Here are a few more late-season migrants you might currently see passing through the lower Susquehanna valley. Where adequate food and cover are available, some may remain into part or all of the winter…

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Here are a few more late-season migrants you might currently see passing through the lower Susquehanna valley. Where adequate food and cover are available, some may remain into part or all of the winter…

While the heat and humidity of early summer blankets the region, Brood XIV Periodical Cicadas are wrapping up their courtship and breeding cycle for 2025. We’ve spent the past week visiting additional sites in and near the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where their emergence is evident.

We begin in York County just to the west of the river and Conewago Falls in mostly forested terrain located just southeast of Gifford Pinchot State Park. Within this area, often called the Conewago Hills, a very localized population of cicadas could be heard in the woodlands surrounding the scattered homes along Bull Road. Despite the dominant drone of an abundance of singing Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas, we were able to hear and record the courtship song of a small number of the rare Little Seventeen-year Cicadas. Their lawn sprinkler-like pulsating songs help mate-seeking males penetrate the otherwise overwhelming chorus of the Pharaoh cicadas in the area.

From the Conewago Hills we moved northwest into the section of southern Cumberland County known as South Mountain. Here, Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas were widespread in ridgetop forests along the Appalachian Trail, particularly in the area extending from Long Mountain in the east through Mount Holly to forests south of King’s Gap Environmental Education Center in the west.

While on South Mountain, we opted for a side trip into the neighboring Potomac watershed of Frederick County, Maryland, where these hills ascend to greater altitude and are known as the Blue Ridge Mountains, a name that sticks with them all the way through Shenandoah National Park, the Great Smoky Mountains, and to their southern terminus in northwestern Georgia. We found a fragmented emergence of Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas atop the Catoctin Mountain section of the Blue Ridge just above the remains of Catoctin Furnace, again on lands that had been timbered to make charcoal to fuel iron production prior to their protection as vast expanses of forest.

Back in Pennsylvania, we’re on our way to the watersheds of the northernmost tributaries of the lower Susquehanna’s largest tributary, the Juniata River. There, we found Brood XIV cicadas more widespread and in larger numbers than occurred at previous sites. Both Pharaoh and Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas were seen and heard along Jack’s Mountain and the Kishacoquillas Creek north of Lewistown/Burnham in Mifflin County. To the north of the Kishacoquillas Valley and Stone Mountain in northernmost Huntingdon County, the choruses of the two species were again widespread, particularly along the forest edges in Greenwood Furnace State Park, Rothrock State Forest, and adjacent areas of the Standing Stone Creek watershed.

Within the last 48 hours, we visited one last location in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where Brood XIV Periodical Cicadas have emerged during 2025. In the anthracite coal country of Northumberland County, a flight of Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas is nearing its end. We found them to be quite abundant in forested areas of Zerbe Run between Big and Little Mountains around Trevorton and on the wooded slopes of Mahanoy Mountain south of nearby Shamokin. Line Mountain south of Gowen City had a substantial emergence as well.

To chart our travels, we’ve put together this map plotting the occurrence of significant flights of Periodical Cicadas during the 2025 emergence. Unlike the more densely distributed Brood X cicadas of 2021, the range of Brood XIV insects is noticeably fragmented, even in areas that are forested. We found it interesting how frequently we found Brood XIV cicadas on lands used as sources of lumber to make charcoal for fueling nineteenth-century iron furnace operations.

Well, that’s a wrap. Please don’t forget to check out our new Cicadas page by clicking the “Cicadas” tab at the top of this page. Soon after the Periodical Cicadas are gone, the annual cicadas will be emerging and our page can help you identify the five species found regularly in the lower Susquehanna valley. ‘Til next time, keep buzzing!

Here’s a short preview of some of the finds you can expect during an outing in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s forests this week…

After repeatedly hearing the songs of these Neotropical migrants from among the foliage, we were finally able to get a look at them—but it required persistent effort.

Sometimes we have to count ourselves lucky if we see just one in five, ten, or even twenty of the birds we hear in the cover of the forest canopy or thicket. But that’s what makes this time of year so rewarding for the dedicated observer. The more time you spend out there, the more you’ll eventually discover. See you afield!

Here’s a look at six native shrubs and trees you can find blooming along forest edges in the lower Susquehanna valley right now.

