Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

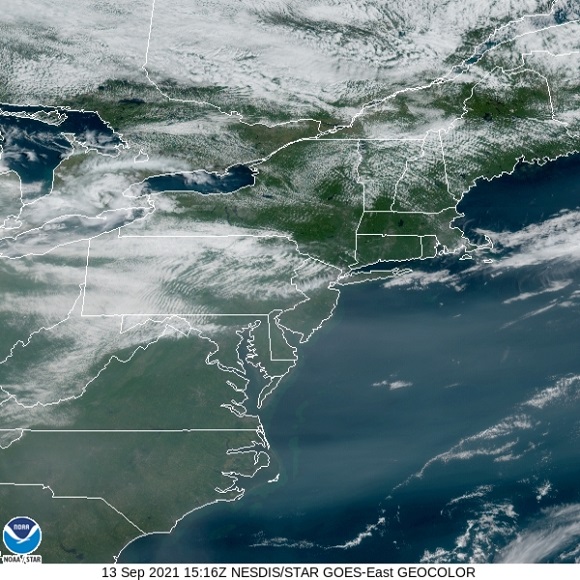

National Weather Service radar showed a sizeable nocturnal flight of migrating birds early this morning. Let’s go for a short stroll and see what’s around.

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

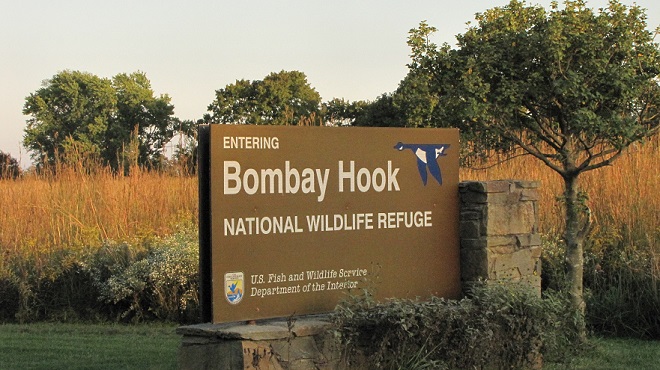

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

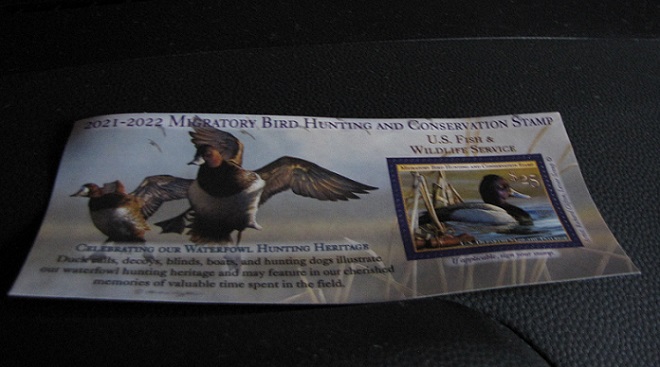

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

Can it be that time already? Most Neotropical birds have passed through the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed on their way south and the hardier species that will spend our winter in the more temperate climes of the eastern United States are beginning to arrive.

Here’s a gallery of sightings from recent days…

Be sure to click on these tabs at the top of this page to find image guides to help you identify the dragonflies, birds, and raptors you see in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed…

See you next time!

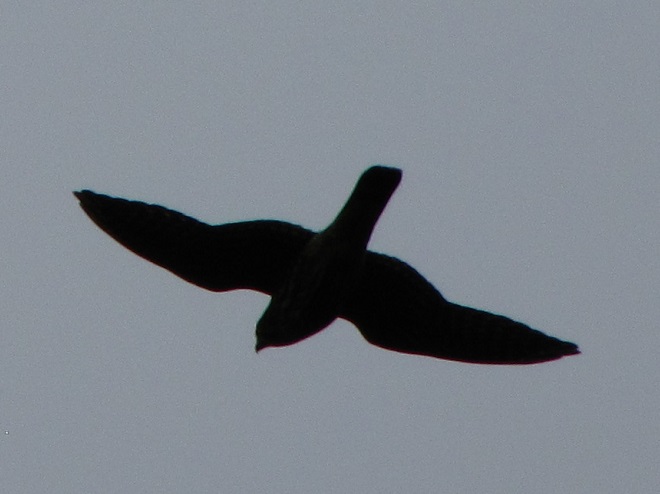

During the coming two weeks, peak numbers of migrating Neotropical birds will be passing through the northeastern United States including the lower Susquehanna valley. Hawk watches are staffed and observers are awaiting big flights of Broad-winged Hawks—hoping to see a thousand birds or more in a single day.

