Have a look at the effect of the Saharan dust event of 2020 on tropical storm and hurricane development…

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Have a look at the effect of the Saharan dust event of 2020 on tropical storm and hurricane development…

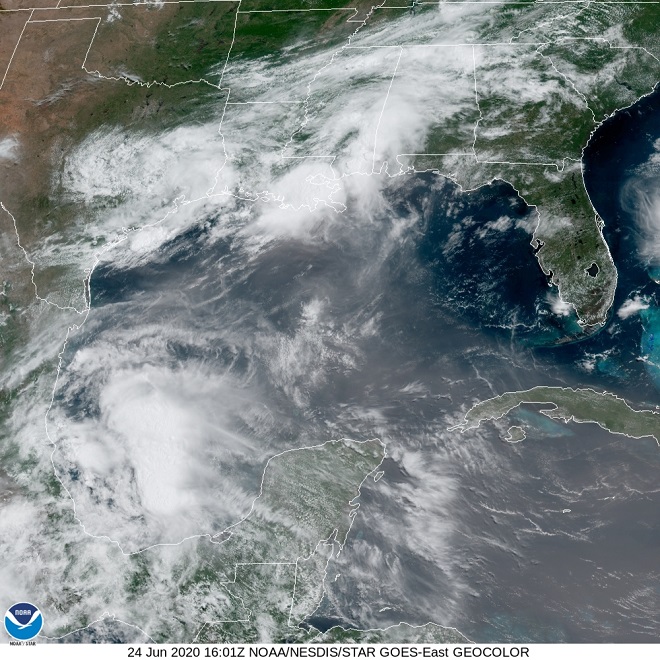

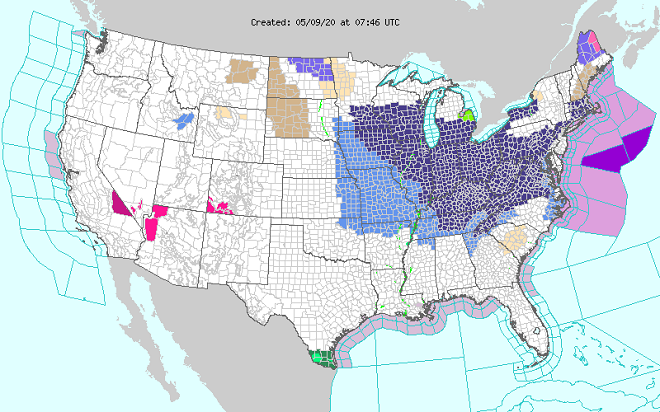

It appears that the Saharan dust cloud has at last wandered our way. The plume is presently advancing across Texas and the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.

Be sure to get outside and have a look at the sunsets and sunrises in the coming days. They just might be a photo-worthy spectacle!

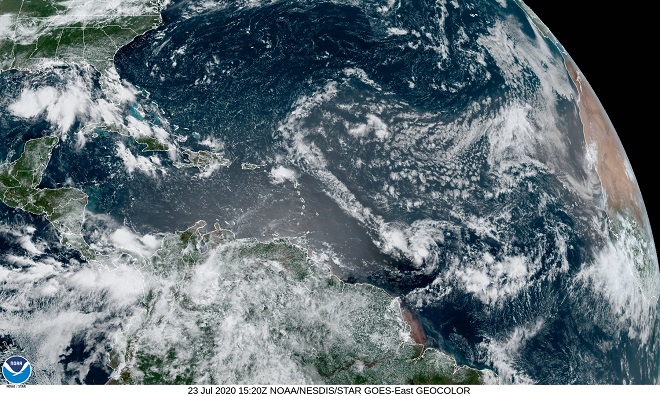

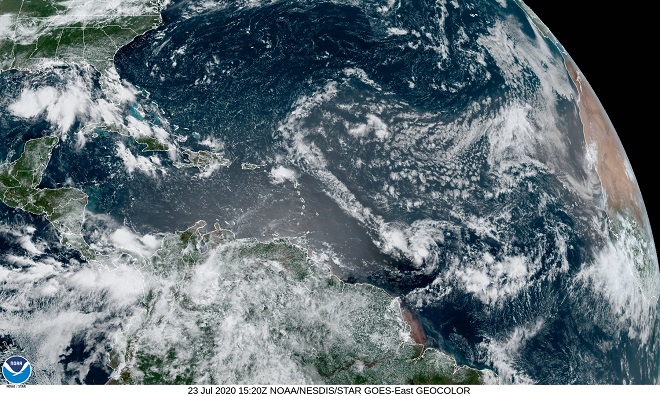

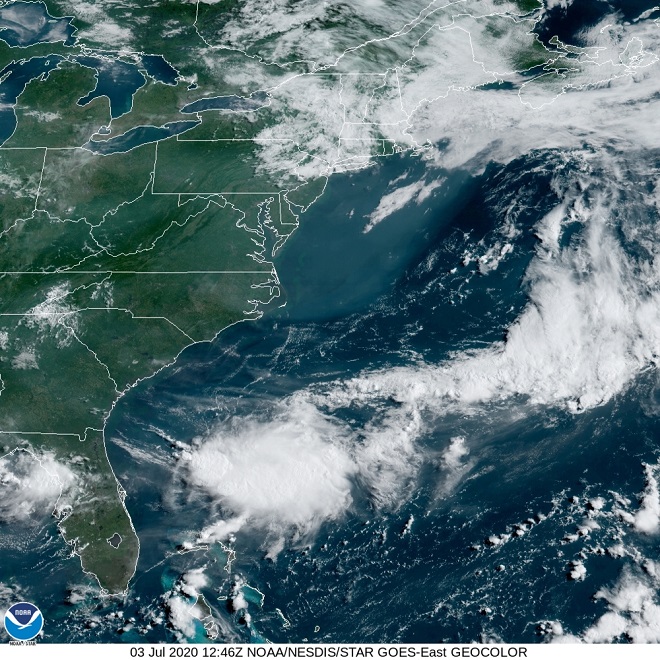

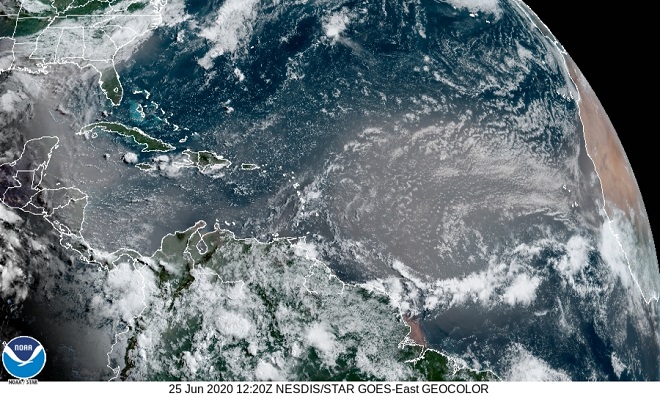

Dust continues to be carried aloft on dry updrafts over the Sahara Desert. The plume is presently stretching for thousands of miles due west across the tropical Atlantic into the Pacific, leaving the United States out of the loop—at least for now.

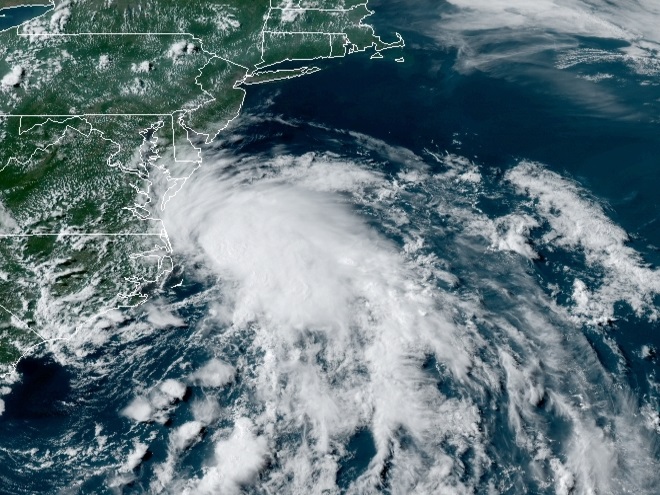

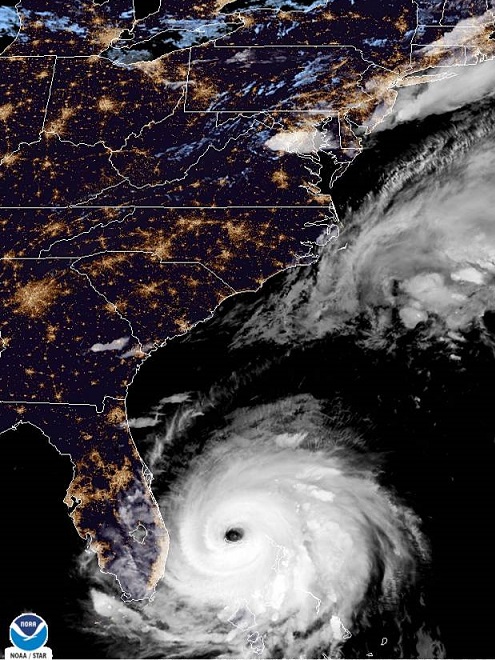

With no dry air to spoil the fun, the warm waters of the Gulf Stream off the coast of North Carolina are spawning some convective clouds in a low pressure system that could become tropical within the next day or so.

Now that the heat and humidity is upon us, why not get out and take a look at the damselflies and dragonflies that inhabit the ponds, wetlands, and waterways of the lower Susquehanna watershed? These flying insects thrive in sultry weather and some species will breed in a body of water as small as a garden pond—as long as it is free of large fish. Check out some of the species found locally by clicking on the “Damselflies and Dragonflies” tab at the top of this page. We’ll be adding more photos and species soon.

