Solar Eclipse of 2024

It was dubbed the “Great Solar Eclipse”, the Great North American Eclipse”, and several other lofty names, but in the lower Susquehanna valley, where about 92% of totality was anticipated, the big show was nearly eclipsed by cloud cover. With last week’s rains raising the waters of the river and inundating the moonscape of the Pothole Rocks at Conewago Falls, we didn’t have the option of repeating our eclipse observations of August, 2017, by going there to view this year’s event, so we settled for the next best thing—setting up in the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters garden. So here it is, yesterday’s eclipse…

Prescribed Fire: Controlled Burns for Forest and Non-forest Habitats

Homo sapiens owes much of its success as a species to an acquired knowledge of how to make, control, and utilize fire. Using fire to convert the energy stored in combustible materials into light and heat has enabled humankind to expand its range throughout the globe. Indeed, humans in their furless incomplete mammalian state may have never been able to expand their populations outside of tropical latitudes without mastery of fire. It is fire that has enabled man to exploit more of the earth’s resources than any other species. From cooking otherwise unpalatable foods to powering the modern industrial society, fire has set man apart from the rest of the natural world.

In our modern civilizations, we generally look at the unplanned outbreak of fire as a catastrophe requiring our immediate intercession. A building fire, for example, is extinguished as quickly as possible to save lives and property. And fires detected in fields, brush, and woodlands are promptly controlled to prevent their exponential growth. But has fire gone to our heads? Do we have an anthropocentric view of fire? Aren’t there naturally occurring fires that are essential to the health of some of the world’s ecosystems? And to our own safety? Indeed there are. And many species and the ecosystems they inhabit rely on the periodic occurrence of fire to maintain their health and vigor.

Man has been availed of the direct benefits of fire for possibly 40,000 years or more. Here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the earliest humans arrived as early as 12,000 years ago—already possessing skills for using fire. Native plants and animals on the other hand, have been part of the ever-changing mix of ecosystems found here for a much longer period of time—millions to tens of millions of years. Many terrestrial native species are adapted to the periodic occurrence of fire. Some, in fact, require it. Most upland ecosystems need an occasional dose of fire, usually ignited by lightning (though volcanism and incoming cosmic projectiles are rare possibilities), to regenerate vegetation, release nutrients, and maintain certain non-climax habitat types.

But much of our region has been deprived of natural-type fires since the time of the clearcutting of the virgin forests during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This absence of a natural fire cycle has contributed to degradation and/or elimination of many forest and non-forest habitats. Without fire, a dangerous stockpile of combustible debris has been collecting, season after season, in some areas for a hundred years or more. Lacking periodic fires or sufficient moisture to sustain prompt decomposition of dead material, wildlands can accumulate enough leaf litter, thatch, dry brush, tinder, and fallen wood to fuel monumentally large forest fires—fires similar to those recently engulfing some areas of the American west. So elimination of natural fire isn’t just a problem for native plants and animals, its a potential problem for humans as well.

To address the habitat ailments caused by a lack of natural fires, federal, state, and local conservation agencies are adopting the practice of “prescribed fire” as a treatment to restore ecosystem health. A prescribed fire is a controlled burn specifically planned to correct one or more vegetative management problems on a given parcel of land. In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is used to…

-

-

- Eliminate dangerous accumulations of combustible fuels in woodlands.

- Reduce accumulations of dead plant material that may harbor disease.

- Provide top kill to promote oak regeneration.

- Regenerate other targeted species of trees, wildflowers, grasses, and vegetation.

- Kill non-native plants and promote growth of native plants.

- Prevent succession.

- Remove woody growth and thatch from grasslands.

- Promote fire tolerant species of plants and animals.

- Create, enhance, and/or manage specialized habitats.

- Improve habitat for rare species (Regal Fritillary, etc.)

- Recycle nutrients and minerals contained in dead plant material.

