Photo of the Day

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

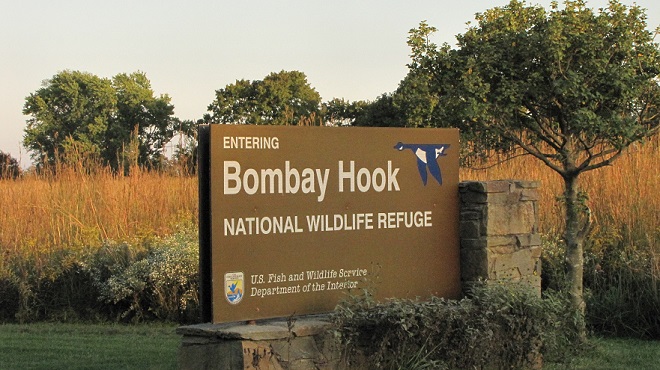

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

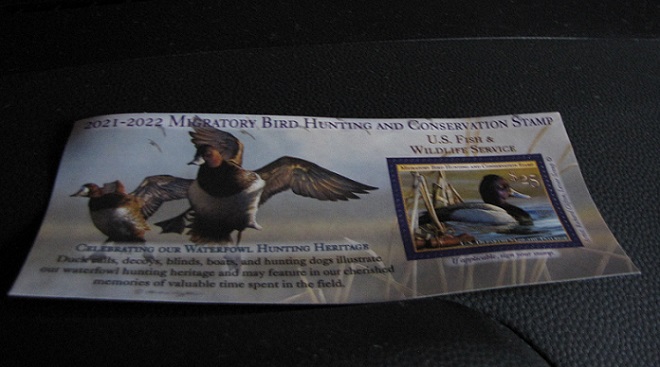

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

It’s been more than a year and a half since Uncle Tyler Dyer has been on one of our outings. He’s been laying low, keeping to himself—to protect his health. So he was quite excited when we made our way to the Delaware coast to have a look at some marine and beach life at Cape Henlopen State Park.

Uncle Ty hadn’t visited the Atlantic shoreline here for almost two decades, and he was more than a bit startled at what he saw…

A nearly sterile beach might be delightful for barefoot sunbathers and the running of the dogs, but Uncle Ty isn’t the barefoot type. He likes his sandals and a slow peaceful stroll with plenty of flora and fauna to have a look at. We could tell he was getting bored. So we headed home.

Along the way, Uncle Ty asked to stop at the Post Office. He wanted to get a stamp. Thinking he was going to fire off a terse letter of protest to the powers that be about what he saw at the beach, we obliged.

Soon, Uncle Ty trotted down the steps of the Post Office with his stamp.

Uncle Ty bought a duck stamp, so naturally we asked him when he decided to take up hunting. He explained, “Man, I gave that stuff up when I was thirteen. I’ve got the Thoreau/Walden mindset—hunting is something of an adolescent pursuit.”

It turns out Uncle Ty bought a duck stamp to support wetland acquisition and improvements, not only to benefit ducks and other wildlife living there, but to improve water quality. In Delaware, tidal estuary restoration work is underway at both the Prime Hook and Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuges on Delaware Bay. These projects will certainly enhance the salt marsh’s filtration capabilities and just might improve the populations of benthic life in the bay and adjacent ocean at Cape Henlopen.

Uncle Ty tossed the stamp atop the dashboard and we were again on our way, but we weren’t going directly home. We made a stop along the way. A stop we’ll share with you next time.

Each autumn, Eastern Golden Eagles transit the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed as they make their way from nesting sites in eastern Canada to wintering ranges in the mountains of the eastern United States. The majority of these birds make passage during late October and early November, so when a Golden Eagle is observed at a local hawk watch during the month of September, it is a notable event. So far in 2021, both Waggoner’s Gap Hawk Watch north of Carlisle and Second Mountain Hawk Watch at Fort Indiantown Gap have logged early-season Golden Eagles, the former on the seventeenth of September and the latter just yesterday.

To learn more about identifying Golden Eagles and other birds of prey, be certain to click the “Hawkwatchers Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Raptors” tab at the top of this page.

And for more specific information on Golden Eagles and how to determine their age, click the “Golden Eagle Aging Chart” tab at the top of this page.

Can it be that time already? Most Neotropical birds have passed through the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed on their way south and the hardier species that will spend our winter in the more temperate climes of the eastern United States are beginning to arrive.

Here’s a gallery of sightings from recent days…

Be sure to click on these tabs at the top of this page to find image guides to help you identify the dragonflies, birds, and raptors you see in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed…

See you next time!