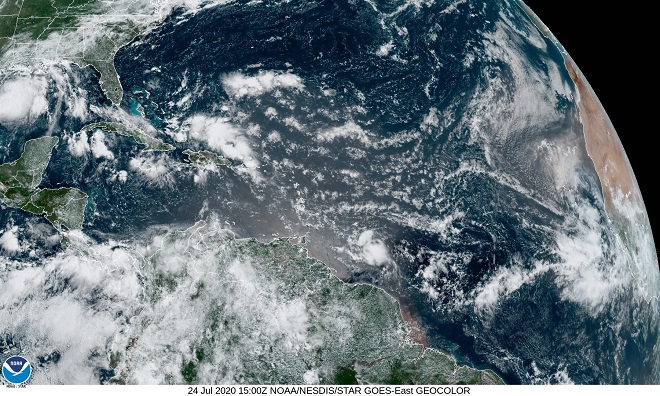

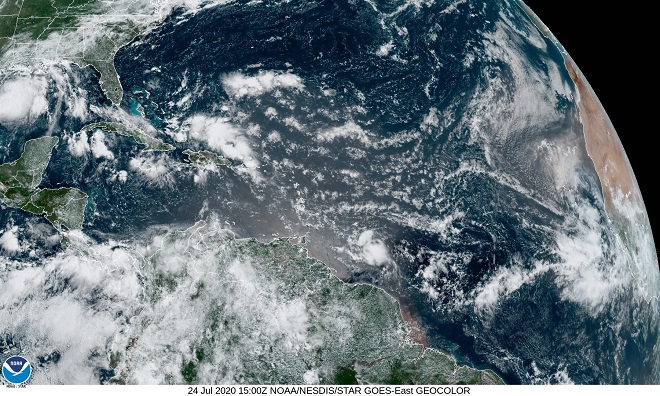

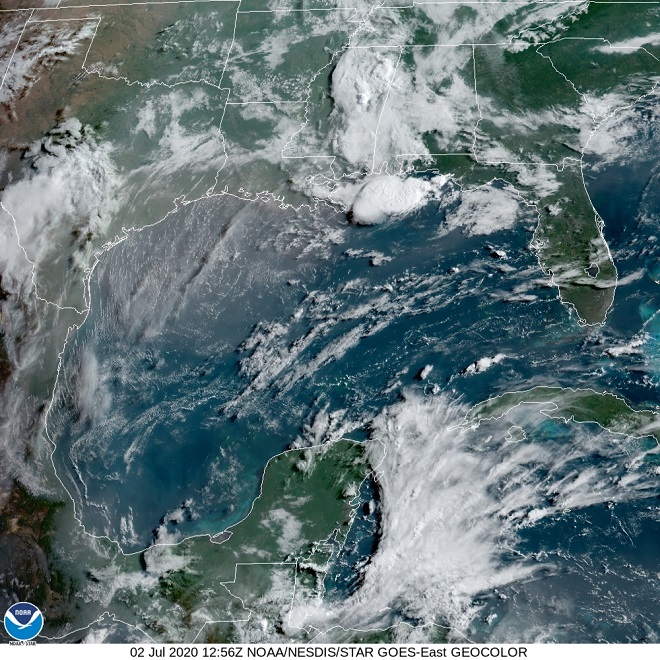

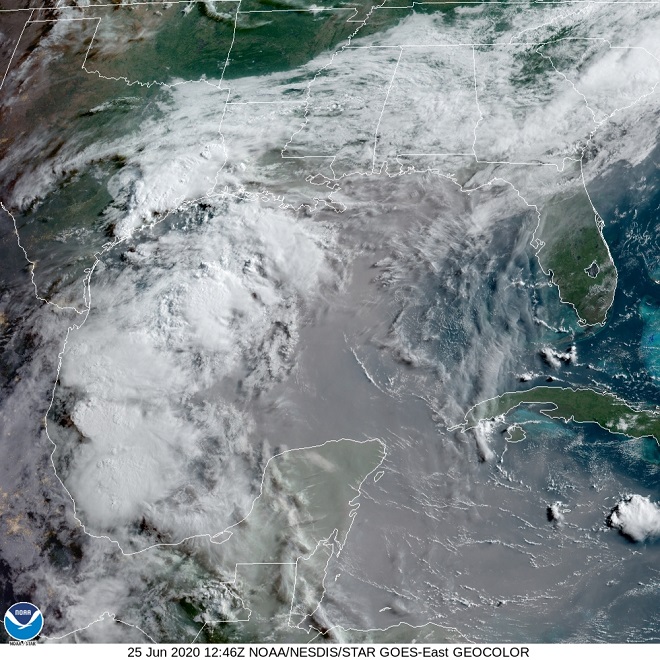

The overcast of Saharan dust that was as close to the Susquehanna valley as the Appalachians of Virginia and West Virginia has, for now, dissipated. This week, the plume of particulates followed a hairpin route originating with the Saharan updrafts, then flowing across the Atlantic and Caribbean only to make a 180-degree turn along the coastal areas of the Gulf of Mexico to return to the Atlantic via Florida, where it then drifted northeast—loosely following the path of the Gulf Stream.

During the last several days, portions of the dust layer have been carried due west across Mexico into the Pacific.

For the Susquehanna region, a low pressure system is in place for Independence Day. In the image below, the cloud of hazy humid air seen blanketing the northeast coast consists of air pollution, pollen, mold spores, “domestic particulates”, condensing water vapor—and little if any red-brown Saharan dust. For the gasoline and gunpowder gang, it’ll be a sticky-hot summer weekend for the celebration of their favorite holiday. Kaboom!

The latest satellite image shows the Saharan dust cloud now covering much of the southern United States including most of West Virginia and the Appalachians of North Carolina and Virginia. Due to the density of the particulate matter, air quality warnings have been issued by the National Weather Service for South Carolina, western North Carolina, and the Atlanta metro area.

As the plume of dust drifts east from the southern United States into the Atlantic…

…yet more can be seen coming west from the African Sahara into the Caribbean Sea. It ain’t over til’ it’s over.

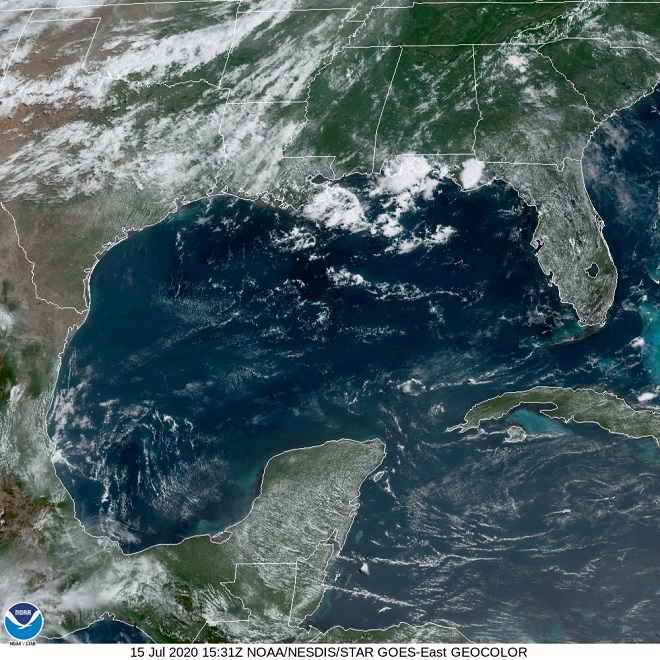

The Saharan dust cloud made its way across the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico to reach the skies above the shores of the United States by mid-day yesterday. There, as seen in the image below, the dusty air mass encountered a storm that caused heavy rains and flooding in Louisiana.

By this morning, the leading edge of the dust cloud encircled the gulf coastline and had spread east across northern Florida into the Atlantic. The latest satellite image (below) shows a dense dry core of the system covering the western Caribbean, the central gulf, and the Yucatan Peninsula.

For the eastern Caribbean, there is a break in the action. But a second wave is on the way.

Start watching the skies. Look for any increase in haze during the coming days. Then too, it might be interesting to compare the sunsets for one evening to the next. Over successive nights, take note of the stars and planets in the night sky. If the Saharan dust reaches the lower Susquehanna region with sufficient density, you may find that only the brightest celestial objects are discernible.

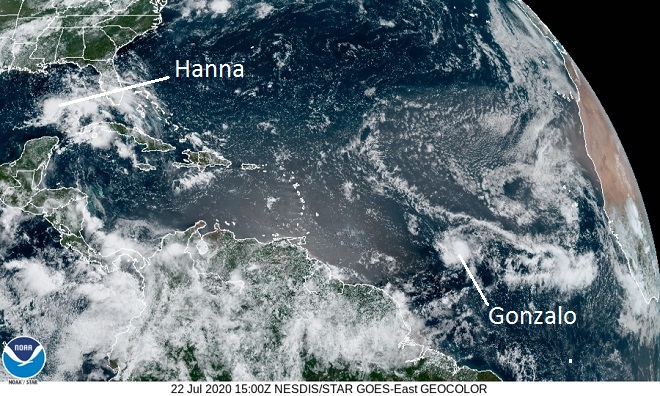

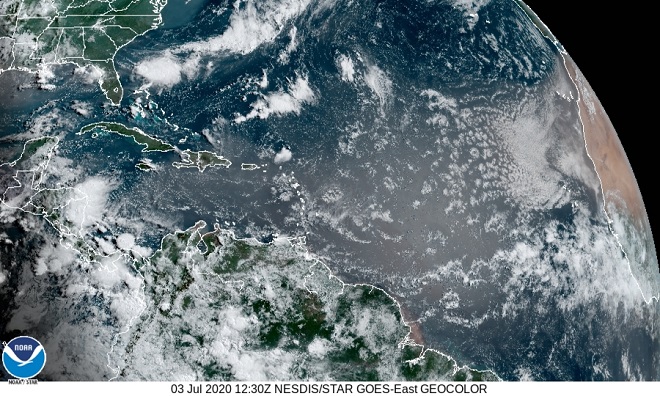

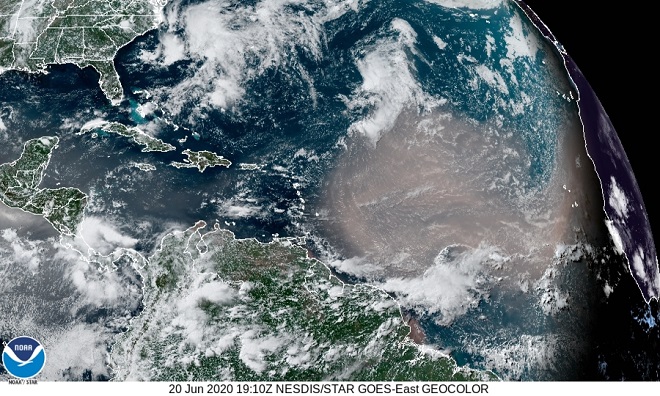

Dust carried aloft by hot dry air over the Sahara Desert continues to stream west into the Caribbean Sea. In this image, a dense band of the airborne particles can be seen passing over the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and the Leeward Islands. North of these islands, note the development of puffy white clouds outside the border of the dust storm. The Saharan air mass appears to be effectively limiting convective cloud development within much of its course. No hurricanes for now.

What is the impact of the Saharan dust cloud on the affected islands? In Puerto Rico, the National Weather Service is forecasting visibility of four to eight miles in widespread haze through at least the next twenty-four hours. For the coming several days, the forecast daily high temperatures are expected to be in the low eighties—several degrees cooler than the normal high eighties and low nineties.