Local old timers might remember hearing folklore that equates the northward advance of the blooming of the Flowering Dogwoods with the progress of the American Shad’s spring spawning run up the river. While this is hardly a scientific proclamation, it is likely predicated on what had been some rather consistent observation prior to the construction of the lower Susquehanna’s hydroelectric dams. In fact, we’ve found it to be a useful way to remind us that it’s time for a trip to the river shoreline below Conowingo Dam to witness signs of the spring fish migration each year. We’re headed that way now and will summarize our sightings for you in days to come.

Here are five common forest flowers that the average visitor to these environs may easily overlook during an early April visit.

Be certain to get out and enjoy this year’s blooming seasons of our hundreds of varieties of flowering plants. But, particularly when it comes to native species,…

Our wildlife has been having a tough winter. The local species not only contend with cold and stormy weather, but they also need to find food and shelter in a landscape that we’ve rendered sterile of these essentials throughout much of the lower Susquehanna valley’s farmlands, suburbs, and cities.

Planting trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses that benefit our animals can go a long way, often turning a ho-hum parcel of property into a privately owned oasis. Providing places for wildlife to feed, rest, and raise their young can help assure the survival of many of our indigenous species. With a little dedication, you can be liberated from the chore of manicuring a lawn and instead spend your time enjoying the birds, mammals, insects, and other creatures that will visit your custom-made habitat.

Fortunately for us, our local county conservation districts are again conducting springtime tree sales offering a variety of native and beneficial cultivated plants at discount prices. Listed here are links to information on how to pre-order your plants for pickup in April. Click away to check out the species each county is offering in 2025!

Cumberland County Conservation District Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 21, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 24, 2025 or Friday, April 25, 2025

Dauphin County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Monday, March 17, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 24, 2025 or Friday, April 25, 2025

Franklin County Conservation District Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Wednesday, March 19, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 24, 2025

Lancaster County Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 7, 2025

Pickup on: Friday, April 11, 2025

Lebanon County Conservation District Tree and Plant Sale—

Orders due by: Monday, March 3, 2025

Pickup on: Friday, April 18, 2025

York County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: March 15, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 10, 2025

If you live in Adams County, Pennsylvania, you may be eligible to receive free trees and shrubs for your property from the Adams County Planting Partnership (Adams County Conservation District and the Watershed Alliance of Adams County). These trees are provided by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Keystone 10-Million Trees Partnership which aims to close a seven-year project in 2025 by realizing the goal of planting 10 million trees to protect streams by stabilizing soils, taking up nutrients, reducing stormwater runoff, and providing shade. If you own property located outside of Adams County, but still within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed (which includes all of the Susquehanna, Juniata, and Potomac River drainages), you still may have an opportunity to get involved. Contact your local county conservation district office or watershed organization for information.

We hope you’re already shopping. Need help making your selections? Click on the “Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines” tab at the top of this page to check out Uncle Tyler Dyer’s leaf collection. He has most of the species labelled with their National Wetland Plant List Indicator Rating. You can consult these ratings to help find species suited to the soil moisture on your planting site(s). For example: if your site has sloped upland ground and/or the soils sometimes dry out in summer, select plants with a rating such as UPL or FACU. If your planting in soils that remain moist or wet, select plants with the OBL or FACW rating. Plants rated FAC are generally adaptable and can usually go either way, but may not thrive or survive under stressful conditions in extremely wet or dry soils.

NATIONAL WETLAND PLANT LIST INDICATOR RATING DEFINITIONS

Using these ratings, you might choose to plant Pin Oaks (FACW) and Swamp White Oaks (FACW) in your riparian buffer along a stream; Northern Red Oaks (FACU) and White Oaks (FACU) in the lawn or along the street, driveway, or parking area; and Chestnut Oaks (UPL) on your really dry hillside with shallow soil. Give it a try.

During the past week, Uncle Tyler Dyer has been out searching for autumn leaves to add to his collection. One of the species he had not encountered in previous outings was the American Elm (Ulmus americana), so he made a special trip to see a rare mammoth specimen in a small neighborhood park (Park Place) along Chestnut Street between 5th and Quince Streets in Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

There’s still time to get out and see autumn foliage. With warmer weather upon us—at least temporarily—it’s a good time to go for a stroll. Who knows, you might find some spectacular leaves like these collected by Uncle Ty earlier this week. All were found adorning native plants!

