Within the last few years, the early-summer emergence of vast waves of mayflies has caused great consternation among residents of riverside towns and motorists who cross the bridges over the lower Susquehanna. Fishermen and others who frequent the river are familiar with the phenomenon. Mayflies rise from their benthic environs where they live for a year or more as an aquatic larval stage (nymph) to take flight as a short-lived adult (imago), having just one night to complete the business of mating before perishing by the following afternoon.

In 2015, an emergence on a massive scale prompted the temporary closure of the mile-long Columbia-Wrightsville bridge while a blizzard-like flight of huge mayflies reduced visibility and caused road conditions to deteriorate to the point of causing accidents. The slimy smelly bodies of dead mayflies, probably millions of them, were removed like snow from the normally busy Lincoln Highway. Since then, to prevent attraction of the breeding insects, lights on the bridge have been shut down from about mid-June through mid-July to cover the ten to fourteen day peak of the flight period of Hexagenia bilineata, sometimes known as the Great Brown Drake, the species that swarms the bridge.

After so many years, why did the swarms of these mayflies suddenly produce the enormous concentrations seen on this particular bridge across the lower Susquehanna? Let’s have a look.

Following the 2015 flight, conservation organizations were quick to point out that the enormous numbers of mayflies were a positive thing—an indicator that the waters of the river were getting cleaner. Generally, assessments of aquatic invertebrate populations are considered to be among the more reliable gauges of stream health. But some caution is in order in this case.

Prior to the occurrence of large flights several years ago, Hexagenia bilineata was not well known among the species in the mayfly communities of the lower Susquehanna and its tributaries. The native range of the species includes the southeastern United States and the Mississippi River watershed. Along segments of the Mississippi, swarms such as occurred at Columbia-Wrightsville in 2015 are an annual event, sometimes showing up on local weather radar images. These flights have been determined to be heaviest along sections of the river with muddy bottoms—the favored habitat of the burrowing Hexagenia bilineata nymph. This preferred substrate can be found widely in the Susquehanna due to siltation, particularly behind dams, and is the exclusive bottom habitat in Lake Clarke just downstream of the Columbia-Wrightsville bridge.

Native mayflies in the Susquehanna and its tributaries generally favor clean water in cobble-bottomed streams. Hexagenia bilineata, on the other hand, appears to have colonized the river (presumably by air) and has found a niche in segments with accumulated silt, the benthic habitats too impaired to support the native taxa formerly found there. Large flights of burrowing mayflies do indicate that the substrate didn’t become severely polluted or eutrophic during the preceding year. And big flights tell us that the Susquehanna ecosystem is, at least in areas with silt bottoms, favorable for colonization by the Great Brown Drake. But large flights of Hexagenia bilineata mayflies don’t necessarily give us an indication of how well the Susquehanna ecosystem is supporting indigenous mayflies and other species of native aquatic life. Only sustained recoveries by populations of the actual native species can tell us that. So, it’s probably prudent to hold off on the celebrations. We’re a long way from cleaning up this river.

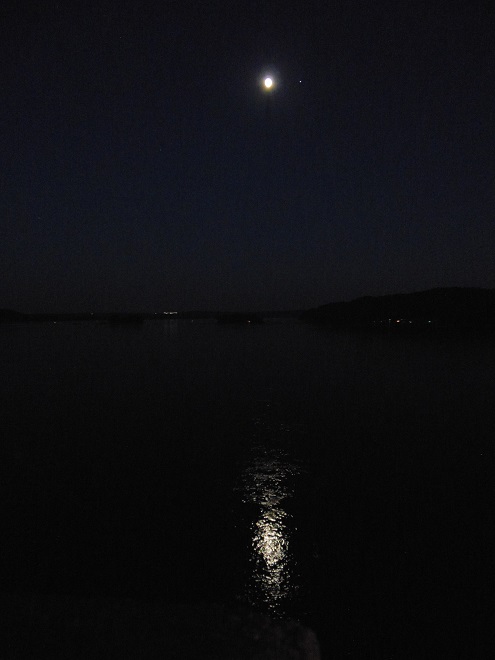

In the absence of man-made lighting, male Great Brown Drakes congregate over waterways lit often by moonlight alone. The males hover in position within a swarm, often downwind of an object in the water. As females begin flight and pass through the swarm, they are pursued by the males in the vicinity. The male response is apparently sight motivated—anything moving through their field of view in a straight line will trigger a pursuit. That’s why they’re so pesky, landing on your face whenever you approach them. Mating takes place as males rendezvous with airborne females. The female then drops to the water surface to deposit eggs and later die—if not eaten by a fish first. Males return to the swarm and may mate again and again. They die by the following afternoon. After hatching, the larvae (nymphs) burrow in the silt where they’ll grow for the coming year. Feathery gills allow them to absorb oxygen from water passing through the U-shaped refuge they’ve excavated.

Several factors increase the likelihood of large swarms of Great Brown Drakes at bridges. Location is, of course, a primary factor. Bridges spanning suitable habitat will, as a minimum, experience incidental occurrences of the flying forms of the mayflies that live in the waters below. Any extraordinarily large emergence will certainly envelop the bridge in mayflies. Lights, both fixed and those on motor vehicles, enhance the appearance of movement on a bridge deck, thus attracting hovering swarms of male Hexagenia bilineata and other species from a greater distance, leading to larger concentrations. Concrete walls along the road atop the bridge lure the males to try to hover in a position of refuge behind them, despite the vehicles that disturb the still air each time they pass. The walls also function as the ultimate visual attraction as headlamp beams and shadows cast by moving vehicles are projected onto them over the length of the bridge. Vast numbers of dead, dying, and maimed mayflies tend to accumulate along these walls for this reason.

The absence of illumination from fixed lighting on the deck of the bridge reduces the density of Great Brown Drake swarms. Some communities take mayfly countermeasures one step further. Along the Mississippi, some bridges are fitted with lights on the underside of the deck to attract the mayflies to the area directly over the water, concentrating the breeding mayflies and fishermen alike. The illumination below the bridge is intended to draw mayflies away from light created by headlamps on motor vehicles passing by on the otherwise dark deck above. Lights beneath the bridge also help prevent large numbers of mayflies from being drawn away from the water toward lights around businesses and homes in neighborhoods along the shoreline—where they can become a nuisance.

SOURCES

Edsall, Thomas A. 2001. “Burrowing Mayflies (Hexagenia) as Indicators of Ecosystem Health.” Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management. 43:283-292.

Fremling, Calvin R. 1960. Biology of a Large Mayfly, Hexagenia bilineata (Say), of the Upper Mississippi River. Research Bulletin 482. Agricultural and Home Economics Experiment Station, Iowa State University. Ames, Iowa.

McCafferty, W. P. 1994. “Distributional and Classificatory Supplement to the Burrowing Mayflies (Ephemeroptera: Ephimeroidea) of the United States.” Entomological News. 105:1-13.