LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

Beginning this evening at about 10:44 PM EDT, and lasting until almost 11 o’clock, the gaseous clouds from two of three TOMEX+ (Turbulent Oxygen Mixing Experiment) sounding rockets launched from NASA’s Wallops Island Flight Facility near Chincoteague, Virginia, were visible in the southern skies of much of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. From susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, we were able to see and photograph the glowing clouds created by these vapor releases. Within minutes, the contrail-like wisps were swept away by the swift thin air of the mesosphere, the area lying just below the thermosphere and the Kármán Line—the border of outer space 100 kilometers (62 miles) above sea level. According to NASA, “This mission aims to provide the clearest 3D view yet of turbulence in the region at the edge of space.”

The deluge of rain that soaked the lower Susquehanna watershed during last week is now just a memory. Streams to the west of the river, where the flooding courtesy of the remnants of Hurricane Debby was most severe, have reached their crest and receded. Sliding away toward the Chesapeake and Atlantic is all that runoff, laden with a brew of pollutants including but not limited to: agricultural nutrients, sediment, petroleum products, sewage, lawn chemicals, tires, dog poop, and all that litter—paper, plastics, glass, Styrofoam, and more. For aquatic organisms including our freshwater fish, these floods, particularly when they occur in summer, can compound the effects of the numerous stressors that already limit their ability to live, thrive, and reproduce.

One of those preexisting stressors, high water temperature, can be either intensified or relieved by summertime precipitation. Runoff from forested or other densely vegetated ground normally has little impact on stream temperature. But segments of waterways receiving significant volumes of runoff from areas of sun-exposed impervious ground will usually see increases during at least the early stages of a rain event. Fortunately, projects implemented to address the negative impacts of stormwater flow and stream impairment can often have the additional benefit of helping to attenuate sudden rises in stream temperature.

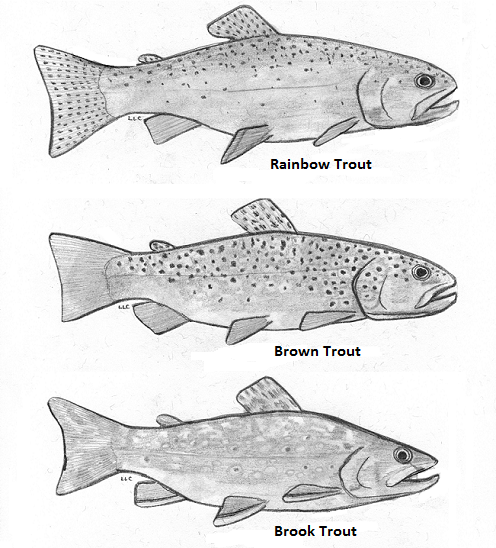

Of the fishes inhabiting the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s temperate streams, the least tolerant of summer warming are the trouts and sculpins—species often described as “coldwater fishes”. Coldwater fishes require water temperatures below 70° Fahrenheit to thrive and reproduce. The optimal temperature range is 50° to 65° F. In the lower Susquehanna valley, few streams are able to sustain trouts and sculpins through the summer months—largely due to the effects of warm stormwater runoff and other forms of impairment.

Coldwater fishes are generally found in small spring-fed creeks and headwaters runs. Where stream gradient, substrate, dissolved oxygen, and other parameters are favorable, some species may be tolerant of water warmer than the optimal values. In other words, these temperature classifications are not set in stone and nobody ever explained ichthyology to a fish, so there are exceptions. The Brown Trout for example is sometimes listed as a “coldwater transition fish”, able to survive and reproduce in waters where stream quality is exceptionally good but the temperature may periodically reach the mid-seventies.

More tolerant of summer heat than the trouts, sculpins, and daces are the “coolwater fishes”—species able to feed, grow, and reproduce in streams with a temperature of less than 80° F, but higher than 60° F. Coolwater fishes thrive in creeks and rivers that hover in the 65° to 70° F range during summer.

What are the causes of modern-day reductions in coldwater and coolwater fish habitats in the lower Susquehanna River and its hundreds of miles of tributaries? To answer that, let’s take a look at the atmospheric, cosmic, and hydrologic processes that impact water temperature. Technically, these processes could be measured as heat flux—the rate of heat energy transfer per unit area per unit time, frequently expressed as watts per meter squared (W/m²). Without getting too technical, we’ll just take a look at the practical impact these processes have on stream temperatures.

HEAT FLUX PROCESSES IN A SEGMENT OF STREAM

Now that we have a basic understanding of the heat flux processes responsible for determining the water temperatures of our creeks and rivers, let’s venture a look at a few graphics from gauge stations on some of the lower Susquehanna’s tributaries equipped with appropriate United States Geological Survey monitoring devices. While the data from each of these stations is clearly noted to be provisional, it can still be used to generate comparative graphics showing basic trends in easy-to-monitor parameters like temperature and stream flow.

Each image is self-labeled and plots stream temperature in degrees Fahrenheit (bold blue) and stream discharge in cubic feet per second (thin blue).

The daily oscillations in temperature reflect the influence of several heat flux processes. During the day, solar (shortwave) radiation and convection from summer air, especially those hot south winds, are largely responsible for the daily rises of about 5° F. Longwave radiation has a round-the-clock influence—adding heat to the stream during the day and mostly shedding it at night. Atmospheric exchange including evaporative cooling may help moderate the rise in stream temperatures during the day, and certainly plays a role in bringing them back down after sunset. Along its course this summer, the West Conewago Creek absorbed enough heat to render it a warmwater fishery in the area of the gauging station. The West Conewago is a shallow, low gradient stream over almost its entire course. Its waters move very slowly, thus extending their exposure time to radiated heat flux and reducing the benefit of cooling by atmospheric exchange. Fortunately for bass, catfish, and sunfish, these temperatures are in the ideal range for warmwater fishes to feed, grow, and reproduce—generally over 80° F, and ideally in the 70° to 85° F range. Coolwater fishes though, would not find this stream segment favorable. It was consistently above the 80° F maximum and the 60° to 70° F range preferred by these species. And coldwater fishes, well, they wouldn’t be caught dead in this stream segment. Wait, scratch that—the only way they would be caught in this segment is dead. No trouts or sculpins here.