-

Let’s look at some examples of prescribed fire being implemented right here in our own neighborhood…

In Pennsylvania, state law provides landowners and crews conducting prescribed fire burns with reduced legal liability when the latter meet certain educational, planning, and operational requirements. This law may help encourage more widespread application of prescribed fire in the state’s forests and other ecosystems where essential periodic fire has been absent for so very long. Currently in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, prescribed fire is most frequently being employed by state agencies on state lands—in particular, the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources on State Forests and the Pennsylvania Game Commission on State Game Lands. Prescribed fire is also part of the vegetation management plan at Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation and on the land holdings of the Hershey Trust. Visitors to the nearby Gettysburg National Military Park will also notice prescribed fire being used to maintain the grassland restorations there.

For crews administering prescribed fire burns, late March and early April are a busy time. The relative humidity is often at its lowest level of the year, so the probability of ignition of previous years’ growth is generally at its best. We visited with a crew administering a prescribed fire at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area last week. Have a look…

Prescribed burns aren’t a cure-all for what ails a troubled forest or other ecosystem, but they can be an effective remedy for deficiencies caused by a lack of periodic episodes of naturally occurring fire. They are an important option for modern foresters, wildlife managers, and other conservationists.

If You’re Out Collecting Sweets, It Pays to Look Scary

Only fools mess around with bees, wasps, and hornets as they collect nectar and go about their business while visiting flowering plants. Relentlessly curious predators and other trouble makers quickly learn that patterns of white, yellow, or orange contrasting with black are a warning that the pain and anguish of being zapped with a venomous sting awaits those who throw caution to the wind. Through the process of natural selection, many venomous and poisonous animals have developed conspicuously bright or contrasting color schemes to deter would-be predators and molesters from making such a big mistake.

Visual warnings enhance the effectiveness of the defensive measures possessed by venomous, poisonous, and distasteful creatures. Aggressors learn to associate the presence of these color patterns with the experience of pain and discomfort. Thereafter, they keep their distance to avoid any trouble. In return, the potential victims of this unsolicited aggression escape injury and retain their defenses for use against yet-to-be-enlightened pursuers. Thanks to their threatening appearance, the chances of survival are increased for these would-be victims without the need to risk death or injury while deploying their venomous stingers, poisonous compounds, or other defensive measures.

One shouldn’t be surprised to learn that over time, as these aforementioned venomous, poisonous, and foul-tasting critters developed their patterns of warning colors, there were numerous harmless animals living within close association with these species that, through the process of natural selection, acquired nearly identical color patterns for their own protection from predators. This form of defensive impersonation is known as Batesian mimicry.

Let’s take a look at some examples of Batesian mimicry right here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Suppose for a moment that you were a fly. As you might expect, you would have plenty to fear while you spend your day visiting flowers in search of energy-rich nectar—hundreds of hungry birds and other animals want to eat you.

If you were a fly and you were headed out and about to call upon numerous nectar-producing flowers so you could round up some sweet treats, wouldn’t you feel a whole lot safer if you looked like those venomous bees, wasps, and hornets in your neighborhood? Wouldn’t it be a whole lot more fun to look scary—so scary that would-be aggressors fear that you might sting them if they gave you any trouble?

Suppose Mother Nature and Father Time dressed you up to look like a bee or a wasp instead of a helpless fly? Then maybe you could go out and collect sweets without always worrying about the bullies and the brutes, just like these flies of the lower Susquehanna do…

FLOWER FLIES/HOVER FLIES

TACHINID FLIES

BEE FLIES

So let’s review. If you’re a poor defenseless fly and you want to get your fair share of sweets without being gobbled up by the beasts, then you’ve got to masquerade like a strongly armed member of a social colony—like a bee, wasp, or hornet. Now look scary and go get your treats. HAPPY HALLOWEEN!

Hymanoptera: A Look at Some Bees, Wasps, Hornets, and Ants

What’s all this buzz about bees? And what’s a hymanopteran? Well, let’s see.

Hymanoptera—our bees, wasps, hornets and ants—are generally considered to be our most evolved insects. Some form complex social colonies. Others lead solitary lives. Many are essential pollinators of flowering plants, including cultivars that provide food for people around the world. There are those with stingers for disabling prey and defending themselves and their nests. And then there are those without stingers. The predatory species are frequently regarded to be the most significant biological controls of the insects that might otherwise become destructive pests. The vast majority of the Hymanoptera show no aggression toward humans, a demeanor that is seldom reciprocated.

