Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

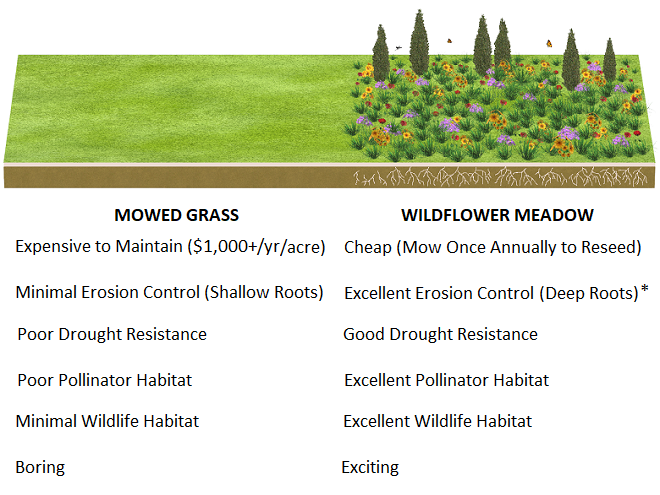

This month, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (I.U.C.N.) added the Migratory Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) to its “Red List of Threatened Species”, classifying it as endangered. Perhaps there is no better time than the present to have a look at the virtues of replacing areas of mowed and manicured grass with a wildflower garden or meadow that provides essential breeding and feeding habitat for Monarchs and hundreds of other species of animals.

If you’re not quite sure about finally breaking the ties that bind you to the cult of lawn manicuring, then compare the attributes of a parcel maintained as mowed grass with those of a space planted as a wildflower garden or meadow. In our example we’ve mixed native warm season grasses with the wildflowers and thrown in a couple of Eastern Red Cedars to create a more authentic early successional habitat.

Still not ready to take the leap. Think about this: once established, the wildflower planting can be maintained without the use of herbicides or insecticides. There’ll be no pesticide residues leaching into the soil or running off during downpours. Yes friends, it doesn’t matter whether you’re using a private well or a community system, a wildflower meadow is an asset to your water supply. Not only is it free of man-made chemicals, but it also provides stormwater retention to recharge the aquifer by holding precipitation on site and guiding it into the ground. Mowed grass on the other hand, particularly when situated on steep slopes or when the ground is frozen or dry, does little to stop or slow the sheet runoff that floods and pollutes streams during heavy rains.

What if I told you that for less than fifty bucks, you could start a wildflower garden covering 1,000 square feet of space? That’s a nice plot 25′ x 40′ or a strip 10′ wide and 100′ long along a driveway, field margin, roadside, property line, swale, or stream. All you need to do is cast seed evenly across bare soil in a sunny location and you’ll soon have a spectacular wildflower garden. Here at the susquehannawildllife.net headquarters we don’t have that much space, so we just cast the seed along the margins of the driveway and around established trees and shrubs. Look what we get for pennies a plant…

Here’s a closer look…

All this and best of all, we never need to mow.

Around the garden, we’ve used a northeast wildflower mix from American Meadows. It’s a blend of annuals and perennials that’s easy to grow. On their website, you’ll find seeds for individual species as well as mixes and instructions for planting and maintaining your wildflower garden. They even have a mix specifically formulated for hummingbirds and butterflies.

Nothing does more to promote the spread and abundance of non-native plants, including invasive species, than repetitive mowing. One of the big advantages of planting a wildflower garden or meadow is the opportunity to promote the growth of a community of diverse native plants on your property. A single mowing is done only during the dormant season to reseed annuals and to maintain the meadow in an early successional stage—preventing reversion to forest.

