Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

What was the attraction that prompted dozens of birders to hike more than a mile to a secluded field edge along the Northwest Lancaster County River Trail on this last full day of autumn? It must be something good.

Indeed it was. A Western Flycatcher (Empidonax difficilis), first discovered late last week, has weathered the coastal storm that in recent days pummeled the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed with several inches of rain and blustery winds. Western Flycatchers nest in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Coast regions of North America. They spend their winters in Mexico. There are several records of these tiny passerines in our area during December. The first, a bird found in an area known as Tanglewood during the Southern Lancaster County Christmas Bird Count (CBC) on December 16, 1990, was well documented—photographs were taken and its call was tape recorded. It constituted the first record of a member of the Western Flycatcher’s “Pacific-slope” subspecies group ever seen east of the Mississippi River. It was reported through December 26, 1990. The Tanglewood flycatcher and a bird sighted years later on a subsequent “Solanco CBC” were both found inhabiting wooded thickets in the shelter of a ravine created by one of the Susquehanna’s small tributaries.

How long will this wandering rarity remain along the river trail? For added sustenance, sunny days throughout the coming winter offer ever-increasing chances of stonefly hatches on the adjacent river, particularly in the vicinity of the stone bridge piers. But ultimately, the severity of the weather and the bird’s response to it will determine its destiny.

As the autumn raptor migration draws to a close in the Lower Susquehanna Valley Watershed, observers at the Second Mountain Hawk Watch in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, were today treated to a flight of both Bald and Golden Eagles. Gliding on updrafts created by a brisk northwest breeze striking the slope of the ridge, seven of the former and three of the latter species were seen threading their way through numerous bands of snow as they made their way southwest toward favorable wintering grounds.

The best and final bird of the day, and possibly one of the highlights of the season at this counting station, was a “Barthelemyi Golden Eagle”, a rare Golden Eagle variant with conspicuous shoulder epaulets created by white scapular feathers.

Today’s rarity is the second record of a “Barthelemyi Golden Eagle” at Second Mountain Hawk Watch—the first occurring on October 21, 2017.

SOURCES

Spofford, W. R. 1961. “White Epaulettes in Some Appalachian Golden Eagles”. Prothonotary. 27: 99.

While trimming the trees and shrubs in the susquehannawildlife.net garden, it didn’t seem particularly unusual to hear the resident Carolina Chickadees and Carolina Wrens scolding our every move. But after a while, their persistence did seem a bit out of the ordinary, so we took a little break to have a look around…

Here at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, we are visited by Cooper’s Hawks for several days during the late fall and winter each year. The small birds that visit our feeders have plenty of trees, shrubs, vines, and other natural cover in which to hide from raptors and other native predators. We don’t create unnatural concentrations of birds by dumping food all over the place. We try to keep our small birds healthy by sparingly offering fresh seed and other provisions in clean receptacles to provide a supplement to the seeds, fruits, insects, and other foods that occur naturally in the garden. With only a few vulnerable small birds around, the Cooper’s Hawks visit just long enough to cull out our weakest individuals before moving elsewhere. While they’re in our garden, they too are our welcomed guests.

A glimpse of the rowdy guests crowding the Thanksgiving Day dinner table at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters…

As the annual autumn songbird migration begins to reach its end, native sparrows can be found concentrating in fallow fields, early successional thickets, and brushy margins along forest edges throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Visit native sparrow habitat during mid-to-late November and you have a good chance of seeing these species and more…

If you’re lucky enough to live where non-native House Sparrows won’t overrun your bird feeders, you can offer white millet as a supplement to the wild foods these beautiful sparrows might find in your garden sanctuary. Give it a try!

Recently, we found these Chestnut Oak acorns setting roots into the leaf litter to secure their place among the plants that will turn the forest understory green in the spring. Individual acorns that germinate soon after falling to the ground in autumn may avoid becoming food for squirrels, turkeys, deer, and other wildlife, thus increasing their chances of surviving to later become adult trees able to produce acorns that pass this quick-development trait to yet another generation of oaks.