Late summer and early autumn is a critical time for the Hymanoptera. Most species are at their peak of abundance during this time of year, but many of the adult insects face certain death with the coming of freezing weather. Those that will perish are busy, either individually or as members of a colony, creating shelter and gathering food to nourish the larvae that will repopulate the environs with a new generation of adults next year. Without abundant sources of protein and carbohydrates, these efforts can quickly fail. Protein is stored for use by the larval insects upon hatching from their eggs. Because the eggs are typically deposited in a cell directly upon the cache of protein, the larvae can begin feeding and growing immediately. To provide energy for collecting protein and nesting materials, and in some cases excavating nest chambers, Hymanoptera seek out sources of carbohydrates. Species that remain active during cold weather must store up enough of a carbohydrate reserve to make it through the winter. Honey Bees make honey for this purpose. As you are about to see, members of this suborder rely predominately upon pollen or insect prey for protein, and upon nectar and/or honeydew for carbohydrates.

We’ve assembled here a collection of images and some short commentary describing nearly two dozen kinds of Hymanoptera found in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the majority photographed as they busily collected provisions during recent weeks. Let’s see what some of these fascinating hymanopterans are up to…

SOLITARY WASPS

CUCKOO WASPS

SWEAT BEES

LEAFCUTTER AND MASON BEES

BUMBLE BEES, CARPENTER BEES, HONEY BEES, AND DIGGER BEES

SCOLIID WASPS

PAPER WASPS

YELLOWJACKETS AND HORNETS

POTTER WASPS

ANTS

We hope this brief but fascinating look at some of our more common bees, wasps, hornets, and ants has provided the reader with an appreciation for the complexity with which their food webs and ecology have developed over time. It should be no great mystery why bees and other insects, particularly native species, are becoming scarce or absent in areas of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where the landscape is paved, hyper-cultivated, sprayed, mowed, and devoid of native vegetation, particularly nectar-producing plants. Late-summer and autumn can be an especially difficult time for hymanopterans seeking the sources of proteins and carbohydrates needed to complete preparations for next year’s generations of these valuable insects. An absence of these staples during this critical time of year quickly diminishes the diversity of species and begins to tear at the fabric of the food web. This degradation of a regional ecosystem can have unforeseen impacts that become increasingly widespread and in many cases permanent.

Editor’s Note: No bees, wasp, hornets, or ants were harmed during this production. Neither was the editor swarmed, attacked, or stung. Remember, don’t panic, just observe.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

(If you’re interested in insects, get this book!)

Wild Senna, a Showy Background Plant for Your Wildflower Garden

Looking for a native wildflower that’s tall, showy, and a great choice for attracting wildlife, especially butterflies and bees? Then check out Wild Senna (Senna hebecarpa).

Wild Senna, also known as American Senna, is a host plant for the larvae of Cloudless Sulphur and Sleepy Orange (Eurema nicippe) butterflies. It thrives in almost any moist, well-drained soil in habitats including open woodlands, forest edges, meadows, and gardens like yours. Its height at flowering ranges from three to six feet. If you prefer, this perennial wildflower can even be cultivated as a shrub-like form. It is easily grown from seed, which is available from Ernst Conservation Seeds of Meadville, Pennsylvania, as well as numerous other vendors. And don’t forget to give Wild Senna’s two close relatives, Partridge Pea and Maryland Senna, a try as well. They attract the same species of butterflies and are just as easy to grow. You’ll like ’em.

A Few Plants with Wildlife Impact in June

Here’s a look at some native plants you can grow in your garden to really help wildlife in late spring and early summer.

The Value of Water

Are you worried about your well running dry this summer? Are you wondering if your public water supply is going to implement use restrictions in coming months? If we do suddenly enter a wet spell again, are you concerned about losing valuable rainfall to flooding? A sensible person should be curious about these issues, but here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, we tend to take for granted the water we use on a daily basis.