Stay tuned, we’ll keep an eye on the plume as it moves into the Gulf of Mexico.

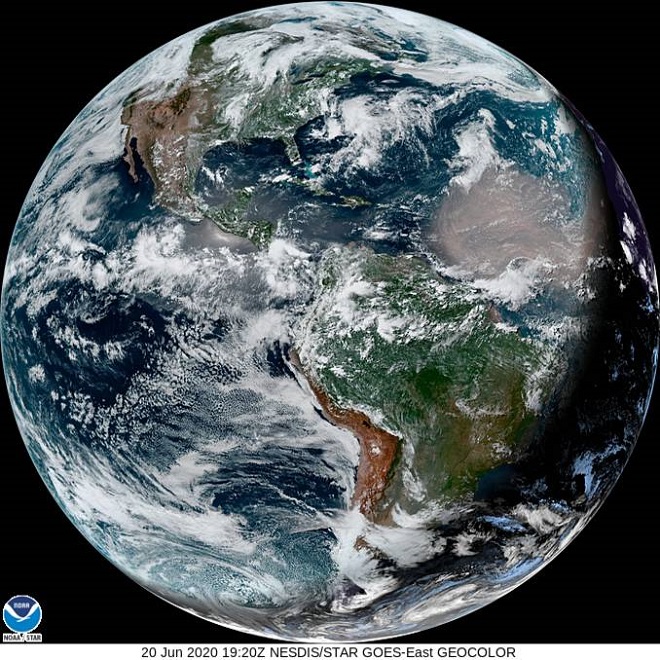

Summer is nigh upon us. With the solstice just hours away, it might be fun to have a look at a satellite view of the earth while the south pole lies plunged into days of endless night, and the north pole suffers none.

In the image above, darkness can be seen engulfing the southern Atlantic Ocean and southernmost Chile. The latter is the longitudinal equivalent of the lower Susquehanna valley. Today, it experiences nightfall more than five hours earlier than we, heralding the first day of our summer, and of their winter.

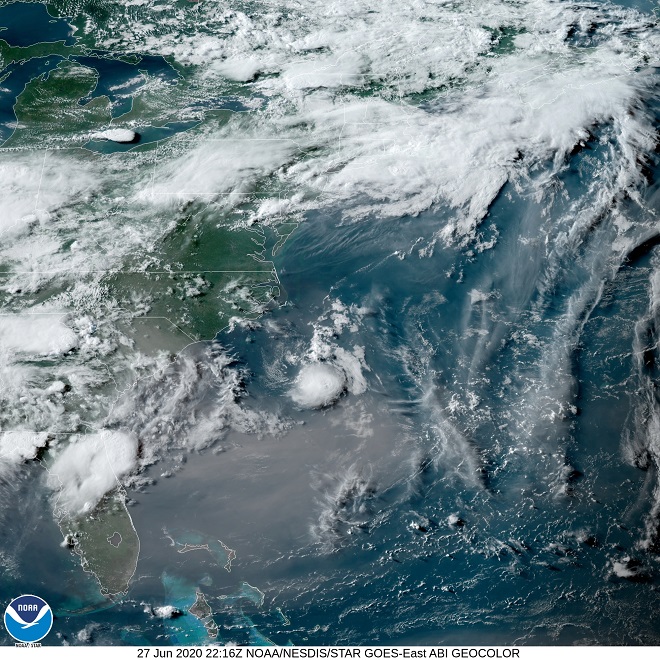

Just to the north of the South American continent, note the enormous tan-colored cloud over the Atlantic. What is that? From whence doth that cloud come?

Closer inspection reveals an enormous plume of dust rising from the Sahara Desert in Africa and drifting west approaching the Leeward Islands of the Caribbean. (In the image above, Africa can be seen outlined in the darkness along the east horizon) Look closely and you’ll notice that the dust is obscuring the white clouds below it, indicating that it has reached altitudes high in the atmosphere. Particle fallout from Saharan dust clouds is known to fertilize tropical forests—including the Amazon (bottom center of image). Because they are composed of wind blown particles and not water vapor, Saharan dust clouds carry aloft not only minerals and nutrients, but microscopic and macroscopic life too.

Is this particular Saharan dust cloud going to impact the Amazon? What might the meteorological and biological effects of this cloud be if it continues into the Caribbean and even into the United States? Might we be showered by little pieces of the Sahara this summer? Will we see spectacular sunrises and sunsets? Time will tell.

Here it is—just as it happened, recently in the lower Susquehanna valley.

SOURCES

Sedaghat, Safoura, Seyed Abbas Hoseini, Mohammad Larijani, and Khadijeh Shamekhi Ranjbar. 2013. “Age and Growth of Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758) in Southern Caspian Sea, Iran”. World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences. 5:1. pp.71-73.

Today’s arrivals—Neotropical migrants found in a streamside thicket in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed this morning…

After nearly a full week of record-breaking cold, including two nights with a widespread freeze, warm weather has returned. Today, for the first time this year, the temperature was above eighty degrees Fahrenheit throughout the lower Susquehanna region. Not only can the growing season now resume, but the northward movement of Neotropical birds can again take flight—much to our delight.

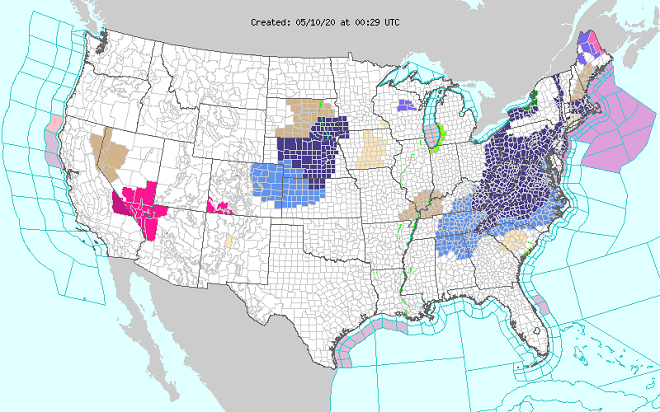

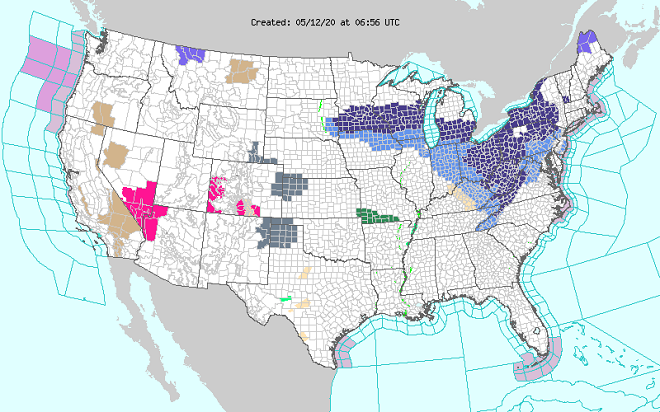

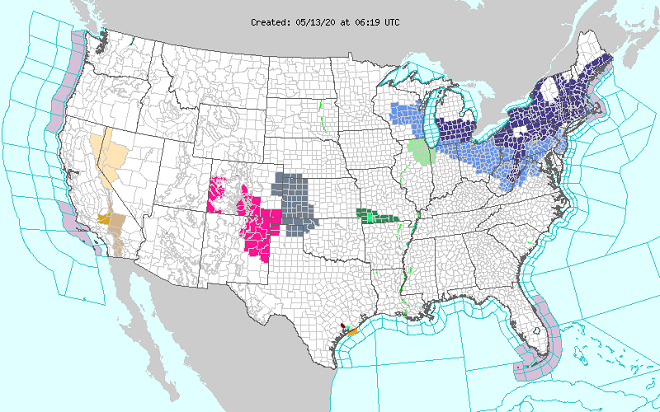

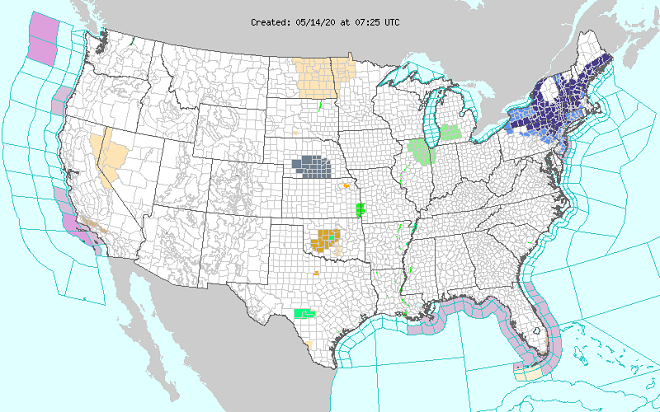

A rainy day on Friday, May 8, preceded the arrival of a cold arctic air mass in the eastern United States. It initiated a sustained layover for many migrating birds.

Freeze warnings were issued for five of the next six mornings. The nocturnal flights of migrating birds, most of them consisting of Neotropical species by now, appeared to be impacted. Even on clear moonlit nights, these birds wisely remained grounded. Unlike the more hardy species that moved north during the preceding weeks, Neotropical birds rely heavily on insects as a food source. For them, burning excessive energy by flying through cold air into areas that may be void of food upon arrival could be a death sentence. So they wait.

Today throughout the lower Susquehanna region, bird songs again fill the air and it seems to be mid-May as we remember it. The flights have resumed.

Some of the newest mothers in the lower Susquehanna valley—nurturing their young.

And a soon-to-be mother making the necessary preparations to bring a new generation into the world.

Have a Happy Mother’s Day!

You need to get outside and go for a walk. You’ll be sorry if you don’t. It’s prime time to see wildlife in all its glory. The songs and colors of spring are upon us!

If you’re not up to a walk and you just want to go for a slow drive, why not take a trip to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area and visit the managed grasslands on the north side of the refuge. To those of us over fifty, it’s a reminder of how Susquehanna valley farmlands were before the advent of high-intensity agriculture. Take a look at the birds found there right now.

And remember, if you happen to own land and aren’t growing crops on it, put it to good use. Mow less, live more. Mow less, more lives.

And now, a few words from the old watersnake who happens to live down along the creek where last spring’s Earth Day events were held.

Hey! You! Yeah You! I heard that there won’t be an Earth Day celebration down here this week. What a ssshame!

Remember how much fun we had last year. All those kids ssscrambling down along the creek bank throwing ssstones and ssscreaming and yelling like they’re gonna sssack a city. I ssshould have had the sssense to ssslither away. But no, I just curled up and played it cool. But sssure enough, one of the little brats found me and bellowed out loud enough for the whole countryside to hear, “SSSNAAAAKE!”