For wildflower mixes containing native species, including ecotypes from locations in and near the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, nobody beats Ernst Conservation Seeds of Meadville, Pennsylvania. Their selection of grass and wildflower seed mixes could keep you planting new projects for a lifetime. They craft blends for specific regions, states, physiographic provinces, habitats, soils, and uses. Check out these examples of some of the scores of mixes offered at Ernst Conservation Seeds…

We’ve used their “Showy Northeast Native Wildflower and Grass Mix” on streambank renewal projects with great success. For Monarchs, we really recommend the “Butterfly and Hummingbird Garden Mix”. It includes many of the species pictured above plus “Fort Indiantown Gap” Little Bluestem, a warm-season grass native to Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, and milkweeds (Asclepias), which are not included in their northeast native wildflower blends. More than a dozen of the flowers and grasses currently included in this mix are derived from Pennsylvania ecotypes, so you can expect them to thrive in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

In addition to the milkweeds, you’ll find these attractive plants included in Ernst Conservation Seed’s “Butterfly and Hummingbird Garden Mix”, as well as in some of their other blends.

Why not give the Monarchs and other wildlife living around you a little help? Plant a wildflower garden or meadow. It’s so easy, a child can do it.

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

On a snowy winter day, it sure is nice to see some new visitors at a backyard feeding station. Here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, American Robins have arrived to partake of the offerings.

For this flock of robins, which numbered in excess of 150 individuals, the contents of this tray were a mere garnish to the meal that would sustain them through 72 hours of stormy weather. The main course was the supply of ripe berries on shrubs and trees in the headquarters garden.

Their first choice—the bright red fruits of the Common Winterberry.

After cleaning off the winterberry shrubs, other fruits became part of the three-day-long feast.

Wouldn’t it be great to see these colorful birds in your garden each winter? You can, you know. Won’t you consider adding plantings of native trees and shrubs to your property this spring? Here at the susquehannawildlife.com headquarters we mow no lawn; the lawn is gone. Mixing evergreens and fruit-producing shrubs with native warm-season grasses and flowering plants has created a wildlife oasis absent of that dirty habit of mowing and blowing.

You can find many of the plants seen here at your local garden center. Take a chunk out of your lawn by paying them a visit this spring.

Want a great deal? Many of the County Conservation District offices in the lower Susquehanna region are having their annual spring tree sales right now. Over the years, we obtained many of our evergreens and berry-producing shrubs from these sales for less than two dollars each. At that price you can blanket that stream bank or wet spot in the yard with winterberries and mow it no more! The deadlines for orders are quickly approaching, so act today—literally, act today. Visit your County Conservation District’s website for details including selections, prices, order deadlines, and pickup dates and locations.

County Conservation District Tree Sales

Consult each County Conservation District’s Tree Sale web page for ordering info, pickup locations, and changes to these dates and times.

Cumberland County Conservation District Tree Seedling Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Tuesday, March 30, 2021. Pickup 1 P.M. to 5 P.M., Thursday, April 22, 2021, and 8 A.M. to 2 P.M., Friday, April 23, 2021. https://www.ccpa.net/4636/Tree-Seedling-Sale

Lancaster County Conservation District Tree Sale—deadline for prepaid orders (hand-delivered to drop box) 5 P.M., Friday, March 5, 2021. Pickup 8 A.M. to 5 P.M., Thursday, April 15, 2021. https://www.lancasterconservation.org/tree-sale/

Lebanon County Conservation District Tree Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Thursday, March 11, 2021. Pickup 9 A.M. to 6 P.M., Friday, May 7, 2021. https://www.lccd.org/2021-tree-sale/

Perry County Conservation District Tree Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Wednesday, March 24, 2021. Pickup 10 A.M. to 6 P.M., Thursday, April 8, 2021. www.perrycd.org/Documents/2021 Tree Sale Flyer LEGAL SIZE.pdf

York County Conservation District Seedling Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Monday, March 15, 2021. Pickup 10 A.M. to 6 P.M., Thursday, April 15, 2021. https://www.yorkccd.org/events/2021-seedling-sale

Thoughts of October in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed bring to mind scenes of brilliant fall foliage adorning wooded hillsides and stream courses, frosty mornings bringing an end to the growing season, and geese and other birds flying south for the winter.

