Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

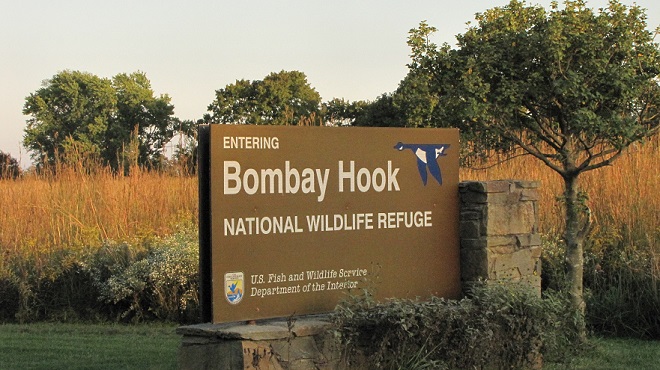

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

The emergence of Brood X Periodical Cicadas is now in full swing. If you visit a forested area, you may hear the distant drone of very large concentrations of one or more of the three species that make up the Brood X event. The increasing volume of a chorus tends to attract exponentially greater numbers of male cicadas from within an expanding radius, causing a swarm to grow larger and louder—attracting more and more females to the breeding site.

Each periodical cicada species has a distinctive song. This song concentrates males of the same species at breeding sites—then draws in an abundance of females of the same species to complete the mating process. Large gatherings of periodical cicadas can include all three species, but a close look at swarms on State Game Lands 145 in Lebanon County and State Game Lands 46 (Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area) in Lancaster County during recent days found marked separation by two of the three. Most swarms were dominated by Magicicada septendecim, the largest, most widespread, and most common species. However, nearly mono-specific swarms of M. cassini, the second most numerous species, were found as well. An exceptionally large one was northwest of the village of Colebrook on State Game Lands 145. It was isolated by a tenth of a mile or more from numerous large gatherings of M. septendecim cicadas in the vicinity. These M. cassini cicadas, with a chorus so loud that it outdistanced the songs made by the nearby swarms of M. septendecim, seized the opportunity to separate both audibly and physically from the more dominant species, thus providing better likelihood of maximizing their breeding success.

The process of identifying periodical cicadas is best begun by listening to their choruses, songs, and calls. After all, the sounds of cicadas will lead one to the locations where they are most abundant. The two most common species, M. septendecim and M. cassini, produce a buzzy chorus that, when consisting of hundreds or thousands of cicadas “singing” in unison, creates a droning wail that can carry for a quarter of a mile or more. It’s a surreal humming sound that may remind one of a space ship from a science fiction film.

Listen to the songs of individual cicadas at close range and you’ll hear a difference between the widespread M. septendecim “Pharaoh Periodical Cicada” and the other two species. M. septendecim‘s song is often characterized as a drawn out version of the word “Pharaoh”, hence one of the species’ common names (another is “Seventeen-year Locust”). As part of their courtship ritual, “Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas” sometimes make a purring or cooing sound, which is often extended to sound like kee-ow, then sometimes revved up further to pha-raoh. M. cassini, often known as “Cassin’s Periodical Cicada” or “Dwarf Periodical Cicada”, and the least common species, M. septendecula, often make scratchy clicking or rattling calls as a lead-in to their song. Most observers will find little difficulty locating the widespread M. septendecim “Pharaoh Periodical Cicada” by sound, so listening for something different—the clicking call—is an easy way to zero in on the two less common species.

To penetrate the droning choruses of large numbers of “Pharaoh” and/or “Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas”, sparingly distributed M. septendecula cicadas have a noise-penetrating song consisting of a series of quick raspy notes with a staccato rhythm reminiscent of a pulsating lawn sprinkler. It can often be differentiated by a listener even in the presence of a roaring chorus of one or both of the commoner species. However, a word of caution is due. To call in others of their kind, “Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas” can produce a courtship song similar to that of M. septendecula so that they too can penetrate the choruses of the enormous numbers of “Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas” that concentrate in many areas. To play it safe, it’s best to have a good look at the cicadas you’re trying to identify.

Visually identifying Brood X Periodical Cicadas to the species level is best done by looking for two key field marks—first, the presence or absence of orange between the eye and the root of the wings, and second, the presence or absence of orange bands on the underside of the abdomen. Seeing these field marks clearly requires in-hand examination of the cicada in question.

To reliably separate Brood X Periodical Cicadas by species, it is necessary to get a closeup view of the section of the thorax between the eye and the root (insertion) of the wings, plus a look at the underside of the abdomen. Here’s what you’ll see…

Magicicada septendecim—“Pharaoh Periodical Cicada”

Magicicada cassini—“Cassin’s Periodical Cicada”

Magicicada septendecula

There you have it. Get out and take a closer look at the Brood X Periodical Cicadas near you.

Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia), designated as Pennsylvania’s state flower, is a native evergreen shrub of forests situated on dry rocky slopes with acidic soils. As the common name implies, we think of it mostly as a plant of the mountainous regions—those areas of the Susquehanna watershed north of Harrisburg. It is indeed symbolic of Appalachian forests. But Mountain Laurel can also be found to the south of the capital city in forested highlands of the Piedmont. There, currently, it happens to be in full bloom. Let’s put on a pair of sturdy shoes and take a walk in the Hellam Hills of eastern York County at Rocky Ridge County Park to have a look.

Rain or shine, do get out and have a look at the blooming Mountain Laurel.

The Magi have arrived. Emanating from the shadows of a nearby forest, you may hear the endless drone of what sounds like an extraterrestrial craft. Then you get your first look at those beady red eyes set against a full suit of black armor—out of this world. The Magicicada are here at last.

If you go out and about to observe periodical cicadas, keep an eye open for these species too…

Let’s take a quiet stroll through the forest to have a look around. The spring awakening is underway and it’s a marvelous thing to behold. You may think it a bit odd, but during this walk we’re not going to spend all of our time gazing up into the trees. Instead, we’re going to investigate the happenings at ground level—life on the forest floor.

