Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY SEVEN—May 27, 1983

“Bentsen State Park”

“6 A.M. alarm rang. After breakfast we walked an hour or more. At 8:15 we phoned Father Tom for more information. We next went back to Anzalduas County Park in hopes of seeing a Hook-billed Kite. It is now 11:30 and NO luck. Steve got his first lifer — Red-billed Pigeon. We parked on a dirt dike and they went walking. I took a nap.”

Based on new tips from Father Tom, we had back-tracked east along the Rio Grande to look for Hook-billed Kite, Red-billed Pigeon (Patagioenas flavirostris), and other species before continuing west toward Falcon Dam in coming days. The pigeon was yet another specialty with a range that extends north from Central America into the subtropical riparian forests of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

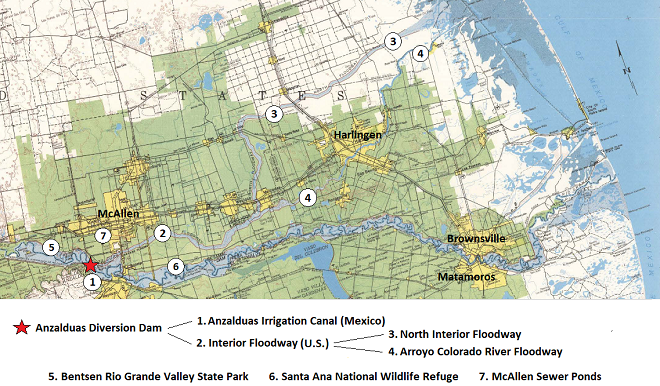

Anzalduas County Park is located along the Rio Grande at the Anzalduas Diversion Dam, part of a network of flood control projects initiated in the 1930s to reign in the “untamed river”. Construction on this particular dam began in 1956 and was completed in 1960. Operation of diversion and flood control dams on the Rio Grande has functionally eliminated stream meander along its present course, thus the delta that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley will cease to experience the morphological changes that create wetlands, resacas, and other natural features in the floodplain. Thought to be excellent ideas at the time, most of these projects were based on a blurred vision of the connection between streams, their floodplains, and the watershed’s aquifer. This condition has manifested itself as a blindness to the finite nature of water supplies, particular where consumption rates are still sharply rising while groundwater recharge is diminishing.

In addition to the Red-billed Pigeon, we found Brown-headed Cowbirds at Anzalduas County Park. Flying over the adjacent reservoir/river there were Caspian Terns. We identified some turtles too—Red-eared Sliders.

“After my nap, I took pictures of the place and of the men coming back. Then to the McAllen Sewage Ponds where we had some luck — Eared Grebe and others.”

The McAllen Sewage Ponds were like a little oasis for waterbirds. Though not a specialty of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the Eared Grebe (Podiceps nigricollis) was a western species we were happy to have seen. A Gulf Coast species, Mottled Duck (Anas fulvigula), was another welcome find. Other sightings included Least Grebe, 100 Ruddy Ducks, Northern Shoveler, Mallard, Black-bellied Whistling Duck, American Coot, Common Gallinule, Spotted Sandpiper, White-faced Ibis (Plegadis chihi), Black-necked Stilt, Franklin’s Gull, Least Tern (Sternula antillarum), Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Great-tailed Grackle, and Bronzed Cowbird.

Swimming around in the McAllen Sewage Ponds was a Nutria (Myocastor coypus), also known as the Coypu, a mammal resembling a giant muskrat—remember, things really are bigger in Texas.

“Next to the Time Out Camp Ground to check with a couple I met in February. They had moved, their space was empty. Back to Bentsen State Park. On the way we bought a watermelon for supper’s dessert. Rain almost all P.M. Raining now 8:00 P.M. Before supper we checked again for the Tropical Parula with no luck. The watermelon was very good for dessert.”

Details received this morning from Father Tom suggested we check the area of the Bentsen Rio Grande Valley State Park campground near a large Spanish Moss-draped tree for the nesting Tropical Parulas. I don’t recall what kind of tree it was, but the paved road circled the area surrounding it indicating that those who had designed the campground had purposely preserved this massive specimen as something unique. Despite its prominence, no sights or sounds of the Tropical Parulas were found. We reached the conclusion that we were a little late; they were gone for the year. To soothe our sorrows, we ate watermelon—very refreshing!