The smoke has cleared—at least for now—and Broad-winged Hawks are being seen migrating across lower Susquehanna valley skies. Check out these daily counts from area hawk watches…

Additional Broad-winged Hawks are still working their way through the Mid-Atlantic States as they continue toward tropical wintering grounds. And there’s more. Numbers for a dozen other migratory hawk, eagle, and falcon species will peak between now and mid-November. Days following passage of a cold front are generally best—so do get out there and have a look!

You can check the daily hawk count numbers and find detailed information for lookout sites all across North America at hawkcount.org

And don’t forget to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper” tab at the top of this page to see a gallery of photos that can help you to identify, and possibly determine the age of, the many species of raptors that occur in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

During the coming two weeks, peak numbers of migrating Neotropical birds will be passing through the northeastern United States including the lower Susquehanna valley. Hawk watches are staffed and observers are awaiting big flights of Broad-winged Hawks—hoping to see a thousand birds or more in a single day.

Broad-winged hawks feed on rodents, amphibians, and a variety of large insects while on their breeding grounds in the forests of the northern United States and Canada. They depart early, journeying to wintering areas in Central and South America before frost robs them of a reliable food supply.

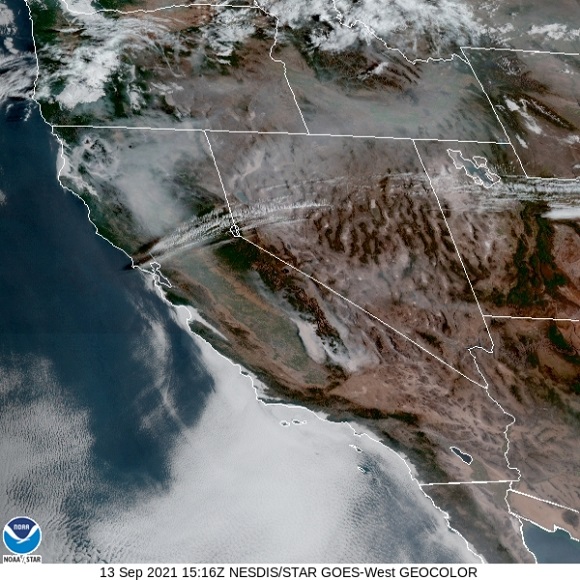

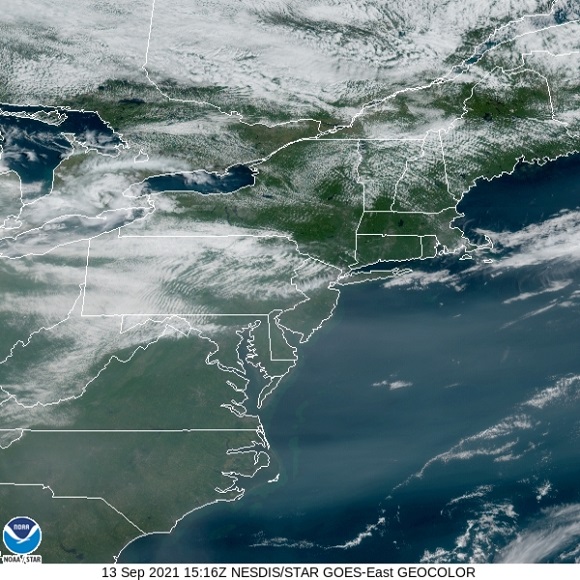

While migrating, Broad-winged Hawks climb to great altitudes on thermal updrafts and are notoriously difficult to see from ground level. Bright sunny skies with no clouds to serve as a backdrop further complicate a hawk counter’s ability to spot passing birds. Throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the coming week promises to be especially challenging for those trying to observe and census the passage of high-flying Broad-winged Hawks. The forecast of hot and humid weather is not so unusual, but the addition of smoke from fires in the western states promises to intensify the haze and create an especially irritating glare for those searching the skies for raptors.

It may seem gloomy for the mid-September flights in 2021, but hawk watchers are hardy types. They know that the birds won’t wait. So if you want to see migrating “Broad-wings” and other species, you’ve got to get out there and look up while they’re passing through.