Colder temperatures and gusty northwest winds are prompting our largest migratory raptors to continue their southward movements. Here are some of the birds seen earlier today riding updrafts of air currents along one of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s numerous ridges.

As winter begins clawing at the door, now is great time to visit a hawk watch near you to see these late-season specialties. Remember to dress in layers and to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page. Hawkwatcher’s Helper is your guide to regional hawk watching locations and raptor identification. Be sure to check it out. And remember, it’s cold on top of those ridges, so don’t forget your hat, your gloves, and your chap stick!

Only fools mess around with bees, wasps, and hornets as they collect nectar and go about their business while visiting flowering plants. Relentlessly curious predators and other trouble makers quickly learn that patterns of white, yellow, or orange contrasting with black are a warning that the pain and anguish of being zapped with a venomous sting awaits those who throw caution to the wind. Through the process of natural selection, many venomous and poisonous animals have developed conspicuously bright or contrasting color schemes to deter would-be predators and molesters from making such a big mistake.

Visual warnings enhance the effectiveness of the defensive measures possessed by venomous, poisonous, and distasteful creatures. Aggressors learn to associate the presence of these color patterns with the experience of pain and discomfort. Thereafter, they keep their distance to avoid any trouble. In return, the potential victims of this unsolicited aggression escape injury and retain their defenses for use against yet-to-be-enlightened pursuers. Thanks to their threatening appearance, the chances of survival are increased for these would-be victims without the need to risk death or injury while deploying their venomous stingers, poisonous compounds, or other defensive measures.

One shouldn’t be surprised to learn that over time, as these aforementioned venomous, poisonous, and foul-tasting critters developed their patterns of warning colors, there were numerous harmless animals living within close association with these species that, through the process of natural selection, acquired nearly identical color patterns for their own protection from predators. This form of defensive impersonation is known as Batesian mimicry.

Let’s take a look at some examples of Batesian mimicry right here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Suppose for a moment that you were a fly. As you might expect, you would have plenty to fear while you spend your day visiting flowers in search of energy-rich nectar—hundreds of hungry birds and other animals want to eat you.

If you were a fly and you were headed out and about to call upon numerous nectar-producing flowers so you could round up some sweet treats, wouldn’t you feel a whole lot safer if you looked like those venomous bees, wasps, and hornets in your neighborhood? Wouldn’t it be a whole lot more fun to look scary—so scary that would-be aggressors fear that you might sting them if they gave you any trouble?

Suppose Mother Nature and Father Time dressed you up to look like a bee or a wasp instead of a helpless fly? Then maybe you could go out and collect sweets without always worrying about the bullies and the brutes, just like these flies of the lower Susquehanna do…

FLOWER FLIES/HOVER FLIES

TACHINID FLIES

BEE FLIES

So let’s review. If you’re a poor defenseless fly and you want to get your fair share of sweets without being gobbled up by the beasts, then you’ve got to masquerade like a strongly armed member of a social colony—like a bee, wasp, or hornet. Now look scary and go get your treats. HAPPY HALLOWEEN!

Where should you go this weekend to see vibrantly colored foliage in our region? Where are there eye-popping displays of reds, oranges, yellows, and greens without so much brown and gray? The answer is Michaux State Forest on South Mountain in Adams, Cumberland, and Franklin Counties.

South Mountain is the northern extension of the Blue Ridge Section of the Ridge and Valley Province in Pennsylvania. Michaux State Forest includes much of the wooded land on South Mountain. Within or adjacent to its borders are located four state parks: King’s Gap Environmental Education Center, Pine Grove Furnace State Park, Caledonia State Park, and Mont Alto State Park. The vast network of trails on these state lands includes the Appalachian Trail, which remains in the mountainous Blue Ridge Section all the way to its southern terminus in Georgia.

