Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Tropical Storm Ophelia has put the brakes on a bustling southbound exodus of the season’s final waves of Neotropical migrants. Winds from easterly directions have now beset the Mid-Atlantic States with gloomy skies, chilly temperatures, and periods of rain for an entire week. These conditions, which are less than favorable for undertaking flights of any significant distance, have compelled many birds to remain in place—grounded to conserve energy.

Of the birds on layover, perhaps the most interesting find has been a western raptor that occurs only on rare occasions among the groups of Broad-winged Hawks seen at hawk watches each fall—a Swainson’s Hawk. Discovered as Tropical Storm Ophelia approached on September 21st, this juvenile bird has found refuge in coal country on a small farm in a picturesque valley between converging ridges in southern Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. Swainson’s Hawks are a gregarious species, often spending time outside of the nesting season in the company of others of their kind. Like Broad-winged Hawks, they frequently assemble into large groups while migrating.

Swainson’s Hawks nest in the grasslands, prairies, and deserts of western North America. Their autumn migration to wintering grounds in Argentina covers a distance of up to 6,000 miles. Among raptors, such mileage is outdone only by the Tundra Peregrine Falcon.

During the nesting cycle, Swainson’s Hawks consume primarily small vertebrates, mostly mice and other small rodents. But during the remainder of the year, they feed almost exclusively on grasshoppers. To provide enough energy to fuel their migrations, they must find and devour these insects by the hundreds. Not surprisingly, the Swainson’s Hawk is sometimes known as the Grasshopper Hawk or Locust Hawk, particularly in the areas of South America where they are common.

So just how far will our wayward Swainson’s Hawk have to travel to get back on track? Small numbers of Swainson’s Hawks pass the winter in southern Florida each year and still others are found in and near the scrublands of the Lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas and Mexico. But the vast majority of these birds make the trip all the way to the southern half of South America and the farmlands and savannas of Argentina—where our winter is their summer. The best bet for this bird would be to get hooked up with some of the season’s last Broad-winged Hawks when they start flying in coming days, then join them as they head toward Houston, Texas, to make the southward turn down the coast of the Gulf of Mexico into Central America and Amazonia. Then again, it may need to find its own way to warmer climes. Upon reaching at least the Gulf Coastal Plain, our visitor stands a much better chance of surviving the winter.

Grasshoppers are perhaps best known for the occasions throughout history when an enormous congregation of these insects—a “plague of locusts”—would assemble and rove a region to feed. These swarms, which sometimes covered tens of thousands of square miles or more, often decimated crops, darkened the sky, and, on occasion, resulted in catastrophic famine among human settlements in various parts of the world.

The largest “plague of locusts” in the United States occurred during the mid-1870s in the Great Plains. The Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus), a grasshopper of prairies in the American west, had a range that extended east into New England, possibly settling there on lands cleared for farming. Rocky Mountain Locusts, aside from their native habitat on grasslands, apparently thrived on fields planted with warm-season crops. Like most grasshoppers, they fed and developed most vigorously during periods of dry, hot weather. With plenty of vegetative matter to consume during periods of scorching temperatures, the stage was set for populations of these insects to explode in agricultural areas, then take wing in search of more forage. Plagues struck parts of northern New England as early as the mid-1700s and were numerous in various states in the Great Plains through the middle of the 1800s. The big ones hit between 1873 and 1877 when swarms numbering as many as trillions of grasshoppers did $200 million in crop damage and caused a famine so severe that many farmers abandoned the westward migration. To prevent recurrent outbreaks of locust plagues and famine, experts suggested planting more cool-season grains like winter wheat, a crop which could mature and be harvested before the grasshoppers had a chance to cause any significant damage. In the years that followed, and as prairies gave way to the expansive agricultural lands that presently cover most of the Rocky Mountain Locust’s former range, the grasshopper began to disappear. By the early years of the twentieth century, the species was extinct. No one was quite certain why, and the precise cause is still a topic of debate to this day. Conversion of nearly all of its native habitat to cropland and grazing acreage seems to be the most likely culprit.

In the Mid-Atlantic States, the mosaic of the landscape—farmland interspersed with a mix of forest and disturbed urban/suburban lots—prevents grasshoppers from reaching the densities from which swarms arise. In the years since the implementation of “Green Revolution” farming practices, numbers of grasshoppers in our region have declined. Systemic insecticides including neonicotinoids keep grasshoppers and other insects from munching on warm-season crops like corn and soybeans. And herbicides including 2,4-D (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) have, in effect, become the equivalent of insecticides, eliminating broadleaf food plants from the pasturelands and hayfields where grasshoppers once fed and reproduced in abundance. As a result, few of the approximately three dozen species of grasshoppers with ranges that include the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are common here. Those that still thrive are largely adapted to roadsides, waste ground, and small clearings where native and some non-native plants make up their diet.

Here’s a look at four species of grasshoppers you’re likely to find in disturbed habitats throughout our region. Each remains common in relatively pesticide-free spaces with stands of dense grasses and broadleaf plants nearby.

CAROLINA GRASSHOPPER

Dissosteira carolina

DIFFERENTIAL GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus differentialis

TWO-STRIPED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus bivittatus

RED-LEGGED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus femurrubrum

Protein-rich grasshoppers are an important late-summer, early-fall food source for birds. The absence of these insects has forced many species of breeding birds to abandon farmland or, in some cases, disappear altogether.

During the past two weeks, over 150 American Flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) have been reported in the eastern half of the United States, well north of their usual range—northern South America; Cuba, the Bahamas, and other Caribbean Islands; and the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. They are also found on the Galapagos Islands. Prior to being extirpated by hunting during the early years of the twentieth century, American Flamingos nested in the Everglades of Florida as well.

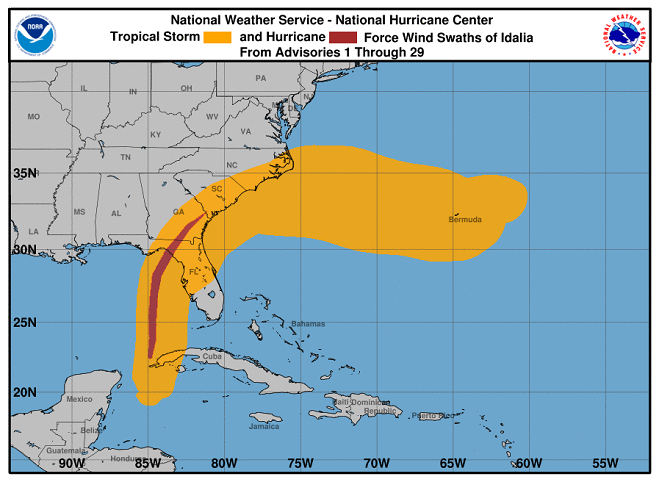

The recent influx of these tropical vagrants into the eastern states is attributed to Hurricane Idalia, a storm that formed in the midst of flamingo territory during the final week of August. Idalia got its start over tropical waters off Yucatan before progressing north through the Gulf of Mexico off Cuba to make landfall in the “Big Bend” area of Florida.

Birds of warm water seas regularly become entangled within tropical storms and hurricanes. In most cases, it’s oceanic seabirds including petrels, shearwaters, terns, and gulls that seek refuge from turbulent conditions by remaining inside the storm’s eye or within the margins of the rotating bands. The duration of the experience and the fitness of each individual bird may determine just how many survive such an ordeal. As a storm makes landfall, the survivors put down on inland bodies of water, often in unexpected places hundreds of miles from the nearest coastline. Some may linger in these far-flung areas to feed and gain strength before finding their way down rivers back to sea.

For birds like American Flamingos, which don’t spend a large portion of their lives on the wing over vast oceanic waters, becoming entangled in a tropical weather system can easily be a life-ending event. American Flamingos, despite their size and lanky appearance, are quite agile fliers. When necessary, some populations travel significant distances in search of new food sources. Some closely related migratory species of flamingos have been recorded at altitudes exceeding 10,000 feet. But becoming trapped in a hurricane for an extended period of time could easily erode the endurance of even the strongest of fliers. And once out over open water, there’s nowhere for a flamingo to come down for a rest.

It appears probable that, during the final week of August, hundreds of American Flamingos did find themselves drawn away from their familiar tidal flats and salty lagoons to be swept into the spinning clouds and gusty downpours of Hurricane Idalia as it churned off the Yucatan coast. Despite the dangers, more than 150 of them completed a journey within its clutches to cross the Gulf of Mexico and land in the Eastern United States.

Amy Davis in a report for the American Birding Association compiled a list of American Flamingo sightings from the days following the landfall of Hurricane Idalia. We’ve plotted those sightings on a satellite image of the storm.