Broad-winged hawks feed on rodents, amphibians, and a variety of large insects while on their breeding grounds in the forests of the northern United States and Canada. They depart early, journeying to wintering areas in Central and South America before frost robs them of a reliable food supply.

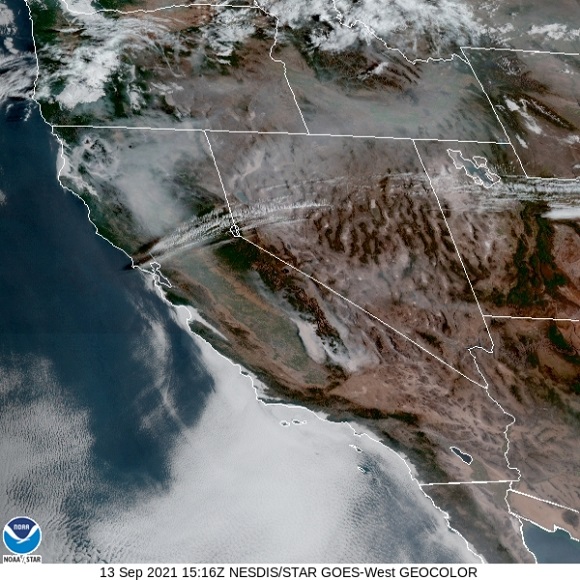

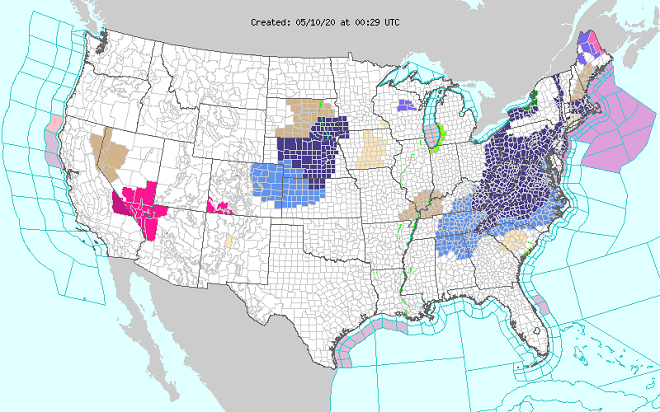

While migrating, Broad-winged Hawks climb to great altitudes on thermal updrafts and are notoriously difficult to see from ground level. Bright sunny skies with no clouds to serve as a backdrop further complicate a hawk counter’s ability to spot passing birds. Throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the coming week promises to be especially challenging for those trying to observe and census the passage of high-flying Broad-winged Hawks. The forecast of hot and humid weather is not so unusual, but the addition of smoke from fires in the western states promises to intensify the haze and create an especially irritating glare for those searching the skies for raptors.

It may seem gloomy for the mid-September flights in 2021, but hawk watchers are hardy types. They know that the birds won’t wait. So if you want to see migrating “Broad-wings” and other species, you’ve got to get out there and look up while they’re passing through.

These hawk watches in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are currently staffed by official counters and all welcome visitors:

—or you can just keep an eye on the sky from wherever you happen to be. And don’t forget to check the trees and shrubs because warbler numbers are peaking too! During recent days…

Neotropical birds are presently migrating south from breeding habitats in the United States and Canada to wintering grounds in Central and South America. Among them are more than two dozen species of warblers—colorful little passerines that can often be seen darting from branch to branch in the treetops as they feed on insects during stopovers in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Being nocturnal migrants, warblers are best seen first thing in the morning among sunlit foliage, often high in the forest canopy. After a night of flying, they stop to feed and rest. Warblers frequently join resident chickadees, titmice, and nuthatches to form a foraging flock that can contain dozens of songbirds. Migratory flycatchers, vireos, tanagers, and grosbeaks often accompany southbound warblers during early morning “fallouts”. Usually, the best way to find these early fall migrants is to visit a forest edge or thicket, particularly along a stream, a utility right-of-way, or on a ridge top. Then too, warblers and other Neotropical migrants are notorious for showing up in groves of mature trees in urban parks and residential neighborhoods—so look up!