Look closely and you’ll notice that although the temperature pattern on this chart closely resembles that of the West Conewago’s, the readings average about 5 degrees cooler. This may seem surprising when one realizes that the Codorus follows a channelized path through the heart of York City and its urbanized suburbs—a heat island of significance to a stream this size. Before that it passes through numerous impoundments where its waters are exposed to the full energy of the sun. The tempering factor for the Codorus is its baseflow. Despite draining a smaller watershed than its neighbor to the north, the Codorus’s baseflow (low flow between periods of rain) was 96 cubic feet per second on August 5th, nearly twice that of the West Conewago (51.1 cubic feet per second on August 5th). Thus, the incoming heat energy was distributed over a greater mass in the Codorus and had a reduced impact on its temperature. Though the Codorus is certainly a warmwater fishery in its lower reaches, coolwater and transitional fishes could probably inhabit its tributaries in segments located closer to groundwater sources without stress. Several streams in its upper reaches are in fact classified as trout-stocked fisheries.

The Kreutz Creek gauge shows temperature patterns similar to those in the West Conewago and Codorus data sets, but notice the lower overall temperature trend and the flow. Kreutz Creek is a much smaller stream than the other two, with a flow averaging less than one tenth that of the West Conewago and about one twentieth of that in the Codorus. And most of the watershed is cropland or urban/suburban space. Yet, the stream remains below 80° F through most of the summer. The saving graces in Kreutz Creek are reduced exposure time and gradient. The waters of Kreutz Creek tumble their way through a small watershed to enter the Susquehanna within twenty-four hours, barely time to go through a single daily heating and cooling cycle. As a result, their is no chance for water to accumulate radiant and convective heat over multiple summer days. The daily oscillations in temperature are less amplified than we find in the previous streams—a swing of about three degrees compared to five. This indicates a better balance between heat flux processes that raise temperature and those that reduce it. Atmospheric exchange in the stream’s riffles, forest cover, and good hyporheic exchange along its course could all be tempering factors in Kreutz Creek. From a temperature perspective, Kreutz Creek provides suitable waters for coolwater fishes.

Muddy Creek is a trout-stocked fishery, but it cannot sustain coldwater species through the summer heat. Though temperatures in Muddy Creek may be suitable for coolwater fishes, silt, nutrients, low dissolved oxygen, and other factors could easily render it strictly a warmwater fishery, inhabited by species tolerant of significant stream impairment.

A significant number of stream segments in the Chiques watershed have been rehabilitated to eliminate intrusion by grazing livestock, cropland runoff, and other sources of impairment. Through partnerships between a local group of watershed volunteers and landowners, one tributary, Donegal Creek, has seen riparian buffers, exclusion fencing, and other water quality and habitat improvements installed along nearly ever inch of its run from Donegal Springs through high-intensity farmland to its mouth on the main stem of the Chiques just above its confluence with the Susquehanna. The improved water quality parameters in the Donegal support native coldwater sculpins and an introduced population of reproducing Brown Trout. While coldwater habitat is limited to the Donegal, the main stem of the Chiques and its largest tributary, the Little Chiques Creek, both provide suitable temperatures for coolwater fishes.

Despite its meander through and receipt of water from high-intensity farmland, the temperature of the lower Conewago (East) maxes out at about 85° F, making it ideal for warmwater fishes and even those species that are often considered coolwater transition fishes like introduced Smallmouth Bass, Rock Bass, Walleye, and native Margined Madtom. This survivable temperature is a testament to the naturally occurring and planted forest buffers along much of the stream’s course, particularly on its main stem. But the Conewago suffers serious baseflow problems compared to other streams we’ve looked at so far. Just prior to the early August storms, flow was well below 10 cubic feet per second for a drainage area of more than fifty square miles. While some of this reduced flow is the result of evaporation, much of it is anthropogenic in origin as the rate of groundwater removal continues to increase and a recent surge in stream withdraws for irrigation reaches its peak during the hottest days of summer.

A little side note—the flow rate on the Conewago at the Falmouth gauge climbed to about 160 cubic feet per second as a result of the remnants of Hurricane Debby while the gauge on the West Conewago at Manchester skyrocketed to about 20,000 cubic feet per second. Although the West Conewago’s watershed (drainage area) is larger than that of the Conewago on the east shore, it’s larger only by a multiple of two or three, not 125. That’s a dramatic difference in rainfall!

The temperatures at the Bellaire monitoring station, which is located upstream of the Conewago’s halfway point between its headwaters in Mount Gretna and its mouth, are quite comparable to those at the Falmouth gauge. Although a comparison between these two sets of data indicate a low net increase in heat absorption along the stream’s course between the two points, it also suggests sources of significant warming upstream in the areas between the Bellaire gauge and the headwaters.

The waters of the Little Conewago are protected within planted riparian buffers and mature woodland along much of their course to the confluence with the Conewago’s main stem just upstream of Bellaire. This tributary certainly isn’t responsible for raising the temperature of the creek, but is instead probably helping to cool it with what little flow it has.