The majority of the flamingos that survived this harrowing trip found a place to put down along the coast. But as the reader will notice, a significant number of the sightings were outside the path of the storm in areas not reached by even the outermost bands of clouds. Flamingos in Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky/Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania were found at inland bodies of water, most on the days immediately following the storm’s landfall. The lone exception, the Pennsylvania birds, were discovered a week after landfall (but may have been there days longer). How and why did these birds find their way so far inland at places so distant from the storm…and home? And how did they get there so quickly? The counterclockwise rotation of the hurricane wouldn’t slingshot them in that direction, would it?

Let’s have a look at the surface map showing us the weather in the states outside the direct influence of Hurricane Idalia during the storm’s landfall on August 30, 2023…

Now check out this satellite view of the storm during the hours following landfall…

Click the image above to play a GIF animation of GOES-16 satellite photos showing Idalia after landfall and the strong “flamingo highway” winds between the fronts. (It’s a big file, so give it a little time to load.) You’ll also note the ferocious lightning associated with both Huricane Idalia and Hurricane Franklin.

Did the inland flamingos catch a ride on these stiff “flamingo highway” winds? If not, they may have had a little help from a high pressure ridge that became established over the southern Appalachians as Idalia crept out to sea. The clockwise rotation of this ridge kept a similar flow over the “flamingo highway” for much of the four days that followed.

For vagrant birds including those carried away to distant lands by hurricanes and other storms, the challenges of finding food and avoiding hazards including disease, unfamiliar predators, and extreme weather can be a matter of life and death. For American Flamingos now loafing and feeding in the Eastern United States outside Florida, the hardest part of their journey is yet to come. They need to find their way back south to suitable tropical habitat before cold weather sets in. The perils are many. Theirs is not an enviable predicament.

To pass the afternoon, we sat quietly along the edge of a pond created recently by North American Beavers (Castor canadensis). They first constructed their dam on this small stream about five years ago. Since then, a flourishing wetland has become established. Have a look.

Isn’t that amazing? North American Beavers build and maintain what human engineers struggle to master—dams and ponds that reduce pollution, allow fish passage, and support self-sustaining ecosystems. Want to clean up the streams and floodplains of your local watershed? Let the beavers do the job!

“Waves” of warblers and other Neotropical songbirds continue to roll along the ridgetops of southern Pennsylvania. The majority of these migrants are headed to wintering habitat in the tropics after departing breeding grounds in the forests of southern Canada. At Second Mountain Hawk Watch, today’s early morning flight kicked off at sunrise, then slowed considerably by 8:30 A.M. E.D.T. Once again, in excess of 400 warblers were found moving through the trees and working their way southwest along the spine of the ridge. Each of the 12 species seen yesterday were observed today as well. In addition, there was a Northern Parula and a Canada Warbler. Today’s flight was dominated by Bay-breasted, Blackburnian, Black-throated Green, and Tennessee Warblers.

Other interesting Neotropical migrants joined the “waves” of warblers…

During the recent couple of mornings, a tide of Neotropical migrants has been rolling along the crests of the Appalachian ridges and Piedmont highlands of southern Pennsylvania. In the first hours of daylight, “waves” of warblers, vireos, flycatchers, tanagers, and other birds are being observed flitting among the sun-drenched foliage as they feed in trees along the edges of ridgetop clearings. Big fallouts have been reported along Kittattiny Ridge/Blue Mountain at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and at Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch. Birds are also being seen in the Furnace Hills of the Piedmont.

Here are some of the 300 to 400 warblers (a very conservative estimate) seen in a “wave” found working its way southwest through the forest clearing at the Second Mountain Hawk Watch in Lebanon County this morning. The feeding frenzy endured for two hours between 7 and 9 A.M. E.D.T.

Not photographed but observed in the mix of species were several Black-throated Blue Warblers and American Redstarts.

In addition to the warblers, other Neotropical migrants were on the move including two Common Nighthawks, a Broad-winged Hawk, a Least Flycatcher (Empidonax minimus), and…

Then, there was a taste of things to come…

Seeing a “wave” flight is a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Visiting known locations for observing warbler fallouts such as hawk watches, ridgetop clearings, and peninsular shorelines can improve your chances of witnessing one of these memorable spectacles by overcoming the first variable. To overcome the second, be sure to visit early and often. See you on the lookout!

As we enter September, autumn bird migration is well underway. Neotropical species including warblers, vireos, flycatchers, and nighthawks are already headed south. Meanwhile, the raptor migration is ramping up and hawk watch sites throughout the Mid-Atlantic States are now staffed and counting birds. In addition to the expected migrants, there have already been sightings of some unusual post-breeding wanderers. Yesterday, a Wood Stork (Mycteria americana) was seen passing Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and a Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus) that spent much of August in Juniata County was seen from Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch while it was hunting in a Perry County field six miles to the north of the lookout! Both of these rarities are vagrants from down Florida way.

To plan a visit to a hawk watch near you, click on the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page to find a list and brief description of suggested sites throughout the Mid-Atlantic region. “Hawkwatcher’s Helper” also includes an extensive photo guide for identifying the raptors you’re likely to see.

And to identify those confusing fall warblers and other migrants, click the “Birds” tab at the top of this page and check out the photo guide contained therein. It includes nearly all of the species you’re likely to see in the lower Susquehanna valley.

At Lake Redman just to the south of York, Pennsylvania, a draw down to provide drinking water to the city while maintenance is being performed on the dam at neighboring Lake Williams, York’s primary water source, has fortuitously coincided with autumn shorebird migration. Here’s a sample of the numerous sandpipers and plovers seen today on the mudflats that have been exposed at the southeast end of the lake…

Not photographed but present at Lake Redman were at least two additional species of shorebirds, Killdeer and Spotted Sandpiper—bringing the day’s tally to ten. Not bad for an inland location! It’s clearly evident that these waders overfly the lower Susquehanna valley in great numbers during migration and are in urgent need of undisturbed habitat for making stopovers to feed and rest so that they might improve their chances of surviving the long journey ahead of them. Mud is indeed a much needed refuge.

Looking for a native wildflower that’s tall, showy, and a great choice for attracting wildlife, especially butterflies and bees? Then check out Wild Senna (Senna hebecarpa).

Wild Senna, also known as American Senna, is a host plant for the larvae of Cloudless Sulphur and Sleepy Orange (Eurema nicippe) butterflies. It thrives in almost any moist, well-drained soil in habitats including open woodlands, forest edges, meadows, and gardens like yours. Its height at flowering ranges from three to six feet. If you prefer, this perennial wildflower can even be cultivated as a shrub-like form. It is easily grown from seed, which is available from Ernst Conservation Seeds of Meadville, Pennsylvania, as well as numerous other vendors. And don’t forget to give Wild Senna’s two close relatives, Partridge Pea and Maryland Senna, a try as well. They attract the same species of butterflies and are just as easy to grow. You’ll like ’em.

Your best bet for finding migrating shorebirds in the lower Susquehanna region is certainly a visit to a sandbar or mudflat in the river. The Conejohela Flats off Washington Boro just south of Columbia is a renowned location. Some man-made lakes including the one at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area are purposely drawn down during the weeks of fall migration to provide exposed mud and silt for feeding and resting sandpipers and plovers. But with the Susquehanna running high due to recent rains and the cost of fuel trending high as well, maybe you want to stay closer to home to do your observing.

Fortunately for us, migratory shorebirds will drop in on almost any biologically active pool of shallow water and mud that they happen to find. This includes flooded portions of fields, construction sites, and especially stormwater retention basins. We stopped by a new basin just west of Hershey, Pennsylvania, and found more than two dozen shorebirds feeding and loafing there. We took each of these photographs from the sidewalk paralleling the south shore of the pool, thus never flushing or disturbing a single bird.

So don’t just drive by those big puddles, stop and have a look. You never know what you might find.

We’ve got the summertime blues for you, right here at susquehannawildlife.net…

…so don’t let the summertime blues get you down. Grab a pair of binoculars and/or a camera and go for a stroll!

If you’re feeling the need to see summertime butterflies and their numbers just don’t seem to be what they used to be in your garden, then plan an afternoon visit to the Boyd Big Tree Preserve along Fishing Creek Valley Road (PA 443) just east of U.S. 22/322 and the Susquehanna River north of Harrisburg. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources manages the park’s 1,025 acres mostly as forested land with more than ten miles of trails. While located predominately on the north slope of Blue Mountain, a portion of the preserve straddles the crest of the ridge to include the upper reaches of the southern exposure.

Fortunately, one need not take a strenuous hike up Blue Mountain to observe butterflies. Open space along the park’s quarter-mile-long entrance road is maintained as a rolling meadow of wildflowers and cool-season grasses that provide nectar for adult butterflies and host plants for their larvae.