Be sure to visit the Birds of Conewago Falls page by clicking the “Birds” tab at the top of this page. There, you’ll find photographs of the birds, including warblers and other Neotropical migrants, that you’re likely to encounter at locations throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

You’ll want to go for a walk this week. It’s prime time to see birds in all their spring splendor. Colorful Neotropical migrants are moving through in waves to supplement the numerous temperate species that arrived earlier this spring to begin their nesting cycle. Here’s a sample of what you might find this week along a rail-trail, park path, or quiet country road near you—even on a rainy or breezy day.

It’s just common sense to take it easy and drive carefully when snow covers streets and highways. Everyone knows that. But did you know that slowing down when the landscape is blanketed in white can save lives even after the roadways have been cleared?

Following significant snowfalls such as the one earlier this week, birds and other wildlife are attracted to bare ground along the edges of plowed pavement. They are often so preoccupied with the search for food that they ignore approaching cars and trucks until it is too late.

Take a look at the species found today along a one mile stretch of plowed rural roadway in the lower Susquehanna valley.

For many species of wildlife in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, the fragmented and impaired state of habitat already challenges their chances of surviving the winter. Snow cover can isolate them from their limited food supplies and force them to roadsides and other dangerous locations to forage. Mauling them with motor vehicles just adds to the escalating tragedy, so do wildlife and yourself a favor—please slow down.

Thoughts of October in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed bring to mind scenes of brilliant fall foliage adorning wooded hillsides and stream courses, frosty mornings bringing an end to the growing season, and geese and other birds flying south for the winter.

The autumn migration of birds spans a period equaling nearly half the calendar year. Shorebirds and Neotropical perching birds begin moving through as early as late July, just as daylight hours begin decreasing during the weeks following their peak at summer solstice in late June. During the darkest days of the year, those surrounding winter solstice in late December, the last of the southbound migrants, including some hawks, eagles, waterfowl, and gulls, may still be on the move.

During October, there is a distinct change in the list of species an observer might find migrating through the lower Susquehanna valley. Reduced hours of daylight and plunges in temperatures—particularly frost and freeze events—impact the food sources available to birds. It is during October that we say goodbye to the Neotropical migrants and hello to those more hardy species that spend their winters in temperate climates like ours.

The need for food and cover is critical for the survival of wildlife during the colder months. If you are a property steward, think about providing places for wildlife in the landscape. Mow less. Plant trees, particularly evergreens. Thickets are good—plant or protect fruit-bearing vines and shrubs, and allow herbaceous native plants to flower and produce seed. And if you’re putting out provisions for songbirds, keep the feeders clean. Remember, even small yards and gardens can provide a life-saving oasis for migrating and wintering birds. With a larger parcel of land, you can do even more.

If it can fly, there’s a pretty good chance it was at Second Mountain today.

What follows is a photographic chronology of some of today’s sightings at Second Mountain Hawk Watch at Fort Indiantown Gap in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. We begin with some of the hundreds of migratory songbirds found at the base of the mountain along Cold Spring Road near Indiantown Run during the early morning, then we continue to the lookout for the balance of the day.

The total number of Broad-winged Hawks observed migrating past the Second Mountain lookout today was 619. To see the daily raptor counts for Second Mountain and other hawk watches in North America, and to learn more about each site, be sure to visit hawkcount.org

Okay, so it happened to be cloudy with drizzle at sunrise—not the best conditions for observing birds in the treetops. But that inclement weather effectively grounded the overnight flight of migrating songbirds leading to a really big fallout in the lower Susquehanna valley this morning.

While straining one’s neck to gaze up into the forest canopy, hundreds of migrants including warblers, vireos, tanagers, thrushes, and flycatchers could be seen. Identifying each was impossible.

Here are of few of this morning’s arrivals. Manually setting the camera to a slower shutter speed compensated a little bit for the backlighting caused by cloudy conditions.

Peak numbers of Broad-winged Hawks will pass through the area during the coming two weeks. They most often migrate in groups, with sizes ranging from several individuals to hundreds or even thousands of birds. Despite this being a less than ideal day for riding thermals and gliding off towards the southwest to continue their journey to the tropics, some “broad-wings” ventured aloft and were on their way soon after the drizzle subsided during mid-morning.

The southbound bird migration of 2020 is well underway. With passage of a cold front coming within the next 48 hours, the days ahead should provide an abundance of viewing opportunities.