Ah nuts. That’s all it took. Here they come. Poking me with a ssstick. Taunting and ssstabbing. Don’t you know that hurts? What did I ever do to you, you rotten little apes? I’m telling ya, I get no respect.

Think that’s bad? It got worse. Don’t you remember? After a dozen of the runny-nosed monsters had me sssurrounded, one of the brain-dead adults yelled, “…it might be poisonous!”

That’s all it took. The ssstones got hurled my way and the poking with a ssstick became beatings. Those rats tried to kill me! On Earth Day! I ssslid into deep water and barely escaped with my life.

Now I want to tell you a few things—let’s get ’em ssstraight right now. I’m not, nor is any other watersnake in the SSSusquehanna valley, poisonous. Ssso don’t go villainizing me and those like me just because you have a monkey-like fear of us and need a sssocially acceptable reason to exercise your murderous instincts. Yeah, we know all about your manly tall tales of conquest that you ssshamelessly tell your friends and family after you kill a sssnake. Wanna be a hero? Then leave us alone! We and all of the native sssnakes of the SSSusquehanna valley, including the venomous copperheads and Timber Rattlesnakes, are minding our own business and just want to be left alone. Get it? Leave us alone! Don’t beat us with a ssshovel, mow over us, drive your car or truck over us, or ssshoot us. We have it bad enough as it is. You already buggered up most of our homes building your roads, houses, and lawns you know—so have a little respect. And one more thing, we don’t want be part of your pet menagerie. There’s no way we’ll “love you” or want anything to do with you, even if you do imprison us and make us sssubmissive to you for food, you sssick fascists. And that goes for you obsessive collector types too. We know you’re hoarding animals like us and calling your cruel little pet penitentiary a “rescue”. Yeah, we’re wise to that con too.

Ssso we’ve heard you won’t be coming down to the creek to terrorize us this year. No Earth Day event, huh. Well good, because I can’t take another Earth Day. Let the sssquirrels and the birds plant the trees, they do a better job than you anyway. Ssstay at home where you belong—watching television or twit-facing your B.F.F. on that magic box you carry around. And if you absolutely feel the urge to be upset by a sssnake in your midst, go visit that neighbor with the “reptile rescue”, I’m sssure he has a cobra or some other non-native sssnake in his collection that really ought to give you worry—especially when it finally escapes that prison.

It’s interesting to watch germophobes—and now coronaphobes—in action.

Some germophobes are very sanitary. They’ve practiced aseptic measures for most of their lives and have learned how clean and disinfect themselves and their surroundings quite well. Good for them.

Then there are those germophobes who are really bad at it. They’ve had years and years of practice, but they still can’t get it right. The public restroom is their absolute worst terror. They’ll empty the soap and sanitizer bottles into the mounds of paper towels they’ve stripped from the dispensers on the wall. Then they’ll wipe and scrub the privacy walls, flushable fixture, counter top, and sink they intend to use. (They don’t seem to bother with cleaning the mirrors though; I guess they’re too busy.) The puddles of dripped water leave a trail from the sink to their chosen stall of comfort. Then more paper towels are hauled off to try to dry the sloppy mess they’ve made. Then comes the clincher—not daring to get near a dirty trash can, they flush the giant wad of paper down the toilet and clog it. In frustration, they flush again and again until finally, they flood the entire restroom with sewer water. Then they panic and scurry away without ever finishing the business they started, if you know what I mean. How does your editor know these things? Well, for several years your friendly editor was a repairman in a series of very busy travel terminals, and it was he who got the call to undo the damage. It was an absolute nightmare, and it happened almost every day.

Now that we’re under don’t-call-it-martial-law-martial-law and compliant types are wearing masks while they work or cure their uncontrollable cravings to shop, it’s getting difficult to separate the germophobes from all these coronaphobes and other mask newbies.

I suspect that the handful of people I see in public using a mask as it was designed and then disposing of it properly upon removal have had some sort of medical or laboratory experience sometime in their lives—or they’re one of the skilled master germophobes. Good for them.

The real challenge comes when trying to separate the bumbling germophobe from the new recruits—the sloppy coronaphobes and the not-so-inspired mask-wearers who have been coerced into donning a rag so that they can work or get food. They all share a set of common practices that make telling them apart impossible. First, they’re fussing with the mask. They’ve got their hands on it. They’re pulling it up. Then they’re pulling it down, moving it to their left, then to their right. Crud on their hands gets on the mask, and the creepy crawlies from the mask get on their hands. Mask to hands to everything they touch. It’s almost the equivalent of having their hands in their mouth before pulling them out to grab the door handle, merchandise, or money. Then there’s this common sight—they pull the mask down around their neck for a while, just to smear the stuff that’s inside the mask onto the outside surface, and vice versa. It’s a microbiologists dream (or nightmare) by now. Then they’ll walk around with the mask down over their mouth without it covering their nose, maybe for a half hour or so. Breathing all over the outside before reaching up and pulling it over their nose again. On and on this goes, sometimes for hours or maybe even the whole day. Best of all though is the removal of the mask. It doesn’t go into the trash. Nope, might need it again sooner or later. It’s on the desk, the papers, and the keyboard. Then, it’s hanging over the chair for a while to dry off a little bit. It’s on the dashboard, the car seat, or hanging around the rear view mirror. Look, the dog’s playing with it. Isn’t that cute. Yeah, swell. It might even end up in the grocery bag, but never ever in the trash. And for the life of me, I can’t tell if I’m watching a really fouled-up germophobe or a new amateur in action.

Let’s face it—the use of masks by the general public is a placebo. They aren’t being used correctly and because of it, they offer minimal, if any, protection. Despite rhetoric to the contrary, people wearing masks voluntarily wear them in an attempt to protect themselves, number one, numero uno. These are the coronaphobes. They want to coerce others into wearing masks so that they themselves might be protected. The Republicrats, Democans, bureaucrats, and corporations running “Operation Boxer Shorts” (Objective: cover your @&&) have ignored the advice of researchers on the matter to go along with this silliness—to protect and/or further their own enterprise no doubt. The Centers for Disease Control say they reversed their own advice on masks-for-all not because there’s sound evidence that their effect outweighs their misuse, but because asymptomatic cases of Wuhan flu were discovered. As Foster Brooks used to say, “cockypop!” But okay, fine, so we’ll wear a mask, even though it’s more of a placebo than a prophylactic. We’ll do it just to make you happy. But could you at least pick up after yourself and wash your hands? Oh, and put the masks and gloves in the trash, don’t flush em’ down the commode. Thanks!

I keep wondering how all of this is gonna shake out in Sweden. You know, Sweden, where they didn’t have a lock-down to eviscerate small business and labor while fighting the flu. Yeah, Sweden, where they’re trying a defensive-offensive strategy—protect the most vulnerable (the defense) while allowing natural resistance to develop among enough members of the population to cripple transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (the offense). I’ve been very interested in that strategy. I’ll be watching.

Just in case anybody feels the need, here, again, are the sources on mask wearing.

SOURCES THAT APPARENTLY NOBODY READS

Broseau, Lisa M., and Margaret Seitsema. 2020. “Commentary: Masks-for-all for COVID-19 Not Based on Sound Data”. University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Policy https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/04/commentary-masks-all-covid-19-not-based-sound-data Accessed April 10, 2020.

Davies, Anna, Katy-Anne Thompson, Karthika Giri, George Kafatos, Jimmy Walker, and Alan Bennett. 2013. “Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic?”. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 7:4. pp. 413-418.

MacIntyre, C. Raina, Holly Seale, Tham Chi Dung, Nguyen Tran Hien, Phan Thi Nga, Abrar Ahmad Chughtai, Bayzidur Rahman, Dominic E. Dwyer, and Quanyi Wang. 2015. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Cloth Masks Compared with Medical Masks in Healthcare Workers. BMJ Open. 5:e006577. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577.

Fifty years ago, the world’s attention was fixed on the fate of the Apollo 13 astronauts—Commander Jim Lovell, Lunar Module Pilot Fred Haise, and Command Module Pilot Jack Swigert—after an explosion disabled their spacecraft and changed a mission to explore the moon into an improvised operation to return them safely to the earth. Perhaps this anniversary comes at a fortuitous time. The story of Apollo 13 may have parallels and lessons pertinent to present-day events and the concerns of people in America and around the world.

In April, 1970, Jack Swigert was a last-minute replacement for the original Apollo 13 Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly after Mattingly was exposed to German measles (rubella) prior to the mission. Mattingly had been training with fellow backup crew members John Young and Charles Duke when Duke came down with the disease after he and his family had visited friends whose three-year-old son was suffering the effects of the infection. NASA was wary of contagions that could spread among the astronauts while isolated in a space capsule during a lengthy journey, possibly incapacitating the entire crew. Tests on the astronauts found that Mattingly, like Duke, had lacked antibodies to the rubella virus and could therefore become ill during the flight. Mattingly alone could get sick—Lovell and Haise, possessing resistance to rubella, could not. Nevertheless, the decision was made to substitute Swigert for Mattingly. Swigert proved competent for the late change partly because he had developed many of the emergency procedures for operating the Command Module. Mattingly, who never did get measles, along with Duke and Young, would be the crew for the Apollo 16 moon landing in April, 1972.

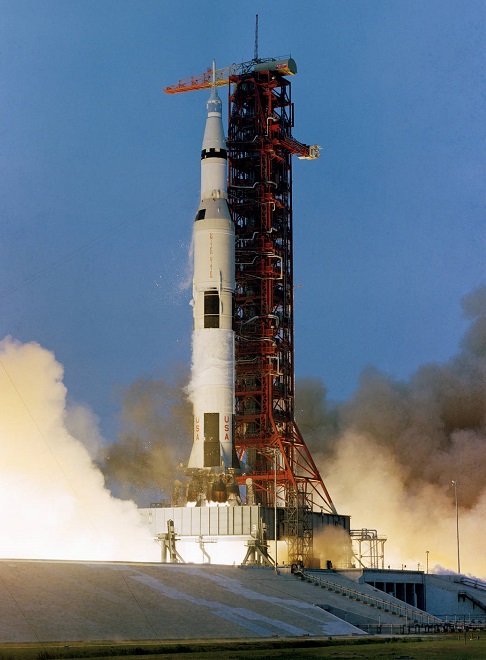

Apollo 13 was launched as scheduled on April 11, 1970, at 2:13 P.M. E.S.T. and was on its way to a planned third landing on the lunar surface.