Do yourself a favor and take a trip to the Boyd Big Tree Preserve Conservation Area. Who knows? It might actually inspire you to convert that lawn or other mowed space into much-needed butterfly/pollinator habitat.

While you’re out, you can identify your sightings using our photographic guide—Butterflies of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed—by clicking the “Butterflies” tab at the top this page. And while you’re at it, you can brush up on your hawk identification skills ahead of the upcoming migration by clicking the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab. Therein you’ll find a listing and descriptions of hawk watch locations in and around the lower Susquehanna region. Plan to visit one or more this autumn!

Those mid-summer post-breeding wanders continue to delight birders throughout the Mid-Atlantic States. One colorful denizen of ponds and wetlands that has yet to put in an appearance in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed this year is the Black-bellied Whistling Duck. You might remember this species from earlier posts describing the fortieth anniversary of your editor’s journey to the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Like many other birds, the Black-bellied Whistling Duck has been extending its range north from Texas, Florida, and other states along the Gulf Coastal Plain. Populations of these waterfowl are chiefly resident birds with some short-distance movement to find suitable habitat for feeding and nesting. They are not usually migratory, so summertime wandering may be the mechanism for their discovery of new habitats advantageous for nesting in areas north of their current home.

Presently, at least two dozen Black-bellied Whistling Ducks are being seen regularly at a stormwater retention pond in a housing subdivision along Amalfi Drive west of Smyrna, Delaware. This small population of avian tourists has spent at least two summers in the area. Just yesterday, Black-bellied Whistling Ducks were seen and photographed about ten miles to the east at Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Nine were counted there while 27 were being watched simultaneously at the Amalfi site. Earlier this week, a single Black-bellied Whistling Duck visited the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge in Philadelphia, indicating that the influx of these vagrants has transited the entire Delmarva Peninsula and entered Pennsylvania. So while you’re out watching for those first southbound migrants of the year, be on the lookout for wayward wanderers too—wanderers like Black-bellied Whistling Ducks!

Here in a series of photographs are just a handful of the reasons why the land stewards at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area and other properties where conservation and propagation practices are employed delay the mowing of fields composed of cool-season grasses until after August 15 each year.

Right now is a good time to visit Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area to see the effectiveness a delayed mowing schedule can have when applied to fields of cool-season grasses. If you slowly drive, walk, or bicycle the auto tour route on the north side of the lake, you’ll pass through vast areas maintained as cool-season and warm-season grasses and early successional growth—and you’ll have a chance to see these and other grassland birds raising their young. It’s like a trip back in time to see farmlands they way they were during the middle years of the twentieth century.

Have you purchased your 2023-2024 Federal Duck Stamp? Nearly every penny of the 25 dollars you spend for a duck stamp goes toward habitat acquisition and improvements for waterfowl and the hundreds of other animal species that use wetlands for breeding, feeding, and as migration stopover points. Duck stamps aren’t just for hunters, purchasers get free admission to National Wildlife Refuges all over the United States. So do something good for conservation—stop by your local post office and get your Federal Duck Stamp.

Still not convinced that a Federal Duck Stamp is worth the money? Well then, follow along as we take a photo tour of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge. Numbers of southbound shorebirds are on the rise in the refuge’s saltwater marshes and freshwater pools, so we timed a visit earlier this week to coincide with a late-morning high tide.

As the tide recedes, shorebirds leave the freshwater pools to begin feeding on the vast mudflats exposed within the saltwater marshes. Most birds are far from view, but that won’t stop a dedicated observer from finding other spectacular creatures on the bay side of the tour route road.

No visit to Bombay Hook is complete without at least a quick loop through the upland habitats at the far end of the tour route.

We hope you’ve been convinced to visit Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge sometime soon. And we hope too that you’ll help fund additional conservation acquisitions and improvements by visiting your local post office and buying a Federal Duck Stamp.

Visitors stopping by Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area this week found yet another post-breeding wanderer feeding in the shallows of the main lake and adjacent pond along Hopeland Road—a juvenile Little Blue Heron.

The juvenile Little Blue Heron is a white bird resembling an egret during its first year. At about one year of age, it begins molt into a deep blue adult plumage. Young birds are notorious for roaming inland and north from breeding areas along the Atlantic coast and throughout the south. They are a post-breeding wanderer nowhere near as rare as the Limpkin seen at Middle Creek a week ago; a few are found each summer in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

As oft times happens, birders attracted to see one unusual bird find another in the vicinity. So with fall shorebird migration ramping up, the discovery of something out of the ordinary isn’t a total surprise, particularly where habitat is good and people are watching.

The arrival of a Hudsonian Godwit is not an unheard of occurrence in the lower Susquehanna region, but locating one that sticks around and provides abundant viewing opportunities is a rarity. This adult presumably left the species’ breeding areas in Alaska or central/western Canada in recent weeks to begin its southbound movement. Hudsonian Godwits pass through the eastern United States only during the autumn migration, and the majority fly by without being noticed along a route that mostly takes them offshore of the Mid-Atlantic States.

Mid-summer can be a less than exciting time for those who like to observe wild birds. The songs of spring gradually grow silent as young birds leave the nest and preoccupy their parents with the chore of gathering enough food to satisfy their ballooning appetites. To avoid predators, roving families of many species remain hidden and as inconspicuous as possible while the young birds learn how to find food and handle the dangers of the world.

But all is not lost. There are two opportunities for seeing unique birds during the hot and humid days of July.

First, many shorebirds such as sandpipers, plovers, dowitchers, and godwits begin moving south from breeding grounds in Canada. That’s right, fall migration starts during the first days of summer, right where spring migration left off. The earliest arrivals are primarily birds that for one reason on another (age, weather, food availability) did not nest this year. These individuals will be followed by birds that completed their breeding cycles early or experienced nest failures. Finally, adults and juveniles from successful nests are on their way to the wintering grounds, extending the movement into the months we more traditionally start to associate with fall migration—late August into October.

For those of you who find identifying shorebirds more of a labor than a pleasure, I get it. For you, July can bring a special treat—post-breeding wanderers. Post-breeding wanderers are birds we find roaming in directions other than south during the summer months, after the nesting cycle is complete. This behavior is known as “post-breeding dispersal”. Even though we often have no way of telling for sure that a wandering bird did indeed begin its roving journey after either being a parent or a fledgling during the preceding nesting season, the term post-breeding wanderer still applies. It’s a title based more on a bird sighting and it’s time and place than upon the life cycle of the bird(s) being observed. Post-breeding wanderers are often southern species that show up hundreds of miles outside there usual range, sometimes traveling in groups and lingering in an adopted area until the cooler weather of fall finally prompts them to go back home. Many are birds associated with aquatic habitats such as shores, marshes, and rivers, so water levels and their impact on the birds’ food supplies within their home range may be the motivation for some of these movements. What makes post-breeding wanderers a favorite among many birders is their pop. They are often some of our largest, most colorful, or most sought-after species. Birds such as herons, egrets, ibises, spoonbills, stilts, avocets, terns, and raptors are showy and attract a crowd.

While it’s often impossible to predict exactly which species, if any, will disperse from their typical breeding range in a significant way during a given year, some seem to roam with regularity. Perhaps the most consistent and certainly the earliest post-breeding wanderer to visit our region is the “Florida Bald Eagle”. Bald Eagles nest in “The Sunshine State” beginning in the fall, so by early spring, many of their young are on their own. By mid-spring, many of these eagles begin cruising north, some passing into the lower Susquehanna valley and beyond. Gatherings of dozens of adult Bald Eagles at Conowingo Dam during April and May, while our local adults are nesting and after the wintering birds have gone north, probably include numerous post-breeding wanderers from Florida and other Gulf Coast States.

So this week, what exactly was it that prompted hundreds of birders to travel to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area from all over the Mid-Atlantic States and from as far away as Colorado?

Was it the majestic Great Blue Herons and playful Killdeer?

Was it the colorful Green Herons?

Was it the Great Egrets snapping small fish from the shallows?

Was it the small flocks of shorebirds like these Least Sandpipers beginning to trickle south from Canada?

All very nice, but not the inspiration for traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles to see a bird.

It was the appearance of this very rare post-breeding wanderer…

…Pennsylvania’s first record of a Limpkin, a tropical wading bird native to Florida, the Caribbean Islands, and South America. Many observers visiting Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area had never seen one before, so if they happen to be a “lister”, a birder who keeps a tally of the wild bird species they’ve seen, this Limpkin was a “lifer”.