Clear, cool nights have provided ideal flight conditions for nocturnal Neotropical migrants and other southbound birds throughout the week. Fix yourself a drink and a little snack, then sit down and enjoy this set of photographs that includes just some of the species we found during sunrise feeding frenzies atop several of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s ridges. Hurry up, because here they come…

The migration is by no means over; it has only just begun. So plan to visit a local hawkwatch or other suitable ridgetop in coming weeks. Arrive early (between 7 and 8 AM) to catch a glimpse of a nocturnal migrant fallout, then stay through the day to see the hundreds, maybe even thousands, of Broad-winged Hawks and other diurnal raptors that will pass by. It’s an experience you won’t forget.

Be certain to click the “Birds” tab at the top of this page for a photo guide to the species you’re likely to see passing south through the lower Susquehanna valley in coming months. And don’t forget to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab to find a hawk-counting station near you.

During the past week, we’ve been exploring wooded slopes around the lower Susquehanna region in search of recently arrived Neotropical birds—particularly those migrants that are singing on breeding territories and will stay to nest. Coincidentally, we noticed a good diversity of species in areas where tent caterpillar nests were apparent.

Here’s a sample of the variety of Neotropical migrants we found in areas impacted by Eastern Tent Caterpillars. All are arboreal insectivores, birds that feed among the foliage of trees and shrubs searching mostly for insects, their larvae, and their eggs.

In the locations where these photographs were taken, ground-feeding birds, including those species that would normally be common in these habitats, were absent. There were no Gray Catbirds, Carolina Wrens, American Robins or other thrushes seen or heard. One might infer that the arboreal insectivorous birds chose to establish nesting territories where they did largely due to the presence of an abundance of tent caterpillars as a potential food source for their young. That could very well be true—but consider timing.

So why do we find this admirable variety of Neotropical bird species nesting in locations with tent caterpillars? Perhaps it’s a matter of suitable topography, an appropriate variety of native trees and shrubs, and an attractive opening in the forest.

Here in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the presence of Eastern Tent Caterpillar nests can often be an indicator of a woodland opening, natural or man-made, that is being reforested by Black Cherry and other plants which improve the botanical richness of the site. For numerous migratory Neotropical species seeking favorable places to nest and raise young, these regenerative areas and the forests surrounding them can be ideal habitat. For us, they can be great places to see and hear colorful birds.

As week-old snow and ice slowly disappears from the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed landscape, we ventured out to see what might be lurking in the dense clouds of fog that for more than two days now have accompanied a mid-winter warm spell.

If scenes of a January thaw begin to awaken your hopes and aspirations for all things spring, then you’ll appreciate this pair of closing photographs…

With the earth at perihelion (its closest approach to the sun) and with our home star just 27 degrees above the horizon at midday, bright low-angle light offered the perfect opportunity for doing some wildlife photography today. We visited a couple of grasslands managed by the Pennsylvania Game Commission to see what we could find…

Where should you go this weekend to see vibrantly colored foliage in our region? Where are there eye-popping displays of reds, oranges, yellows, and greens without so much brown and gray? The answer is Michaux State Forest on South Mountain in Adams, Cumberland, and Franklin Counties.

South Mountain is the northern extension of the Blue Ridge Section of the Ridge and Valley Province in Pennsylvania. Michaux State Forest includes much of the wooded land on South Mountain. Within or adjacent to its borders are located four state parks: King’s Gap Environmental Education Center, Pine Grove Furnace State Park, Caledonia State Park, and Mont Alto State Park. The vast network of trails on these state lands includes the Appalachian Trail, which remains in the mountainous Blue Ridge Section all the way to its southern terminus in Georgia.

If you want a closeup look at the many species of trees found in Michaux State Forest, and you want them to be labeled so you know what they are, a stop at the Pennsylvania State University’s Mont Alto arboretum is a must. Located next door to Mont Alto State Park along PA 233, the Arboretum at Penn State Mont Alto covers the entire campus. Planting began on Arbor Day in 1905 shortly after establishment of the Pennsylvania State Forest Academy at the site in 1903. Back then, the state’s “forests” were in the process of regeneration after nineteenth-century clear cutting. These harvests balded the landscape and left behind the combustible waste which fueled the frequent wildfires that plagued reforestation efforts for more than half a century. The academy educated future foresters on the skills needed to regrow and manage the state’s woodlands.

