It’s a hot summer weekend with a sun so bright that creosote is dripping from utility poles onto the sidewalks. Dodging these sticky little puddles of tar can cause one to reminisce about sultry days-gone-by.

Sometime in July or August each year, about half a century ago, we would cram all the gear for seven days of living into the car and head for the beaches of Delmarva or New Jersey. It was family vacation time, that one week a year when the working class fantasizes that they don’t have it so bad during the other fifty-one weeks of the year.

The trip to the coast from the Susquehanna valley was a day-long journey. Back then, four-lane highways were few beyond the cities of the northeast corridor and traffic jams stretched for miles. Cars frequently overheated and steam rolled from beneath the hoods of those stopped to cool down. There were even 55-gallon drums of non-potable water positioned at known choke points along some of the state roads so that motorists could top off their radiators and proceed on. Within these back-ups there were many Volkswagen Beetles pausing along the side of the road with the rear hood propped up. Their air-cooled engines would overheat on a hot day if the car wasn’t kept moving. But, despite the setbacks, all were motivated to continue. In time, with perseverance, the smell of saltmarsh air was soon rolling in the windows. Our destination was near.

At the shore, priority one was to spend plenty of time at the beach. Sunbathers lathered up with various concoctions of oils and moisturizers, including my personal favorite, cocoa butter, then they broiled themselves in the raging rays of the fusion-reaction furnace located just eight light-minutes away. Reflected from the white sand and ocean surf, the flaming orb’s blinding light did a thorough job of cooking all the thousands of oil-basted sun worshippers packing the tidal zone for miles and miles. You could smell the hot cocoa butter in the summer air as they burned. Well, maybe not, but you could smell something there.

By now, you’re probably saying, “Hey, why weren’t you idiots wearing protection from the sun’s harmful U.V. rays?”

Good question. Uncle Tyler Dyer reminds me that back in the sixties, a sunscreen was a shade hung to cover a window. He continued, “Man, the only sun block we had was a beach ball that happened to pass between us and the sun.”

During several of our summertime beach visits in the early 1970s, we got a different sort of oil treatment—tar balls. We never noticed the things until we got out of the water. Playing around at the tide line and taking a tumble in the surf from time to time, we must have picked them up when we rolled in the sand.

Uncle Ty wasn’t happy, “Man, they’re sticking all over our legs and feet, and look at your swim trunks, they’re ruined. And look in the sand, they’re everywhere.” The event was one of the seeds that would in time grow into Uncle Ty’s fundamental distrust of corporate culture.

Looking around, tar balls were all over everyone who happened to be near the water. Rumor on the beach was that they came from ships that passed by offshore earlier in the day. The probable source was the many oil spills that had occurred in the Mid-Atlantic region in those years. During the first six months of 1973 alone, there were over 800 oil spills there. Three hundred of those spills occurred in the waters surrounding New York City. The largest, almost half a million gallons, occurred in New York Harbor when a cargo ship collided with the tanker “Esso Brussels”. Forty percent of that spill burned in the fire that followed the mishap, the remainder entered the environment.

When it was time to clean up, we slowly removed the tar from our legs and feet by rubbing it away with a rag soaked in charcoal lighter fluid or gasoline. Needless to say, our skin turned redder than it had already been from sunburn.

After a full day in the surf, we’d be on our way back to our “home base” for summer vacation, a campground nestled somewhere in the pines on the mainland side of the tidal marshes behind our beach’s barrier island. There, we’d shake the sand out of our trunks and savor the feeling of dry clothing. As the sun set, the smoke, flicker, and crackle of dozens of campfires filled the spaces between the tents and camping trailers. Colored lights strung around awnings dazzled sun-weary eyes as night descended across the landscape. We’d commence the process of incinerating some marshmallows soon after. Then, sometime while we were roasting our weenies and warming our buns, we’d hear it.

His device didn’t have a very good muffler. It sounded like a rusty old lawn mower running on the back of a rusty old truck that didn’t sound much better. And you could see the cloud rising above the campsites around the corner as he approached. It was the mosquito man, come to rid the place of pesky nocturnal biting insects. Behind him, always, were young boys on bicycles riding in and out of the fog of insecticide that rolled from the back of the truck.

One was wise to quickly eat your campfire food and put the rest away before the fog rolled in. You had just minutes to choke down that burned up hot dog. Then the sense of urgency was gone. Everyone just sat around at picnic tables and on lawn chairs bathing in the airborne cloud. A thin layer of insecticide rubbed into the skin along with the liberal doses of Noxzema being applied to soothe sunburn pain will get you through the night just fine.

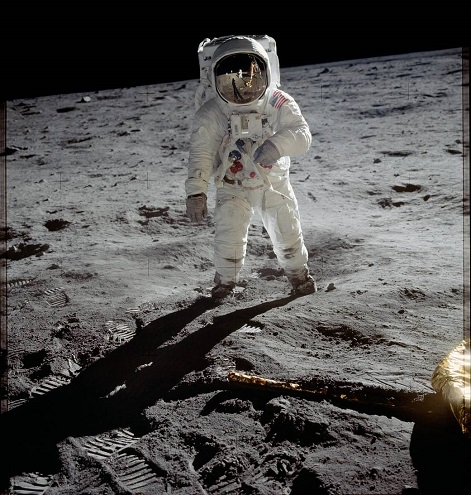

Perhaps the most memorable event to occur during our summer vacations happened at the moment of this writing, fifty years ago.

We were vacationing in a campground in southern New Jersey. Our family and the family of my dad’s co-worker gathered in a mosquito-mesh tent surrounding a small black-and-white television. An extension cord was strung to a receptacle on a nearby post, and the cathode ray tube produced the familiar picture of glowing blue tones to illuminate the otherwise dark scene. There was constant experimentation with the whip antenna to try to get a visible signal. There were no local UHF broadcasters and the closest VHF television stations were in Philadelphia, so the picture constantly had “snow” diminishing its already poor clarity. But we could see it, and I’ll never forget it.

SOURCES

Andelman, David A. “Oil Spills Here Total 300 in ’73”. The New York Times. August 8, 1973. p.41.

Cortright, Edgar M. (Editor). 1975. Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, DC.