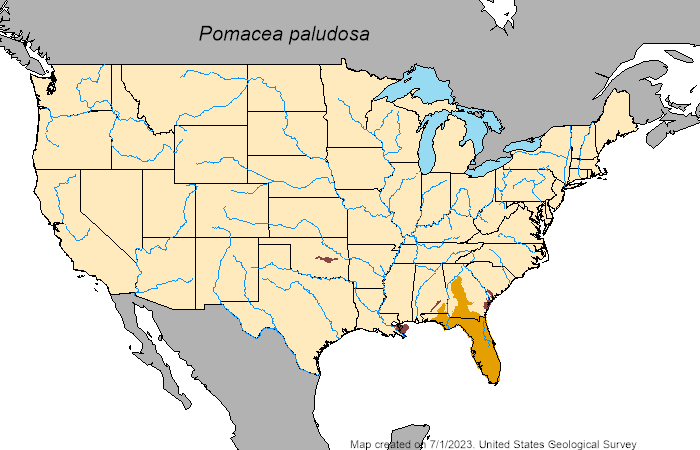

The Limpkin is an inhabitant of vegetated marshlands where it feeds almost exclusively upon large snails of the family Ampullariidae, including the Florida Applesnail (Pomacea paludosa), the largest native freshwater snail in the United States.

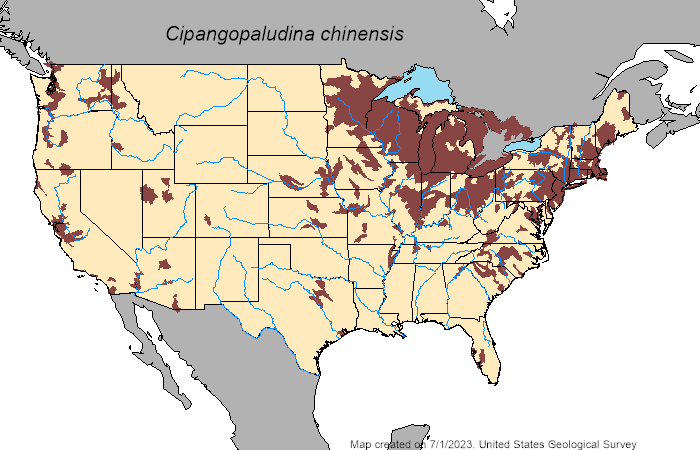

Observations of the Limpkin lingering at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area have revealed a pair of interesting facts. First, in the absence of Florida Applesnails, this particular Limpkin has found a substitute food source, the non-native Chinese Mystery Snail (Cipangopaludina chinensis). And second, Chinese Mystery Snails have recently become established in the lakes, pools, and ponds at the refuge, very likely arriving as stowaways on Spatterdock (Nuphar advena) and/or American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea), native transplants brought in during recent years to improve wetland habitat and process the abundance of nutrients (including waterfowl waste) in the water.

The Middle Creek Limpkin’s affinity for Chinese Mystery Snails may help explain how it was able to find its way to Pennsylvania in apparent good health. Look again at the map showing the range of the Limpkin’s primary native food source, the Florida Applesnail. Note that there are established populations (shown in brown) where these snails were introduced along the northern coast of Georgia and southern coast of South Carolina…

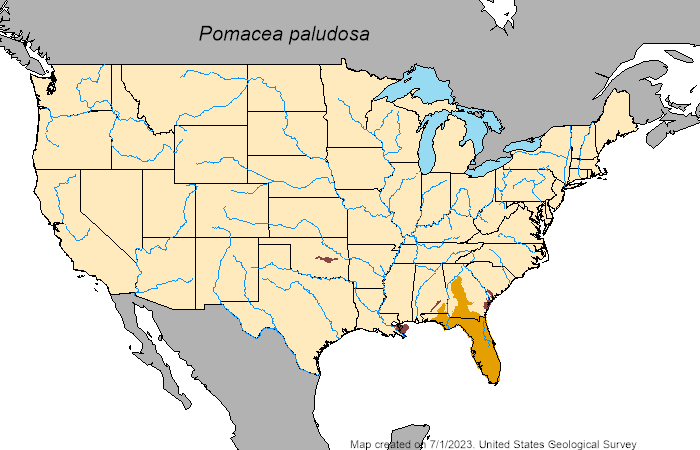

…now look at the latest U.S.G.S. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species map showing the ranges (in brown) of established populations of non-native Chinese Mystery Snails…

…and now imagine that you’re a happy-go-lucky Limpkin working your way up the Atlantic Coastal Plain toward Pennsylvania and taking advantage of the abundance of food and sunshine that summer brings to the northern latitudes. It’s a new frontier. Introduced populations of Chinese Mystery Snails are like having a Waffle House serving escargot at every exit along the way!

Be sure to click the “Freshwater Snails” tab at the top of this page to learn more about the Chinese Mystery Snail and its arrival in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Once there, you’ll find some additional commentary about the Limpkin and the likelihood of Everglade Snail Kites taking advantage of the presence of Chinese Mystery Snails to wander north. Be certain to check it out.

When you were young, you may have selected your tennis shoes because they promised to make you run faster and jump higher. Remember those? Then as you got a bit older, you may have really wanted the brand that would get you noticed—those overpriced status-symbol athletic shoes. As the years went by and you put on the extra pounds in all the wrong places, maybe it occurred to you that it might be a really good idea to get some exercise. So you went out and bought some stylish and expensive fitness footwear that promised to help you run faster and jump higher—and wore that pair to go shopping at the grocery store. Then you finally realized…

Here’s a look at some native plants you can grow in your garden to really help wildlife in late spring and early summer.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY TWELVE—June 1, 1983

“KOA Hammond, LA”

“We stopped early today — About 2:30 P.M. Cleaned the interior of the camper, washed the windows, and put everything where it belonged. The windshield was a buggy mess. Had supper according to the menu. Took pictures of the place. Had a shower. Loafed all evening.”

After being on the go for twelve to sixteen hours a day for more than a week, it was nice to catch up on our “housekeeping”, field notes, and rest. The campground, which was yet another nearly empty one, had an in-ground pool, so I decided to go for a swim. As I went through the gate, I noticed that the water was a little bit dull, not sparkling clear as if treated by the usual dose of chemicals. Upon getting closer, I could see what looked like a layer of mulm at the bottom of the pool, similar to the detritus and waste that accumulates atop the substrate in an otherwise clear aquarium tank. Needless to say, I postponed the swim. Later, when we happened to be in the office, I asked the owners about the pool and was momentarily puzzled when they told us that the entire campground had been flooded last month. This was at first surprising because no stream, creek, or river was in sight, but the land is so flat and the elevation so uniform in southwestern Louisiana that a couple of feet of water can inundate miles and miles of these lowlands. As on a beach or on a delta, building anything of value in a floodplain is risky business.

On June 2, we resumed our drive, then spent the night at the KOA campground in Sweetwater, Tennessee, at the same accommodations we visited while southbound on May 21. There, I finally had my refreshing swim. By the following evening, June 3, we had arrived back in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. During the trip from the Brownsville Airport to Lititz, Pennsylvania, the odometer had registered 1,945 miles.

This then, prompted and fortified by the notes kept by Russ Markert, have been your editor’s recollections from his ever-evaporating river of memories of an adventure forty years gone. I hope you’ve enjoyed this modern-style slide show describing our journey to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. I’m grateful to each of my traveling companions for inviting me to share this experience with them and am equally glad to have had the opportunity to share the story of our trip with you.

If traveling to see the wildlife and plant communities of south Texas seems like something that might interest you, I strongly urge you to go. Many more tropical species, including native parrots, are now found north of the border and the opportunity to see vagrants is still better there than anywhere else in the country. The hundreds of species of butterflies and the spectacular migrations of the Neotropical birds that nest here in the the higher latitudes make it a place you need to visit at least once in a lifetime. The cooler months of the year can be a comfortable time to make the trip. You’ll see wintering birds from both eastern and western portions of the United States and Canada, some in numbers that might amaze you.

If the Lower Rio Grande Valley is something outside your means, then may I suggest a visit to ZooAmerica in Hershey, Pennsylvania. The theme of the collection is North American wildlife and the self-guided tour is organized by regional habitat types including the southern swamps and the southwestern deserts and scrubland. Some of the animals we saw on our expedition, and some that we missed, are among the species under their care.

That’s it folks. Until next time, adiós amigos.

IN MEMORIAM

J. E. Russel Markert (1912-1984)

Harold B. Morrin (1924-2012)

Steven J. Santner (1948-2021)

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY ELEVEN—May 31, 1983

“AOK Camp, Texas — 7 Miles S. of Kingsville”

“Went south to the 1st rest stop south of Sarita — No Tropical Parula. Lots of other birds. We added Summer Tanager and Lesser Goldfinch.”