Here are some of the species moving through the lower Susquehanna valley right now.

Today’s arrivals—Neotropical migrants found in a streamside thicket in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed this morning…

After nearly a full week of record-breaking cold, including two nights with a widespread freeze, warm weather has returned. Today, for the first time this year, the temperature was above eighty degrees Fahrenheit throughout the lower Susquehanna region. Not only can the growing season now resume, but the northward movement of Neotropical birds can again take flight—much to our delight.

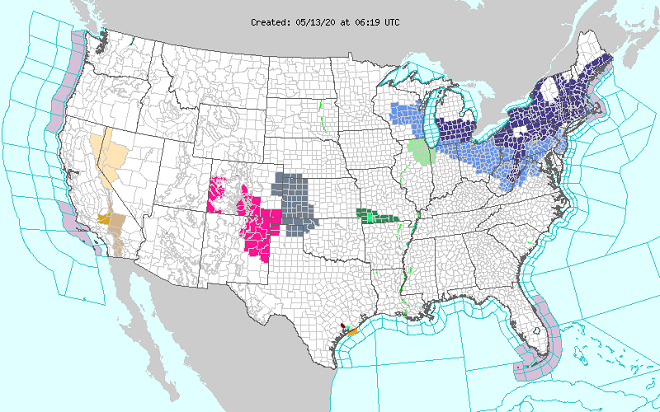

A rainy day on Friday, May 8, preceded the arrival of a cold arctic air mass in the eastern United States. It initiated a sustained layover for many migrating birds.

Freeze warnings were issued for five of the next six mornings. The nocturnal flights of migrating birds, most of them consisting of Neotropical species by now, appeared to be impacted. Even on clear moonlit nights, these birds wisely remained grounded. Unlike the more hardy species that moved north during the preceding weeks, Neotropical birds rely heavily on insects as a food source. For them, burning excessive energy by flying through cold air into areas that may be void of food upon arrival could be a death sentence. So they wait.

Today throughout the lower Susquehanna region, bird songs again fill the air and it seems to be mid-May as we remember it. The flights have resumed.

You need to get outside and go for a walk. You’ll be sorry if you don’t. It’s prime time to see wildlife in all its glory. The songs and colors of spring are upon us!

If you’re not up to a walk and you just want to go for a slow drive, why not take a trip to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area and visit the managed grasslands on the north side of the refuge. To those of us over fifty, it’s a reminder of how Susquehanna valley farmlands were before the advent of high-intensity agriculture. Take a look at the birds found there right now.

And remember, if you happen to own land and aren’t growing crops on it, put it to good use. Mow less, live more. Mow less, more lives.

For those of you who dare to shed that filthy contaminated rag you’ve been told to breathe through so that you might instead get out and enjoy some clean air in a cherished place of solitude, here’s what’s around—go have a look.

The springtime show on the water continues…

Hey, what are those showy flowers?

Wasn’t that refreshing? Now go take a walk.

It’s that time of year when one may expect to find migratory Neotropical songbirds feeding among the foliage of trees and shrubs in the forests, woodlots, and thickets of the lower Susquehanna valley.

During a late afternoon stroll through a headwaters forest east of Conewago Falls outside Mount Gretna, I was pleased to finally come upon a noisy gathering of about two dozen birds. It had, previous to that, been a quiet two hours of walking, only the rumble of an approaching thunderstorm punctuated the silence. Among this little flock were some chickadees, robins, Gray Catbirds, an Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus), and a Hairy Woodpecker (Dryobates villosus). Besides the catbirds, there were two other species of Neotropical migrants; both were warblers. No less than six Black-throated Blue Warblers (Setophaga caerulescens) were vying for positions in the trees from which they could investigate the stranger on the footpath below. And among the understory shrubs there were at least as many Ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla) satisfying a similar curiosity.

When they depart the Susquehanna valley, these two warbler species will be southbound for wintering ranges that include Florida, many of the Caribbean Islands, Central America, and, for the Ovenbirds, northern South America. Their flights occur at night. During the breeding season and while migrating, both feed primarily on insects and other arthropods . On the wintering grounds, they will consume some fruit. It is during their time in the tropics that the Black-throated Blue Warbler sometimes visits feeding stations that offer grape jelly, much to the delight of bird enthusiasts.