There certainly is more to a forest than the living trees. If you’re hiking through a grove of timber getting snared in a maze of prickly Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) and seeing little else but maybe a wild ungulate or two, then you’re in a has-been forest. Logging, firewood collection, fragmentation, and other man-made disturbances inside and near forests take a collective toll on their composition, eventually turning them to mere woodlots. Go enjoy the forests of the lower Susquehanna valley while you still can. And remember to do it gently; we’re losing quality as well as quantity right now—so tread softly.

On a snowy winter day, it sure is nice to see some new visitors at a backyard feeding station. Here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, American Robins have arrived to partake of the offerings.

For this flock of robins, which numbered in excess of 150 individuals, the contents of this tray were a mere garnish to the meal that would sustain them through 72 hours of stormy weather. The main course was the supply of ripe berries on shrubs and trees in the headquarters garden.

Their first choice—the bright red fruits of the Common Winterberry.

After cleaning off the winterberry shrubs, other fruits became part of the three-day-long feast.

Wouldn’t it be great to see these colorful birds in your garden each winter? You can, you know. Won’t you consider adding plantings of native trees and shrubs to your property this spring? Here at the susquehannawildlife.com headquarters we mow no lawn; the lawn is gone. Mixing evergreens and fruit-producing shrubs with native warm-season grasses and flowering plants has created a wildlife oasis absent of that dirty habit of mowing and blowing.

You can find many of the plants seen here at your local garden center. Take a chunk out of your lawn by paying them a visit this spring.

Want a great deal? Many of the County Conservation District offices in the lower Susquehanna region are having their annual spring tree sales right now. Over the years, we obtained many of our evergreens and berry-producing shrubs from these sales for less than two dollars each. At that price you can blanket that stream bank or wet spot in the yard with winterberries and mow it no more! The deadlines for orders are quickly approaching, so act today—literally, act today. Visit your County Conservation District’s website for details including selections, prices, order deadlines, and pickup dates and locations.

County Conservation District Tree Sales

Consult each County Conservation District’s Tree Sale web page for ordering info, pickup locations, and changes to these dates and times.

Cumberland County Conservation District Tree Seedling Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Tuesday, March 30, 2021. Pickup 1 P.M. to 5 P.M., Thursday, April 22, 2021, and 8 A.M. to 2 P.M., Friday, April 23, 2021. https://www.ccpa.net/4636/Tree-Seedling-Sale

Lancaster County Conservation District Tree Sale—deadline for prepaid orders (hand-delivered to drop box) 5 P.M., Friday, March 5, 2021. Pickup 8 A.M. to 5 P.M., Thursday, April 15, 2021. https://www.lancasterconservation.org/tree-sale/

Lebanon County Conservation District Tree Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Thursday, March 11, 2021. Pickup 9 A.M. to 6 P.M., Friday, May 7, 2021. https://www.lccd.org/2021-tree-sale/

Perry County Conservation District Tree Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Wednesday, March 24, 2021. Pickup 10 A.M. to 6 P.M., Thursday, April 8, 2021. www.perrycd.org/Documents/2021 Tree Sale Flyer LEGAL SIZE.pdf

York County Conservation District Seedling Sale—deadline for prepaid orders Monday, March 15, 2021. Pickup 10 A.M. to 6 P.M., Thursday, April 15, 2021. https://www.yorkccd.org/events/2021-seedling-sale

You say you really don’t want to take a look back at 2020? Okay, we understand. But here’s something you may find interesting, and it has to do with the Susquehanna River in 2020.

As you may know, the National Weather Service has calculated the mean temperature for the year 2020 as monitored just upriver from Conewago Falls at Harrisburg International Airport. The 56.7° Fahrenheit value was the highest in nearly 130 years of monitoring at the various stations used to register official climate statistics for the capital city. The previous high, 56.6°, was set in 1998.

Though not a prerequisite for its occurrence, record-breaking heat was accompanied by a drought in 2020. Most of the Susquehanna River drainage basin experienced drought conditions during the second half of the year, particularly areas of the watershed upstream of Conewago Falls. A lack of significant rainfall resulted in low river flows throughout late summer and much of the autumn. Lacking water from the northern reaches, we see mid-river rocks and experience minimal readings on flow gauges along the lower Susquehanna, even if our local precipitation happens to be about average.

Back in October, when the river was about as low as it was going to get, we took a walk across the Susquehanna at Columbia-Wrightsville atop the Route 462/Veteran’s Memorial Bridge to have a look at the benthos—the life on the river’s bottom.

These improvements in water quality and wildlife habitat can have a ripple effect. In 2020, the reduction in nutrient loads entering Chesapeake Bay from the low-flowing Susquehanna may have combined with better-than-average flows from some of the bay’s lesser-polluted smaller tributaries to yield a reduction in the size of the bay’s oxygen-deprived “dead zones”. These dead zones typically occur in late summer when water temperatures are at their warmest, dissolved oxygen levels are at their lowest, and nutrient-fed algal blooms have peaked and died. Algal blooms can self-enhance their severity by clouding water, which blocks sunlight from reaching submerged aquatic plants and stunts their growth—making quantities of unconsumed nutrients available to make more algae. When a huge biomass of algae dies in a susceptible part of the bay, its decay can consume enough of the remaining dissolved oxygen to kill aquatic organisms and create a “dead zone”. The Chesapeake Bay Program reports that the average size of this year’s dead zone was 1.0 cubic miles, just below the 35-year average of 1.2 cubic miles.

Back on a stormy day in mid-November, 2020, we took a look at the tidal freshwater section of Chesapeake Bay, the area known as Susquehanna Flats, located just to the southwest of the river’s mouth at Havre de Grace, Maryland. We wanted to see how the restored American Eelgrass beds there might have fared during a growing season with below average loads of nutrients and life-choking sediments spilling out of the nearby Susquehanna River. Here’s what we saw.

We noticed a few Canvasbacks (Aythya valisineria) on the Susquehanna Flats during our visit. Canvasbacks are renowned as benthic feeders, preferring the tubers and other parts of submerged aquatic plants (a.k.a. submersed aquatic vegetation or S.A.V.) including eelgrass, but also feeding on invertebrates including bivalves. The association between Canvasbacks and eelgrass is reflected in the former’s scientific species name valisineria, a derivitive of the genus name of the latter, Vallisneria.