Online resources can help you plan your visit to the Arboretum at Penn State Mont Alto. More than 800 trees on the campus are numbered with small blue tags. The “List of arboretum trees by Tag Number” can be downloaded to tell you the species or variety of each. The interactive map provides the locations of individual trees plotted by tag number while the Grove Map displays the locations of groups of trees on the campus categorized by region of origin. A Founder’s Tree Map will help you find some of the oldest specimens in the collection and a Commemorative Tree Map will help you find dedicated trees. There is also a species list of the common and scientific tree names.

The autumn leaves will be falling fast, so make it a point this weekend to check out the show on South Mountain.

Here’s a look at some native plants you can grow in your garden to really help wildlife in late spring and early summer.

Let’s have a look at some of the magnificent native wildflowers blooming on this Mother’s Day in forests and thickets throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Aren’t they spectacular?

Why not take a stroll to have a look at these and other plants you can find growing along a nearby woodland trail? You could check out some place new and get a little exercise too!

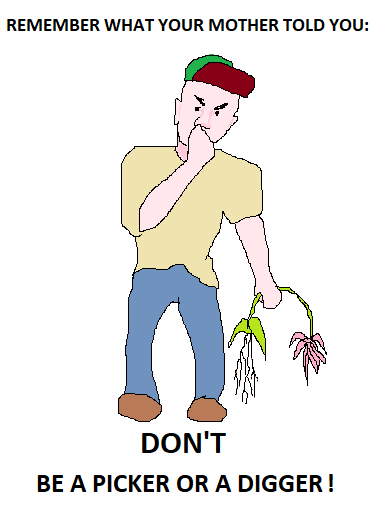

If you go, please tread lightly, take your camera, mind your manners, and…

Let’s take a quiet stroll through the forest to have a look around. The spring awakening is underway and it’s a marvelous thing to behold. You may think it a bit odd, but during this walk we’re not going to spend all of our time gazing up into the trees. Instead, we’re going to investigate the happenings at ground level—life on the forest floor.

There certainly is more to a forest than the living trees. If you’re hiking through a grove of timber getting snared in a maze of prickly Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) and seeing little else but maybe a wild ungulate or two, then you’re in a has-been forest. Logging, firewood collection, fragmentation, and other man-made disturbances inside and near forests take a collective toll on their composition, eventually turning them to mere woodlots. Go enjoy the forests of the lower Susquehanna valley while you still can. And remember to do it gently; we’re losing quality as well as quantity right now—so tread softly.

Thoughts of October in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed bring to mind scenes of brilliant fall foliage adorning wooded hillsides and stream courses, frosty mornings bringing an end to the growing season, and geese and other birds flying south for the winter.

The autumn migration of birds spans a period equaling nearly half the calendar year. Shorebirds and Neotropical perching birds begin moving through as early as late July, just as daylight hours begin decreasing during the weeks following their peak at summer solstice in late June. During the darkest days of the year, those surrounding winter solstice in late December, the last of the southbound migrants, including some hawks, eagles, waterfowl, and gulls, may still be on the move.

During October, there is a distinct change in the list of species an observer might find migrating through the lower Susquehanna valley. Reduced hours of daylight and plunges in temperatures—particularly frost and freeze events—impact the food sources available to birds. It is during October that we say goodbye to the Neotropical migrants and hello to those more hardy species that spend their winters in temperate climates like ours.

The need for food and cover is critical for the survival of wildlife during the colder months. If you are a property steward, think about providing places for wildlife in the landscape. Mow less. Plant trees, particularly evergreens. Thickets are good—plant or protect fruit-bearing vines and shrubs, and allow herbaceous native plants to flower and produce seed. And if you’re putting out provisions for songbirds, keep the feeders clean. Remember, even small yards and gardens can provide a life-saving oasis for migrating and wintering birds. With a larger parcel of land, you can do even more.

She ate only toaster pastries…that’s it…nothing else. Every now and then, on special occasions, when a big dinner was served, she’d have a small helping of mashed potatoes, no gravy, just plain, thank you. She received all her nutrition from several meals a week of macaroni and cheese assembled from processed ingredients found in a cardboard box. It contains eight essential vitamins and minerals, don’t you know? You remember her, don’t you?