The Sarita Rest Area along Route 77 was like a little oasis of taller trees in the Texas scrubland. We received reports from the birders we met yesterday at Falcon Dam that recently, Tropical Parula had been seen there. We searched the small area and listened carefully, but to no avail. For these warblers, nesting season was over. We were surprised to find Lesser Goldfinches in the trees. Back in 1983, the coastal plain of Texas was pretty far east for the species. Steve was a bit skeptical when we first spotted them, but once they came into plain view, he was a believer. I recall him finally exclaiming, “They are Lesser Goldfinches.” Summer Tanager was another wonderful surprise. Today, the Sarita Rest Area remains a stopping point for birders in south Texas. Both Lesser Goldfinch and Tropical Parula were seen there this spring.

After our roll of dice at the Sarita Rest Area, we continued south through the King Ranch en route back to Brownsville.

“Saw a Coyote on the way.”

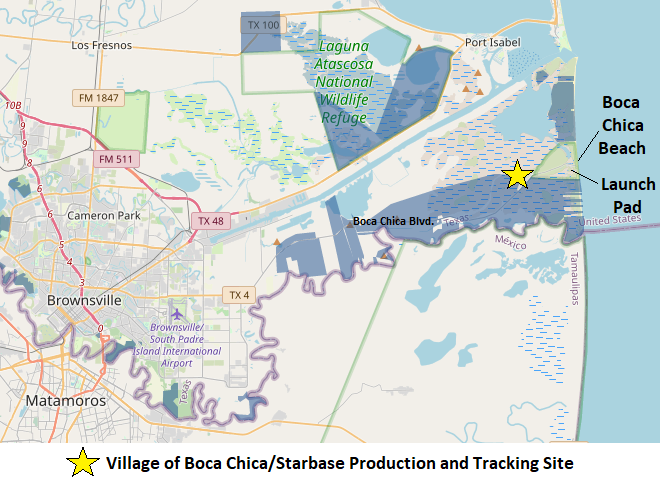

“Took Steve to the airport and drove out to Boca Chica where Harold went swimming.”

The drive from Brownsville out Boca Chica Boulevard to the Gulf of Mexico passes through about 18 miles of the outermost flats of the river delta that is the Lower Rio Grande Valley. This area is of course susceptible to the greatest impacts from tropical weather, especially hurricanes. During our visit, we passed a small cluster of ranch houses about two or three miles from the beach. This was the village known as Boca Chica. Otherwise, the area was desolate and left to the impacts of the weather and to the wildlife.

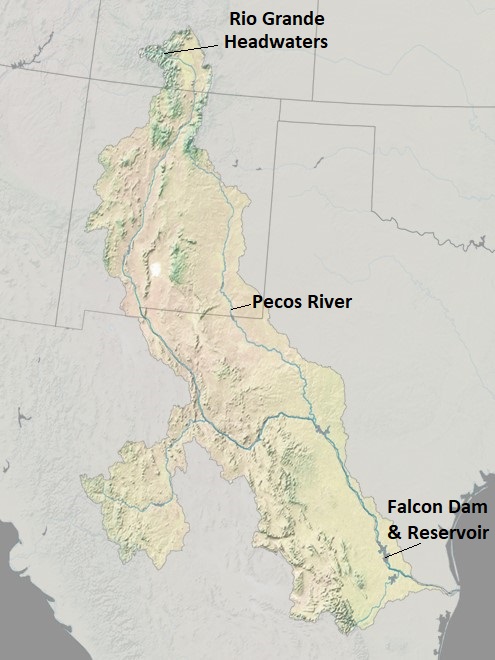

The mouth of the Rio Grande, and thus the international border with Mexico, was and still is about two miles south of Boca Chica Beach. Before the construction of dams and other flood control measures on the river, the path of the Rio Grande through the alluvium deposits on this outer section of delta would vary greatly. Accumulations of eroded material, river flooding, tides, and storms would conspire to change the landscape prompting the river to seek the path of least resistance and change its course. Surrounding the segments of abandoned channel, these changes leave behind valuable wetlands including not only the resacas of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, but similar features in tidal sections of the outer delta. When left to function in their natural state, deltas manage silt and pollutants in the waters that pass through them using ancient physical, biological, and chemical processes that require no intervention from man.

Harold was determined to go for a swim in the Gulf of Mexico before boarding a flight home. We all liked the beach. Why not? You may remember trips to the shore in the summertime. Back in the pre-casino days, we used to go to Atlantic City, New Jersey, to visit Steel Pier. For the first three quarters of the twentieth century, Steel Pier was the Jersey Shore’s amusement park at sea. There were rides, food stands, arcades, daily concerts with big name acts, diving shows, and ballroom dances.

There were, back then, attractions at Steel Pier that were creatively promoted to give the visitor the impression that they were going to see something more profound or amazing than was was delivered. You know, things advertised to draw you in, but its not quite what you expected.

For example, there was an arcade game promising to show you a chicken playing baseball. Okay, I’ll bite. Turns out the chicken did too. You put your money in the machine and watched as the chicken came out and rounded the diamond eating poultry food as it was offered at each of the bases. Hmmm…to suggest that this was a chicken playing baseball seems like a bit of a stretch.

They had a diving bell there too. Wow! We’ll go below the waves and view the fish, octopi, and other sights through the water-tight windows while we descend to the ocean floor. You would pay to get inside, then they would lower the bell down through a hole in the pier. Once below the rolling surf, you would get to look at the turbid seawater sloshing around at the window like dirty suds in a washing machine. If you were lucky, some trash might briefly get stuck on the glass. To imply that this was a chance to see life beneath waves was B. S., and I don’t mean bathysphere.

Then there was a girl riding a diving horse. You would hike all the way to the end of the pier and watch the preliminary show with these divers plunging through a hole in the deck and into the choppy Atlantic below. They were very good, but no, we never saw Rodney Dangerfield do a “Triple Lindy” there. And then it was time for the finale. Wow, is that horse going to dive in the ocean? How do they get the horse back up on the pier? Forget it. Instead of that, they walked poor Mr. Ed up a ramp into a box, then the girl climbs on his back, the door opens, and she nudges Ol’ Ed to into a plunge followed by a thumping splash into a swimming pool on the deck. Not bad, but not what we were expecting. Since we had to walk almost a quarter of a mile out to sea to get there, they kinda led us to believe that the amazing equine was going to leap into the Atlantic—horse hockey!

Preceding all this fun was a guy back in the early 1930s, William Swan, who, in June 1931, flew a “rocket-powered plane” at Bader Field outside Atlantic City. The plane was actually a glider on which a rocket was fired producing about 50 pounds of thrust to boost it airborne after assistants got it rolling by pushing it. In newspaper articles and on newsreels afterward, he would promote the future of rocket planes carrying passengers across the ocean at 500 miles per hour. Using a glider equipped with pontoons for landing in the ocean, he promised to make several flights daily from Steel Pier. Those who came to see him may have, at best, watched him fire small rockets he had attached to his craft—little more.

What does all this have to do with Boca Chica Beach? It turn out two years later, William Swan is hyping a new innovation—a rocket-powered backpack. He’d demonstrate it during a skydiving exhibition at the Del-Mar Beach Resort, a cluster of 20 cabins and community buildings on Boca Chica Beach. According to his deceptive promotions, Swan would jump out of a plane and light flares as he fell. Then he’d ignite the backpack rocket and land on the shoreline in front of the crowd. The event was expected to draw 3,000 carloads of people. When the big day came, just over 1,000 cars showed up. The event was a bust and the weather was bad, cloudy with a mist over the gulf. During a break in the clouds, the pilot took Swan aloft. Swan ordered him out to sea and to 8,500 feet, a higher altitude than planned. Then he jumped. He dropped the flares, which didn’t then ignite, and neither did the rocket. He opened his chute at 6,000 feet and the crowd watched as Swan drifted into the mist offshore and was never seen again. There were rumors both that he used the stunt as a way to flee to Mexico to start a new life and that he had committed suicide. Others believed he died accidentally. To learn the full story of Billy Swan, check out The Rocketeer Who Never Was, by Mark Wade.

Forward fifty years to our visit to Boca Chica Beach. The Del-Mar Beach Resort, built in the 1920s as a cluster of 20 cabins and a ballroom, was gone. It was destroyed by a hurricane later in the same year Swan disappeared—1933. The resort, which was hoped would be the start of a seaside vacation city, never reopened. In 1983, we saw just a handful of beach goers and the birds, that’s it. One could look down to the south and see the area of the Rio Grande’s mouth and Mexico, but there were no structures of note. It was peaceful and alive with wildlife. We were sorry we didn’t have more time there.

“Here we added Least Tern, Brown Pelican and Sandwich Tern.”

Today, the Village of Boca Chica and Boca Chica Beach are the location of SpaceX’s South Texas Launch Facility. Those of the village’s ranch houses built in 1967 that have survived hurricane devastation over the years have been incorporated into the “Starbase” production and tracking facility. The launch pad and testing area is along the beach just behind the dunes at the end of Boca Chica Boulevard.

