Photo of the Day

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Flights of southbound Broad-winged Hawks have joined those of other Neotropical migrants to thrill observers with spectacular numbers. In recent days, thousands have been seen and counted at many of the regions hawkwatching stations. Now is the time to check it out!

Other diurnal migrants are on the move as well…

Adding to the diversity of sightings, there are these diurnal raptors arriving in the area right now…

For more information and directions to places where you can observe migrating hawks and other birds, be certain to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper” tab at the top of this page.

There’s something in the air tonight—and it’s more than just a cool comfortable breeze.

It’s a major nocturnal movement of southbound Neotropical birds. At daybreak, expect a fallout of migrants, particularly songbirds, in forests and thickets throughout the region. Warblers, vireos, flycatchers, thrushes, Scarlet Tanagers, and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks pass through in mid-September each year, so be on the lookout!

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection has issued a “drought watch” for much of the state’s Susquehanna basin including Dauphin, Lebanon, and Perry Counties—plus those counties to their north. Residents are asked to conserve water in the affected areas.

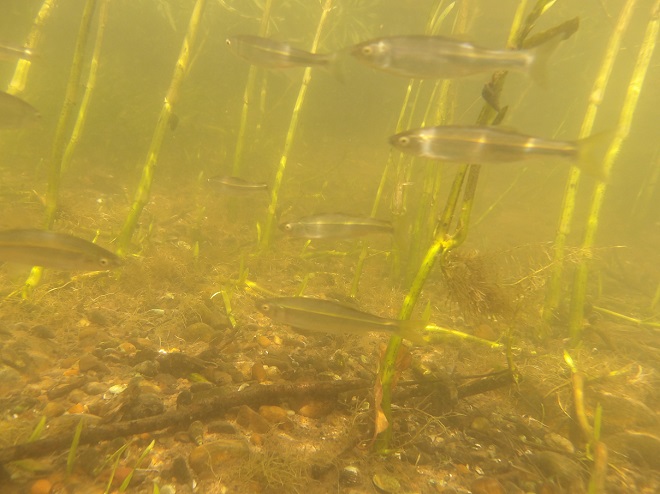

First there was the Nautilus. Then there was the Seaview. And who can forget the Yellow Submarine? Well, now there’s the S. S. Haldeman, and today we celebrated her shakedown cruise and maiden voyage. The Haldeman is powered by spent fuel that first saw light of day near Conewago Falls at a dismantled site that presently amounts to nothing more than an electrical substation. Though antique in appearance, the vessel discharges few emissions, provided there aren’t any burps or hiccups while underway. So, climb aboard as we take a cruise up the Susquehanna at periscope depth to have a quick look around!

Watertight and working fine. Let’s flood the tanks and have a peek at the benthos. Dive, all dive!

We’re finding that a sonar “pinger” isn’t very useful while running in shallow water. Instead, we should consider bringing along a set of Pings—for the more than a dozen golf balls seen on the river bottom. It appears they’ve been here for a while, having rolled in from the links upstream during the floods. Interestingly, several aquatic species were making use of them.

Well, it looks like the skipper’s tired and grumpy, so that’s all for now. Until next time, bon voyage!

Over the coming six weeks or more, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds will be feeding throughout the daylight hours to fuel their long migration to the tropics for winter. With plenty of adult and juvenile birds around, it’s the best time of year to get a better look at them by putting up a feeder.

You may already know the basics—hang the feeder near flower beds if you have them, keep it filled with a mixture of one part sugar to four parts water, and fill the little ant trap with fresh water. And you may know too, that to provide for the birds’ safety you should avoid hanging your feeder near plate glass windows and you should keep it high enough to avoid ambushes by any predators which may be hiding below.

Now here’s a hummingbird feeding basic (a bird feeding basic really) that you may not have considered. For every hummingbird feeder you intend to have filled and hanging in your garden, have a second one cleaned and air-drying to replace it when it’s time to refill. Why? Sugar water, like bird seed when it gets wet, is an excellent media for growing bacteria, molds, and other little beasties that can make birds (and people) sick. In the summer heat, these microorganisms grow much faster than they would in the wintertime, so diligence is necessary. Regularly, on a daily basis ideally, each feeder in your garden should be taken down and replaced with a clean, dry feeder filled with fresh sugar water mixture. The cleaning process should include dumping of the feeder’s contents followed by a thorough scrubbing with soapy water to remove any food residues that, if left remaining, can provide nourishment for growing bacteria. Next, the feeder should be rinsed with clean water to wash away soap and debris. You can sanitize the feeder if you wish, but it is more important to allow it to air-dry until its next use. Depriving mold, bacteria, and other microbes of moisture is a critical step in the process of eliminating them as a health hazard.