After two successful landings, network television found no sensation in the story of yet another trip to the moon. There was little coverage of the mission’s first fifty-five hours. Then, fifty-five hours and just more than fifty-five minutes into the flight, and just two minutes after fulfilling Mission Control’s request to turn on fans to stir the oxygen tanks so that their contents could be measured, Jack Swigert radioed, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” Then Lovell repeated his message, “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” Within a minute, Fred Haise was listing some metering anomalies and alarm activations for Mission Control and added, “And we had a pretty large bang associated with the caution and warning there.” Apollo 13 was about 205,000 miles from earth—it was just after 10 P.M. E.S.T., April 13, 1970.

Thirteen minutes after the “bang”, Lovell radioed Mission Control while looking out the capsule’s window, “We are venting something out into the…into space.” Apollo 13 was losing it’s oxygen, and its electric supplies. They didn’t know it at the time, but oxygen tank number two had exploded and damaged either a valve or tubing on tank number one—the Command Module’s only other source of oxygen—and both were losing their contents into space. Two of the three fuel cells had failed as well. Without oxygen, the remaining fuel cell in the Service Module would fail to make electricity for operation of the Command Module. Worse yet, the astronauts would not be able to breathe. Without delay, engineers and scientists on the ground went into action to develop alternatives to the original flight plan.

Power in the Command Module had to be conserved for reentry, so with just fifteen minutes of electricity remaining, Lovell and Haise moved into the “lifeboat”, the Lunar Module, and began powering it up while Swigert finished shutting down the systems aboard Odyssey to conserve its remaining energy for the end of the mission. Haise, who had spent fourteen months at Grumman’s manufacturing facility on Long Island, was intimately familiar with the Lunar Module’s operating systems. He powered-up essential systems and began calculating whether the consumables on Aquarius would last for the time it would take to go around the moon and “slingshot” back to earth.

To change the course of Apollo 13 from a moon orbit trajectory to one that would whip around the back of the moon and send them home, Lovell used the Lunar Module’s descent engine to perform a 35-second-long course correction burn. This burn commenced five hours after the explosion at 3:43 A.M. E.S.T. on the morning of April 14. Apollo 13 was then on a free-return trajectory to loop around the moon and return to earth.

Haise had in his possession notes from previous missions which he consulted to determine that they would run out of water about five hours before returning to earth. Fortunately, his notes also showed that the spacecraft’s mechanical systems could remain viable without water cooling for seven or eight hours. Astronauts reduced their water intake to six ounces a day, one fifth of normal, and attempted to compensate by drinking fruit juices and eating wet-packed hot dogs and similar foods. Their efforts to conserve water succeeded, but did lead to the crew becoming dehydrated.

For breathing, there was a sufficient supply of oxygen in the Lunar Module ascent stage where the astronauts would be taking refuge for the remaining four days of the journey. As a backup, there was oxygen in the two suits that were intended for the moonwalk and two more tanks in the ascent stage of Aquarius. Less than half of the oxygen supply was used during the return trip.

Procedures worked out by engineers and tested in a simulator on the ground allowed the crew to use only one fifth of the power normally required during the Lunar Module’s intended forty-five hours of useful life, thus enabling its batteries to last for a ninety-hour-long return trip and add charge to the Command Module batteries—with some energy to spare. To make it back to earth within the ninety-hour time window, the return trip would need to be shortened by nine hours.

The trajectory of Apollo 13’s loop behind the moon had carried them further away from earth than any other humans have ever gone. Two hours after swinging around the moon, Lovell prepared to perform a second burn with the Lunar Module’s descent engine—five minutes in duration—to increase Apollo 13’s return speed and shorten the time it would take to get back home. For navigational alignment during the burn maneuver, debris around the spacecraft made using the sextant to sight stars impossible. Scientists on the ground came up with coordinates allowing Lovell to use the sun as a navigation reference instead. The burn was a success.

Lithium hydroxide canisters remove the carbon dioxide gas, which is continuously produced by the respiration of the astronauts, from the atmosphere of a spacecraft. The Lunar Module’s canisters were designed to protect two astronauts for two days. Because it was being used as a “lifeboat”, Aquarius was hosting three astronauts for four days. After one and a half days of use by three men, an alarm warned that the carbon dioxide levels in the Lunar Module were getting dangerously high. Spare canisters from Odyssey could be used, but there was a problem—they were square, those used on Aquarius were round.

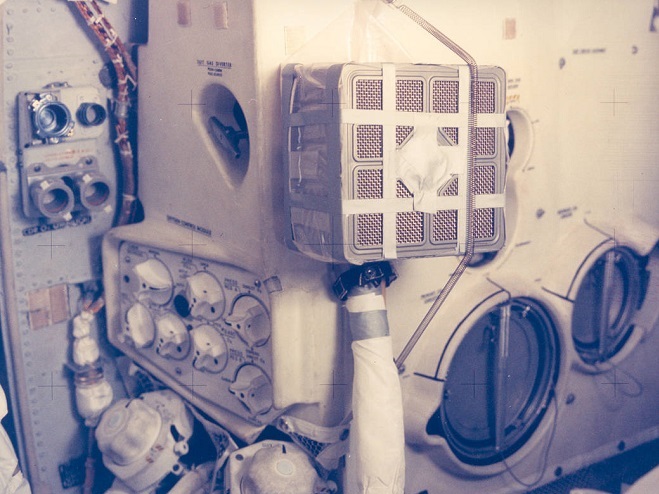

Engineers on the ground went to work using materials that would be available aboard the Apollo 13 spacecraft to improvise a solution. They came up with an adapter design using duct tape, a plastic bag, and cardboard to fabricate a “mailbox” that would attach square lithium hydroxide canisters to the round air handling tubes in the Lunar Module. After testing on the ground, the detailed verbal instructions for constructing the life-saving invention were radioed by Joe Kerwin from Mission Control to Aquarius. Haise and Swigert assembled and installed two of the life-saving devices. Carbon dioxide levels soon dropped back within acceptable parameters.

The astronauts endured a lack of sleep, heat, water, and food during the trip home. All were dehydrated and collectively they lost over thirty pounds of body weight. As they approached earth, the crew prepared to implement the new procedures for re-energizing the cold damp systems of the Command Module. Ground personnel had drafted and tested this set of startup instructions in just three days instead of the thirty days that such work usually requires. It was critical that the circuits that were energized did not collectively exceed the amperage available from the batteries on Odyssey.

Jack Swigert carefully brought Odyssey back to life using the new procedures, which were radioed, step by step, from Mission Control. Short circuits, feared due to the moisture that had condensed on all the cold surfaces in the Command Module, were not a problem. Improvements to the insulation on the wiring and electrical components throughout the interior of the space capsules following the Apollo 1 fire is believed to have safeguarded against any mishaps.

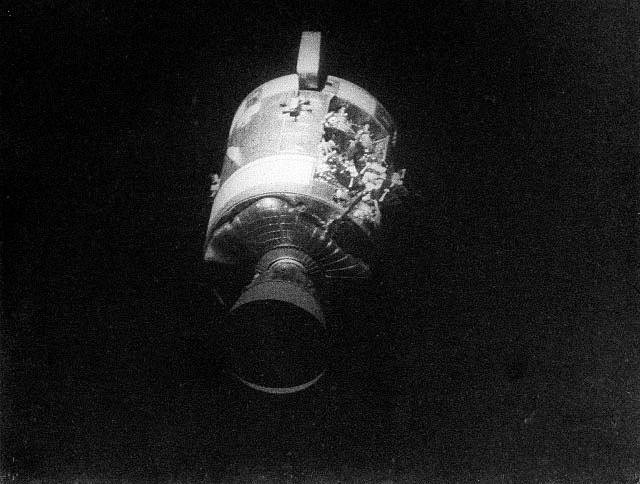

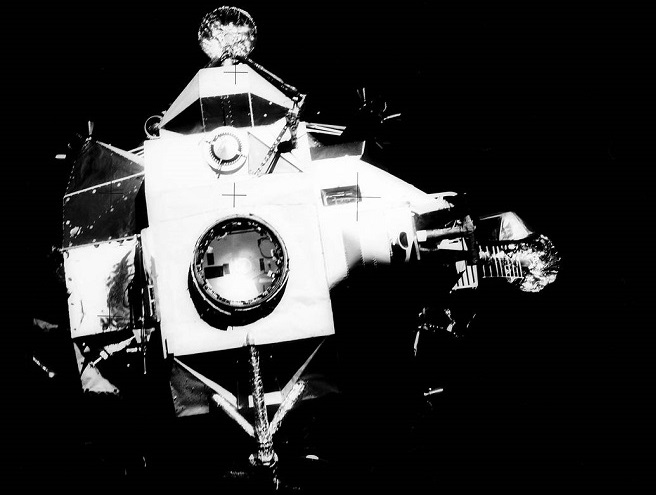

Four hours before reentry, at 8:15 A.M. E.S.T. on April 17, 1970, the Service Module was jettisoned and photographed as the crew got its first look at the damage caused by the explosion. Just an hour before reentry, Lovell and Haise joined Swigert in the Command Module. At 11:43, the Lunar Module was jettisoned and drifted away.

Apollo 13 reentered earth’s atmosphere and experienced the usual communications blackout as the capsule sizzled through an envelope of ionized air. Mission Control and the world rejoiced as cameras televised images of deployed parachutes and a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean less than four miles from the recovery ship, the U.S.S. Iwo Jima, at 1:08 P.M. E.S.T. Possibly as many as one billion people were watching.

The families of the astronauts had traveled aboard Air Force One along with President Richard Nixon to Honolulu, Hawaii, and were waiting for the Apollo 13 crew when they arrived there from American Samoa on April 18. Nixon presented the men with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“…The men of Apollo 13, by their poise and skill under the most intense kind of pressure, epitomize the character that accepts danger and surmounts it…Theirs is the spirit that built America.”

Among the greatest legacies of the earth orbit and moon missions were the scientific and technological achievements that allowed people to live and travel in space using a minimum of resources. Apollo 13 took these minimums to the extreme—using everything as effectively and efficiently as possible. It was one of the pinnacle achievements of the manned spaceflight program.

Fifty years later, are we embracing these and more recent innovations to live comfortably but wisely?

President John F. Kennedy, in his 1962 speech at Rice University, beckoned Americans to strive for a seemingly unreachable goal. A goal that would motivate a people to determine their own destiny and not have destiny determined for them.

“…We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone…”

Kennedy urged his country to take the risk and go to the moon. Despite the dangers, despite the hesitations of the medical community, and in spite of the naysayers, they accepted the challenge and succeeded.