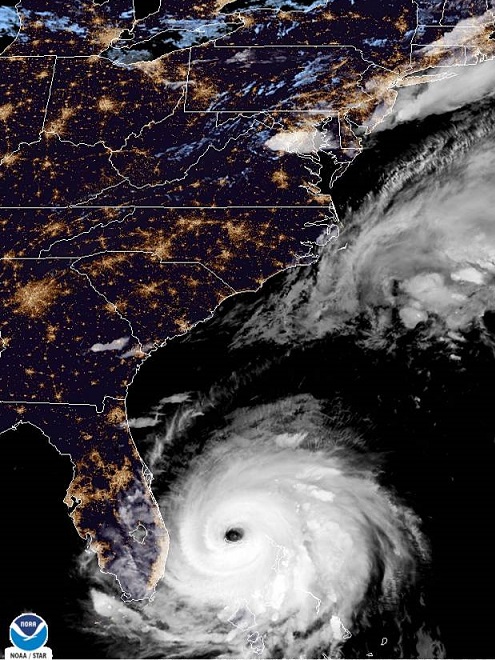

Black-throated Blue Warblers and Ovenbirds commonly winter on the Florida peninsula and in the Bahamas. With the major tropical cyclone Hurricane Dorian presently ripping through the region, these birds are better off taking their time getting there. There’s no need to hurry. The longer they and the other Neotropical migrants hang around, the more we get to enjoy them anyway. So get out there to see them before they go—and remember to look up.

One can get a stiff neck looking up at the flurry of bird activity in the treetops at this time of year. Many of the Neotropical migrants favor rich forests as daytime resting sites after flying through the night. For others, these forests are a destination where they will nest and raise their young.

For the birds that arrive earlier in spring than the Neotropical migrants, the breeding season is well underway. The wet weather may be impacting the success of the early nests.

So long for now, if you’ll excuse me please, I have a sore neck to tend to.

Temperatures plummeted to well below freezing during the past two nights, but there was little sign of it in Conewago Falls this morning. The fast current in the rapids and swirling waters in flooded Pothole Rocks did not freeze. Ice coated the standing water in potholes only in those rocks lacking a favorable orientation to the sun for collecting solar heat during the day to conduct into the water during the cold nights.

On the shoreline, the cold snap has left its mark. Ice covers the still waters of the wetlands. Frost on exposed vegetation lasted until nearly noontime in shady areas. Insect activity is now grounded and out of sight. The leaves of the trees tumble and fall to cover the evidence of a lively summer.

The nocturnal bird flight is narrowing down to just a few species. White-throated Sparrows, a Swamp Sparrow (Melospiza georgiana), and Song Sparrows are still on the move. Though their numbers are not included in the migration count, hundreds of the latter are along the shoreline and in edge habitat around the falls right now. Song Sparrows are present year-round, migrate at night, and are not seen far from cover in daylight, so migratory movements are difficult to detect. It is certain that many, if not all of the Song Sparrows here today have migrated and arrived here recently. The breeding population from spring and summer has probably moved further south. And many of the birds here now may remain for the winter. Defining the moment of this dynamic, yet discrete, population change and logging it in a count would certainly require different methods.

Diurnal migration was foiled today by winds from southerly directions and moderating temperatures. The only highlight was an American Robin flight that extended into the morning for a couple of hours after daybreak and totaled over 800 birds. This flight was peppered with an occasional flock of blackbirds. Then too, there were the villains.

They’re dastardly, devious, selfish, opportunistic, and abundant. Today, they were the most numerous diurnal migrant. Their numbers made this one of the biggest migration days of the season, but they are not recorded on the count sheet. It’s no landmark day. They excite no one. For the most part, they are not recognized as migrants because of their nearly complete occupation of North America south of the taiga. If people build on it or alter it, these birds will be there. They’re everywhere people are. If the rotten attributes of man were wrapped up into one bird, an “anthropoavian”, this would be it.

Meet the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris). Introduced into North America in 1890, the species has spread across the entire continent. It nests in cavities in buildings and in trees. Starlings are aggressive, particularly when nesting, and have had detrimental impacts on the populations of native cavity nesting birds, particularly Red-headed Woodpeckers, Purple Martins (Progne subis), and Eastern Bluebirds. They commonly terrorize these and other native species to evict them from their nest sites. European Starlings are one of the earlier of the scores of introduced plants and animals we have come to call invasive species.

Today, thousands of European Starlings were on the move, working their way down the river shoreline and raiding berries from the vines and trees of the Riparian Woodlands. My estimate is between three and five thousand migrated through during the morning. But don’t worry, thousands more will be around for the winter.