If you want a closeup look at the many species of trees found in Michaux State Forest, and you want them to be labeled so you know what they are, a stop at the Pennsylvania State University’s Mont Alto arboretum is a must. Located next door to Mont Alto State Park along PA 233, the Arboretum at Penn State Mont Alto covers the entire campus. Planting began on Arbor Day in 1905 shortly after establishment of the Pennsylvania State Forest Academy at the site in 1903. Back then, the state’s “forests” were in the process of regeneration after nineteenth-century clear cutting. These harvests balded the landscape and left behind the combustible waste which fueled the frequent wildfires that plagued reforestation efforts for more than half a century. The academy educated future foresters on the skills needed to regrow and manage the state’s woodlands.

Online resources can help you plan your visit to the Arboretum at Penn State Mont Alto. More than 800 trees on the campus are numbered with small blue tags. The “List of arboretum trees by Tag Number” can be downloaded to tell you the species or variety of each. The interactive map provides the locations of individual trees plotted by tag number while the Grove Map displays the locations of groups of trees on the campus categorized by region of origin. A Founder’s Tree Map will help you find some of the oldest specimens in the collection and a Commemorative Tree Map will help you find dedicated trees. There is also a species list of the common and scientific tree names.

The autumn leaves will be falling fast, so make it a point this weekend to check out the show on South Mountain.

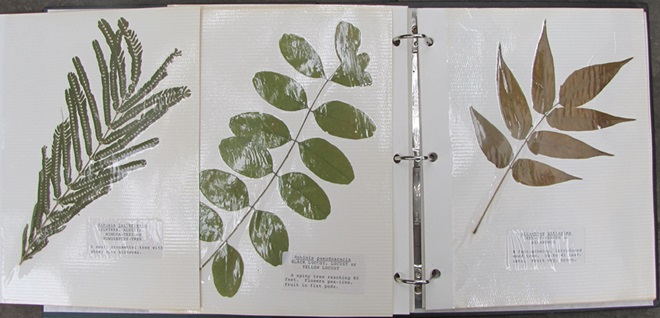

Have you noticed? Foliage throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed has been painted with the brilliant colors of autumn, so now is the time to get out there and have a look. Why not make a collection? You can pick up an inexpensive scrap book or photo album at the craft store to press and label the varieties you find. Uncle Tyler Dyer is already busy adding to the project he assembled last year. You can use his exhibit as a reference for identifying and learning a little bit more about the leaves you find.

With nearly all of the Neotropical migrants including Broad-winged Hawks gone for the year, observers and counters at eastern hawk watches are busy tallying numbers of the more hardy species of diurnal raptors and other birds. The majority of species now coming through will spend the winter months in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the southern United States and Mexico.

Here is a quick look at the raptors seen this week at two regional counting stations: Kiptopeke Hawk Watch near Cape Charles, Virginia, and Second Mountain Hawk Watch at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania.

During coming days, fewer and fewer of these birds will be counted at our local hawk watches. Soon, the larger raptors—Red-tailed Hawks, Red-shouldered Hawks, and Golden Eagles—will be thrilling observers. Cooler weather will bring several flights of these spectacular species. Why not plan a visit to a lookout near you? Click on the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page for site information and a photo guide to identification. See you at the hawk watch!

Say it isn’t so. Does summer really have to go?

Our brightly colored goldfinches are gone for the year. No more Pennsylvania distelfinks glowing like bright-yellow Easter peeps on our feeders. Oh, the birds are still here mind you, but their sunshine-gold feathers are falling away. Because winter time is no time to show off. One must blend in and maintain a low profile to conserve energy and avoid trouble as rough weather arrives. So our American Goldfinches have commenced to molting—shedding their breeding plumes and replacing them with drab earth-tone shades for winter.

Last October 3rd, a late-season Ruby-throated Hummingbird stopped by the garden at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to take shelter from a rainy autumn storm. It was so raw and chilly that we felt compelled to do something we don’t normally do—put out the sugar water feeder to supplement the nectar produced by our fall-flowering plants. After several days of constant visits to the feeder and the flowers, our lingering hummer resumed its southbound journey on October 7th.