These hawk watches in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are currently staffed by official counters and all welcome visitors:

—or you can just keep an eye on the sky from wherever you happen to be. And don’t forget to check the trees and shrubs because warbler numbers are peaking too! During recent days…

Neotropical birds are presently migrating south from breeding habitats in the United States and Canada to wintering grounds in Central and South America. Among them are more than two dozen species of warblers—colorful little passerines that can often be seen darting from branch to branch in the treetops as they feed on insects during stopovers in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Being nocturnal migrants, warblers are best seen first thing in the morning among sunlit foliage, often high in the forest canopy. After a night of flying, they stop to feed and rest. Warblers frequently join resident chickadees, titmice, and nuthatches to form a foraging flock that can contain dozens of songbirds. Migratory flycatchers, vireos, tanagers, and grosbeaks often accompany southbound warblers during early morning “fallouts”. Usually, the best way to find these early fall migrants is to visit a forest edge or thicket, particularly along a stream, a utility right-of-way, or on a ridge top. Then too, warblers and other Neotropical migrants are notorious for showing up in groves of mature trees in urban parks and residential neighborhoods—so look up!

Be sure to visit the Birds of Conewago Falls page by clicking the “Birds” tab at the top of this page. There, you’ll find photographs of the birds, including warblers and other Neotropical migrants, that you’re likely to encounter at locations throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

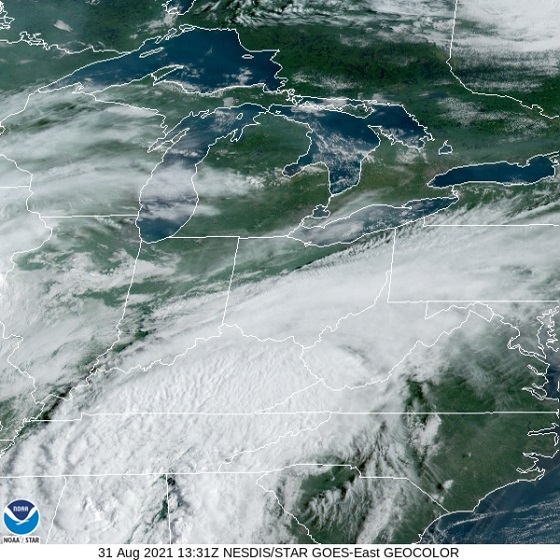

The remnants of Hurricane Ida are on their way to the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. After making landfall in Louisiana as a category 4 storm, Ida is on track to bring heavy rain to the Mid-Atlantic States beginning tonight.

Rainfall totals are anticipated to be sufficient to cause flooding in the lower Susquehanna basin. As much as six to ten inches of precipitation could fall in parts of the area on Wednesday.

Now would be a good time to get all your valuables and junk out of the floodways and floodplains. Move your cars, trucks, S.U.V.s, trailers, and boats to higher ground. Clear out the trash cans, playground equipment, picnic tables, and lawn furniture too. Get it all to higher ground. Don’t be the slob who uses a flood as a chance to get rid of tires and other rubbish by letting it just wash away.

Flooding not only has economic and public safety impacts, it is a source of enormous amounts of pollution. Chemical spills from inundated homes, businesses, and vehicles combine with nutrient and sediment runoff from eroding fields to create a filthy brown torrent that rushes down stream courses and into the Susquehanna. Failed and flooded sewage facilities, both municipal and private, not only pollute the water, but give it that foul odor familiar to those who visit the shores of the river after a major storm. And of course there is the garbage. The tons and tons of waste that people discard carelessly that, during a flood event, finds its way ever closer to the Susquehanna, then the Chesapeake, and finally the Atlantic. It’s a disgraceful legacy.

Now is your chance to do something about it. Go out right now and pick up the trash along the curb, in the street, and on the sidewalk and lawn—before it gets swept into your nearby stormwater inlet or stream. It’s easy to do, just bend and stoop. While you’re at it, clean up the driveway and parking lot too.

We’ll be checking to see how you did.

And remember, flood plains are for flooding, so get out of the floodplain and stay out.

Late August and early September is prime time to see migrating shorebirds as they pass through the lower Susquehanna valley during their autumn migration, which, believe it or not, can begin as early as late June. These species that are often assumed to spend their lives only near the seashore are regular visitors each fall as they make their way from breeding grounds in the interior of Canada to wintering sites in seacoast wetlands—many traveling as far south as Central and South America.

Low water levels on the Susquehanna River often coincide with the shorebird migration each year, exposing gravel and sand bars as well as vast expanses of muddy shorelines as feeding and resting areas for these traveling birds. This week though, rain from the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred arrived to increase the flow in the Susquehanna and inundate most of the natural habitat for shorebirds. Those on the move must either continue through the area without stopping or find alternate locations to loaf and find food.