A Note of Caution: To avoid cross contaminating the utensils and space you use for preparing and serving meals, it’s important to have a separate work area with brushes, buckets, and other equipment dedicated only to bird feeder cleaning and drying.

So, let’s review. If you’re going to have a hummingbird feeder filled with nectar hanging in your garden, you need a second one—clean, dry, and ready to replace it.

If you’d like to attract more than one hummingbird at a time to your garden, you may want to place a second feeder where the territorial little bird claiming the first as its own can’t see it. Then you’ll need four feeders—two hanging in the garden and two that are clean, dry, and ready to be filled with fresh sugar water to use as replacements.

If you’re in a rural area with good habitat, you may have four or more feeders around your refuge. You’ll need a replacement feeder for each.

Remember, keep your feeders clean and filled with fresh nectar and you’ll be all set to enjoy the Ruby-throated Hummingbirds of late summer. Then watch closely for the cold-hardy western species that visit the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed beginning in October. The occurrence of at least one of these rarities in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed each autumn is now something of a regular event.

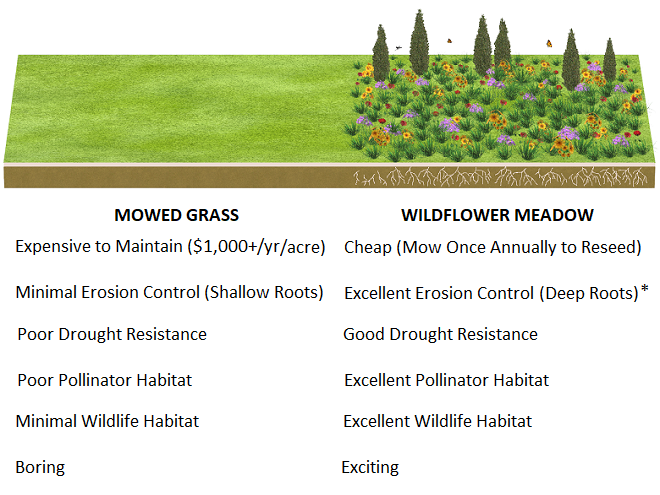

This month, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (I.U.C.N.) added the Migratory Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) to its “Red List of Threatened Species”, classifying it as endangered. Perhaps there is no better time than the present to have a look at the virtues of replacing areas of mowed and manicured grass with a wildflower garden or meadow that provides essential breeding and feeding habitat for Monarchs and hundreds of other species of animals.

If you’re not quite sure about finally breaking the ties that bind you to the cult of lawn manicuring, then compare the attributes of a parcel maintained as mowed grass with those of a space planted as a wildflower garden or meadow. In our example we’ve mixed native warm season grasses with the wildflowers and thrown in a couple of Eastern Red Cedars to create a more authentic early successional habitat.

Still not ready to take the leap. Think about this: once established, the wildflower planting can be maintained without the use of herbicides or insecticides. There’ll be no pesticide residues leaching into the soil or running off during downpours. Yes friends, it doesn’t matter whether you’re using a private well or a community system, a wildflower meadow is an asset to your water supply. Not only is it free of man-made chemicals, but it also provides stormwater retention to recharge the aquifer by holding precipitation on site and guiding it into the ground. Mowed grass on the other hand, particularly when situated on steep slopes or when the ground is frozen or dry, does little to stop or slow the sheet runoff that floods and pollutes streams during heavy rains.

What if I told you that for less than fifty bucks, you could start a wildflower garden covering 1,000 square feet of space? That’s a nice plot 25′ x 40′ or a strip 10′ wide and 100′ long along a driveway, field margin, roadside, property line, swale, or stream. All you need to do is cast seed evenly across bare soil in a sunny location and you’ll soon have a spectacular wildflower garden. Here at the susquehannawildllife.net headquarters we don’t have that much space, so we just cast the seed along the margins of the driveway and around established trees and shrubs. Look what we get for pennies a plant…

Here’s a closer look…

All this and best of all, we never need to mow.