Fast forward to this afternoon and what do you know, at least two migrating hummingbirds have stopped by to visit the flowers in our garden. This year, we have an exceptional abundance of blooms on some of their favorite plants. In the ponds, aquatic Pickerelweed is topped with purple spikes and we still have bright orange tubular flowers on one of our Trumpet Vines—a full two to three months later than usual.

Remember, keep those feeders clean and the provisions fresh! You’ll be glad you did.

What’s all this buzz about bees? And what’s a hymanopteran? Well, let’s see.

Hymanoptera—our bees, wasps, hornets and ants—are generally considered to be our most evolved insects. Some form complex social colonies. Others lead solitary lives. Many are essential pollinators of flowering plants, including cultivars that provide food for people around the world. There are those with stingers for disabling prey and defending themselves and their nests. And then there are those without stingers. The predatory species are frequently regarded to be the most significant biological controls of the insects that might otherwise become destructive pests. The vast majority of the Hymanoptera show no aggression toward humans, a demeanor that is seldom reciprocated.

Late summer and early autumn is a critical time for the Hymanoptera. Most species are at their peak of abundance during this time of year, but many of the adult insects face certain death with the coming of freezing weather. Those that will perish are busy, either individually or as members of a colony, creating shelter and gathering food to nourish the larvae that will repopulate the environs with a new generation of adults next year. Without abundant sources of protein and carbohydrates, these efforts can quickly fail. Protein is stored for use by the larval insects upon hatching from their eggs. Because the eggs are typically deposited in a cell directly upon the cache of protein, the larvae can begin feeding and growing immediately. To provide energy for collecting protein and nesting materials, and in some cases excavating nest chambers, Hymanoptera seek out sources of carbohydrates. Species that remain active during cold weather must store up enough of a carbohydrate reserve to make it through the winter. Honey Bees make honey for this purpose. As you are about to see, members of this suborder rely predominately upon pollen or insect prey for protein, and upon nectar and/or honeydew for carbohydrates.

We’ve assembled here a collection of images and some short commentary describing nearly two dozen kinds of Hymanoptera found in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the majority photographed as they busily collected provisions during recent weeks. Let’s see what some of these fascinating hymanopterans are up to…

SOLITARY WASPS

CUCKOO WASPS

SWEAT BEES

LEAFCUTTER AND MASON BEES

BUMBLE BEES, CARPENTER BEES, HONEY BEES, AND DIGGER BEES

SCOLIID WASPS

PAPER WASPS

YELLOWJACKETS AND HORNETS

POTTER WASPS

ANTS

We hope this brief but fascinating look at some of our more common bees, wasps, hornets, and ants has provided the reader with an appreciation for the complexity with which their food webs and ecology have developed over time. It should be no great mystery why bees and other insects, particularly native species, are becoming scarce or absent in areas of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where the landscape is paved, hyper-cultivated, sprayed, mowed, and devoid of native vegetation, particularly nectar-producing plants. Late-summer and autumn can be an especially difficult time for hymanopterans seeking the sources of proteins and carbohydrates needed to complete preparations for next year’s generations of these valuable insects. An absence of these staples during this critical time of year quickly diminishes the diversity of species and begins to tear at the fabric of the food web. This degradation of a regional ecosystem can have unforeseen impacts that become increasingly widespread and in many cases permanent.

Editor’s Note: No bees, wasp, hornets, or ants were harmed during this production. Neither was the editor swarmed, attacked, or stung. Remember, don’t panic, just observe.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

(If you’re interested in insects, get this book!)

Tropical Storm Ophelia has put the brakes on a bustling southbound exodus of the season’s final waves of Neotropical migrants. Winds from easterly directions have now beset the Mid-Atlantic States with gloomy skies, chilly temperatures, and periods of rain for an entire week. These conditions, which are less than favorable for undertaking flights of any significant distance, have compelled many birds to remain in place—grounded to conserve energy.