Though mostly passing through natural and planted forest buffers above its confluence with the Little Conewago, the main stem’s critically low baseflow makes it particularly susceptible to heat flux processes that raise stream temperatures in segments within the two or three large agricultural properties where owners have opted not to participate in partnerships to rehabilitate the waterway. The headwaters area, while largely within Pennsylvania State Game Lands, is interspersed with growing residential communities where potable water is sourced from hundreds of private and community wells—every one of them removing groundwater and contributing to the diminishing baseflow of the creek. Some of that water is discharged into the stream after treatment at the two municipal sewer plants in the upper Conewago. This effluent can become quite warm during processing and may have significant thermal impact when the stream is at a reduced rate of flow. A sizeable headwaters lake is seasonally flooded for recreation in Mount Gretna. Such lakes can function as effective mid-day collectors of solar (shortwave) radiation that both warms the water and expedites atmospheric exchange.

Though Conewago Creek (East) is classified as a trout-stocked fishery in its upper reaches in Lebanon County, its low baseflow and susceptibility to warming render it inhospitable to these coldwater fishes by late-spring/early summer.

The removal of two water supply dams on the headwaters of Hammer Creek at Rexmont eliminated a large source of temperature fluctuation on the waterway, but did little to address the stream’s exposure to radiant and convective heat flux processes as it meanders largely unprotected out of the forest cover of Pennsylvania State Game Lands and through high-intensity farmlands in the Lebanon Valley. Moderating the temperature to a large degree is the influx of karst water from Buffalo Springs, located about two miles upstream from this gauging station, and other limestone springs that feed tributaries which enter the Hammer from the east and north. Despite the cold water, the impact of the stream’s nearly total exposure to radiative and other warming heat flux processes can readily be seen in the graphic. Though still a coldwater fishery by temperature standards, it is rather obvious that rapid heating and other forms of impairment await these waters as they continue flowing through segments with few best management practices in place for mitigating pollutants. By the time Hammer Creek passes back through the Furnace Hills and Pennsylvania State Game Lands, it is leaning toward classification as a coolwater fishery with significant accumulations of sediment and nutrients. But this creek has a lot going for it—mainly, sources of cold water. A core group of enthusiastic landowners could begin implementing the best management practices and undertaking the necessary water quality improvement projects that could turn this stream around and make it a coldwater treasure. An organized effort is currently underway to do just that. Visit Trout Unlimited’s Don Fritchey Chapter and Donegal Chapter to learn more. Better yet, join them as a volunteer or cooperating landowner!

For coldwater fishes, the thousands of years since the most recent glacial maximum have seen their range slowly contract from nearly the entirety of the once much larger Susquehanna watershed to the headwaters of only our most pristine streams. Through no fault of their own, they had the misfortune of bad timing—humans arrived and found coldwater streams and the groundwater that feeds them to their liking. Some of the later arrivals even built their houses right on top of the best-flowing springs. Today, populations of these fishes in the region we presently call the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are seriously disconnected and the prospect for survival of these species here is not good. Stream rehabilitation, groundwater management, and better civil planning and land/water stewardship are the only way coldwater fishes, and very possibly coolwater fishes as well, will survive. For some streams like Hammer Creek, it’s not too late to make spectacular things happen. It mostly requires a cadre of citizens, local government, project specialists, and especially stakeholders to step up and be willing to remain focused upon project goals so that the many years of work required to turn a failing stream around can lead to success.

You’re probably glad this look at heat flux processes in streams has at last come to an end. That’s good, because we’ve got a lot of work to do.

It was dubbed the “Great Solar Eclipse”, the Great North American Eclipse”, and several other lofty names, but in the lower Susquehanna valley, where about 92% of totality was anticipated, the big show was nearly eclipsed by cloud cover. With last week’s rains raising the waters of the river and inundating the moonscape of the Pothole Rocks at Conewago Falls, we didn’t have the option of repeating our eclipse observations of August, 2017, by going there to view this year’s event, so we settled for the next best thing—setting up in the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters garden. So here it is, yesterday’s eclipse…

At just after 8:30 this evening, an Antares rocket carrying a Cygnus supply capsule launched from the NASA flight facility on Delmarva Peninsula at Wallops Island, Virginia. We took a walk on the Veterans Memorial Bridge over the Susquehanna at Columbia-Wrightsville to have a look at the spacecraft as it powered its way into orbit for a rendezvous with the International Space Station.

Unfortunately, a smoky haze from wildfires still burning in Canada obscured our view of the ascending rocket as it cleared our horizon and made its way downrange across the Atlantic.

But on the brighter side, we were spared any significant disappointment. It just so happened that the Antares/Cygnus rocket wasn’t the only launch visible from the Veteran’s Memorial Bridge this evening…

Fifty years ago, the world’s attention was fixed on the fate of the Apollo 13 astronauts—Commander Jim Lovell, Lunar Module Pilot Fred Haise, and Command Module Pilot Jack Swigert—after an explosion disabled their spacecraft and changed a mission to explore the moon into an improvised operation to return them safely to the earth. Perhaps this anniversary comes at a fortuitous time. The story of Apollo 13 may have parallels and lessons pertinent to present-day events and the concerns of people in America and around the world.

In April, 1970, Jack Swigert was a last-minute replacement for the original Apollo 13 Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly after Mattingly was exposed to German measles (rubella) prior to the mission. Mattingly had been training with fellow backup crew members John Young and Charles Duke when Duke came down with the disease after he and his family had visited friends whose three-year-old son was suffering the effects of the infection. NASA was wary of contagions that could spread among the astronauts while isolated in a space capsule during a lengthy journey, possibly incapacitating the entire crew. Tests on the astronauts found that Mattingly, like Duke, had lacked antibodies to the rubella virus and could therefore become ill during the flight. Mattingly alone could get sick—Lovell and Haise, possessing resistance to rubella, could not. Nevertheless, the decision was made to substitute Swigert for Mattingly. Swigert proved competent for the late change partly because he had developed many of the emergency procedures for operating the Command Module. Mattingly, who never did get measles, along with Duke and Young, would be the crew for the Apollo 16 moon landing in April, 1972.