The latest launch, just more than a month ago, was the maiden flight of “Starship”, a 394-foot behemoth that is the largest rocket ever flown. The “Super Heavy Booster” first stage’s 33 Raptor engines produce 17.1 million pounds of thrust making Starship the most powerful rocket ever flown. See, things really are bigger in Texas.

Last month’s unmanned orbital test launch ended when the Starship spacecraft failed to separate at staging. As the booster section commenced its roll manuever to return to the launch pad, the entire assembly began tumbling out of control. It exploded and rained debris into the gulf along a stretch of the downrange trajectory.

Development of Starbase is opposed by many due to noise, safety, and environmental concerns. Boca Chica Boulevard (Texas Route 4) is frequently closed due to activity at the launch pad site, thus excluding residents and tourists from visiting the beach. With over 1,200 people already working at Starbase, demand for housing in the Brownsville area has increased. Some have accused SpaceX CEO Elon Musk of promoting gentrification of the area—running up housing prices to force out the lower-income residents. He has responded with a vision of a new city at Boca Chica, his “space port”.

Does history have an applicable lesson for us here? When Musk talks about going to the Moon and Mars, or ferrying a hundred people around the world on his Starship, is it just another Steel Pier-style deception? Is Musk a modern-day William Swan? A very talented marketer? Could be. And is the whole thing setting up a large-scale replay of the Del-Mar Beach Resort’s demise in 1933? Is building a city on the outer edges of a river delta asking for an outcome similar to the one suffered by New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina? It’s likely. After all, building on or near a beach, floodplain, or delta is a short-sighted venture to begin with. If the party doing the developing doesn’t suffer the consequences of defying the laws of nature, one of the poor suckers in the successive line of buyers and occupants will. This isn’t rocket science folks. Its weather, climate, and erosion, and its been altering coastlines, river courses, and the composition and distribution of life forms on this planet for millions of years. And guess what. These factors will continue to alter Earth for millions of years more after man the meddler is long gone. You’re not going to stop their effects, and you’re not going to escape their wrath by ignoring them. So if you’re smart, you’ll get out of their way and stay there!

Billy Swan was probably broke when he came to Boca Chica. He reportedly borrowed 20 bucks from the resort operator just to cover his personal expenses during his backpack rocket event. Elon Musk comes to Boca Chica with over 100 billion dollars and capital from other private investors to boot. Despite some obvious exaggerations about colonizing the Moon, Mars, and other celestial bodies, he just might be able to at least get people there for short-term visits. And that’s quite an accomplishment.

“Then took Harold to the airport. We left him at 3:30 and headed north on Route 77, got as far as Victoria. Had a flat on the way. Larry had the spare on in 10 minutes. We stopped at a picnic area for the nite, because we could not find the camping area.”

If we were going to have a flat, we had it at the right place. We were just outside Raymondville, Texas, at a newly constructed highway interchange. The wide, level shoulder allowed us to get the camper off to the side of the road in a safe place to jack it up and change the tire. Easy. We were thereafter homeward bound.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY TEN—May 30, 1983

“Falcon Dam State Park, Texas”

“9:30 — Breakfast — The Pauraque sang all nite and the Mockingbird sang half the nite and interrupted my sleep.”

Before leaving the campground, we paid a final visit to the shores of the reservoir. We saw Anhinga and Little Blue Heron among the other water birds we had seen there previously.

“Now to the spillway again. We got lucky — A Green Kingfisher flew in and gave us great views. Cliff Swallows were plentiful. The Green Herons were fishing and so was a Kiskadee Flycatcher. Black Vultures were flying around. A Groove-billed Ani was very much in evidence.”

The little Green Kingfisher (Chloroceryle americana), after all the effort we finally saw one. It was just half the size of the Ringed Kingfisher we saw at the spillway one day earlier.

“Here we met Bill Graber from San Antonio. Ron and 3 women—Sandra from Wales, 1 from Oregon, and 1 from San Antonio… We all walked to the spot for the Ferruginous Owl”

We again followed Father Tom’s directions; “Park at spillway, walk the road to a fence, go right to the river, follow fence to a big dip (gully).”

Once in the designated area, several of us began searching around the vicinity for the owls. I was out of sight of the others and was examining a long procession of tropical leafcutter ants, possibly the Texas Leafcutter Ant (Atta texana). Their foraging trail had two single-file lanes—worker ants carrying dime-sized pieces of leaves to the nest and worker ants returning to the tree to harvest more. The ants’ path of travel stretched for more than one hundred feet down the limbs and trunk of the source tree, across the sandy ground, over a fallen log, across more sandy ground, through some leaf litter in the shrubs, and to the nest, where the foliage will be used to cultivate fungi (Lepiotaceae) for food. Thousands of worker ants were marching the route while others guarded their lines—fascinating.

Suddenly, I heard a commotion in the brush. Collared Peccaries (Dicotyles tajacu), also known as Javelina, on the run and headed right my way! The others must have unknowingly spooked them. In an instant I scrambled to my feet and bounded up the trunk of a willow tree that was strongly arching toward the river and had partially fallen after the bank had washed away. There I stood atop the nearly horizontal trunk as between 6 and 10 grunting peccaries bustled past in a cloud of dust. Just as fast as they had appeared, they were gone.

I walked back toward the gully and as I approached, I could see everyone peering at something in the dense foliage of the trees overhanging the river.

“…eventually Sandra spotted one coming in. Another was also seen in a much better position. We all saw the 2 black spots on the back of his head when he turned his head 180°. It looked like another face.”

They had found the Ferruginous Pygmy Owls, right where Father Tom said they would be. But they weren’t easy to see. And they were tiny. Make a loose fist—that’s about the size of a Ferruginous Pygmy Owl. We had to take turns standing at favorable places where there was a less-obstructed view of each bird. I’m not certain that anyone was able to get photographs. The shade was too dark for my equipment to get a favorable exposure. Such had been the case for many of the birds we found in the riparian forest. This owl was a life list species for everyone in our group and for most of the others. Like the Green Kingfisher, the owls were just barely within the A.B.A. area, on limbs stretching out above the waters of the Rio Grande.

“Then we came back to the picnic ground and walked the river’s edge for a 1/4 mile — Nothing extra, except an Altamira Oriole.”

I again did a little wading in the Rio Grande to cool down after spending hours in the hot scrubland/forest.

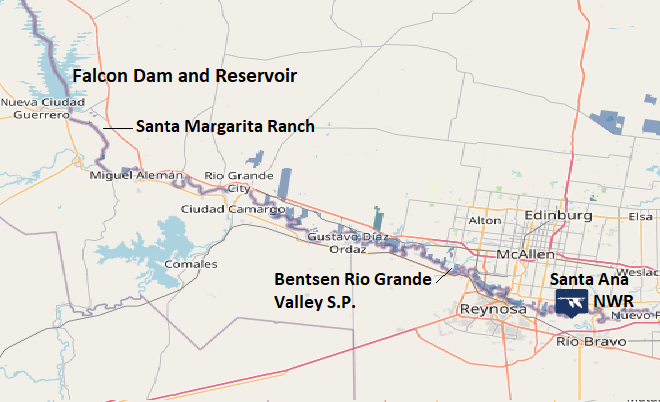

“On the way back to Brownsville, we stopped at Santa Margarita again with no Brown Jay luck.”

Though we never did bump into the roving band of Brown Jays at Santa Margarita Ranch, they were there, and they’re a species that’s still there today.

“On to Brownsville for good sightings of the Clay-colored Robin at the radio station.”

We returned to the radio transmitter site at Coria and Los Ebanos in Brownsville for yet another attempt to find Clay-colored Robins/Thrushes. After again securing permission from Mr. Wilson to have a look around, we at last had success and found a pair of Clay-colored Thrushes moving about in the boughs of the shade-casting tress and shrubs. With some persistence, we all got binocular views of these earth-tone rarities from Mexico.

While in Brownsville, we thought it a good idea to dabble a bit in the experiences of local consumer culture, so we drove downtown. After finding a place to park the camper, we commenced to going for an international stroll over the bridge that crosses the Rio Grande into Matamoras, Tamaulipas, Mexico. It was our first legal incursion south of the border. (In recent days, we may have stepped back-and-forth over the line a couple of times while wading in the river below Falcon Dam.)

Once in Matamoros, we entered the bank. Steve wanted to get some Mexican currency and coins for his collection, so we stepped inside. It was a typical classical-style masonry building like most banks built early in the twentieth century were, but this one had very few accoutrements inside. There was a big vault, some cash drawers, maybe a desk and a chair, and that was it. The doors were left open to get a flow of dirty air in the place because there was no air conditioning. No loan department or Christmas Clubs here, just dollars for pesos.