The plight of the Canvasback and of American Eelgrass on the Susquehanna River was described by Herbert H. Beck in his account of the birds found in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, published in 1924:

“Like all ducks, however, it stops to feed within the county less frequently than formerly, principally because the vast beds of wild celery which existed earlier on broads of the Susquehanna, as at Marietta and Washington Borough, have now been almost entirely wiped out by sedimentation of culm (anthracite coal waste). Prior to 1875 the four or five square miles of quiet water off Marietta were often as abundantly spread with wild fowl as the Susquehanna Flats are now.”

Beck quotes old Marietta resident and gunner Henry Zink:

“Sometimes there were as many as 500,000 ducks of various kinds on the Marietta broad at one time.”

The abundance of Canvasbacks and other ducks on the Susquehanna Flats would eventually plummet too. In the 1950s, there were an estimated 250, 000 Canvasbacks wintering on Chesapeake Bay, primarily in the area of the American Eelgrass, a.k.a. Wild Celery, beds on the Susquehanna Flats. When those eelgrass beds started disappearing during the second half of the twentieth century, the numbers of Canvasbacks wintering on the bay took a nosedive. As a population, the birds moved elsewhere to feed on different sources of food, often in saltier estuarine waters.

Canvasbacks were able to eat other foods and change their winter range to adapt to the loss of habitat on the Susquehanna River and Chesapeake Bay. But not all species are the omnivores that Canvasbacks happen to be, so they can’t just change their diet and/or fly away to a better place. And every time a habitat like the American Eelgrass plant community is eliminated from a region, it fragments the range for each species that relied upon it for all or part of its life cycle. Wildlife species get compacted into smaller and smaller suitable spaces and eventually their abundance and diversity are impacted. We sometimes marvel at large concentrations of birds and other wildlife without seeing the whole picture—that man has compressed them into ever-shrinking pieces of habitat that are but a fraction of the widespread environs they once utilized for survival. Then we sometimes harass and persecute them on the little pieces of refuge that remain. It’s not very nice, is it?

By the end of 2020, things on the Susquehanna were getting back to normal. Near normal rainfall over much of the watershed during the final three months of the year was supplemented by a mid-December snowstorm, then heavy downpours on Christmas Eve melted it all away. Several days later, the Susquehanna River was bank full and dishing out some minor flooding for the first time since early May. Isn’t it great to get back to normal?

SOURCES

Beck, Herbert H. 1924. A Chapter on the Ornithology of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The Lewis Historical Publishing Company. New York, NY.

White, Christopher P. 1989. Chesapeake Bay, Nature of the Estuary: A Field Guide. Tidewater Publishers. Centreville, MD.

Thoughts of October in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed bring to mind scenes of brilliant fall foliage adorning wooded hillsides and stream courses, frosty mornings bringing an end to the growing season, and geese and other birds flying south for the winter.

The autumn migration of birds spans a period equaling nearly half the calendar year. Shorebirds and Neotropical perching birds begin moving through as early as late July, just as daylight hours begin decreasing during the weeks following their peak at summer solstice in late June. During the darkest days of the year, those surrounding winter solstice in late December, the last of the southbound migrants, including some hawks, eagles, waterfowl, and gulls, may still be on the move.

During October, there is a distinct change in the list of species an observer might find migrating through the lower Susquehanna valley. Reduced hours of daylight and plunges in temperatures—particularly frost and freeze events—impact the food sources available to birds. It is during October that we say goodbye to the Neotropical migrants and hello to those more hardy species that spend their winters in temperate climates like ours.

The need for food and cover is critical for the survival of wildlife during the colder months. If you are a property steward, think about providing places for wildlife in the landscape. Mow less. Plant trees, particularly evergreens. Thickets are good—plant or protect fruit-bearing vines and shrubs, and allow herbaceous native plants to flower and produce seed. And if you’re putting out provisions for songbirds, keep the feeders clean. Remember, even small yards and gardens can provide a life-saving oasis for migrating and wintering birds. With a larger parcel of land, you can do even more.

The southbound bird migration of 2020 is well underway. With passage of a cold front coming within the next 48 hours, the days ahead should provide an abundance of viewing opportunities.

Here are some of the species moving through the lower Susquehanna valley right now.

A special message from your local Chinese Mantis (Tenodera sinensis).

Hey you! Yes, you. I pray you’re paying attention to what’s flying around out there, otherwise it’ll all pass you by.

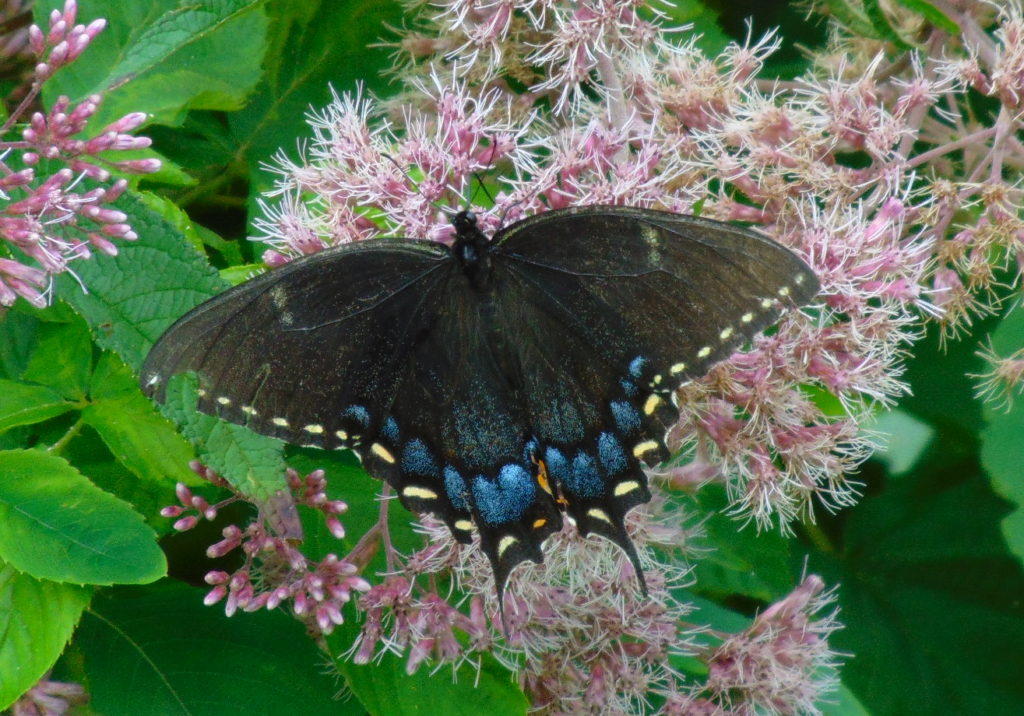

This summer’s hot humid breezes from the south have not only carried swarms of dragonflies into the lower Susquehanna valley, but butterflies too.