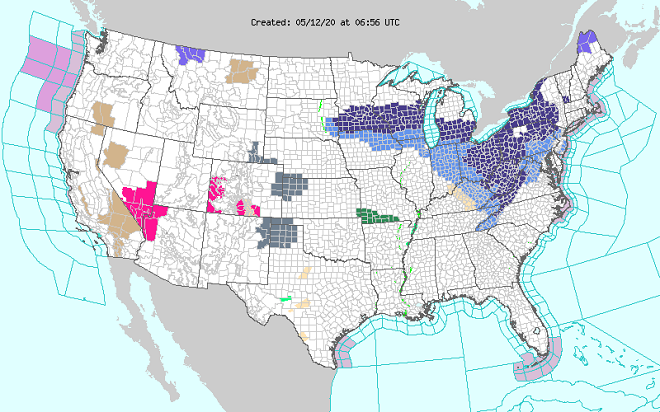

The NOAA National Weather Service radar images from last evening provided an indication that there may be a good fallout of birds at daybreak in the lower Susquehanna valley. The moon was bright, nearly full, and there was a gentle breeze from the north to move the nocturnal migrants along. The conditions were ideal.

The Riparian Woodlands at Conewago Falls were alive with migrants this morning. American Robins and White-throated Sparrows were joined by new arrivals for the season: Brown Creeper (Certhia americana), Ruby-crowned Kinglets (Regulus calendula), Golden-crowned Kinglets (Regulus satrapa), Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis), and Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata). These are the perching birds one would expect to have comprised the overnight flight. While the individuals that will remain may not yet be among them, these are the species we will see wintering in the Mid-Atlantic states. No trip to the tropics for these hardy passerines.

It was a placid morning on Conewago Falls with blue skies dotted every now and then by a small flock of migrating robins or blackbirds. The jumbled notes of a singing Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis) in the Riparian Woodland softly mixed with the sounds of water spilling over the dam. The season’s first Wood Ducks (Aix sponsa), Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors), American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus), Horned Larks (Eremophila alpestris), and White-throated Sparrows (Zonotrichia albicollis) were seen.

There was a small ruckus when one of the adult Bald Eagles from a local pair spotted an Osprey passing through carrying a fish. This eagle’s effort to steal the Osprey’s catch was soon interrupted when an adult eagle from a second pair that has been lingering in the area joined the pursuit. Two eagles are certainly better than one when it’s time to hustle a skinny little Osprey, don’t you think?

But you see, this just won’t do. It’s a breach of eagle etiquette, don’t you know? Soon both pairs of adult eagles were engaged in a noisy dogfight. It was fussing and cackling and the four eagles going in every direction overhead. Things calmed down after about five minutes, then a staring match commenced on the crest of the dam with the two pairs of eagles, the “home team” and the “visiting team”, perched about 100 feet from each other. Soon the pair which seems to be visiting gave up and moved out of the falls for the remainder of the day. The Osprey, in the meantime, was able to slip away.

In recent weeks, the “home team” pair of Bald Eagles, seen regularly defending territory at Conewago Falls, has been hanging sticks and branched tree limbs on the cross members of the power line tower where they often perch. They seem only to collect and display these would-be nest materials when the “visiting team” pair is perched in the nearby tower just several hundred yards away…an attempt to intimidate by homesteading. It appears that with winter and breeding time approaching, territorial behavior is on the increase.

In the afternoon, a fresh breeze from the south sent ripples across the waters among the Pothole Rocks. The updraft on the south face of the diabase ridge on the east shore was like a highway for some migrating hawks, falcons, and vultures. Black Vultures (Coragyps atratus) and Turkey Vultures streamed off to the south headlong into the wind after leaving the ridge and crossing the river. A male and female Northern Harrier (Circus hudsonius), ten Red-tailed Hawks, two Red-shouldered Hawks (Buteo lineatus), six Sharp-shinned Hawks, and two Merlins crossed the river and continued along the diabase ridge on the west shore, accessing a strong updraft along its slope to propel their journey further to the southwest. Four high-flying Bald Eagles migrated through, each following the east river shore downstream and making little use of the ridge except to gain a little altitude while passing by.