Upon leaving the bank and heading into the town, we were solicited by the unlicensed curbside pharmacists selling herbs and other home remedies. Not for me, I had one thing in mind on this shopping trip.

We walked up the street to step inside some of the numerous tourist shops—stuff everywhere. The other men bought a few post cards. For a friend back home, I bought a key chain with a tiny pair of cowboy boots attached. Having heard that cowboy boots could be had for cheap south of the border, he had given me his size requirements and asked that I should get him a pair if the price was right. Well, the price wasn’t that great in the tourist town section of the city, so I got him the key chain instead.

After about an hour, we were headed back over the bridge into Brownsville. Along the pedestrian walkway, there was a United States Customs checkpoint one had to pass before entering the country. The customs officer asked the usual questions and after telling him we were only in Mexico for an hour, he queried, “Did you buy anything that you’re bringing back into the country.” Having an item to declare, I told him yes, I bought a pair of cowboy boots. He looked down at my rubber-toed canvas sneakers, then looked at Russ, Harold, and Steve, who obviously weren’t carrying or wearing boots, and he snapped, “Where are they?” I pulled the wax paper bag with the key chain inside from my pocket. He called me a smart ass and waved us on. We chuckled.

The only bird species seen during or short trek into Matamoros? House Sparrow.

In the forty years since our visit to the Rio Grande Valley, the rate of northbound human migration across the river, and particularly the amount of smuggling activity that uses the migration as a diversion to cover its operations, has surely taken the fun out of being on the border. Many of the places we visited are no longer open to the public, or access is restricted and subject to tightened security. Santa Margarita Ranch, for example, now allows guided tours only. Falcon Dam changed its security practices after one of a pair of opposing drug cartels escalated their mutual dispute by planting explosives there—threatening to blow it up to hamper crossings by its opponent’s smugglers in the fordable waters downstream.

Fortunately for today’s birder, many of the tropical specialties have inched their range north of the Rio Grande’s banks and can be found on accessible public and private lands outside the immediate tension zone. National Wildlife Refuges and Texas State Parks provide access to some of the best habitats. Places like the King Ranch even offer guided bird and wildlife tours on portions of their vast holdings where many border species including Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, Crested Caracara (Caracara plancus), Green Jay, Vermillion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus obscurus), Northern Beardless-Tyrannulet (Camptostoma imberbe), and the tropical orioles are now found. So don’t let the state of dysfunction on the border stop you from visiting south Texas and its marvelous ecosystems. It’s still a birder’s paradise!

“We ate supper at Luby’s Cafeteria and headed north on Route 77 for the Tropical Parula.”

Harold was very pleased to have added Hook-billed Kite, Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, and Clay-colored Thrush to his A.B.A. life list, so he offered to buy dinner. After visiting a mail box to get a few postcards on their way, we ate at Luby’s Cafeteria in Brownsville, which was an interesting experience for that time period. Luby’s was a regional restaurant chain. You could get in line there and select anything you wanted, then pay for it by the item. Luby’s predated the all-you-can-eat salad bar and buffet craze that would sweep the restaurant industry in coming years. Under the circumstances, it was perfect for us. After not eating much all week due to the hot, humid conditions that accompanied the unusually rainy weather, our appetites begged satisfaction—but the heat hadn’t relented, so we didn’t want to overdo it. The staff at Luby’s didn’t blink an eye at us entering the restaurant wearing field clothes. It was the first climate-controlled space we had enjoyed all week—very refreshing. We really enjoyed the experience and it recharged us all.

Near Raymondville along Route 77, a set of electric wires strung on tall wooden poles paralleled the highway. These poles were hundreds of yards away from road, but seeing a raptor atop one, we stopped and got out the spotting scope. It was yet another south Texas specialty, a White-tailed Hawk (Buteo albicaudalus), a bird of grassland and brush. Its range north of Mexico is limited to an area of Texas from the Lower Rio Grande Valley north through the King Ranch to just beyond Kingsville. A short while later, we saw one or two more on our way through the King Ranch.

“Saw a flock of White-rumped Sandpipers when we stopped for gas.”

Lest one might think that traveling through parts of five south Texas counties to go from Falcon Dam back east through the Lower Rio Grande Valley to Brownsville and then north for a return stay at the A.O.K. campground is just another day of birding punctuated by some driving every now and again, consider the mileage racked up on the odometer today—259 miles. Even the counties are bigger in Texas.

We topped off the fuel tank at a service station near Sarita, Texas, and saw the White-rumped Sandpipers (Calidris fuscicollis) in a pool of rainwater among the scrubland at roadside.

“We stopped at the AOK Camp Ground 7 miles south of Kingsville and will return to get the parula at the first rest stop south of Sarita. Now 9:30 CDST.”

WHY WORRY ABOUT SPIDERS AND SNAKES?

Back at the old A.O.K. campground, this time with Harold and Steve, we decided to have a camp fire for the first time on the trip. We bought a bundle of wood at the camp office and soon had it crackling. I broke out the harmonica, but knowing no cowboy tunes, soon stashed it away. We had better things to do. Did we bake some beans in an iron kettle on the hot embers? No, we ate plenty at Luby’s. Did we toast marshmallows on sticks and make s’mores? Nope. Did we roast our weenies and warm our buns? No, not that either. We simply sat around recapping our trip while scratching our itchy ankles. Seems each of us was hosting chigger larvae and these parasites, upon maturing to nymphs and departing, left irritating wounds in our skin where they had been feeding—right in the hollow of our ankles.

Chiggers (Trombiculidae), like spiders and ticks, are arachnids. They thrive in humid environments as opposed to arid climes. Our best guess was that we had picked them up while hiking around in the subtropical riparian forests along the Rio Grande in the early days of the trip. My wounds eventually left little red pimples where each tiny larva had been feeding. They healed about a week after I got home. Due to the severity of his wounds, Steve cancelled a second week of his trip. On his own, he was going to continue west along the Rio Grande to the area of Big Bend National Park, but instead booked a flight home. Chigger larvae are stealthy little sneaks—we never had any clue they got us until they were gone. So why worry about spiders and snakes?

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY NINE—May 29, 1983

“Falcon Dam State Park, Texas”

“To the spillway area after breakfast and saw Ringed Kingfisher, Baird’s Sandpiper, and 2 Black-necked Stilts. Stopped to photograph the Swainson’s Hawk which had flown in a tree. Also saw a Blue Grosbeak.”

The Ringed Kingfisher (Megaceryle torquata) was notably larger than the Belted Kingfishers with which we were so familiar, so it was easy to identify. This was yet another tropical species found north only as far as the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Baird’s Sandpiper was a pretty good find for this location in late May.

“We drove to Santa Margarita Ranch to search for the elusive Brown Jay.”

While en route to Santa Margarita Ranch, we stopped twice to photograph birds we spotted along the way.

Beside the road just outside the entrance to the ranch, we observed a Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps), a tiny chickadee-like like bird with a yellow head and throat. Verdins reside in both thornscrub and desert throughout the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

“Rancho Santa Margarita is a group of 8 houses. Cattle roam at will. We walked a long way along the river — No luck. Had lunch in the camper and repeated the morning walk. Cattle dung all over the place. The dung rollers were as interesting to watch as the leaf-carrying ants. Met a Mr. McQueary who had seen them 30 min. ago, so he led us to where he had seen them, but — No luck.”

Upon arriving at Santa Margarita Ranch intending to find Brown Jays (Psilorhinus morio), we drove over the in-ground cattle gate at the entrance and back the dirt driveway to the small cluster of houses where we parked. We checked in with a resident there and slipped them a dollar or two a head for letting us spend the day on their land. As we walked away from the houses, we noticed some intermittent movement in a pile of construction debris along the dirt road leading to the river. Initially thinking we may have caught glimpses of some small rodents dashing around, we watched patiently until we saw at least two Blue Spiny Lizards (Sceloporus cyanogenys) among the lumber and tin. The pair was obviously finding insects or other sources of prey there

To find Brown Jays, one of the five target species of the trip, Father Tom had advised us to follow the advice in James Lane’s A Birder’s Guide to the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. The recommendations contained therein brought us to Santa Margarita Ranch. As was the case upriver near Falcon Dam, the Tamaulipan Saline Thornscrub that covers much of the property turns abruptly to subtropical riparian forest near the banks of the Rio Grande where wetter soils predominate. The habitat was excellent, and we were certain the birds were there, but despite significant effort, we just couldn’t bump into Brown Jays at Santa Margarita Ranch.

We did however get good looks at another Hook-billed Kite sailing above the trees downriver. During our second walk, Harold, Steve, and I waded down a short section of the Rio Grande in hopes of getting better looks into an area of shoreline forest too thick to enter by land. Despite recent rains, the water was low, restricted by gates at Falcon Dam to little more than the flow needed to operate the turbines and generate electricity. We saw orioles, Red-billed Pigeon, and Great Kiskadee—but no Brown Jays.