So check out these extravagant visitors from south of the Mason-Dixon Line—before my appetite gets the better of me.

There you have it. Get out there and have a look around. These species won’t be active much longer. In just a matter of weeks, our migratory butterflies, including Monarchs, will be heading south and our visiting strays will either follow their lead or risk succumbing to frosty weather.

For more photographs of butterflies, be sure to click the “Butterflies” tab at the top of the page. We’re adding more as we get them.

After nearly a full week of record-breaking cold, including two nights with a widespread freeze, warm weather has returned. Today, for the first time this year, the temperature was above eighty degrees Fahrenheit throughout the lower Susquehanna region. Not only can the growing season now resume, but the northward movement of Neotropical birds can again take flight—much to our delight.

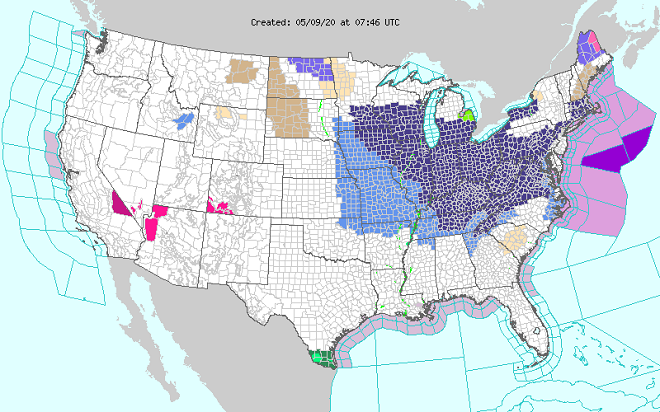

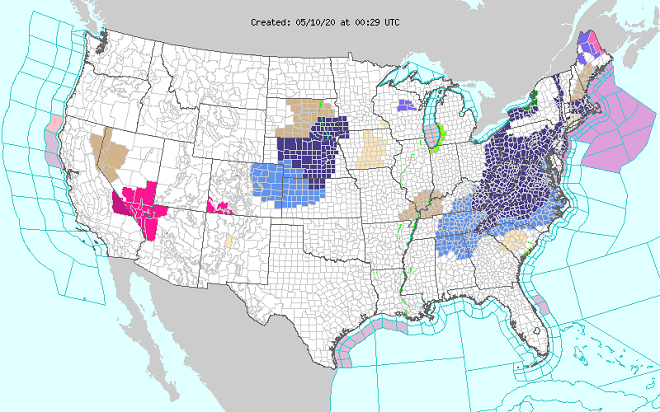

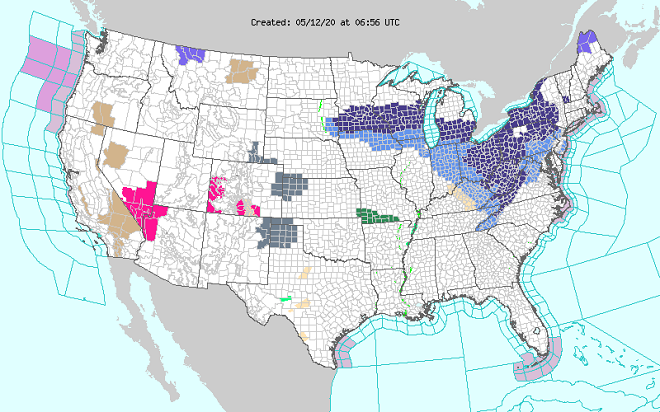

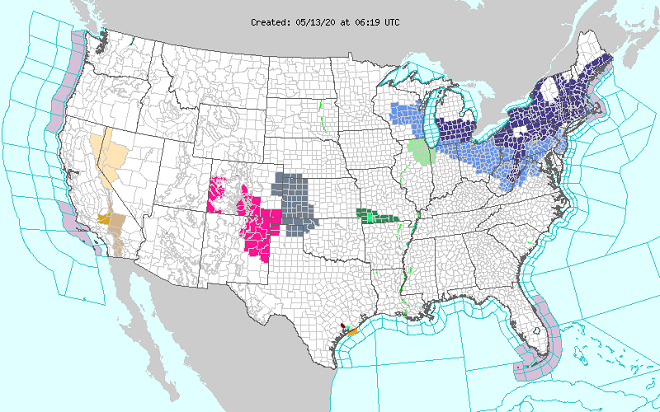

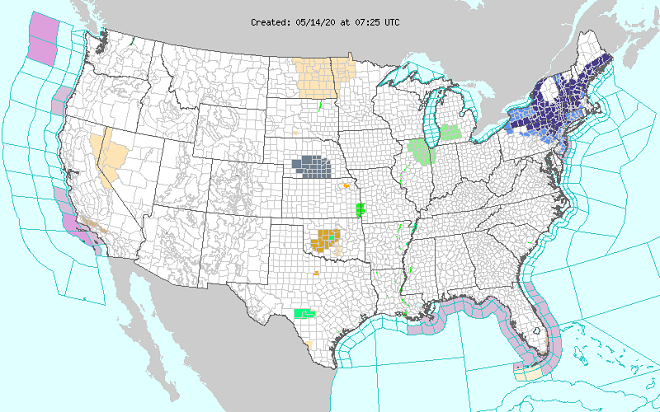

A rainy day on Friday, May 8, preceded the arrival of a cold arctic air mass in the eastern United States. It initiated a sustained layover for many migrating birds.