The draining and filling of wetlands along the river and elsewhere in the region has left few naturally-occurring options. The Conejohela Flats south of Columbia offer refuge to many migrating sandpipers and their allies, the river level there being controlled by releases from the Safe Harbor Dam during all but the severest of floods. Shorebirds will sometimes visit flooded fields, but wide-open puddles and farmland resembling mudflats is more of springtime occurrence—preceding the planting and growth of crops. Well-designed stormwater holding facilities can function as habitat for sandpipers and other wildlife. They are worth checking on a regular basis—you never know what might drop in.

Right now, there is a new shorebird hot spot in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed—Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area. The water level in the main impoundment there has been drawn down during recent weeks to expose mudflats along the periphery of nearly the entire lake. Viewing from “Stop 1” (the roadside section of the lake in front of the refuge museum) is best. The variety of species and their numbers can change throughout the day as birds filter in and out—at times traveling to other mudflats around the lake where they are hidden from view. The birds at “Stop 1” are backlit in the morning with favorable illumination developing in the afternoon.

Have a look at a few of the shorebirds currently being seen at Middle Creek…

The aquatic environs at Middle Creek attract other species as well. Here are some of the most photogenic…

Some of of you may have been wondering why there has been no new content for a while. Well, rest assured that your editor has been replumbed and rewired by some of the best in the business during his recent stay at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and he is getting a little stronger every day. More field trips will be on the way soon!

In the meantime, have a look at some of the wide variety of dragonflies gathered along the shoreline at Gifford Pinchot State Park in York County, Pennsylvania. The lake was drained during the winter to perform some maintenance projects and has yet to refill because of the dry spring and early summer we’ve been experiencing. These photos show species seen mostly in the vegetated shallows near the dam.

There are lots of others there too. Do have a look.

Common sense tells us that Brood X Periodical Cicada emergence begins in the southern part of the population zone, where the ground temperatures reach 64° first, then progresses to the north as the weather warms. In the forested hills where the lower Piedmont falls away onto the flat landscape of the Atlantic Coastal Plain in Maryland’s Cecil and Harford Counties, the hum of seventeen-year-old insects saturates a listener’s ears from all directions—the climax nears.

With all that food flying around, you just knew something unusual was going to show up to eat it. It’s a buffet. It’s a smorgasbord. It’s free, it’s all-you-can-eat, and it seems, at least for the moment, like it’s going to last forever. You know it’ll draw a crowd.

The Mississippi Kite (Ictinia mississippiensis), a trim long-winged bird of prey, is a Neotropical migrant, an insect-eating friend of the farmer, and, as the name “kite” suggests, a buoyant flier. It experiences no winter—breeding in the southern United States from April to July, then heading to South America for the remainder of the year. Its diet consists mostly of large flying insects including beetles, leafhoppers, grasshoppers, dragonflies, and, you guessed it, cicadas. Mississippi Kites frequently hunt in groups—usually catching and devouring their food while on the wing. Pairs nest in woodlands, swamps, and in urban areas with ample prey. They are well known for harmlessly swooping at people who happen to get too close to their nest.

Mississippi Kites nest regularly as far north as southernmost Virginia. For at least three decades now, non-breeding second-year birds known as immatures have been noted as wanderers in the Mid-Atlantic States, particularly in late May and early June. They are seen annually at Cape May, New Jersey. They are rare, but usually seen at least once every year, along the Piedmont-Atlantic Coastal Plain border in northern Delaware, northeastern Maryland, and/or southeastern Pennsylvania. Then came the Brood X Periodical Cicadas of 2021.

During the last week of May and these first days of June, there have been dozens of sightings of cicada-eating Mississippi Kites in locations along the lower Piedmont slope in Harford and Cecil Counties in Maryland, at “Bucktoe Creek Preserve” in southern Chester County, Pennsylvania, and in and near Newark in New Castle County, Delaware. They are being seen daily right on the lower Susquehanna watershed’s doorstep.

Today, we journeyed just south of Mason’s and Dixon’s Delaware-Maryland-Pennsylvania triangle to White Clay Creek State Park along Route 896 north of Newark, Delaware. Once there, we took a short bicycle ride into a wooded neighborhood across the street in Maryland to search for the Mississippi Kites that have been reported there in recent days.

Will groups of Mississippi Kites develop a taste for our seventeen-year cicadas and move north into the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed? Ah, to be young and a nomad—that’s the life. Wandering on a whim with one goal in mind—food. It could very well be that now’s the time to be on the lookout for Mississippi Kites, especially where Brood X Periodical Cicadas are abundant.

The emergence of Brood X Periodical Cicadas is now in full swing. If you visit a forested area, you may hear the distant drone of very large concentrations of one or more of the three species that make up the Brood X event. The increasing volume of a chorus tends to attract exponentially greater numbers of male cicadas from within an expanding radius, causing a swarm to grow larger and louder—attracting more and more females to the breeding site.