Of the birds on layover, perhaps the most interesting find has been a western raptor that occurs only on rare occasions among the groups of Broad-winged Hawks seen at hawk watches each fall—a Swainson’s Hawk. Discovered as Tropical Storm Ophelia approached on September 21st, this juvenile bird has found refuge in coal country on a small farm in a picturesque valley between converging ridges in southern Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. Swainson’s Hawks are a gregarious species, often spending time outside of the nesting season in the company of others of their kind. Like Broad-winged Hawks, they frequently assemble into large groups while migrating.

Swainson’s Hawks nest in the grasslands, prairies, and deserts of western North America. Their autumn migration to wintering grounds in Argentina covers a distance of up to 6,000 miles. Among raptors, such mileage is outdone only by the Tundra Peregrine Falcon.

During the nesting cycle, Swainson’s Hawks consume primarily small vertebrates, mostly mice and other small rodents. But during the remainder of the year, they feed almost exclusively on grasshoppers. To provide enough energy to fuel their migrations, they must find and devour these insects by the hundreds. Not surprisingly, the Swainson’s Hawk is sometimes known as the Grasshopper Hawk or Locust Hawk, particularly in the areas of South America where they are common.

So just how far will our wayward Swainson’s Hawk have to travel to get back on track? Small numbers of Swainson’s Hawks pass the winter in southern Florida each year and still others are found in and near the scrublands of the Lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas and Mexico. But the vast majority of these birds make the trip all the way to the southern half of South America and the farmlands and savannas of Argentina—where our winter is their summer. The best bet for this bird would be to get hooked up with some of the season’s last Broad-winged Hawks when they start flying in coming days, then join them as they head toward Houston, Texas, to make the southward turn down the coast of the Gulf of Mexico into Central America and Amazonia. Then again, it may need to find its own way to warmer climes. Upon reaching at least the Gulf Coastal Plain, our visitor stands a much better chance of surviving the winter.

They look amazingly similar to the green leaves on a deciduous tree. During the late summer and autumn, they spend their time as adults in the cover of the forest canopy. They prefer to run and hop rather than fly. But despite their discretion, you’re not likely to miss the Common True Katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia).

Take a listen and you may hear the male’s nocturnal calls filling the treetops of woodlands and shady neighborhoods throughout the lower Susquehanna valley right now. The loud, raspy “ka-ty-did, she-did, she-didn’t” is reliably answered by other nearby males as competition for willing females reaches a frenzy. In mature forests where populations are dense, this rowdy chorus can reach a remarkable volume.

The Common True Katydid’s song is like a soundtrack for the oft times melancholy mood of autumn. As the days shorten and a chill fills the air, the rate of the Common True Katydid’s call becomes slower and its tone deeper in response to the falling temperatures. Males continue forcing a sluggish call until freezing conditions finally bring about their demise. Another generation and another season gone.

Grasshoppers are perhaps best known for the occasions throughout history when an enormous congregation of these insects—a “plague of locusts”—would assemble and rove a region to feed. These swarms, which sometimes covered tens of thousands of square miles or more, often decimated crops, darkened the sky, and, on occasion, resulted in catastrophic famine among human settlements in various parts of the world.