Freeze warnings were issued for five of the next six mornings. The nocturnal flights of migrating birds, most of them consisting of Neotropical species by now, appeared to be impacted. Even on clear moonlit nights, these birds wisely remained grounded. Unlike the more hardy species that moved north during the preceding weeks, Neotropical birds rely heavily on insects as a food source. For them, burning excessive energy by flying through cold air into areas that may be void of food upon arrival could be a death sentence. So they wait.

Today throughout the lower Susquehanna region, bird songs again fill the air and it seems to be mid-May as we remember it. The flights have resumed.

For those of you who dare to shed that filthy contaminated rag you’ve been told to breathe through so that you might instead get out and enjoy some clean air in a cherished place of solitude, here’s what’s around—go have a look.

The springtime show on the water continues…

Hey, what are those showy flowers?

Wasn’t that refreshing? Now go take a walk.

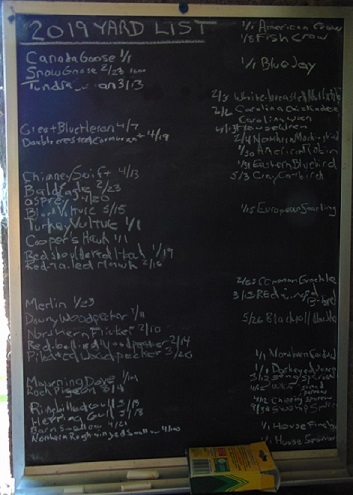

Inside the doorway that leads to your editor’s 3,500 square foot garden hangs a small chalkboard upon which he records the common names of the species of birds that are seen there—or from there—during the year. If he remembers to, he records the date when the species was first seen during that particular year. On New Year’s Day, the results from the freshly ended year are transcribed onto a sheet of notebook paper. On the reverse, the names of butterflies, mammals, and other animals that visited the garden are copied from a second chalkboard that hangs nearby. The piece of paper is then inserted into a folder to join those from previous New Year’s Days. The folder then gets placed back into the editor’s desk drawer beneath a circular saw blade and an old scratched up set of sunglasses—so that he knows exactly where to find it if he wishes to.

A quick glance at this year’s list calls to mind a few recollections.

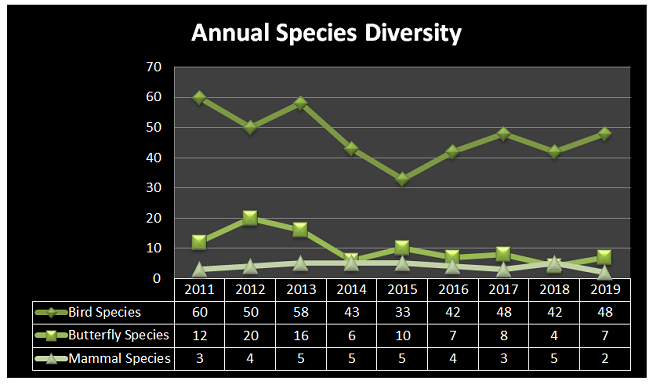

Before putting the folder back into the drawer for another year, the editor decided to count up the species totals on each of the sheets and load them into the chart maker in the computer.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

It appears that, at the very least, the garden habitat has been disconnected from the home ranges of many species by fragmentation. His little oasis is now isolated in a landscape that becomes increasingly hostile to native wildlife with each passing year. The paving of more parking areas, the elimination of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous growth from the large number of rental properties in the area, the alteration of the biology of the nearby stream by hand-fed domestic ducks, light pollution, and the outdoor use of pesticides have all contributed to the separation of the editor’s tiny sanctuary from the travel lanes and core habitats of many of the species that formerly visited, fed, or bred there. In 2019, migrants, particularly “fly-overs”, were nearly the only sightings aside from several woodpeckers, invasive House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and hardy Mourning Doves. Even rascally European Starlings became sporadic in occurrence—imagine that! It was the most lackluster year in memory.

If habitat fragmentation were the sole cause for the downward trend in numbers and species, it would be disappointing, but comprehensible. There would be no cause for greater alarm. It would be a matter of cause and effect. But the problem is more widespread.

Although the editor spent a great deal of time in the garden this year, he was also out and about, traveling hundreds of miles per week through lands on both the east and the west shores of the lower Susquehanna. And on each journey, the number of birds seen could be counted on fingers and toes. A decade earlier, there were thousands of birds in these same locations, particularly during the late summer.

In the lower Susquehanna valley, something has drastically reduced the population of birds during breeding season, post-breeding dispersal, and the staging period preceding autumn migration. In much of the region, their late-spring through summer absence was, in 2019, conspicuous. What happened to the tens of thousands of swallows that used to gather on wires along rural roads in August and September before moving south? The groups of dozens of Eastern Kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus) that did their fly-catching from perches in willows alongside meadows and shorelines—where are they?

Several studies published during the autumn of 2019 have documented and/or predicted losses in bird populations in the eastern half of the United States and elsewhere. These studies looked at data samples collected during recent decades to either arrive at conclusions or project future trends. They cite climate change, the feline infestation, and habitat loss/degradation among the factors contributing to alterations in range, migration, and overall numbers.

There’s not much need for analysis to determine if bird numbers have plummeted in certain Lower Susquehanna Watershed habitats during the aforementioned seasons—the birds are gone. None of these studies documented or forecast such an abrupt decline. Is there a mysterious cause for the loss of the valley’s birds? Did they die off? Is there a disease or chemical killing them or inhibiting their reproduction? Is it global warming? Is it Three Mile Island? Is it plastic straws, wind turbines, or vehicle traffic?

The answer might not be so cryptic. It might be right before our eyes. And we’ll explore it during 2020.

In the meantime, Uncle Ty and I going to the Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg. You should go too. They have lots of food there.