Each periodical cicada species has a distinctive song. This song concentrates males of the same species at breeding sites—then draws in an abundance of females of the same species to complete the mating process. Large gatherings of periodical cicadas can include all three species, but a close look at swarms on State Game Lands 145 in Lebanon County and State Game Lands 46 (Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area) in Lancaster County during recent days found marked separation by two of the three. Most swarms were dominated by Magicicada septendecim, the largest, most widespread, and most common species. However, nearly mono-specific swarms of M. cassini, the second most numerous species, were found as well. An exceptionally large one was northwest of the village of Colebrook on State Game Lands 145. It was isolated by a tenth of a mile or more from numerous large gatherings of M. septendecim cicadas in the vicinity. These M. cassini cicadas, with a chorus so loud that it outdistanced the songs made by the nearby swarms of M. septendecim, seized the opportunity to separate both audibly and physically from the more dominant species, thus providing better likelihood of maximizing their breeding success.

The process of identifying periodical cicadas is best begun by listening to their choruses, songs, and calls. After all, the sounds of cicadas will lead one to the locations where they are most abundant. The two most common species, M. septendecim and M. cassini, produce a buzzy chorus that, when consisting of hundreds or thousands of cicadas “singing” in unison, creates a droning wail that can carry for a quarter of a mile or more. It’s a surreal humming sound that may remind one of a space ship from a science fiction film.

Listen to the songs of individual cicadas at close range and you’ll hear a difference between the widespread M. septendecim “Pharaoh Periodical Cicada” and the other two species. M. septendecim‘s song is often characterized as a drawn out version of the word “Pharaoh”, hence one of the species’ common names (another is “Seventeen-year Locust”). As part of their courtship ritual, “Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas” sometimes make a purring or cooing sound, which is often extended to sound like kee-ow, then sometimes revved up further to pha-raoh. M. cassini, often known as “Cassin’s Periodical Cicada” or “Dwarf Periodical Cicada”, and the least common species, M. septendecula, often make scratchy clicking or rattling calls as a lead-in to their song. Most observers will find little difficulty locating the widespread M. septendecim “Pharaoh Periodical Cicada” by sound, so listening for something different—the clicking call—is an easy way to zero in on the two less common species.

To penetrate the droning choruses of large numbers of “Pharaoh” and/or “Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas”, sparingly distributed M. septendecula cicadas have a noise-penetrating song consisting of a series of quick raspy notes with a staccato rhythm reminiscent of a pulsating lawn sprinkler. It can often be differentiated by a listener even in the presence of a roaring chorus of one or both of the commoner species. However, a word of caution is due. To call in others of their kind, “Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas” can produce a courtship song similar to that of M. septendecula so that they too can penetrate the choruses of the enormous numbers of “Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas” that concentrate in many areas. To play it safe, it’s best to have a good look at the cicadas you’re trying to identify.

Visually identifying Brood X Periodical Cicadas to the species level is best done by looking for two key field marks—first, the presence or absence of orange between the eye and the root of the wings, and second, the presence or absence of orange bands on the underside of the abdomen. Seeing these field marks clearly requires in-hand examination of the cicada in question.

To reliably separate Brood X Periodical Cicadas by species, it is necessary to get a closeup view of the section of the thorax between the eye and the root (insertion) of the wings, plus a look at the underside of the abdomen. Here’s what you’ll see…

Magicicada septendecim—“Pharaoh Periodical Cicada”

Magicicada cassini—“Cassin’s Periodical Cicada”

Magicicada septendecula

There you have it. Get out and take a closer look at the Brood X Periodical Cicadas near you.

Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia), designated as Pennsylvania’s state flower, is a native evergreen shrub of forests situated on dry rocky slopes with acidic soils. As the common name implies, we think of it mostly as a plant of the mountainous regions—those areas of the Susquehanna watershed north of Harrisburg. It is indeed symbolic of Appalachian forests. But Mountain Laurel can also be found to the south of the capital city in forested highlands of the Piedmont. There, currently, it happens to be in full bloom. Let’s put on a pair of sturdy shoes and take a walk in the Hellam Hills of eastern York County at Rocky Ridge County Park to have a look.

Rain or shine, do get out and have a look at the blooming Mountain Laurel.

The Magi have arrived. Emanating from the shadows of a nearby forest, you may hear the endless drone of what sounds like an extraterrestrial craft. Then you get your first look at those beady red eyes set against a full suit of black armor—out of this world. The Magicicada are here at last.

If you go out and about to observe periodical cicadas, keep an eye open for these species too…