The largest “plague of locusts” in the United States occurred during the mid-1870s in the Great Plains. The Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus), a grasshopper of prairies in the American west, had a range that extended east into New England, possibly settling there on lands cleared for farming. Rocky Mountain Locusts, aside from their native habitat on grasslands, apparently thrived on fields planted with warm-season crops. Like most grasshoppers, they fed and developed most vigorously during periods of dry, hot weather. With plenty of vegetative matter to consume during periods of scorching temperatures, the stage was set for populations of these insects to explode in agricultural areas, then take wing in search of more forage. Plagues struck parts of northern New England as early as the mid-1700s and were numerous in various states in the Great Plains through the middle of the 1800s. The big ones hit between 1873 and 1877 when swarms numbering as many as trillions of grasshoppers did $200 million in crop damage and caused a famine so severe that many farmers abandoned the westward migration. To prevent recurrent outbreaks of locust plagues and famine, experts suggested planting more cool-season grains like winter wheat, a crop which could mature and be harvested before the grasshoppers had a chance to cause any significant damage. In the years that followed, and as prairies gave way to the expansive agricultural lands that presently cover most of the Rocky Mountain Locust’s former range, the grasshopper began to disappear. By the early years of the twentieth century, the species was extinct. No one was quite certain why, and the precise cause is still a topic of debate to this day. Conversion of nearly all of its native habitat to cropland and grazing acreage seems to be the most likely culprit.

In the Mid-Atlantic States, the mosaic of the landscape—farmland interspersed with a mix of forest and disturbed urban/suburban lots—prevents grasshoppers from reaching the densities from which swarms arise. In the years since the implementation of “Green Revolution” farming practices, numbers of grasshoppers in our region have declined. Systemic insecticides including neonicotinoids keep grasshoppers and other insects from munching on warm-season crops like corn and soybeans. And herbicides including 2,4-D (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) have, in effect, become the equivalent of insecticides, eliminating broadleaf food plants from the pasturelands and hayfields where grasshoppers once fed and reproduced in abundance. As a result, few of the approximately three dozen species of grasshoppers with ranges that include the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are common here. Those that still thrive are largely adapted to roadsides, waste ground, and small clearings where native and some non-native plants make up their diet.

Here’s a look at four species of grasshoppers you’re likely to find in disturbed habitats throughout our region. Each remains common in relatively pesticide-free spaces with stands of dense grasses and broadleaf plants nearby.

CAROLINA GRASSHOPPER

Dissosteira carolina

DIFFERENTIAL GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus differentialis

TWO-STRIPED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus bivittatus

RED-LEGGED GRASSHOPPER

Melanoplus femurrubrum

Protein-rich grasshoppers are an important late-summer, early-fall food source for birds. The absence of these insects has forced many species of breeding birds to abandon farmland or, in some cases, disappear altogether.

During the past two weeks, over 150 American Flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) have been reported in the eastern half of the United States, well north of their usual range—northern South America; Cuba, the Bahamas, and other Caribbean Islands; and the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. They are also found on the Galapagos Islands. Prior to being extirpated by hunting during the early years of the twentieth century, American Flamingos nested in the Everglades of Florida as well.

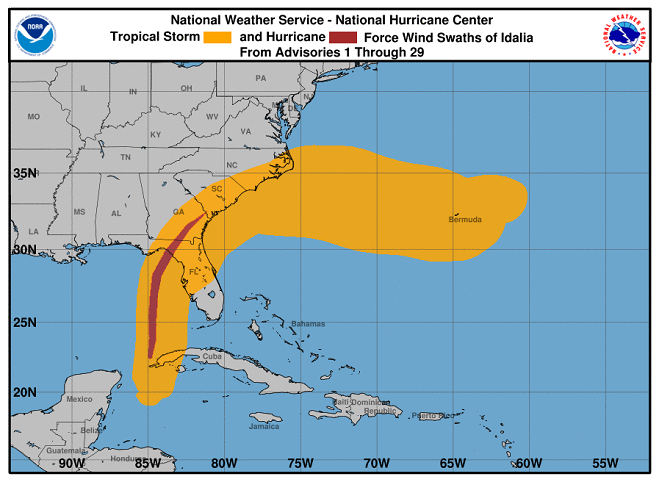

The recent influx of these tropical vagrants into the eastern states is attributed to Hurricane Idalia, a storm that formed in the midst of flamingo territory during the final week of August. Idalia got its start over tropical waters off Yucatan before progressing north through the Gulf of Mexico off Cuba to make landfall in the “Big Bend” area of Florida.