With autumn coming to a close, let’s have a look at some of the fascinating insects (and a spider) that put on a show during some mild afternoons in the late months of 2019.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

It’s sprayed with herbicides. It’s mowed and mangled. It’s ground to shreds with noisy weed-trimmers. It’s scorned and maligned. It’s been targeted for elimination by some governments because it’s undesirable and “noxious”. And it has that four letter word in its name which dooms the fate of any plant that possesses it. It’s the Common Milkweed, and it’s the center of activity in our garden at this time of year. Yep, we said milk-WEED.

Now, you need to understand that our garden is small—less than 2,500 square feet. There is no lawn, and there will be no lawn. We’ll have nothing to do with the lawn nonsense. Those of you who know us, know that the lawn, or anything that looks like lawn, are through.

Anyway, most of the plants in the garden are native species. There are trees, numerous shrubs, some water features with aquatic plants, and filling the sunny margins is a mix of native grassland plants including Common Milkweed. The unusually wet growing season in 2018 has been very kind to these plants. They are still very green and lush. And the animals that rely on them are having a banner year. Have a look…

We’ve planted a variety of native grassland species to help support the milkweed structurally and to provide a more complete habitat for Monarch butterflies and other native insects. This year, these plants are exceptionally colorful for late-August due to the abundance of rain. The warm season grasses shown below are the four primary species found in the American tall-grass prairies and elsewhere.

There was Monarch activity in the garden today like we’ve never seen before—and it revolved around milkweed and the companion plants.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

At the moment there is a heavy snow falling, not an unusual occurrence for mid-February, nevertheless, it is a change in weather. Forty-eight hours ago we were in the midst of a steady rain and temperatures were in the sixties. The snow and ice had melted away and a touch of spring was in the air.

Anyone casually looking about while outdoors during these last several days may have noticed that birds are indeed beginning to migrate north in the lower Susquehanna valley. Killdeer, American Robins, Eastern Bluebirds, Red-winged Blackbirds, and Common Grackles are easily seen or heard in most of the area now.

Just hours ago, between nine o’clock this morning and one o’clock this afternoon, there was a spectacular flight of birds following the river north, their spring migration well underway. In the blue skies above Conewago Falls, a steady parade of Ring-billed Gulls was utilizing thermals and riding a tailwind from the south-southeast to cruise high overhead on a course toward their breeding range.

The swirling hoards of Ring-billed Gulls attracted other migrants to take advantage of the thermals and glide paths on the breeze. Right among them were 44 American Herring Gulls, 3 Great Black-backed Gulls, 12 Tundra Swans (Cygnus columbianus), 10 Canada Geese, 3 Northern Pintails (Anas acuta), 6 Common Mergansers, 3 Red-tailed Hawks, a Red-shouldered Hawk, 6 Bald Eagles (non-adults), 8 Black Vultures, and 5 Turkey Vultures.

In the afternoon, the clouds closed in quickly, the flight ended, and by dusk more than an inch of snow was on the ground. Looks like spring to me.

A very light fog lifted quickly at sunrise. Afterward, there was a minor movement of migrants: forty-nine Ring-billed Gulls, a few American Herring Gulls, a Red-shouldered Hawk following the river to the southeast, and small flocks totaling nine Cedar Waxwings and twenty-eight Red-winged Blackbirds.

In the Riparian Woodland, small mixed flocks of winter resident and year-round resident birds were actively feeding. They must build and maintain a layer of body fat to survive blustery cold nights and the possible lack of access to food during snowstorms. There’s no time to waste; nasty weather could bring fatal hardship to these birds soon.

They get a touch of it here, and a sparkle or two there. Maybe, for a couple of hours each day, the glorious life-giving glow of the sun finds an opening in the canopy to warm and nourish their leaves, then the rays of light creep away across the forest floor, and it’s shade for the remainder of the day.

The flowering plants which thrive in the understory of the Riparian Woodlands often escape much notice. They gather only a fraction of the daylight collected by species growing in full exposure to the sun. Yet, by season’s end, many produce showy flowers or nourishing fruits of great import to wildlife. While light may be sparingly rationed through the leaves of the tall trees overhead, moisture is nearly always assured in the damp soils of the riverside forest. For these plants, growth is slow, but continuous. And now, it’s show time.

So let’s take a late-summer stroll through the Riparian Woodlands of Conewago Falls, minus the face full of cobwebs, and have a look at some of the strikingly beautiful plants found living in the shadows.

SOURCES

Long, David; Ballentine, Noel H.; and Marks, James G., Jr. 1997. Treatment of Poison Ivy/Oak Allergic Contact Dermatitis With an Extract of Jewelweed. American Journal of Contact Dermatitis. 8(3): pp. 150-153.

Newcomb, Lawrence. 1977. Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide. Little, Brown and Company. Boston, Massachusetts.

A couple of inches of rain this week caused a small increase in the flow of the river, just a burp, nothing major. This higher water coincided with some breezy days that kicked up some chop on the open waters of the Susquehanna upstream of Conewago Falls. Apparently it was just enough turbulence to uproot some aquatic plants and send them floating into the falls.

Piled against and upon the upstream side of many of the Pothole Rocks were thousands of two to three feet-long flat ribbon-like opaque green leaves of Tapegrass, also called Wild Celery, but better known as American Eelgrass (Vallisneria americana). Some leaves were still attached to a short set of clustered roots. It appears that most of the plants broke free from creeping rootstock along the edge of one of this species’ spreading masses which happened to thrive during the second half of the summer. You’ll recall that persistent high water through much of the growing season kept aquatic plants beneath a blanket of muddy current. The American Eelgrass colonies from which these specimens originated must have grown vigorously during the favorable conditions in the month of August. A few plants bore the long thread-like pistillate flower stems with a fruit cluster still intact. During the recent few weeks, there have been mats of American Eelgrass visible, the tops of their leaves floating on the shallow river surface, near the east and west shorelines of the Susquehanna where it begins its pass through the Gettysburg Basin near the Pennsylvania Turnpike bridge at Highspire. This location is a probable source of the plants found in the falls today.

The cool breeze from the north was a perfect fit for today’s migration count. Nocturnal migrants settling down for the day in the Riparian Woodlands at sunrise included more than a dozen warblers and some Gray Catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis). Diurnal migration was underway shortly thereafter.