Have Americans lost the will to shape their own destiny? Are they content with blind obedience, mediocrity, and shopping with a dirty rag over their face? Let your friendly editor give you a hint. The people who happen to be front and center in the news today, fifty years after Apollo 13, aren’t rocket scientists. In fact, they have a hard time swallowing anything science has to offer, unless, of course, it can be twisted to back up their sneaky little schemes. But they’re the leadership—elected dimwits and entrenched bureaucrats—and they rule by consent of the governed. So the matter is decided. Look at the bright side though, at least the creeps have a career to protect, so we’ll always be certain of their motivation.

SOURCES

Lovell, James A. 1975. “Houston, We’ve Had A Problem; A Crippled Bird Limps Safely Home”. Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, DC. pp. 247-263.

SOURCES THAT APPARENTLY NOBODY READS

Broseau, Lisa M., and Margaret Seitsema. 2020. “Commentary: Masks-for-all for COVID-19 Not Based on Sound Data”. University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Policy https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/04/commentary-masks-all-covid-19-not-based-sound-data Accessed April 10, 2020.

Davies, Anna, Katy-Anne Thompson, Karthika Giri, George Kafatos, Jimmy Walker, and Alan Bennett. 2013. “Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic?”. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 7:4. pp. 413-418.

MacIntyre, C. Raina, Holly Seale, Tham Chi Dung, Nguyen Tran Hien, Phan Thi Nga, Abrar Ahmad Chughtai, Bayzidur Rahman, Dominic E. Dwyer, and Quanyi Wang. 2015. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Cloth Masks Compared with Medical Masks in Healthcare Workers. BMJ Open. 5:e006577. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577.

For those of you who dare to shed that filthy contaminated rag you’ve been told to breathe through so that you might instead get out and enjoy some clean air in a cherished place of solitude, here’s what’s around—go have a look.

The springtime show on the water continues…

Hey, what are those showy flowers?

Wasn’t that refreshing? Now go take a walk.

As a public service to our susquehannawildlife.net visitors, Uncle Tyler Dyer has agreed to give us a summary of the news. Uncle Ty is currently in self-imposed quarantine and will continue to remain in isolation until the threat from SARS-CoV-2 passes. Despite his age, he’s not particularly concerned about exposure to the virus or the Wuhan flu; he’s worried about getting bit by one of the “friendly” dogs that are presently dragging their owners down the sidewalks and recreation trails throughout the Susquehanna valley on a daily basis. Worse yet, he dreads the thought of winding up in the E.R. because he got bit by one of their kids. So until the subdivision dwellers go back to work and school, Uncle Ty will remain, like always, out of sight.

To get the latest scoop, be assured that Uncle Ty will poll his many exclusive sources, most of them unavailable to mainstream news reporters. He not only knows people in high places, he knows high people in places.

Here’s the news.

Hey man, I’m Ty Dyer and here’s what’s happening.

The Flat Earth Coalition of Environmental Scientists is advising the public to be alert for an impending threat posed to those who exercise “social distancing”. According to a forthcoming report, if everyone were to maintain a distance of six feet between themselves and all other individuals, those persons around the physical periphery of the mass of humanity will be dangerously close to the horizon’s end. Despite the effects of COVID-19, the world population is still growing by more than 200,000 persons each day. Soon, the earth will become overcrowded and people will begin falling off the planet, possibly within the next several weeks. A spokesperson warned that pushing, shoving, and name-calling could precede the eventual dumping of the weakest from the crowd over the side to make more space. F.E.C.E.S. would not speculate on the fate of those who take the dump; however, those living near the rim are advised to wear a face mask and a parachute while doing their business. Critics were quoted as saying, “The F.E.C.E.S. movement is full of it.”

Meanwhile, the Face Mask Manufacturers Alliance is asking those who are not sick, are not healthcare workers, or have not been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 to stop misusing their products, particularly while there is a severe supply shortage. They warn users that their masks are designed to prevent those who have been exposed to the flu virus or another contagion from transmitting it to others by capturing the aerosols produced by breathing, speaking, coughing, or sneezing. For those who have no flu symptoms or other evidence of exposure, but who insist upon wearing a mask to prevent contracting the virus despite that use being an application inverse to its design, the manufacturers ask that you please turn the mask inside out before donning. To alert others of your status, you are requested to wear your outer garments inside out as well. If you are exposed to SARS-CoV-2, test positive for the virus, or have symptoms of the flu or other contagious illness, you are instructed to wear a mask as designed, right-side out, to prevent contaminating those around you. You can also then turn your clothing right-side out as well.

There is controversy in several northeastern cities today after police officers arrested dozens of people for failing to practice safe “social distancing”. Each of those cited was quickly released to avoid crowding of the precinct houses. The controversy arose when representatives of the cities’ vice squads insisted that enforcing “social distancing” laws comes under their jurisdiction. They reminded city officials that after all, it was the vice squads who for decades have made it clear that violations of “social distancing” laws are not victimless crimes. They then accused city governments of underfunding their operations in an attempt to force them to surrender “social distancing” enforcement to patrol officers while the limited resources of the vice squads deal with the lingering jumbo soda epidemic.

Astronomers today released a statement saying that in deference to the importance of safe “social distancing”, they would eliminate using Gemini as the name of a well-known constellation until further notice. The stars comprising the Gemini twins will now be divided among two new constellations called Hank and Marty. Scientists pointed out that the stars comprising Hank and Marty are actually many light-years apart; it is our vantage point on earth that makes the two men appear to be violating the practice of safe “social distancing”. Nevertheless, they didn’t want Gemini setting a bad example.

Radio broadcasters have announced that many classic rock and pop recordings have been edited and remastered to reflect increased awareness of safe “social distancing”. Here are a few of the slightly amended hits you’ll be hearing on the airwaves soon.

The Beatles—I Want To Hold Your Hand (But My Arms Ain’t Long Enough)

The Beatles with Billy Preston—Get Back (To The Tape Mark On The Floor)

The Beatles—(This Really Isn’t A Good Time To) Come Together

The Captain & Tennille—Love Will Keep Us Together (But You Better Stand Over There)

The Carpenters —(Not So) Close To You

The Jackson 5—I’ll Be There (Or Better Yet Over Here)

Michael Jackson—Beat It (extended remix)

Bette Midler—From A Distance (Remastered)

Olivia Newton-John—(This Is No Time To Get) Physical

Pink Floyd—Comfortably Numb (You Best Skedaddle)

The Police—Don’t Stand So Close To Me (32 minute extended remix)

The Police—Every Breath You Take (You’re Suckin’ In What I Just Exhaled)

Elvis Presley—Love Me Tender (From Over There)

The Rolling Stones—Get Off Of My Cloud (And Outta My Space)

Diana Ross & The Supremes—Someday We’ll Be Together (But Not Right Now)

The Temptations—I Can’t Get Next To You (Remix)

And that’s what’s going on for April 1, 2020. Ty Dyer saying stay home, don’t get strung up in the puppet show, and remember, there are two different Amazons out there, and the only good one is a river.

Fog and mist lingered throughout the day, as did the migratory water birds on the river and lakes in the lower Susquehanna valley. As a continuation of yesterday’s post on the fallout, here’s a photo tour of some of the sites where ducks, loons, grebes, and other birds have gathered.

Stormy weather certainly is a birder’s delight.

Local birders enjoy going to the Atlantic coast of New Jersey and Delmarva in the winter. The towns and beaches host far fewer people than birds, and many of the species seen are unlikely to be found anywhere else in the region. Unusual rarities add to the excitement.

The regular seaside attraction in winter is the variety of diving ducks and similar water birds that feed in the ocean surf and in the saltwater bays. Most of these birds breed in Canada and many stealthily cross over the landmass of the northeastern United States during their migrations. If an inland birder wants to see these coastal specialties, a trip to the shore in winter or a much longer journey to Canada in the summer is normally necessary—unless there is a fallout.

Migrating birds can show up in strange places when a storm interrupts their flight. Forest songbirds like thrushes and warblers frequently take temporary refuge in a wooded backyard or even in a city park when forced down by inclement weather. Loons have been found in shopping center parking lots after mistaking the wet asphalt for a lake. Fortunately though, loons, ducks, and other water birds usually find suitable ponds, lakes, and rivers as places of refuge when forced down. For inland birders, a fallout like this can provide an opportunity to observe these coastal species close to home.

Not so coincidentally, it has rained throughout much of today in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, apparently interrupting a large movement of migrating birds. There is, at the time of this writing, a significant fallout of coastal water birds here. Hundreds of diving ducks and other benthic feeders are on the Susquehanna River and on some of the clearer lakes and ponds in the region. They can be expected to remain until the storm passes and visibility improves—then they’ll promptly commence their exodus.

The following photographs were taken during today’s late afternoon thundershower at Memorial Lake State Park at Fort Indiantown Gap, Lebanon County.

Migrating land birds have also been forced down by the persistent rains.

Why not get out and take a slow quiet walk on a rainy day. It may be the best time of all for viewing certain birds and other wildlife.

To avoid any theft of the limelight from the country’s miscreants who are currently using the year’s most worrisome virus strain , SARS-CoV-2, as a cover for wealth realignment and self-promotion, this week’s 41st anniversary observance of the 1979 nuclear accident at Three Mile Island has been cancelled. The planned community reenactment festivities will not be held this year.

We will not be recreating the run on the stores or the hoarding of toilet paper, ammunition, food, booze, smokes, prophylactics, and pet treats. Though not sanctioned by the official event, undocumented pharmaceutical distributors will still be vending product to the self-medicated at the usual locations, reminiscent of 1979 commerce.

The Friday night disco get-together featuring authentic vintage 8-track tape music is called off, which of course means that commemorative T.M.I.-2 anniversary t-shirts will not be available for sale this year. If you were thinking of attending, be assured that you can find audio of the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” on the internet and play it three times just like it would have been repeated at the dance. You can find other event favorites online too, including the Trammps’ “Disco Inferno”.

The annual “evacuation excursion” to the mountains of Pennsylvania led by the gasoline and gunpowder gang to terrorize the countryside with four-wheel drive trucks, all-terrain vehicles, fireworks, and random weapon discharges is scrubbed. The traditional trash burning in the fire pit on Saturday afternoon and weenie roast scheduled for Saturday night are nixed. Regular participants will have to inhale and ingest their dose of dioxins somewhere else this year.

The consortium of local college drama clubs will not be presenting their popular horror play “It’s Gonna Blow Up”, featuring authentic rumors and supposition from actual news media reports about the 1979 accident. Mock briefings featuring posturing politicians trying to patronize their donors without endangering their reelection prospects will not be held and have been eliminated from the slate of activities—they seem too familiar to be of any interest. A slapstick comedy interpretation of bureaucrats trying to assume authoritarian power to implement an emergency plan that never existed has been postponed until a future event.