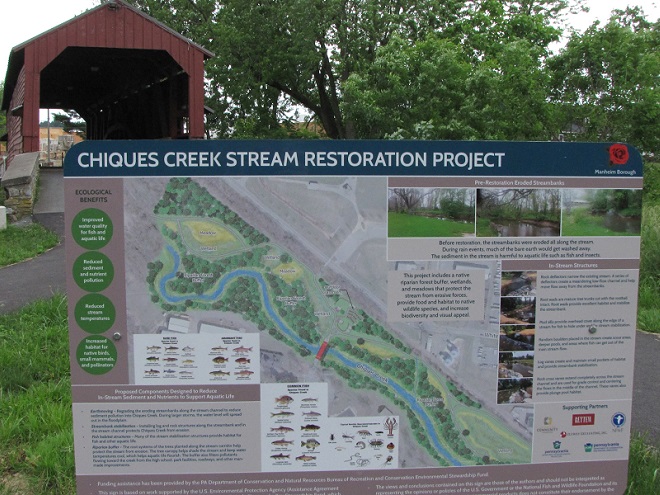

This Wednesday, June 7, you can learn more about the numerous measures we can take, both individually and as a community, to recharge our aquifers while at the same time improving water quality and wildlife habitat in and around our streams and rivers. From 5:30 to 8:00 P.M., the Chiques Creek Watershed Alliance will be hosting its annual Watershed Expo at the Manheim Farm Show grounds adjacent to the Manheim Central High School in Lancaster County. According to the organization’s web page, more than twenty organizations will be there with displays featuring conservation, aquatic wildlife, stream restoration, Honey Bees, and much more. There will be games and custom-made fish-print t-shirts for the youngsters, plus music to relax by for those a little older. Look for rain barrel painting and a rain barrel giveaway. And you’ll like this—admission and ice cream are free. Vendors including food trucks will be onsite preparing fare for sale.

And there’s much more.

To help recharge groundwater supplies, you can learn how to infiltrate stormwater from your downspouts, parking area, or driveway…

…there will be a tour of a comprehensive stream and floodplain rehabilitation project in Manheim Memorial Park adjacent to the fair grounds…

…and a highlight of the evening will be using an electrofishing apparatus to collect a sample of the fish now populating the rehabilitated segment of stream…

…so don’t miss it. We can hardly wait to see you there!

The 2023 Watershed Expo is part of Lancaster Conservancy Water Week.

Purple Haze Across the Fields

Have you noticed a purple haze across the fields right now? If so, you may have wondered, “What kind of flowers are they?”

Say hello to Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum), a non-native invasive species that has increased its prevalence in recent years by finding an improved niche in no-till cropland. Purple Dead Nettle, also known as Red Dead Nettle, is native to Asia and Europe. It has been a familiar early spring “weed” in gardens, along roadsides, and in other disturbed ground for decades.

Purple Dead Nettle owes its new-found success to the timing of its compressed growing season. Its tiny seeds germinate during the fall and winter, after crops have been harvested and herbicide application has ended for the season. The plants flower early in the spring and are thus particularly attractive to Honey Bees and other pollinators looking for a source of energy-rich nectar as they ramp up activity after winter lock down. In many cases, Purple Dead Nettle has already completed its flowering cycle and produced seeds before there is any activity in the field to prepare for planting the summer crop. The seeds spend the warmer months in dormancy, avoiding the hazards of modern cultivation that expel most other species of native and non-native plants from the agricultural landscape.

While modern farming has eliminated a majority of native plant and animal species from agricultural lands of the lower Susquehanna valley, its crop management practices have simultaneously invited vigorous invasion by a select few non-native species. High-intensity farming devotes its acreage to providing food for a growing population of people—not to providing wildlife habitat. That’s why it’s so important to minimize our impact on non-farm lands throughout the remainder of the watershed. If we continue subdividing, paving, and mowing more and more space, we’ll eventually be living in a polluted semi-arid landscape populated by little else but non-native invasive plants and animals. We can certainly do better than that.