Four Bald Eagles were counted as migrants this morning. Based on plumage, two were first-year eagles (Juvenile) seen up high and flying the river downstream, one was a second-year bird (Basic I) with a jagged-looking wing molt, and a third was probably a fourth year (Basic III) eagle looking much like an adult with the exception of a black terminal band on the tail. These birds were the only ones which could safely be differentiated from the seven or more Bald Eagles of varying ages found within the past few weeks to be lingering at Conewago Falls. There were as many as a dozen eagles which appeared to be moving through the falls area that may have been migrating, but the four counted were the only ones readily separable from the locals.

Red-tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) were observed riding the wind to journey not on a course following the river, but flying across it and riding the updraft on the York Haven Diabase ridge from northeast to southwest.

Bank Swallows (Riparia riparia) seem to have moved on. None were discovered among the swarms of other species today.

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Caspian Terns, Cedar Waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum), and Chimney Swifts (Chaetura pelagica) were migrating today, as were Monarch butterflies.

Not migrating, but always fun to have around, all four wise guys were here today. I’m referring to the four members of the Corvid family regularly found in the Mid-Atlantic states: Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata), American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), Fish Crow (Corvus ossifragus), and Common Raven (Corvus corax).

SOURCES

Klots, Elsie B. 1966. The New Field Book of Freshwater Life. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, NY.

It’s tough being good-looking and liked by so many. You’ve got to watch out, because popularity makes you a target. Others get jealous and begin a crusade to have you neutralized and removed from the spotlight. They’ll start digging to find your little weaknesses and flaws, then they’ll exploit them to destroy your reputation. Next thing you know, people look at you as some kind of hideous scoundrel.

Today, bright afternoon sunshine and a profusion of blooming wildflowers coaxed butterflies into action. It was one of those days when you don’t know where to look first.

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) has a bad reputation. Not native to the Americas, this prolific seed producer began spreading aggressively into many wetlands following its introduction. It crowds out native plant species and can have a detrimental impact on other aquatic life. Stands of loosestrife in slow-moving waters can alter flows, trap sediment, and adversely modify the morphology of waterways. Expensive removal and biological control are often needed to protect critical habitat.

The dastardly Purple Loosestrife may have only two positive attributes. First, it’s a beautiful plant. And second, it’s popular; butterflies and other pollinators find it to be irresistible and go wild over the nectar.

Don’t you just adore the wonderful butterflies. Everybody does. Just don’t tell anyone that they’re pollinating those dirty filthy no-good Purple Loosestrife plants.

SOURCES

Brock, Jim P., and Kenn Kaufman. 2003. Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

Newcomb, Lawrence. 1977. Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide. Little, Brown and Company. Boston, Massachusetts.

There’s something frightening going on down there. In the sand, beneath the plants on the shoreline, there’s a pile of soil next to a hole it’s been digging. Now, it’s dragging something toward the tunnel it made. What does it have? Is that alive?

We know how the system works, the food chain that is. The small stuff is eaten by the progressively bigger things, and there are fewer of the latter than there are of the former, thus the whole network keeps operating long-term. Some things chew plants, others devour animals whole or in part, and then there are those, like us, that do both. In the natural ecosystem, predators keep the numerous little critters from getting out of control and decimating certain other plant or animal populations and wrecking the whole business. When man brings an invasive and potentially destructive species to a new area, occasionally we’re fortunate enough to have a native species adapt and begin to keep the invader under control by eating it. It maintains the balance. It’s easy enough to understand.

Late summer days are marked by a change in the sounds coming from the forests surrounding the falls. For birds, breeding season is ending, so the males cease their chorus of songs and insects take over the musical duties. The buzzing calls of male “annual cicadas” (Neotibicen species) are the most familiar. The female “annual cicada” lays her eggs in the twigs of trees. After hatching, the nymphs drop to the ground and burrow into the soil to live and feed along tree roots for the next two to five years. A dry exoskeleton clinging to a tree trunk is evidence that a nymph has emerged from its subterranean haunts and flown away as an adult to breed and soon thereafter die. Flights of adult “annual cicadas” occur every year, but never come anywhere close to reaching the enormous numbers of “periodical cicadas” (Magicicada species). The three species of “periodical cicadas” synchronize their life cycles throughout their combined regional populations to create broods that emerge as spectacular flights once every 13 or 17 years.

For the adult cicada, there is danger, and that danger resembles an enormous bee. It’s an Eastern Cicada Killer (Specius speciosus) wasp, and it will latch onto a cicada and begin stinging while both are in flight. The stings soon paralyze the screeching, panicked cicada. The Cicada Killer then begins the task of airlifting and/or dragging its victim to the lair it has prepared. The cicada is placed in one of more than a dozen cells in the tunnel complex where it will serve as food for the wasp’s larvae. The wasp lays an egg on the cicada, then leaves and pushes the hole closed. The egg hatches in a several days and the larval grub is on its own to feast upon the hapless cicada.

Other species in the Solitary Wasp family (Sphecidae) have similar life cycles using specific prey which they incapacitate to serve as sustenance for their larvae.

The Solitary Wasps are an important control on the populations of their respective prey. Additionally, the wasp’s bizarre life cycle ensures a greater survival rate for its own offspring by providing sufficient food for each of its progeny before the egg beginning its life is ever put in place. It’s complete family planning.

The cicadas reproduce quickly and, as a species, seem to endure the assault by Cicada Killers, birds, and other predators. The periodical cicadas (Magicicada), with adult flights occurring as a massive swarm of an entire population every thirteen or seventeen years, survive as species by providing predators with so ample a supply of food that most of the adults go unmolested to complete reproduction. Stay tuned, 2021 is due to be the next periodical cicada year in the vicinity of Conewago Falls.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

The tall seed-topped stems swaying in a summer breeze are a pleasant scene. And the colorful autumn shades of blue, orange, purple, red, and, of course, green leaves on these clumping plants are nice. But of the multitude of flowering plants, Big Bluestem, Freshwater Cordgrass, and Switchgrass aren’t much of a draw. No self-respecting bloom addict is going out of their way to have a gander at any grass that hasn’t been subjugated and tamed by a hideous set of spinning steel blades. Grass flowers…are you kidding?