“On the way out…found a nest of Pyrrhuloxia and saw a 6 ft. snake hanging from a bush with a rabbit in his mouth. The snake caught the rabbit by the shoulder and it was working hard to get free. Finally the snake dropped the rabbit, and they both went out of sight.”

As we eased our way out the dirt road at Santa Magarita Ranch, we began hearing a blood-curdling series of squeals. Russ stopped the van and as we peered into the thornscrub, we could catch glimpses of an Eastern Cottontail thrashing around. At first we thought it had somehow become snagged in the quagmire of prickles on the dense vegetation. Then we spotted the snake draped over the shrubs and attempting in vain to lift the cottontail off the ground. The struggle, and the squealing, continued for several minutes as we labored to identify the snake. As the snake attempted to reposition the cottontail so that it could swallow it head first, the rabbit broke free and escaped. All was silent as the snake quickly fled as well. As it slithered away we could see just how long it really was—5 to 6 feet or more. You know, things really are bigger in Texas. Based upon its large size, overall tan-brown color, and the rapid speed with which it left the scene, we determined it was a Western Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum testaceus).

“Back to the spillway at Falcon Dam — No luck. Met Ron Huffman who is leading a trip for 3 women. We will meet him at the spillway tomorrow AM early. Back at our camp site for supper — shower and shave. The Lesser Nighthawks were trilling late in the evening.”

During the evening, we found Black-throated Sparrow (Amphispiza bilineata) and Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata) in the area of the campsite. Then, as darkness settled in, the calls of Common Pauraque, Common Nighthawks, and Lesser Nighthawks (Chordeiles acutipennis) commenced. We walked down the road to a spot where we could overlook a lower-lying area of thornscrub in hopes of catching a glimpse of some of these nightjars, particularly the latter species, as they patrolled for flying insects. But under cloudy skies and being miles from any man-made sources of light, it was too dark to see anything flying around.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY EIGHT—May 28, 1983

“Bentsen State Park, Texas”

“Alarm at 6:00 A.M. After breakfast we traveled to Falcon State Park and toured the whole camp area, stopping many places to observe birds. We ran up a good list.”

And so we left what had been our home for the last several days and headed west. In the forty years since our departure that morning, Bentsen-Rio Grande State Park has experienced a number of operational changes. Today, it is a World Birding Center site. For conducting the seasonal hawk census, a tower has been erected to provide counters and observes with an unrestricted view above the treetops. If you wanted to camp in the park now, you would need reservations and would have to hike your gear in to one of only a few primitive campsites. Trailer and motor home accommodations no longer exist. A tram service is now available for touring the park by motor vehicle.

Falcon State Park is located along the east shore of Falcon Reservoir. There are no shade trees beneath which one can escape the scorching rays of the sun on a hot day. This is the easternmost section of the scrubland’s Tamaulipan Saline Thornscrub, a xeric plant community of head-high brush found only on clay soils with a particularly high salinity. Many of the plants look similar to other varieties of shrubs and small trees with which one may be familiar, except nearly all of them are covered with nasty thorns and prickles. And yes, there are cactus. You can’t make your way bushwhacking cross country without obtaining cuts, gashes, and scars to show for it. The Falcon State Recreation Area bird checklist published in 1977 has a nice description of the plants found there—mesquite, ebano, guaycan, blackbrush and catclaw acacia, granjeno, coyotillo, huisache, tasajillo, prickly pear, allthorn, cenizo, colima, and yucca. In the margins between the thornscrub growth, there is an abundance of grasses and wildflowers. On nearby ridges, Tamaulipan Calcareous Thornscrub, a similar xeric plant community, occupies soils with a higher content of calcium carbonate. Together, these communities comprise much of the Tamaulipan Mezquital ecoregion of scrublands in Starr County and western Hidalgo County in the Rio Grande valley of Texas.

After being greeted by a Greater Roadrunner at the campsite, we took a walk to the nearby shoreline of the reservoir. We spotted Olivaceous Cormorants perched on some dead limbs in the water nearby. Known today as Neotropic Cormorant (Phalacrocorax brasilianus), it is yet another specialty of the Rio Grande Valley. Elsewhere on or near the water—Cattle Egret, Great Egret, Black-bellied Whistling Duck, Osprey, Common Gallinule, Killdeer, Laughing Gull, Forster’s Tern (Sterna forsteri), Least Tern, and Caspian Tern were seen.

In the thornscrub around the campground, which, like Bentsen-Rio Grande State Park, we had pretty much to ourselves, we saw Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Curve-billed Thrasher, White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, Ground Dove, Inca Dove, and White-tipped Dove. A single Chihuahuan Raven was a fly by. We saw and smelled several road-killed Nine-banded Armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), but never found one alive.

Then, it started to rain. Not just a shower, but a soaker that persisted through much of the day. Rainy days can make for great birding, so we kept at it. Unfortunately, such days aren’t too ideal for photography, so we did only what we could without ruining our equipment.

“Finally we drove to the spillway of the dam and parked.”

Falcon Dam was another of the numerous flood-control projects built on the Rio Grande during the middle of the twentieth century. Behind it, Falcon Reservoir stores water for irrigation and operation of a hydroelectric generating station located within the dam complex. Construction of the dam and power plant was a joint venture shared by Mexico and the United States. The project was dedicated by Presidents Adolfo Ruiz Cortines and Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953.

Rainy days aside, the route precipitation takes to reach the Falcon Reservoir and the Lower Rio Grande Valley includes hundreds of miles through arid grasslands and scrublands. Along the way, much of that water is lost to natural processes including evaporation and aquifer recharge, but an increasing percentage of the volume is being removed by man for civil, industrial, and agricultural uses. Can the Rio Grande and its tributaries continue to meet demand?

“On the way in we saw and photographed an apparent sick or injured Swainson’s Hawk. We approached it very close.”

“At the spillway we sat in the camper, except when the rain slackened, then we stood out and watched in vain for the Green or Ringed Kingfisher, which we never did see.”

At the spillway House Sparrows, Rough-winged Swallows, and Cliff Swallows were nesting on the dam, the latter two species grabbing flying insects above the waters of the Rio Grande.

“I made dinner here at this spillway and we continued to watch. The rain almost stopped, so we walked down the road about 1 1/2 miles, during which time we saw a lifer for Harold — Hook-billed Kite. We followed Father Tom’s directions to a spot for the Ferruginous Owl — no luck.”

“Back at the spillway we had supper and then repeated the hike — no Ferruginous Owl, but a Barn Owl and Great Horned Owl. Back to our #201 campsite and wrote up the day’s log.”

Trees along the river provided habitat for orioles and other species. Since the rain had subsided, we decided to see what might come out and begin feeding. Soon, we not only saw an Altamira Oriole, but found Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus) and the yellow and black tropical species, Audubon’s Oriole (Icterus graduacauda), formerly known as Black-headed Oriole. Three species of orioles on a backdrop of lush green subtropical foliage, it was magnificent.

Along the dirt road below the dam, the mix of scrubland and subtropical riparian forest made for excellent birding. We not only found a soaring Hook-billed Kite, one of the target birds for the trip, but we had good looks at both a Great Horned Owl, then a Barn Owl (Tyto alba) that we flushed from the bare ground in openings among the vegetation as we walked the through. Both had probably pounced on some sort of small prey species prior to our arrival. Because there are seldom crows or ravens to bother them, owls here are more active during than day than they are elsewhere. The subject of this afternoon’s intensive search, the elusive and diminutive Ferruginous Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium brasilianum), is routinely diurnal. Other sightings on our two walks included Turkey Vulture, Black Vulture, White-tailed Kite, Northern Bobwhite, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Golden-fronted Woodpecker, Ladder-backed Woodpecker, Couch’s Kingbird, Brown-crested Flycatcher, Green Jay, Black-crested Titmouse, Mockingbird, Long-billed Thrasher, Great-tailed Grackle, Bronzed Cowbird, Northern Cardinal, and Painted Bunting.

The day finished as so many others had earlier during the trip—with insect-hunting Common Nighthawks calling from the skies around our campsite.

Back in late May of 1983, four members of the Lancaster County Bird Club—Russ Markert, Harold Morrrin, Steve Santner, and your editor—embarked on an energetic trip to find, observe, and photograph birds in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. What follows is a daily account of that two-week-long expedition. Notes logged by Markert some four decades ago are quoted in italics. The images are scans of 35 mm color slide photographs taken along the way by your editor.

DAY SIX—May 26, 1983

“Bentsen State Park — Texas”

“Arose at 7:30. Birded the park and watched for the reported Roadside Hawk. No luck. A Roadrunner and Kiskadee was a welcome addition to our list.”