Apollo 13 was launched as scheduled on April 11, 1970, at 2:13 P.M. E.S.T. and was on its way to a planned third landing on the lunar surface.

After two successful landings, network television found no sensation in the story of yet another trip to the moon. There was little coverage of the mission’s first fifty-five hours. Then, fifty-five hours and just more than fifty-five minutes into the flight, and just two minutes after fulfilling Mission Control’s request to turn on fans to stir the oxygen tanks so that their contents could be measured, Jack Swigert radioed, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” Then Lovell repeated his message, “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” Within a minute, Fred Haise was listing some metering anomalies and alarm activations for Mission Control and added, “And we had a pretty large bang associated with the caution and warning there.” Apollo 13 was about 205,000 miles from earth—it was just after 10 P.M. E.S.T., April 13, 1970.

Thirteen minutes after the “bang”, Lovell radioed Mission Control while looking out the capsule’s window, “We are venting something out into the…into space.” Apollo 13 was losing it’s oxygen, and its electric supplies. They didn’t know it at the time, but oxygen tank number two had exploded and damaged either a valve or tubing on tank number one—the Command Module’s only other source of oxygen—and both were losing their contents into space. Two of the three fuel cells had failed as well. Without oxygen, the remaining fuel cell in the Service Module would fail to make electricity for operation of the Command Module. Worse yet, the astronauts would not be able to breathe. Without delay, engineers and scientists on the ground went into action to develop alternatives to the original flight plan.

Power in the Command Module had to be conserved for reentry, so with just fifteen minutes of electricity remaining, Lovell and Haise moved into the “lifeboat”, the Lunar Module, and began powering it up while Swigert finished shutting down the systems aboard Odyssey to conserve its remaining energy for the end of the mission. Haise, who had spent fourteen months at Grumman’s manufacturing facility on Long Island, was intimately familiar with the Lunar Module’s operating systems. He powered-up essential systems and began calculating whether the consumables on Aquarius would last for the time it would take to go around the moon and “slingshot” back to earth.

To change the course of Apollo 13 from a moon orbit trajectory to one that would whip around the back of the moon and send them home, Lovell used the Lunar Module’s descent engine to perform a 35-second-long course correction burn. This burn commenced five hours after the explosion at 3:43 A.M. E.S.T. on the morning of April 14. Apollo 13 was then on a free-return trajectory to loop around the moon and return to earth.

Haise had in his possession notes from previous missions which he consulted to determine that they would run out of water about five hours before returning to earth. Fortunately, his notes also showed that the spacecraft’s mechanical systems could remain viable without water cooling for seven or eight hours. Astronauts reduced their water intake to six ounces a day, one fifth of normal, and attempted to compensate by drinking fruit juices and eating wet-packed hot dogs and similar foods. Their efforts to conserve water succeeded, but did lead to the crew becoming dehydrated.

For breathing, there was a sufficient supply of oxygen in the Lunar Module ascent stage where the astronauts would be taking refuge for the remaining four days of the journey. As a backup, there was oxygen in the two suits that were intended for the moonwalk and two more tanks in the ascent stage of Aquarius. Less than half of the oxygen supply was used during the return trip.

Procedures worked out by engineers and tested in a simulator on the ground allowed the crew to use only one fifth of the power normally required during the Lunar Module’s intended forty-five hours of useful life, thus enabling its batteries to last for a ninety-hour-long return trip and add charge to the Command Module batteries—with some energy to spare. To make it back to earth within the ninety-hour time window, the return trip would need to be shortened by nine hours.

The trajectory of Apollo 13’s loop behind the moon had carried them further away from earth than any other humans have ever gone. Two hours after swinging around the moon, Lovell prepared to perform a second burn with the Lunar Module’s descent engine—five minutes in duration—to increase Apollo 13’s return speed and shorten the time it would take to get back home. For navigational alignment during the burn maneuver, debris around the spacecraft made using the sextant to sight stars impossible. Scientists on the ground came up with coordinates allowing Lovell to use the sun as a navigation reference instead. The burn was a success.

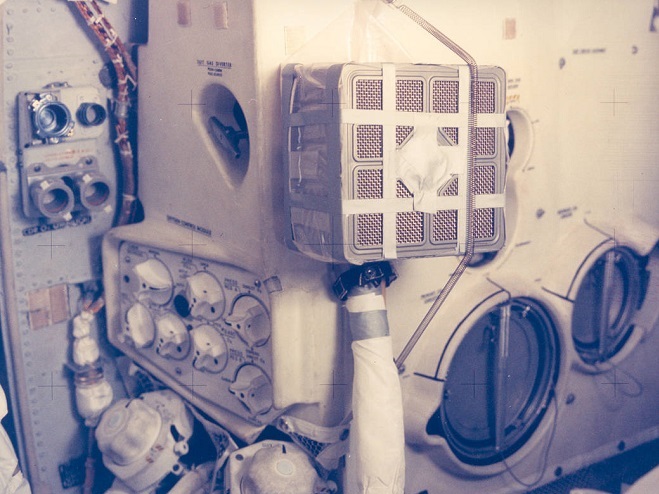

Lithium hydroxide canisters remove the carbon dioxide gas, which is continuously produced by the respiration of the astronauts, from the atmosphere of a spacecraft. The Lunar Module’s canisters were designed to protect two astronauts for two days. Because it was being used as a “lifeboat”, Aquarius was hosting three astronauts for four days. After one and a half days of use by three men, an alarm warned that the carbon dioxide levels in the Lunar Module were getting dangerously high. Spare canisters from Odyssey could be used, but there was a problem—they were square, those used on Aquarius were round.