Around the garden, we’ve used a northeast wildflower mix from American Meadows. It’s a blend of annuals and perennials that’s easy to grow. On their website, you’ll find seeds for individual species as well as mixes and instructions for planting and maintaining your wildflower garden. They even have a mix specifically formulated for hummingbirds and butterflies.

Nothing does more to promote the spread and abundance of non-native plants, including invasive species, than repetitive mowing. One of the big advantages of planting a wildflower garden or meadow is the opportunity to promote the growth of a community of diverse native plants on your property. A single mowing is done only during the dormant season to reseed annuals and to maintain the meadow in an early successional stage—preventing reversion to forest.

For wildflower mixes containing native species, including ecotypes from locations in and near the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, nobody beats Ernst Conservation Seeds of Meadville, Pennsylvania. Their selection of grass and wildflower seed mixes could keep you planting new projects for a lifetime. They craft blends for specific regions, states, physiographic provinces, habitats, soils, and uses. Check out these examples of some of the scores of mixes offered at Ernst Conservation Seeds…

We’ve used their “Showy Northeast Native Wildflower and Grass Mix” on streambank renewal projects with great success. For Monarchs, we really recommend the “Butterfly and Hummingbird Garden Mix”. It includes many of the species pictured above plus “Fort Indiantown Gap” Little Bluestem, a warm-season grass native to Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, and milkweeds (Asclepias), which are not included in their northeast native wildflower blends. More than a dozen of the flowers and grasses currently included in this mix are derived from Pennsylvania ecotypes, so you can expect them to thrive in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

In addition to the milkweeds, you’ll find these attractive plants included in Ernst Conservation Seed’s “Butterfly and Hummingbird Garden Mix”, as well as in some of their other blends.

Why not give the Monarchs and other wildlife living around you a little help? Plant a wildflower garden or meadow. It’s so easy, a child can do it.

On these hot and steamy days of summer, I get to thinking about how great it would be to have a swimming pool. Maybe I would take a little dip, you know, just to cool down. But when I really get to thinking about it, I just might do what the professor has done with his pool.

Or maybe I would do what this lady did with her pool.

Wouldn’t you?

You’ve heard and read it before—native plants do the best job of providing sustenance for our indigenous wildlife. Let’s say you have a desire to attract hummingbirds to your property and you want to do it without putting up feeders. Well, you’ll need native plants that provide tubular flowers from which these hovering little birds can extract nectar. Place enough of them in conspicuous locations and you’ll eventually see hummingbirds visiting during the summer months. If you have a large trellis, pole, or fence, you might plant a Trumpet Vine, also known as Trumpet Creeper. They become adorned with an abundance of big red-orange tubular flowers that our Ruby-throated Hummingbirds just can’t resist. For consistently bringing hummingbirds to the garden, Trumpet Vine may be the best of the various plants native to the Mid-Atlantic States.

There is a plant, not particularly native to our area but native to the continent, that even in the presence of Trumpet Vine, Pickerelweed, Partridge Pea, and other reliable hummingbird lures will outperform them all. It’s called Mexican Cigar (Cuphea ignea) or Firecracker Plant. Its red and yellow tubular flowers look like a little cigar, often with a whitish ash at the tip. Its native range includes some of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird’s migration routes and wintering grounds in Mexico and the Caribbean Islands, where they certainly are familiar with it.

This morning in the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters garden, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird seen in the following set of images extracted nectar from the Mexican Cigar blossoms exclusively. It ignored the masses of showy Trumpet Vine blooms and other flowers nearby—as the hummers that stop by usually do when Cuphea is offered.

Some garden centers still have Mexican Cigar plants available. You can grow them in pots or baskets, then bring them inside before frost to treat them as a house plant through the winter. Give the plants a good trim sometime before placing them outside when the weather warms in May. You’ll soon have Ruby-throated Hummingbirds visiting again for the summer.

Some garden centers still have Mexican Cigar plants available. You can grow them in pots or baskets, then bring them inside before frost to treat them as a house plant through the winter. Give the plants a good trim sometime before placing them outside when the weather warms in May. You’ll soon have Ruby-throated Hummingbirds visiting again for the summer.