Birds of warm water seas regularly become entangled within tropical storms and hurricanes. In most cases, it’s oceanic seabirds including petrels, shearwaters, terns, and gulls that seek refuge from turbulent conditions by remaining inside the storm’s eye or within the margins of the rotating bands. The duration of the experience and the fitness of each individual bird may determine just how many survive such an ordeal. As a storm makes landfall, the survivors put down on inland bodies of water, often in unexpected places hundreds of miles from the nearest coastline. Some may linger in these far-flung areas to feed and gain strength before finding their way down rivers back to sea.

For birds like American Flamingos, which don’t spend a large portion of their lives on the wing over vast oceanic waters, becoming entangled in a tropical weather system can easily be a life-ending event. American Flamingos, despite their size and lanky appearance, are quite agile fliers. When necessary, some populations travel significant distances in search of new food sources. Some closely related migratory species of flamingos have been recorded at altitudes exceeding 10,000 feet. But becoming trapped in a hurricane for an extended period of time could easily erode the endurance of even the strongest of fliers. And once out over open water, there’s nowhere for a flamingo to come down for a rest.

It appears probable that, during the final week of August, hundreds of American Flamingos did find themselves drawn away from their familiar tidal flats and salty lagoons to be swept into the spinning clouds and gusty downpours of Hurricane Idalia as it churned off the Yucatan coast. Despite the dangers, more than 150 of them completed a journey within its clutches to cross the Gulf of Mexico and land in the Eastern United States.

Amy Davis in a report for the American Birding Association compiled a list of American Flamingo sightings from the days following the landfall of Hurricane Idalia. We’ve plotted those sightings on a satellite image of the storm.

The majority of the flamingos that survived this harrowing trip found a place to put down along the coast. But as the reader will notice, a significant number of the sightings were outside the path of the storm in areas not reached by even the outermost bands of clouds. Flamingos in Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky/Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania were found at inland bodies of water, most on the days immediately following the storm’s landfall. The lone exception, the Pennsylvania birds, were discovered a week after landfall (but may have been there days longer). How and why did these birds find their way so far inland at places so distant from the storm…and home? And how did they get there so quickly? The counterclockwise rotation of the hurricane wouldn’t slingshot them in that direction, would it?

Let’s have a look at the surface map showing us the weather in the states outside the direct influence of Hurricane Idalia during the storm’s landfall on August 30, 2023…

Now check out this satellite view of the storm during the hours following landfall…

Click the image above to play a GIF animation of GOES-16 satellite photos showing Idalia after landfall and the strong “flamingo highway” winds between the fronts. (It’s a big file, so give it a little time to load.) You’ll also note the ferocious lightning associated with both Huricane Idalia and Hurricane Franklin.

Did the inland flamingos catch a ride on these stiff “flamingo highway” winds? If not, they may have had a little help from a high pressure ridge that became established over the southern Appalachians as Idalia crept out to sea. The clockwise rotation of this ridge kept a similar flow over the “flamingo highway” for much of the four days that followed.

For vagrant birds including those carried away to distant lands by hurricanes and other storms, the challenges of finding food and avoiding hazards including disease, unfamiliar predators, and extreme weather can be a matter of life and death. For American Flamingos now loafing and feeding in the Eastern United States outside Florida, the hardest part of their journey is yet to come. They need to find their way back south to suitable tropical habitat before cold weather sets in. The perils are many. Theirs is not an enviable predicament.

To pass the afternoon, we sat quietly along the edge of a pond created recently by North American Beavers (Castor canadensis). They first constructed their dam on this small stream about five years ago. Since then, a flourishing wetland has become established. Have a look.

Isn’t that amazing? North American Beavers build and maintain what human engineers struggle to master—dams and ponds that reduce pollution, allow fish passage, and support self-sustaining ecosystems. Want to clean up the streams and floodplains of your local watershed? Let the beavers do the job!