Late in the afternoon, the local Bald Eagles were again airborne and cackling up a storm. This time they intercepted an eagle coming down the ridge toward the river and immediately forced the bird to climb if it intended to pass. It turned out to be the best sighting of the day, and these “home team” eagles found it first. It was a Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) in crisp juvenile plumage. On its first southward voyage, it seemed to linger after climbing high enough for the Bald Eagles to loose concern, then finally selected the ridge route and crossed the river to head off to the southwest.

The humid rainy remains of Hurricane Nate have long since passed by Pennsylvania, yet mild wet weather lingers to confuse one’s sense of the seasons. This gloomy misty day was less than spectacular for watching migrating birds and insects, but some did pass by. Many resident animals of the falls are availing themselves of the opportunity to continue active behavior before the cold winds of autumn and winter force a change of lifestyle.

Warm drizzle at daybreak prompted several Northern Spring Peepers (Pseudacris crucifer crucifer) to begin calling from the wetlands in the Riparian Woodlands of Conewago Falls. An enormous chorus of these calls normally begins with the first warm rains of early spring to usher in this tiny frog’s mating season. Today, it was just a few “peeps” among anxious friends.

Any additional river flow that resulted from the rains of the previous week is scarcely noticeable among the Pothole Rocks. The water level remains low, the water column is fairly clear, and the water temperatures are in the 60s Fahrenheit.

It’s no real surprise then to see aquatic turtles climbing onto the boulders in the falls to enjoy a little warmth, if not from the sun, then from the stored heat in the rocks. As usual, they’re quick to slide into the depths soon after sensing someone approaching or moving nearby. Seldom found anywhere but on the river, these skilled divers are Common Map Turtles (Graptemys geographica), also known as Northern Map Turtles. Their paddle-like feet are well adapted to swimming in strong current. They are benthic feeders, feasting upon a wide variety of invertebrates found among the stone and substrate of the river bottom.

Adult Common Map Turtles hibernate communally on the river bottom in a location protected from ice scour and turbulent flow, often using boulders, logs, or other structures as shelter from strong current. The oxygenation of waters tumbling through Conewago Falls may be critical to the survival of the turtles overwintering downstream. Dissolved oxygen in the water is absorbed by the nearly inactive turtles as they remain submerged at their hideout through the winter. Though Common Map Turtles, particularly males, may occasionally move about in their hibernation location, they are not seen coming to the surface to breathe.

The Common Map Turtles in the Susquehanna River basin are a population disconnected from that found in the main range of the species in the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi basin. Another isolated population exists in the Delaware River.

SOURCES

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2002. Status Report of the Northern Map Turtle. Canadian Wildlife Service. Ottawa, Ontario.

A moderate breeze from the south placed a headwind into the face of migrants trying to wing their way to winter quarters. The urge to reach their destination overwhelmed any inclination a bird or insect may have had to stay put and try again another day.

Blue Jays were joined by increasing numbers of American Robins crossing the river in small groups to continue their migratory voyages. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and a handful of sandpipers headed down the river route. Other migrants today included a Cooper’s Hawk (Astur cooperii), Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis), and a few Common Mergansers (Mergus merganser), House Finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), and Common Grackles (Quiscalus quiscula).

The afternoon belonged to the insects. The warm wind blew scores of Monarchs toward the north as they persistently flapped on a southwest heading. Many may have actually lost ground today. Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) and Cloudless Sulphur butterflies were observed battling their way south as well. All three of the common migrating dragonflies were seen: Common Green Darner (Anax junius), Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens), and Black Saddlebags (Tramea lacerata).

The warm weather and summer breeze are expected to continue as the rain and wind from Hurricane Nate, today striking coastal Alabama and Mississippi, progresses toward the Susquehanna River watershed during the coming forty-eight hours.

A fresh breeze from the north brought cooler air and a reminder that summer is gone and autumn has arrived.

Fast-moving dark clouds provided a perfect backdrop for viewing passing diurnal migrants. Bald Eagles utilized the tail wind to cruise down the Susquehanna toward Chesapeake Bay and points further south. A migrating Merlin began a chase from which a Northern Flicker narrowly escaped by finding shelter among Pothole Rocks and a few small trees. The season’s first American Black Duck (Anas rubripes), Common Loon (Gavia immer), Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varia), and American Pipits (Anthus rubescens) moved through.

Blue Jays continued their hesitant crossings of the river at Conewago Falls. The majority completed the journey by forming groups of a dozen or more birds and following the lead of a lone American Robin, a Northern Flicker, or, odd as it appeared, a small warbler.