Photo of the Day

Blooming in Early July: Great Rhododendron

With the gasoline and gunpowder gang’s biggest holiday of the year now upon us, wouldn’t it be nice to get away from the noise and the enduring adolescence for just a little while to see something spectacular that isn’t exploding or on fire? Well, here’s a suggestion: head for the hills to check out the flowers of our native rhododendron, the Great Rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum), also known as Rosebay.

Thickets composed of our native heathers/heaths (Ericaceae) including Great Rhododendron, Mountain Laurel, and Pinxter Flower (Rhododendron periclymenoides), particularly when growing in association with Eastern Hemlock and/or Eastern White Pine, provide critical winter shelter for forest wildlife. The flowers of native heathers/heaths attract bees and other pollinating insects and those of the deciduous Pinxter Flower, which blooms in May, are a favorite of butterflies and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

Forests with understories that include Great Rhododendrons do not respond well to logging. Although many Great Rhododendrons regenerate after cutting, the loss of consistent moisture levels in the soil due to the absence of a forest canopy during the sunny summertime can, over time, decimate an entire population of plants. In addition, few rhododendrons are produced by seed, even under optimal conditions. Great Rhododendron seeds and seedlings are very sensitive to the physical composition of forest substrate and its moisture content during both germination and growth. A lack of humus, the damp organic matter in soil, nullifies the chances of successful recolonization of a rhododendron understory by seed. In locations where moisture levels are adequate for their survival and regeneration after logging, impenetrable Great Rhododendron thickets will sometimes come to dominate a site. These monocultures can, at least in the short term, cause problems for foresters by interrupting the cycle of succession and excluding the reestablishment of native trees. In the case of forests harboring stands of Great Rhododendron, it can take a long time for a balanced ecological state to return following a disturbance as significant as logging.

In the lower Susquehanna region, the Great Rhododendron blooms from late June through the middle of July, much later than the ornamental rhododendrons and azaleas found in our gardens. Set against a backdrop of deep green foliage, the enormous clusters of white flowers are hard to miss.

In the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, there are but a few remaining stands of Great Rhododendron. One of the most extensive populations is in the Ridge and Valley Province on the north side of Second Mountain along Swatara Creek near Ravine (just off Interstate 81) in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. Smaller groves are found in the Piedmont Province in the resort town of Mount Gretna in Lebanon County and in stream ravines along the lower river gorge at the Lancaster Conservancy’s Ferncliff and Wissler’s Run Preserves. Go have a look. You’ll be glad you did.

Some Autumn Insects

With autumn coming to a close, let’s have a look at some of the fascinating insects (and a spider) that put on a show during some mild afternoons in the late months of 2019.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

Noxious Benefactor

It’s sprayed with herbicides. It’s mowed and mangled. It’s ground to shreds with noisy weed-trimmers. It’s scorned and maligned. It’s been targeted for elimination by some governments because it’s undesirable and “noxious”. And it has that four letter word in its name which dooms the fate of any plant that possesses it. It’s the Common Milkweed, and it’s the center of activity in our garden at this time of year. Yep, we said milk-WEED.

Now, you need to understand that our garden is small—less than 2,500 square feet. There is no lawn, and there will be no lawn. We’ll have nothing to do with the lawn nonsense. Those of you who know us, know that the lawn, or anything that looks like lawn, are through.

Anyway, most of the plants in the garden are native species. There are trees, numerous shrubs, some water features with aquatic plants, and filling the sunny margins is a mix of native grassland plants including Common Milkweed. The unusually wet growing season in 2018 has been very kind to these plants. They are still very green and lush. And the animals that rely on them are having a banner year. Have a look…

We’ve planted a variety of native grassland species to help support the milkweed structurally and to provide a more complete habitat for Monarch butterflies and other native insects. This year, these plants are exceptionally colorful for late-August due to the abundance of rain. The warm season grasses shown below are the four primary species found in the American tall-grass prairies and elsewhere.

There was Monarch activity in the garden today like we’ve never seen before—and it revolved around milkweed and the companion plants.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.