Engineers on the ground went to work using materials that would be available aboard the Apollo 13 spacecraft to improvise a solution. They came up with an adapter design using duct tape, a plastic bag, and cardboard to fabricate a “mailbox” that would attach square lithium hydroxide canisters to the round air handling tubes in the Lunar Module. After testing on the ground, the detailed verbal instructions for constructing the life-saving invention were radioed by Joe Kerwin from Mission Control to Aquarius. Haise and Swigert assembled and installed two of the life-saving devices. Carbon dioxide levels soon dropped back within acceptable parameters.

The astronauts endured a lack of sleep, heat, water, and food during the trip home. All were dehydrated and collectively they lost over thirty pounds of body weight. As they approached earth, the crew prepared to implement the new procedures for re-energizing the cold damp systems of the Command Module. Ground personnel had drafted and tested this set of startup instructions in just three days instead of the thirty days that such work usually requires. It was critical that the circuits that were energized did not collectively exceed the amperage available from the batteries on Odyssey.

Jack Swigert carefully brought Odyssey back to life using the new procedures, which were radioed, step by step, from Mission Control. Short circuits, feared due to the moisture that had condensed on all the cold surfaces in the Command Module, were not a problem. Improvements to the insulation on the wiring and electrical components throughout the interior of the space capsules following the Apollo 1 fire is believed to have safeguarded against any mishaps.

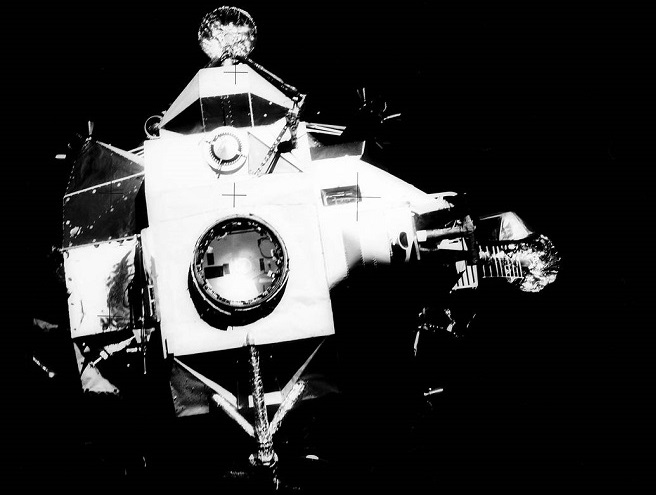

Four hours before reentry, at 8:15 A.M. E.S.T. on April 17, 1970, the Service Module was jettisoned and photographed as the crew got its first look at the damage caused by the explosion. Just an hour before reentry, Lovell and Haise joined Swigert in the Command Module. At 11:43, the Lunar Module was jettisoned and drifted away.

Apollo 13 reentered earth’s atmosphere and experienced the usual communications blackout as the capsule sizzled through an envelope of ionized air. Mission Control and the world rejoiced as cameras televised images of deployed parachutes and a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean less than four miles from the recovery ship, the U.S.S. Iwo Jima, at 1:08 P.M. E.S.T. Possibly as many as one billion people were watching.

The families of the astronauts had traveled aboard Air Force One along with President Richard Nixon to Honolulu, Hawaii, and were waiting for the Apollo 13 crew when they arrived there from American Samoa on April 18. Nixon presented the men with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“…The men of Apollo 13, by their poise and skill under the most intense kind of pressure, epitomize the character that accepts danger and surmounts it…Theirs is the spirit that built America.”

Among the greatest legacies of the earth orbit and moon missions were the scientific and technological achievements that allowed people to live and travel in space using a minimum of resources. Apollo 13 took these minimums to the extreme—using everything as effectively and efficiently as possible. It was one of the pinnacle achievements of the manned spaceflight program.

Fifty years later, are we embracing these and more recent innovations to live comfortably but wisely?

President John F. Kennedy, in his 1962 speech at Rice University, beckoned Americans to strive for a seemingly unreachable goal. A goal that would motivate a people to determine their own destiny and not have destiny determined for them.

“…We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone…”

Kennedy urged his country to take the risk and go to the moon. Despite the dangers, despite the hesitations of the medical community, and in spite of the naysayers, they accepted the challenge and succeeded.

Have Americans lost the will to shape their own destiny? Are they content with blind obedience, mediocrity, and shopping with a dirty rag over their face? Let your friendly editor give you a hint. The people who happen to be front and center in the news today, fifty years after Apollo 13, aren’t rocket scientists. In fact, they have a hard time swallowing anything science has to offer, unless, of course, it can be twisted to back up their sneaky little schemes. But they’re the leadership—elected dimwits and entrenched bureaucrats—and they rule by consent of the governed. So the matter is decided. Look at the bright side though, at least the creeps have a career to protect, so we’ll always be certain of their motivation.

SOURCES

Lovell, James A. 1975. “Houston, We’ve Had A Problem; A Crippled Bird Limps Safely Home”. Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, DC. pp. 247-263.

SOURCES THAT APPARENTLY NOBODY READS

Broseau, Lisa M., and Margaret Seitsema. 2020. “Commentary: Masks-for-all for COVID-19 Not Based on Sound Data”. University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Policy https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/04/commentary-masks-all-covid-19-not-based-sound-data Accessed April 10, 2020.