The autumn migration of birds spans a period equaling nearly half the calendar year. Shorebirds and Neotropical perching birds begin moving through as early as late July, just as daylight hours begin decreasing during the weeks following their peak at summer solstice in late June. During the darkest days of the year, those surrounding winter solstice in late December, the last of the southbound migrants, including some hawks, eagles, waterfowl, and gulls, may still be on the move.

During October, there is a distinct change in the list of species an observer might find migrating through the lower Susquehanna valley. Reduced hours of daylight and plunges in temperatures—particularly frost and freeze events—impact the food sources available to birds. It is during October that we say goodbye to the Neotropical migrants and hello to those more hardy species that spend their winters in temperate climates like ours.

The need for food and cover is critical for the survival of wildlife during the colder months. If you are a property steward, think about providing places for wildlife in the landscape. Mow less. Plant trees, particularly evergreens. Thickets are good—plant or protect fruit-bearing vines and shrubs, and allow herbaceous native plants to flower and produce seed. And if you’re putting out provisions for songbirds, keep the feeders clean. Remember, even small yards and gardens can provide a life-saving oasis for migrating and wintering birds. With a larger parcel of land, you can do even more.

A special message from your local Chinese Mantis (Tenodera sinensis).

Hey you! Yes, you. I pray you’re paying attention to what’s flying around out there, otherwise it’ll all pass you by.

This summer’s hot humid breezes from the south have not only carried swarms of dragonflies into the lower Susquehanna valley, but butterflies too.

So check out these extravagant visitors from south of the Mason-Dixon Line—before my appetite gets the better of me.

There you have it. Get out there and have a look around. These species won’t be active much longer. In just a matter of weeks, our migratory butterflies, including Monarchs, will be heading south and our visiting strays will either follow their lead or risk succumbing to frosty weather.

For more photographs of butterflies, be sure to click the “Butterflies” tab at the top of the page. We’re adding more as we get them.

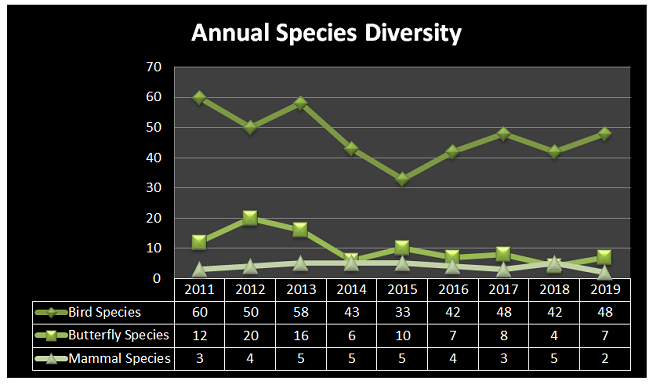

Inside the doorway that leads to your editor’s 3,500 square foot garden hangs a small chalkboard upon which he records the common names of the species of birds that are seen there—or from there—during the year. If he remembers to, he records the date when the species was first seen during that particular year. On New Year’s Day, the results from the freshly ended year are transcribed onto a sheet of notebook paper. On the reverse, the names of butterflies, mammals, and other animals that visited the garden are copied from a second chalkboard that hangs nearby. The piece of paper is then inserted into a folder to join those from previous New Year’s Days. The folder then gets placed back into the editor’s desk drawer beneath a circular saw blade and an old scratched up set of sunglasses—so that he knows exactly where to find it if he wishes to.

A quick glance at this year’s list calls to mind a few recollections.

