only sightings aside from several woodpeckers, invasive House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and hardy Mourning Doves. Even rascally European Starlings became sporadic in occurrence—imagine that! It was the most lackluster year in memory.

If habitat fragmentation were the sole cause for the downward trend in numbers and species, it would be disappointing, but comprehendible. There would be no cause for greater alarm. It would be a matter of cause and effect. But the problem is more widespread.

Although the editor spent a great deal of time in the garden this year, he was also out and about, traveling hundreds of miles per week through lands on both the east and the west shores of the lower Susquehanna. And on each journey, the number of birds seen could be counted on fingers and toes. A decade earlier, there were thousands of birds in these same locations, particularly during the late summer.

In the lower Susquehanna valley, something has drastically reduced the population of birds during breeding season, post-breeding dispersal, and the staging period preceding autumn migration. In much of the region, their late-spring through summer absence was, in 2019, conspicuous. What happened to the tens of thousands of swallows that used to gather on wires along rural roads in August and September before moving south? The groups of dozens of Eastern Kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus) that did their fly-catching from perches in willows alongside meadows and shorelines—where are they?

Several studies published during the autumn of 2019 have documented and/or predicted losses in bird populations in the eastern half of the United States and elsewhere. These studies looked at data samples collected during recent decades to either arrive at conclusions or project future trends. They cite climate change, the feline infestation, and habitat loss/degradation among the factors contributing to alterations in range, migration, and overall numbers.

There’s not much need for analysis to determine if bird numbers have plummeted in certain Lower Susquehanna Watershed habitats during the aforementioned seasons—the birds are gone. None of these studies documented or forecast such an abrupt decline. Is there a mysterious cause for the loss of the valley’s birds? Did they die off? Is there a disease or chemical killing them or inhibiting their reproduction? Is it global warming? Is it Three Mile Island? Is it plastic straws, wind turbines, or vehicle traffic?

The answer might not be so cryptic. It might be right before our eyes. And we’ll explore it during 2020.

In the meantime, Uncle Ty and I going to the Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg. You should go too. They have lots of food there.

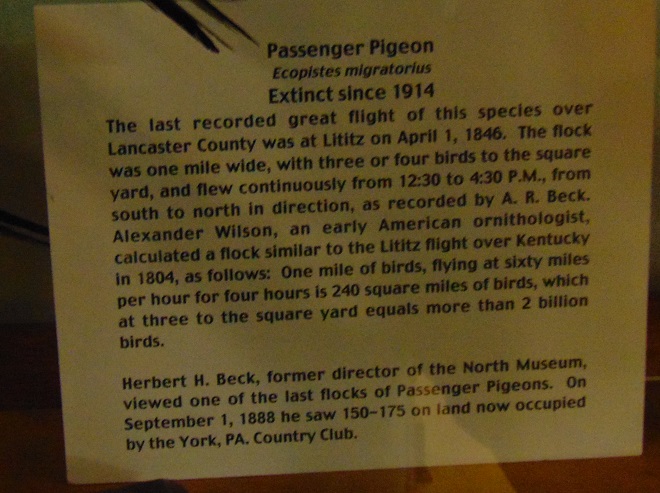

A Century of Extinction

Many are wont to say that they have no capacity for scientific pursuits, and having no capacity, they consequently have no love for them. I do not believe, that as a general thing, a love for science is necessarily innate in any man. It is the subject of cultivation and is therefore acquired. There are doubtless many, whose love for these and kindred pursuits is hereditary, through the mental biases and preoccupations of their progenitors, but in the masses of mankind it is quite otherwise. In this consists its redeeming qualities, for I do not think the truly scientific mind can either be an idle, a disorderly, or a very wicked one. There may be scientific men, who, forgetful of its teachings, are imperious and ambitious–who may have foregone their fealty to their country and their God, but as a general thing they are humble, social and law-abiding. If, therefore, there is a human being who desires to break off from old and evil associations, and form new and more virtuous ones, I would advise him to turn his attention to some scientific specialty, for the cultivation of a new affection, if there are no other and higher influences more accessible. In this pursuit he will, in time, be enabled to supplant the old and heartfelt affection. The occupation of his mind in the pursuit of scientific lore will wean him from vicious, trivial, and unmanly pursuits, and point out to him a way that is pleasant and instructive to walk in, which will ultimately lead to moral and intellectual usefulness. I wish I was accessible to them, and possessed the ability to impress this truth with sufficient emphasis upon the minds of the rising generation. This fact, that in all moral reformations, a love for the opposite of any besetting evil must be cultivated, before that evil can be surely eradicated, has been too much overlooked and too little valued in moral ethics. But true progress in this direction implies that, under all circumstances, men should “act in freedom according to reason.”

-Simon S. Rathvon