Davies, Anna, Katy-Anne Thompson, Karthika Giri, George Kafatos, Jimmy Walker, and Alan Bennett. 2013. “Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic?”. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 7:4. pp. 413-418.

MacIntyre, C. Raina, Holly Seale, Tham Chi Dung, Nguyen Tran Hien, Phan Thi Nga, Abrar Ahmad Chughtai, Bayzidur Rahman, Dominic E. Dwyer, and Quanyi Wang. 2015. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Cloth Masks Compared with Medical Masks in Healthcare Workers. BMJ Open. 5:e006577. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577.

As spring begins, our thoughts often turn, if only briefly, to the sun and the welcome effect its higher angle in the sky and the lengthening hours of daylight will have on our winter-weary lives. Soon, spring thunderstorms and warm humid air will make our crops thrive. Plant buds will open to reveal flowers and leaves, and wildlife will hurry to raise a new generation. We’re reminded that the sun is the source of earth’s life—and is its ongoing benefactor.

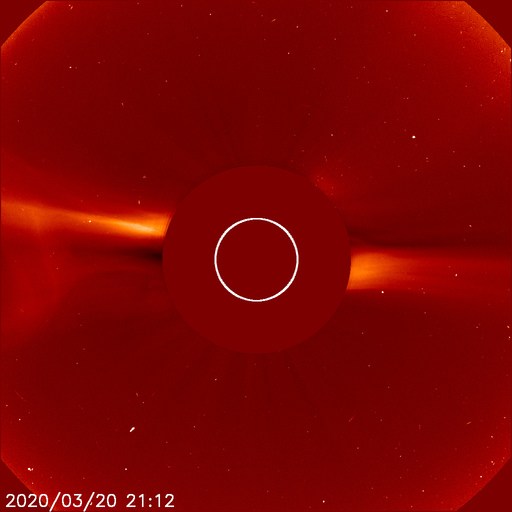

Coincidentally, there was, during the first full day of spring, an explosion of plasma from the sun—a Coronal Mass Ejection. It happened to occur on the side of the sun currently facing away from earth, so the enormous cloud of magnetic energy won’t be affecting radio communications or electric transmission here.

Friday’s Coronal Mass Ejection can be seen in the following series of images. To protect the camera’s sensor, the direct light of the sun was blocked by an occulter at the center of each picture. The location of the sun’s disk is indicated by the white circle. In this set, the ejected plasma appears as a cloud emerging from behind the left side of the shield and racing millions of miles into space. The speed of a plasma cloud produced by a Coronal Mass Ejection varies. When directed at earth, some can reach our planet in less than a day—others may take several days to arrive.

Currently though, the term “Coronal Mass Ejection” may cause one to bristle and think of concerns other than the cosmos—Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the Wuhan flu chief among them.

Well, perhaps the promise of warming weather and humid days will help assuage our anxieties.

Colds and flu are certainly more prevalent in winter than during the other seasons of the year. Cases of these diseases begin creeping through schools and workplaces just in time for the year-end holidays. They persist into early spring each year. Then, as we spend more time outdoors in the sunshine and fresh air of April and May, their incidence wanes. Soon the sneezing and coughing is mostly pollen-related and less often the result of transmitted viruses.

In addition to our liberation from buildings crowded with people, spring heat introduces another factor that is apparently responsible for subduing the rapid transmission of viruses—humidity. February and March are typically the driest months of the year in the lower Susquehanna valley. The air outside is cold and dry. The air inside a heated building can be worse.

Researchers have found that viruses in aerosols produced by coughing, sneezing, breathing, and talking survive longer in drier air than in humid air. A NIOSH and CDC funded study (Noti, et al., 2013) mechanically “coughed” aerosols containing H1N1 virus into a simulated examination room. They discovered that “…one hour after coughing, ∼5 times more virus remains infectious at 7-23% RH (relative humidity) than at ≥43% RH.” This is a significant discovery and may shed light on why the end of heating season and the arrival of warmer humid springtime air coincides with the end of cold and flu season. The study’s analysis determined that “Total virus collected for 60 minutes retained 70.6-77.3% infectivity at relative humidity ≤23%, but only 14.6-22.2% at relative humidity ≥43%.” Specifically, they found that the greatest effect of higher relative humidity occurs during the first fifteen minutes after the cough, and that virus in droplets exceeding 4μM in diameter had the most significant reduction in that time—ninety percent.

It looks like a little global warming wouldn’t hurt right now.

So remember, respect the sun—fear asteroids.

SOURCES

Burnham, Robert, Alan Dyer, Robert A. Garfinkle, Martin George, Jeff Kanipe, and David H. Levy. 2006. The Nature Companions Practical Skywatching. Fog City Press. San Francisco, CA.

Noti, J.D., F. M. Blachere, C. M. McMillen, W. G. Lindsley, M. L. Kashon, D. R. Slaughter, et al. 2013. “High Humidity Leads to Loss of Infectious Influenza Virus from Simulated Coughs”. PLoS ONE. 8:2 e57485. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057485

It’s a hot summer weekend with a sun so bright that creosote is dripping from utility poles onto the sidewalks. Dodging these sticky little puddles of tar can cause one to reminisce about sultry days-gone-by.

Sometime in July or August each year, about half a century ago, we would cram all the gear for seven days of living into the car and head for the beaches of Delmarva or New Jersey. It was family vacation time, that one week a year when the working class fantasizes that they don’t have it so bad during the other fifty-one weeks of the year.