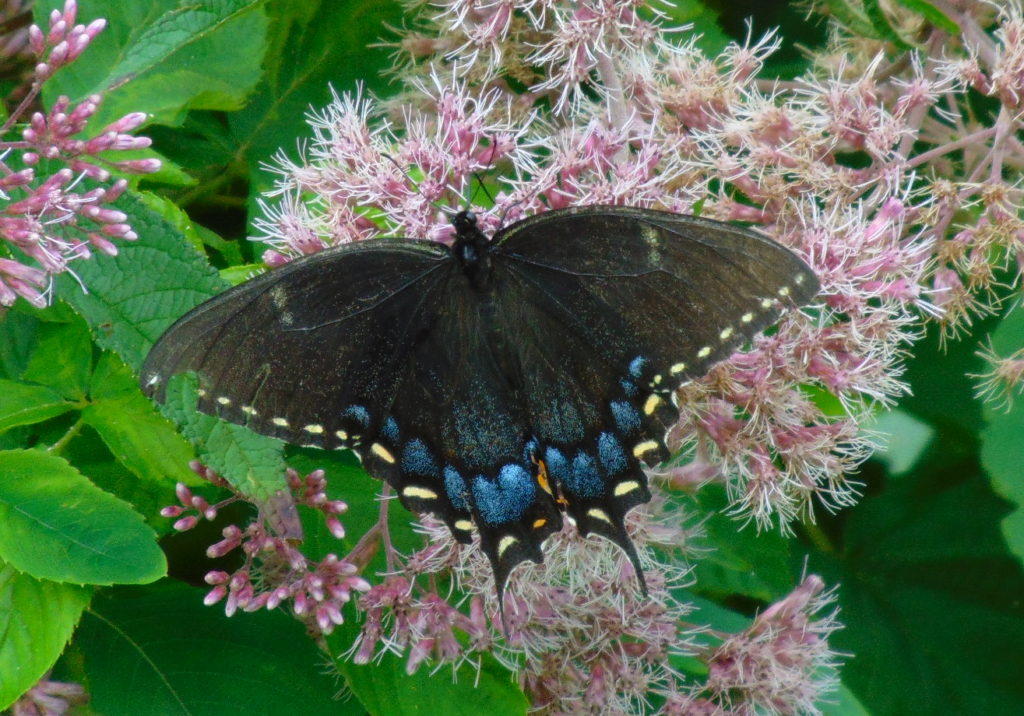

Adult female butterflies must lay their eggs where the hatched larvae will promptly find the precise food needed to fuel their growth. These caterpillars are fussy eaters, with some able to feed upon only one particular species or genus of plant to grow through the five stages, the instars, of larval life. The energy for their fifth molt into a pupa, known as a chrysalis, and metamorphosis into an adult butterfly requires mass consumption of the required plant matter. Their life cycle causes most butterflies to be very habitat specific. These splendid insects may visit the urban or suburban garden as adults to feed on nectar plants, however, successful reproduction relies upon environs which include suitable, thriving, pesticide-free host plants for the caterpillars. Their survival depends upon more than the vegetation surrounding the typical lawn will provide.

The Monarch (Danaus plexippus), a butterfly familiar in North America for its conspicuous autumn migrations to forests in Mexico, uses the milkweeds (Asclepias) almost exclusively as a host plant. Here at Conewago Falls, wetlands with Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and unsprayed clearings with Common Milkweed (A. syriaca) are essential to the successful reproduction of the species. Human disturbance, including liberal use of herbicides, and invasive plant species can diminish the biomass of the Monarch’s favored nourishment, thus reducing significantly the abundance of the migratory late-season generation.

Butterflies are good indicators of the ecological health of a given environment. A diversity of butterfly species in a given area requires a wide array of mostly indigenous plants to provide food for reproduction. Let’s have a look at some of the species seen around Conewago Falls this week…

The spectacularly colorful butterflies are a real treat on a hot summer day. Their affinity for showy plants doubles the pleasure.

By the way, I’m certain by now you’ve recalled that fussy eater…and how beautiful she grew up to be.

SOURCES

Brock, Jim P., and Kaufman, Kenn. 2003. Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.