Speakers due to share their insights at this year’s gathering have been asked to return next time. We’re pleased that each has agreed. It’s a splendid roster of advocates both for and against nuclear energy, each of whom has shamelessly abandoned their integrity to sustain a do-nothing career that protects them from ever breaking into a sweat. As usual, these appearances will be scheduled as the final feature of the weekend to assure a prompt dispersal of the crowd.

We hope to see you all sometime soon. In the meantime, please remember to use the euphemism “essential workers” when referring to the expendable labor that is out there protecting public health and assuring that everyone can keep shopping. We as a nation would hate for them to realize their worth—they may expect to be better compensated.

As spring begins, our thoughts often turn, if only briefly, to the sun and the welcome effect its higher angle in the sky and the lengthening hours of daylight will have on our winter-weary lives. Soon, spring thunderstorms and warm humid air will make our crops thrive. Plant buds will open to reveal flowers and leaves, and wildlife will hurry to raise a new generation. We’re reminded that the sun is the source of earth’s life—and is its ongoing benefactor.

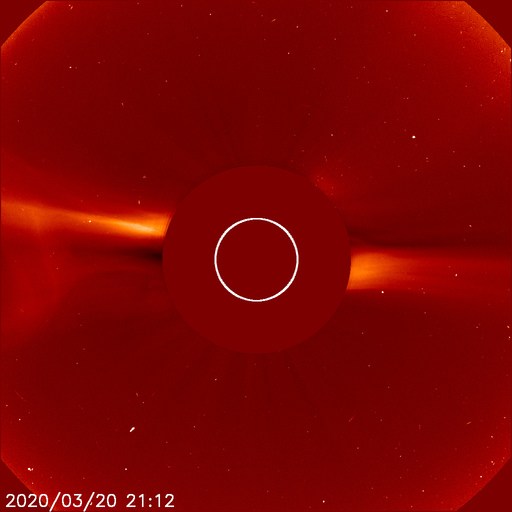

Coincidentally, there was, during the first full day of spring, an explosion of plasma from the sun—a Coronal Mass Ejection. It happened to occur on the side of the sun currently facing away from earth, so the enormous cloud of magnetic energy won’t be affecting radio communications or electric transmission here.

Friday’s Coronal Mass Ejection can be seen in the following series of images. To protect the camera’s sensor, the direct light of the sun was blocked by an occulter at the center of each picture. The location of the sun’s disk is indicated by the white circle. In this set, the ejected plasma appears as a cloud emerging from behind the left side of the shield and racing millions of miles into space. The speed of a plasma cloud produced by a Coronal Mass Ejection varies. When directed at earth, some can reach our planet in less than a day—others may take several days to arrive.

Currently though, the term “Coronal Mass Ejection” may cause one to bristle and think of concerns other than the cosmos—Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the Wuhan flu chief among them.

Well, perhaps the promise of warming weather and humid days will help assuage our anxieties.

Colds and flu are certainly more prevalent in winter than during the other seasons of the year. Cases of these diseases begin creeping through schools and workplaces just in time for the year-end holidays. They persist into early spring each year. Then, as we spend more time outdoors in the sunshine and fresh air of April and May, their incidence wanes. Soon the sneezing and coughing is mostly pollen-related and less often the result of transmitted viruses.

In addition to our liberation from buildings crowded with people, spring heat introduces another factor that is apparently responsible for subduing the rapid transmission of viruses—humidity. February and March are typically the driest months of the year in the lower Susquehanna valley. The air outside is cold and dry. The air inside a heated building can be worse.

Researchers have found that viruses in aerosols produced by coughing, sneezing, breathing, and talking survive longer in drier air than in humid air. A NIOSH and CDC funded study (Noti, et al., 2013) mechanically “coughed” aerosols containing H1N1 virus into a simulated examination room. They discovered that “…one hour after coughing, ∼5 times more virus remains infectious at 7-23% RH (relative humidity) than at ≥43% RH.” This is a significant discovery and may shed light on why the end of heating season and the arrival of warmer humid springtime air coincides with the end of cold and flu season. The study’s analysis determined that “Total virus collected for 60 minutes retained 70.6-77.3% infectivity at relative humidity ≤23%, but only 14.6-22.2% at relative humidity ≥43%.” Specifically, they found that the greatest effect of higher relative humidity occurs during the first fifteen minutes after the cough, and that virus in droplets exceeding 4μM in diameter had the most significant reduction in that time—ninety percent.

It looks like a little global warming wouldn’t hurt right now.

So remember, respect the sun—fear asteroids.

SOURCES

Burnham, Robert, Alan Dyer, Robert A. Garfinkle, Martin George, Jeff Kanipe, and David H. Levy. 2006. The Nature Companions Practical Skywatching. Fog City Press. San Francisco, CA.

Noti, J.D., F. M. Blachere, C. M. McMillen, W. G. Lindsley, M. L. Kashon, D. R. Slaughter, et al. 2013. “High Humidity Leads to Loss of Infectious Influenza Virus from Simulated Coughs”. PLoS ONE. 8:2 e57485. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057485

The mild winter has apparently minimized weather-related mortality for the local Green Frog population. With temperatures in the seventies throughout the lower Susquehanna valley for this first full day of spring, many recently emerged adults could be seen and, on occasion, heard. Yellow-throated males tested their mating calls—reminding the listener of the sound made by the plucking of a loose banjo string.

If you venture out, keep alert for the migrating birds of late winter and early spring.

If you’re staying close to home, be sure to check out the changing appearance of the birds you see nearby. Some species are losing their drab winter basic plumage and attaining a more colorful summer breeding alternate plumage.

So just how many Green Frogs were there in that first photograph? Here’s the answer.

Happy Spring. For the benefit of everyone’s health, let’s hope that it’s a hot and humid one!

According to the most recent Pennsylvania Game Commission estimate, there are presently more than 100,000 Snow Geese at the Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area (W.M.A.) in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties. It’s a spectacular sight.

If you go to see these and other birds at Middle Creek, it’s important to remember that you are visiting them in a “wildlife refuge” set aside for, believe it or not, wildlife. “Wildlife refuge”, many would be surprised to learn, is short for “terrestrial or aquatic habitat where wildlife can find refuge and protection from all the meddlesome and murderous things people do”.

Nothing says Happy Valentine’s Day like a really bad poem, so here it is…

FOR THE LOVE OF DUCKS

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

My neighbors are complainin’

I can hear them talk

The mallards eat their garden

Let surprises on their walk

Dung stains on the carpets

They tracked it in the house

It’s from those ducks and not the pets

Can’t blame it on the spouse

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

Tamed with bread and crackers

I gave them as a treat

I soon found maimed dead quackers

Lying in the street

A driver who intended

To miss the hens and drakes

Had their car rear-ended

When they hit the brakes

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

The flock is very wasteful

Each bird a pound a day

Web-foots in a cesspool

Pollute the waterway

There are some kids playing

In that filthy ditch

Soon they’ll be displaying

The rash of Swimmer’s Itch

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

These ducks they do not migrate

They’re here day in, day out

Aquatic life they decimate

No plants, no fish, no trout

Hurry! Hurry! Heed my call

Before it starts to rain

Ten more ducklings took a fall

And are stranded in a drain

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

Have you people lost your minds?

I see you by your fence

These ducks are cute and I am kind

It’s you who’ve lost your sense

Beggars from the handouts

My God what have I done?

Their senseless habits leave no doubt

Their instincts are all gone

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

Now I know just what to do

Like one would teach a child

I’ll feed the ducks at the zoo

And let the rest live wild

So if you feed the duckies

Beware of the spell

Or you will do the same as me

Loving ducks to death as well

—Ducks Anonymous, LLC

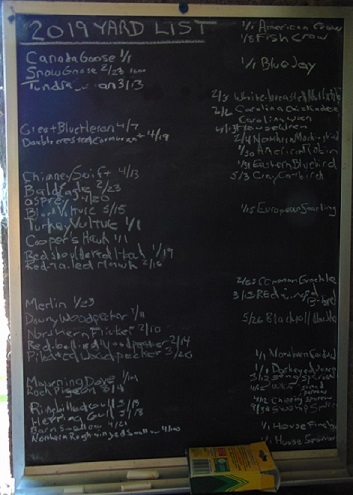

Inside the doorway that leads to your editor’s 3,500 square foot garden hangs a small chalkboard upon which he records the common names of the species of birds that are seen there—or from there—during the year. If he remembers to, he records the date when the species was first seen during that particular year. On New Year’s Day, the results from the freshly ended year are transcribed onto a sheet of notebook paper. On the reverse, the names of butterflies, mammals, and other animals that visited the garden are copied from a second chalkboard that hangs nearby. The piece of paper is then inserted into a folder to join those from previous New Year’s Days. The folder then gets placed back into the editor’s desk drawer beneath a circular saw blade and an old scratched up set of sunglasses—so that he knows exactly where to find it if he wishes to.

A quick glance at this year’s list calls to mind a few recollections.

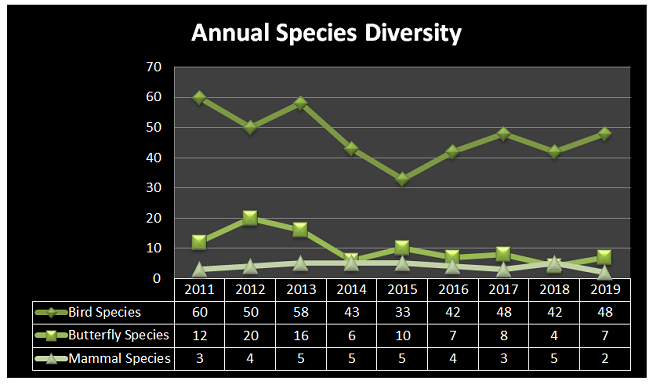

Before putting the folder back into the drawer for another year, the editor decided to count up the species totals on each of the sheets and load them into the chart maker in the computer.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

It appears that, at the very least, the garden habitat has been disconnected from the home ranges of many species by fragmentation. His little oasis is now isolated in a landscape that becomes increasingly hostile to native wildlife with each passing year. The paving of more parking areas, the elimination of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous growth from the large number of rental properties in the area, the alteration of the biology of the nearby stream by hand-fed domestic ducks, light pollution, and the outdoor use of pesticides have all contributed to the separation of the editor’s tiny sanctuary from the travel lanes and core habitats of many of the species that formerly visited, fed, or bred there. In 2019, migrants, particularly “fly-overs”, were nearly the only sightings aside from several woodpeckers, invasive House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and hardy Mourning Doves. Even rascally European Starlings became sporadic in occurrence—imagine that! It was the most lackluster year in memory.