The trip to the coast from the Susquehanna valley was a day-long journey. Back then, four-lane highways were few beyond the cities of the northeast corridor and traffic jams stretched for miles. Cars frequently overheated and steam rolled from beneath the hoods of those stopped to cool down. There were even 55-gallon drums of non-potable water positioned at known choke points along some of the state roads so that motorists could top off their radiators and proceed on. Within these back-ups there were many Volkswagen Beetles pausing along the side of the road with the rear hood propped up. Their air-cooled engines would overheat on a hot day if the car wasn’t kept moving. But, despite the setbacks, all were motivated to continue. In time, with perseverance, the smell of saltmarsh air was soon rolling in the windows. Our destination was near.

At the shore, priority one was to spend plenty of time at the beach. Sunbathers lathered up with various concoctions of oils and moisturizers, including my personal favorite, cocoa butter, then they broiled themselves in the raging rays of the fusion-reaction furnace located just eight light-minutes away. Reflected from the white sand and ocean surf, the flaming orb’s blinding light did a thorough job of cooking all the thousands of oil-basted sun worshippers packing the tidal zone for miles and miles. You could smell the hot cocoa butter in the summer air as they burned. Well, maybe not, but you could smell something there.

By now, you’re probably saying, “Hey, why weren’t you idiots wearing protection from the sun’s harmful U.V. rays?”

Good question. Uncle Tyler Dyer reminds me that back in the sixties, a sunscreen was a shade hung to cover a window. He continued, “Man, the only sun block we had was a beach ball that happened to pass between us and the sun.”

During several of our summertime beach visits in the early 1970s, we got a different sort of oil treatment—tar balls. We never noticed the things until we got out of the water. Playing around at the tide line and taking a tumble in the surf from time to time, we must have picked them up when we rolled in the sand.

Uncle Ty wasn’t happy, “Man, they’re sticking all over our legs and feet, and look at your swim trunks, they’re ruined. And look in the sand, they’re everywhere.” The event was one of the seeds that would in time grow into Uncle Ty’s fundamental distrust of corporate culture.

Looking around, tar balls were all over everyone who happened to be near the water. Rumor on the beach was that they came from ships that passed by offshore earlier in the day. The probable source was the many oil spills that had occurred in the Mid-Atlantic region in those years. During the first six months of 1973 alone, there were over 800 oil spills there. Three hundred of those spills occurred in the waters surrounding New York City. The largest, almost half a million gallons, occurred in New York Harbor when a cargo ship collided with the tanker “Esso Brussels”. Forty percent of that spill burned in the fire that followed the mishap, the remainder entered the environment.

When it was time to clean up, we slowly removed the tar from our legs and feet by rubbing it away with a rag soaked in charcoal lighter fluid or gasoline. Needless to say, our skin turned redder than it had already been from sunburn.

After a full day in the surf, we’d be on our way back to our “home base” for summer vacation, a campground nestled somewhere in the pines on the mainland side of the tidal marshes behind our beach’s barrier island. There, we’d shake the sand out of our trunks and savor the feeling of dry clothing. As the sun set, the smoke, flicker, and crackle of dozens of campfires filled the spaces between the tents and camping trailers. Colored lights strung around awnings dazzled sun-weary eyes as night descended across the landscape. We’d commence the process of incinerating some marshmallows soon after. Then, sometime while we were roasting our weenies and warming our buns, we’d hear it.

His device didn’t have a very good muffler. It sounded like a rusty old lawn mower running on the back of a rusty old truck that didn’t sound much better. And you could see the cloud rising above the campsites around the corner as he approached. It was the mosquito man, come to rid the place of pesky nocturnal biting insects. Behind him, always, were young boys on bicycles riding in and out of the fog of insecticide that rolled from the back of the truck.

One was wise to quickly eat your campfire food and put the rest away before the fog rolled in. You had just minutes to choke down that burned up hot dog. Then the sense of urgency was gone. Everyone just sat around at picnic tables and on lawn chairs bathing in the airborne cloud. A thin layer of insecticide rubbed into the skin along with the liberal doses of Noxzema being applied to soothe sunburn pain will get you through the night just fine.

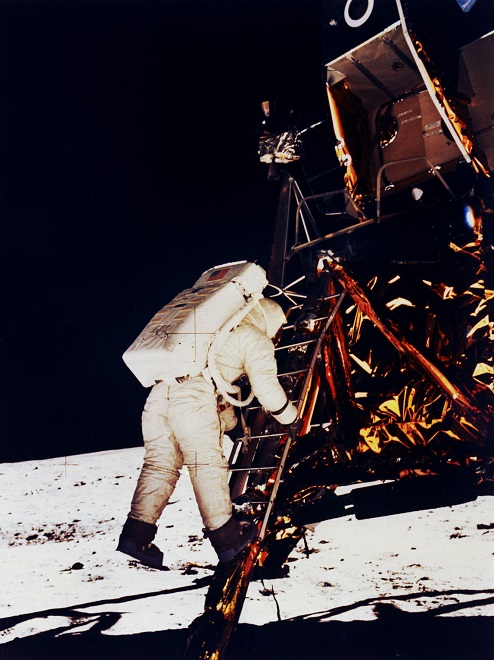

Perhaps the most memorable event to occur during our summer vacations happened at the moment of this writing, fifty years ago.