O.K., so you need something more. Here’s more.

Meet the Partridge Pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata). It’s an annual plant growing in the Riverine Grasslands at Conewago Falls as a companion to Big Bluestem. It has a special niche growing in the sandy and, in summertime, dry soils left behind by earlier flooding and ice scour. The divided leaves close upon contact and also at nightfall. Bees and other pollinators are drawn to the abundance of butter-yellow blossoms. Like the familiar pea of the vegetable garden, the flowers are followed by flat seed pods.

But wait, here’s more.

In addition to its abundance in Conewago Falls, the Halberd-leaved Rose Mallow (Hibiscus laevis) is the ubiquitous water’s edge plant along the free-flowing Susquehanna River for miles downstream. It grows in large clumps, often defining the border between the emergent zone and shore-rooted plants. It is particularly successful in accumulations of alluvium interspersed with heavier pebbles and stone into which the roots will anchor to endure flooding and scour. Such substrate buildup around the falls, along mid-river islands, and along the shores of the low-lying Riparian Woodlands immediately below the falls are often quite hospitable to the species.

A second native wildflower species in the genus Hibiscus is found in the Conewago Falls floodplain, this one in wetlands. The Swamp Rose Mallow (H. moscheutos) is similar to Halberd-leaved Rose Mallow, but sports more variable and colorful blooms. The leaves are toothed without the deep halberd-style lobes and, like the stems, are downy. As the common name implies, it requires swampy habitat with ample water and sunlight.

In summary, we find Partridge Pea in the Riverine Grasslands growing in sandy deposits left by flood and ice scour. We find Halberd-leaved Rose Mallow rooted at the border between shore and the emergent zone. We find Swamp Rose Mallow as an emergent in the wetlands of the floodplain. And finally, we find marshmallows in only one location in the area of Conewago Falls. Bon ap’.

SOURCES

Newcomb, Lawrence. 1977. Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide. Little, Brown and Company. Boston, Massachusetts.

It has not been a good summer if you happen to be a submerged plant species in the lower Susquehanna River. Regularly occurring showers and thunderstorms have produced torrents of rain and higher than usual river stages. The high water alone wouldn’t prevent you from growing, colonizing a wider area, and floating several small flowers on the surface, however, the turbidity, the suspended sediment, would. The muddy current casts a dirty shadow on the benthic zone preventing bottom-rooted plants from getting much headway. There will be smaller floating mats of the uppermost leaves of these species. Fish and invertebrates which rely upon this habitat for food and shelter will find sparse accommodation…better luck next year.

Due to the dirty water, fish-eating birds are having a challenging season as they try to catch sufficient quantities of prey to feed themselves and their offspring. A family of Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) at Conewago Falls, including recently fledged young, were observed throughout this morning and had no successful catches. Of the hundred or more individual piscivores of various species present, none were seen retrieving fish from the river. The visibility in the water column needs to improve before fishing is a viable enterprise again.

While the submerged plant communities may be stunted by 2017’s extraordinary water levels, there is a very unique habitat in Conewago Falls which endures summer flooding and, in addition, requires the scouring effects of river ice to maintain its mosaic of unique plants. It is known as a Riverine Grassland or scour grassland.

The predominant plants of the Riverine Grasslands are perennial warm-season grasses. The deep root systems of these hardy species have evolved to survive events which prevent the grassland from reverting to woodland through succession. Fire, intense grazing by wild herd animals, poor soils, drought, and other hardships, including flooding and ice scour, will eliminate intolerant plant species and prevent an area from reforesting. In winter and early spring, scraping and grinding by flood-driven chunk ice mechanically removes large woody and poorly rooted herbaceous growth from susceptible portions of the falls. These adverse conditions clear the way for populations of species more often associated with North America’s tall grass prairies to take root. Let’s have a look at some of the common species found in the “Conewago Falls Pothole Rocks Prairie”.

The Conewago Falls Riverine Grassland is home to numerous other very interesting plants. We’ll look at more of them next time.

SOURCES

Brown, Lauren. 1979. Grasses, An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

She ate only toaster pastries…that’s it…nothing else. Every now and then, on special occasions, when a big dinner was served, she’d have a small helping of mashed potatoes, no gravy, just plain, thank you. She received all her nutrition from several meals a week of macaroni and cheese assembled from processed ingredients found in a cardboard box. It contains eight essential vitamins and minerals, don’t you know? You remember her, don’t you?

Adult female butterflies must lay their eggs where the hatched larvae will promptly find the precise food needed to fuel their growth. These caterpillars are fussy eaters, with some able to feed upon only one particular species or genus of plant to grow through the five stages, the instars, of larval life. The energy for their fifth molt into a pupa, known as a chrysalis, and metamorphosis into an adult butterfly requires mass consumption of the required plant matter. Their life cycle causes most butterflies to be very habitat specific. These splendid insects may visit the urban or suburban garden as adults to feed on nectar plants, however, successful reproduction relies upon environs which include suitable, thriving, pesticide-free host plants for the caterpillars. Their survival depends upon more than the vegetation surrounding the typical lawn will provide.

The Monarch (Danaus plexippus), a butterfly familiar in North America for its conspicuous autumn migrations to forests in Mexico, uses the milkweeds (Asclepias) almost exclusively as a host plant. Here at Conewago Falls, wetlands with Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and unsprayed clearings with Common Milkweed (A. syriaca) are essential to the successful reproduction of the species. Human disturbance, including liberal use of herbicides, and invasive plant species can diminish the biomass of the Monarch’s favored nourishment, thus reducing significantly the abundance of the migratory late-season generation.

Butterflies are good indicators of the ecological health of a given environment. A diversity of butterfly species in a given area requires a wide array of mostly indigenous plants to provide food for reproduction. Let’s have a look at some of the species seen around Conewago Falls this week…

The spectacularly colorful butterflies are a real treat on a hot summer day. Their affinity for showy plants doubles the pleasure.

By the way, I’m certain by now you’ve recalled that fussy eater…and how beautiful she grew up to be.

SOURCES

Brock, Jim P., and Kaufman, Kenn. 2003. Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.