Before putting the folder back into the drawer for another year, the editor decided to count up the species totals on each of the sheets and load them into the chart maker in the computer.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

It appears that, at the very least, the garden habitat has been disconnected from the home ranges of many species by fragmentation. His little oasis is now isolated in a landscape that becomes increasingly hostile to native wildlife with each passing year. The paving of more parking areas, the elimination of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous growth from the large number of rental properties in the area, the alteration of the biology of the nearby stream by hand-fed domestic ducks, light pollution, and the outdoor use of pesticides have all contributed to the separation of the editor’s tiny sanctuary from the travel lanes and core habitats of many of the species that formerly visited, fed, or bred there. In 2019, migrants, particularly “fly-overs”, were nearly the only sightings aside from several woodpeckers, invasive House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and hardy Mourning Doves. Even rascally European Starlings became sporadic in occurrence—imagine that! It was the most lackluster year in memory.

If habitat fragmentation were the sole cause for the downward trend in numbers and species, it would be disappointing, but comprehensible. There would be no cause for greater alarm. It would be a matter of cause and effect. But the problem is more widespread.

Although the editor spent a great deal of time in the garden this year, he was also out and about, traveling hundreds of miles per week through lands on both the east and the west shores of the lower Susquehanna. And on each journey, the number of birds seen could be counted on fingers and toes. A decade earlier, there were thousands of birds in these same locations, particularly during the late summer.

In the lower Susquehanna valley, something has drastically reduced the population of birds during breeding season, post-breeding dispersal, and the staging period preceding autumn migration. In much of the region, their late-spring through summer absence was, in 2019, conspicuous. What happened to the tens of thousands of swallows that used to gather on wires along rural roads in August and September before moving south? The groups of dozens of Eastern Kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus) that did their fly-catching from perches in willows alongside meadows and shorelines—where are they?

Several studies published during the autumn of 2019 have documented and/or predicted losses in bird populations in the eastern half of the United States and elsewhere. These studies looked at data samples collected during recent decades to either arrive at conclusions or project future trends. They cite climate change, the feline infestation, and habitat loss/degradation among the factors contributing to alterations in range, migration, and overall numbers.

There’s not much need for analysis to determine if bird numbers have plummeted in certain Lower Susquehanna Watershed habitats during the aforementioned seasons—the birds are gone. None of these studies documented or forecast such an abrupt decline. Is there a mysterious cause for the loss of the valley’s birds? Did they die off? Is there a disease or chemical killing them or inhibiting their reproduction? Is it global warming? Is it Three Mile Island? Is it plastic straws, wind turbines, or vehicle traffic?

The answer might not be so cryptic. It might be right before our eyes. And we’ll explore it during 2020.

In the meantime, Uncle Ty and I going to the Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg. You should go too. They have lots of food there.

It’s sprayed with herbicides. It’s mowed and mangled. It’s ground to shreds with noisy weed-trimmers. It’s scorned and maligned. It’s been targeted for elimination by some governments because it’s undesirable and “noxious”. And it has that four letter word in its name which dooms the fate of any plant that possesses it. It’s the Common Milkweed, and it’s the center of activity in our garden at this time of year. Yep, we said milk-WEED.

Now, you need to understand that our garden is small—less than 2,500 square feet. There is no lawn, and there will be no lawn. We’ll have nothing to do with the lawn nonsense. Those of you who know us, know that the lawn, or anything that looks like lawn, are through.

Anyway, most of the plants in the garden are native species. There are trees, numerous shrubs, some water features with aquatic plants, and filling the sunny margins is a mix of native grassland plants including Common Milkweed. The unusually wet growing season in 2018 has been very kind to these plants. They are still very green and lush. And the animals that rely on them are having a banner year. Have a look…

We’ve planted a variety of native grassland species to help support the milkweed structurally and to provide a more complete habitat for Monarch butterflies and other native insects. This year, these plants are exceptionally colorful for late-August due to the abundance of rain. The warm season grasses shown below are the four primary species found in the American tall-grass prairies and elsewhere.

There was Monarch activity in the garden today like we’ve never seen before—and it revolved around milkweed and the companion plants.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.