If habitat fragmentation were the sole cause for the downward trend in numbers and species, it would be disappointing, but comprehendible. There would be no cause for greater alarm. It would be a matter of cause and effect. But the problem is more widespread.

Although the editor spent a great deal of time in the garden this year, he was also out and about, traveling hundreds of miles per week through lands on both the east and the west shores of the lower Susquehanna. And on each journey, the number of birds seen could be counted on fingers and toes. A decade earlier, there were thousands of birds in these same locations, particularly during the late summer.

In the lower Susquehanna valley, something has drastically reduced the population of birds during breeding season, post-breeding dispersal, and the staging period preceding autumn migration. In much of the region, their late-spring through summer absence was, in 2019, conspicuous. What happened to the tens of thousands of swallows that used to gather on wires along rural roads in August and September before moving south? The groups of dozens of Eastern Kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus) that did their fly-catching from perches in willows alongside meadows and shorelines—where are they?

Several studies published during the autumn of 2019 have documented and/or predicted losses in bird populations in the eastern half of the United States and elsewhere. These studies looked at data samples collected during recent decades to either arrive at conclusions or project future trends. They cite climate change, the feline infestation, and habitat loss/degradation among the factors contributing to alterations in range, migration, and overall numbers.

There’s not much need for analysis to determine if bird numbers have plummeted in certain Lower Susquehanna Watershed habitats during the aforementioned seasons—the birds are gone. None of these studies documented or forecast such an abrupt decline. Is there a mysterious cause for the loss of the valley’s birds? Did they die off? Is there a disease or chemical killing them or inhibiting their reproduction? Is it global warming? Is it Three Mile Island? Is it plastic straws, wind turbines, or vehicle traffic?

The answer might not be so cryptic. It might be right before our eyes. And we’ll explore it during 2020.

In the meantime, Uncle Ty and I going to the Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg. You should go too. They have lots of food there.

With autumn coming to a close, let’s have a look at some of the fascinating insects (and a spider) that put on a show during some mild afternoons in the late months of 2019.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

Late this afternoon, despite a cold bone-chilling rain, news media and crowds of onlookers gathered along the Susquehanna shoreline upstream of Three Mile Island at the small town of Royalton to catch a glimpse of the removal of a downed aircraft from the river. Back on October 4, a single-engine Piper PA46 Malibu was on the final leg of an approach to runway 31 at Harrisburg International Airport when it lost power. The pilot and passenger were uninjured during the emergency “splashdown” in the shallow water just short of the runway.

At 12:07 P.M., E.D.T. today, forty-five years and eighteen days after being commissioned into commercial service on September 2, 1974, the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station’s Unit 1 reactor was shut down for the final time. There will be no refueling. There will be no more electricity furnished to the grid by the plant. It is henceforth a user, not a producer, of energy.

Here’s the final shutdown, in pictures…

It’s that time of year when one may expect to find migratory Neotropical songbirds feeding among the foliage of trees and shrubs in the forests, woodlots, and thickets of the lower Susquehanna valley.

During a late afternoon stroll through a headwaters forest east of Conewago Falls outside Mount Gretna, I was pleased to finally come upon a noisy gathering of about two dozen birds. It had, previous to that, been a quiet two hours of walking, only the rumble of an approaching thunderstorm punctuated the silence. Among this little flock were some chickadees, robins, Gray Catbirds, an Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus), and a Hairy Woodpecker (Dryobates villosus). Besides the catbirds, there were two other species of Neotropical migrants; both were warblers. No less than six Black-throated Blue Warblers (Setophaga caerulescens) were vying for positions in the trees from which they could investigate the stranger on the footpath below. And among the understory shrubs there were at least as many Ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla) satisfying a similar curiosity.

When they depart the Susquehanna valley, these two warbler species will be southbound for wintering ranges that include Florida, many of the Caribbean Islands, Central America, and, for the Ovenbirds, northern South America. Their flights occur at night. During the breeding season and while migrating, both feed primarily on insects and other arthropods . On the wintering grounds, they will consume some fruit. It is during their time in the tropics that the Black-throated Blue Warbler sometimes visits feeding stations that offer grape jelly, much to the delight of bird enthusiasts.

Black-throated Blue Warblers and Ovenbirds commonly winter on the Florida peninsula and in the Bahamas. With the major tropical cyclone Hurricane Dorian presently ripping through the region, these birds are better off taking their time getting there. There’s no need to hurry. The longer they and the other Neotropical migrants hang around, the more we get to enjoy them anyway. So get out there to see them before they go—and remember to look up.

It’s a hot summer weekend with a sun so bright that creosote is dripping from utility poles onto the sidewalks. Dodging these sticky little puddles of tar can cause one to reminisce about sultry days-gone-by.

Sometime in July or August each year, about half a century ago, we would cram all the gear for seven days of living into the car and head for the beaches of Delmarva or New Jersey. It was family vacation time, that one week a year when the working class fantasizes that they don’t have it so bad during the other fifty-one weeks of the year.

The trip to the coast from the Susquehanna valley was a day-long journey. Back then, four-lane highways were few beyond the cities of the northeast corridor and traffic jams stretched for miles. Cars frequently overheated and steam rolled from beneath the hoods of those stopped to cool down. There were even 55-gallon drums of non-potable water positioned at known choke points along some of the state roads so that motorists could top off their radiators and proceed on. Within these back-ups there were many Volkswagen Beetles pausing along the side of the road with the rear hood propped up. Their air-cooled engines would overheat on a hot day if the car wasn’t kept moving. But, despite the setbacks, all were motivated to continue. In time, with perseverance, the smell of saltmarsh air was soon rolling in the windows. Our destination was near.

At the shore, priority one was to spend plenty of time at the beach. Sunbathers lathered up with various concoctions of oils and moisturizers, including my personal favorite, cocoa butter, then they broiled themselves in the raging rays of the fusion-reaction furnace located just eight light-minutes away. Reflected from the white sand and ocean surf, the flaming orb’s blinding light did a thorough job of cooking all the thousands of oil-basted sun worshippers packing the tidal zone for miles and miles. You could smell the hot cocoa butter in the summer air as they burned. Well, maybe not, but you could smell something there.

By now, you’re probably saying, “Hey, why weren’t you idiots wearing protection from the sun’s harmful U.V. rays?”

Good question. Uncle Tyler Dyer reminds me that back in the sixties, a sunscreen was a shade hung to cover a window. He continued, “Man, the only sun block we had was a beach ball that happened to pass between us and the sun.”

During several of our summertime beach visits in the early 1970s, we got a different sort of oil treatment—tar balls. We never noticed the things until we got out of the water. Playing around at the tide line and taking a tumble in the surf from time to time, we must have picked them up when we rolled in the sand.

Uncle Ty wasn’t happy, “Man, they’re sticking all over our legs and feet, and look at your swim trunks, they’re ruined. And look in the sand, they’re everywhere.” The event was one of the seeds that would in time grow into Uncle Ty’s fundamental distrust of corporate culture.

Looking around, tar balls were all over everyone who happened to be near the water. Rumor on the beach was that they came from ships that passed by offshore earlier in the day. The probable source was the many oil spills that had occurred in the Mid-Atlantic region in those years. During the first six months of 1973 alone, there were over 800 oil spills there. Three hundred of those spills occurred in the waters surrounding New York City. The largest, almost half a million gallons, occurred in New York Harbor when a cargo ship collided with the tanker “Esso Brussels”. Forty percent of that spill burned in the fire that followed the mishap, the remainder entered the environment.

When it was time to clean up, we slowly removed the tar from our legs and feet by rubbing it away with a rag soaked in charcoal lighter fluid or gasoline. Needless to say, our skin turned redder than it had already been from sunburn.

After a full day in the surf, we’d be on our way back to our “home base” for summer vacation, a campground nestled somewhere in the pines on the mainland side of the tidal marshes behind our beach’s barrier island. There, we’d shake the sand out of our trunks and savor the feeling of dry clothing. As the sun set, the smoke, flicker, and crackle of dozens of campfires filled the spaces between the tents and camping trailers. Colored lights strung around awnings dazzled sun-weary eyes as night descended across the landscape. We’d commence the process of incinerating some marshmallows soon after. Then, sometime while we were roasting our weenies and warming our buns, we’d hear it.

His device didn’t have a very good muffler. It sounded like a rusty old lawn mower running on the back of a rusty old truck that didn’t sound much better. And you could see the cloud rising above the campsites around the corner as he approached. It was the mosquito man, come to rid the place of pesky nocturnal biting insects. Behind him, always, were young boys on bicycles riding in and out of the fog of insecticide that rolled from the back of the truck.

One was wise to quickly eat your campfire food and put the rest away before the fog rolled in. You had just minutes to choke down that burned up hot dog. Then the sense of urgency was gone. Everyone just sat around at picnic tables and on lawn chairs bathing in the airborne cloud. A thin layer of insecticide rubbed into the skin along with the liberal doses of Noxzema being applied to soothe sunburn pain will get you through the night just fine.

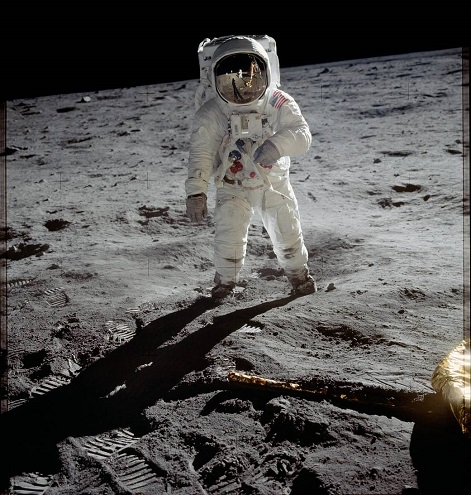

Perhaps the most memorable event to occur during our summer vacations happened at the moment of this writing, fifty years ago.

We were vacationing in a campground in southern New Jersey. Our family and the family of my dad’s co-worker gathered in a mosquito-mesh tent surrounding a small black-and-white television. An extension cord was strung to a receptacle on a nearby post, and the cathode ray tube produced the familiar picture of glowing blue tones to illuminate the otherwise dark scene. There was constant experimentation with the whip antenna to try to get a visible signal. There were no local UHF broadcasters and the closest VHF television stations were in Philadelphia, so the picture constantly had “snow” diminishing its already poor clarity. But we could see it, and I’ll never forget it.

SOURCES

Andelman, David A. “Oil Spills Here Total 300 in ’73”. The New York Times. August 8, 1973. p.41.

Cortright, Edgar M. (Editor). 1975. Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, DC.