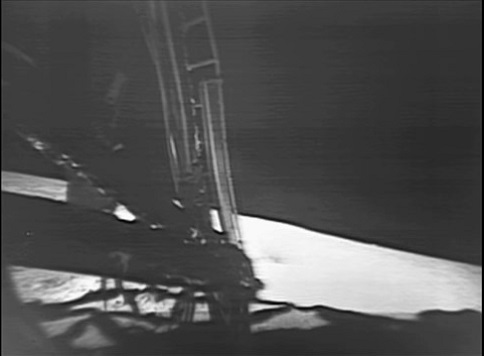

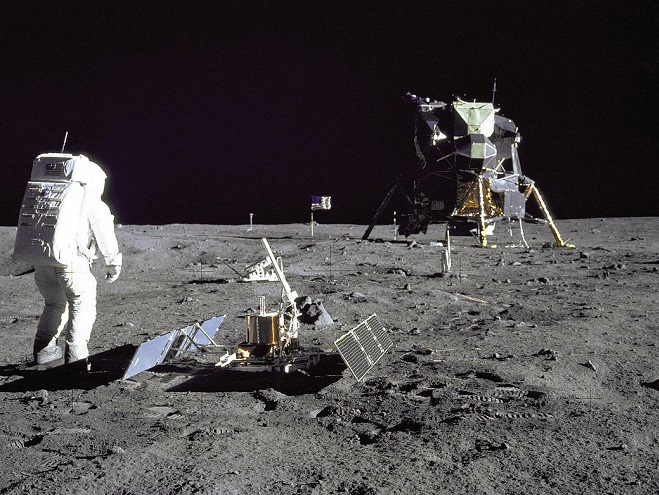

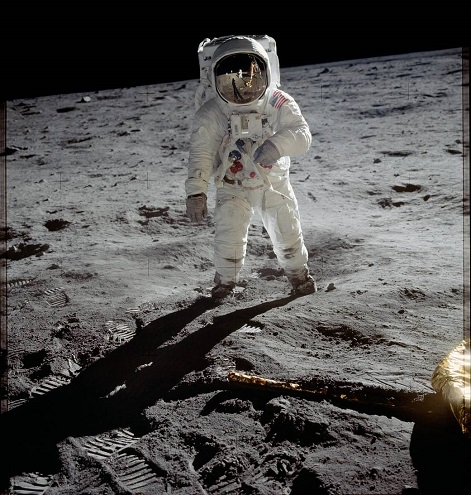

We were vacationing in a campground in southern New Jersey. Our family and the family of my dad’s co-worker gathered in a mosquito-mesh tent surrounding a small black-and-white television. An extension cord was strung to a receptacle on a nearby post, and the cathode ray tube produced the familiar picture of glowing blue tones to illuminate the otherwise dark scene. There was constant experimentation with the whip antenna to try to get a visible signal. There were no local UHF broadcasters and the closest VHF television stations were in Philadelphia, so the picture constantly had “snow” diminishing its already poor clarity. But we could see it, and I’ll never forget it.

SOURCES

Andelman, David A. “Oil Spills Here Total 300 in ’73”. The New York Times. August 8, 1973. p.41.

Cortright, Edgar M. (Editor). 1975. Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, DC.

Fifty years ago, the crew of Apollo 8 became the first humans to leave Earth and journey to its closest celestial body, the Moon. Launching on the morning of December 21, 1968, they were the first to enter space from atop the powerful and complex Saturn V rocket. Their eyes would be the first to see the Earth as an entire sphere and to orbit the Moon and observe its obscure far side. For many back home, they changed not only the way we understand the Moon, but how we perceive the uniqueness and fragility of Earth.

Said Command Module Pilot Jim Lovell during a televised broadcast from lunar orbit on Christmas Eve half a century ago, “The vast loneliness up here of the Moon is awe-inspiring, and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth. The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the big vastness of space.”

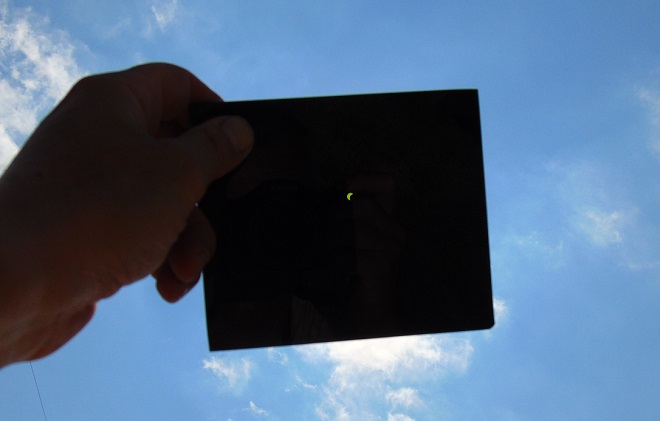

Was there a better place to have a look at the dark side of the moon easing across the summer sun than from the Pothole Rocks at Conewago Falls? O.K., alright, so there must have been a venue or two with bigger crowds, grand emotions, prepared foods, and near darkness, but the pseudolunar landscape of the falls seemed like an ideal observation point for the great North American solar eclipse of 2017.

Being the only person on the entire falls had its advantages, not the least of which was the luxury of pointing the camera directly at the sun and clicking off a few shots without getting funny looks and scolding comments. Priceless solitude.

If you think it looks like the above photograph was taken in a house of mirrors, then you’re pretty sharp. You’ve got it figured out. After getting a bad case of welder’s burns on the first day of a job at a metal fabricating shop during my teen years, I learned the value of a four dollar piece of glass.

For those of you who prefer not to look at the sun, even with protection (I heard those S.P.F. 30 sunblock eye drops were a fraud…I hope you didn’t buy any.), here is the indirect viewing method as it happened today.

If you were to our south in the path of totality for this eclipse, you probably noted reactions by flora and fauna. Here, there was really not much to report. The leaves of Partridge Pea didn’t fold for the night, birds didn’t fly away to roost, and the chorus of evening and nighttime singing insects didn’t get cranked up. The only sensation was the reduced brightness of the sun, as if a really dark cloud was filtering the light without changing its color or eliminating shadows. And that was the great solar eclipse of 2017.