By far the most numerous migrants today were swallows. Thousands of Northern Rough-winged Swallows and hundreds of Tree Swallows were on the wing in search of what was suddenly a sparse flying insect supply. To get out of the brisk wind, some of the more resourceful birds landed on the warm rocks. To satisfy their appetite, many were able to pick crawling arthropods from the surface of the boulders. They swallow them whole.

The Neotropical birds that raised their young in Canada and in the northern United States have now logged many miles on their journey to warmer climates for the coming winter. As their density decreases among the masses of migrating birds, a shift to species with a tolerance for the cooler winter weather of the temperate regions will be evident.

Though it is unusually warm for this late in September, the movement of diurnal migrants continues. This morning at Conewago Falls, five Broad-winged Hawks (Buteo platypterus) lifted from the forested hills to the east, then crossed the river to continue a excursion to the southwest which will eventually lead them and thousands of others that passed through Pennsylvania this week to wintering habitat in South America. Broad-winged Hawks often gather in large migrating groups which swarm in the rising air of thermal updrafts, then, after gaining substantial altitude, glide away to continue their trip. These ever-growing assemblages from all over eastern North America funnel into coastal Texas where they make a turn to south around the Gulf of Mexico, then continue on toward the tropics. In the coming weeks, a migration count at Corpus Christi in Texas could tally 100,000 or more Broad-winged Hawks in a single day as a large portion of the continental population passes by. You can track their movement and that of other diurnal raptors as recorded at sites located all over North America by visiting hawkcount.org on the internet. Check it out. You’ll be glad you did.

Nearly all of the other migrants seen today have a much shorter flight ahead of them. Red-bellied Woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus), Red-headed Woodpeckers (Melanerpes erythrocephalus), and Northern Flickers (Colaptes auratus) were on the move. Migrating American Robins (Turdus migratorius) crossed the river early in the day, possibly leftovers from an overnight flight of this primarily nocturnal migrant. The season’s first Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) arrived. American Goldfinches are easily detected by their calls as they pass overhead. Look carefully at the goldfinches visiting your feeder, the birds of summer are probably gone and are being replaced by migrants currently passing through.

By far, the most conspicuous migrant today was the Blue Jay. Hundreds were seen as they filtered out of the hardwood forests of the diabase ridge to cautiously cross the river and continue to the southwest. Groups of five to fifty birds would noisily congregate in trees along the river’s edge, then begin flying across the falls. Many wary jays abandoned their small crossing parties and turned back. Soon, they would try the trip again in a larger flock.

A look at this morning’s count reveals few Neotropical migrants. With the exception of the Broad-winged Hawks and warblers, the migratory species seen today will winter in a sub-tropical temperate climate, primarily in the southern United States, but often as far north as the lower Susquehanna River valley. The individual birds observed today will mostly continue to a winter home a bit further south. Those that will winter in the area of Conewago Falls will arrive in October and later.

The long-distance migrating insect so beloved among butterfly enthusiasts shows signs of improving numbers. Today, more than two dozen Monarchs were seen crossing the falls and slowly flapping and gliding their way to Mexico.

A few nocturnal migrants flew through the moonlit night to arrive at Conewago Falls for a sunrise showing this morning. A dozen warblers were in the treetops and a Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) chattered away in the understory of the Riparian Woodlands. Three species of shorebirds were in the falls and on the Pothole Rocks: Least Sandpiper (Calidris minutilla), Lesser Yellowlegs (Tringa flavipes), and Greater Yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca).

The diurnal migration was highlighted by a Merlin (Falco columbarius), an Osprey, and a Bald Eagle, each flying down the river. Most of the other birds in the falls seemed content to linger and feed. There’s no need to hurry folks, only trouble lurks down there in paradise at the moment.

A couple of inches of rain this week caused a small increase in the flow of the river, just a burp, nothing major. This higher water coincided with some breezy days that kicked up some chop on the open waters of the Susquehanna upstream of Conewago Falls. Apparently it was just enough turbulence to uproot some aquatic plants and send them floating into the falls.

Piled against and upon the upstream side of many of the Pothole Rocks were thousands of two to three feet-long flat ribbon-like opaque green leaves of Tapegrass, also called Wild Celery, but better known as American Eelgrass (Vallisneria americana). Some leaves were still attached to a short set of clustered roots. It appears that most of the plants broke free from creeping rootstock along the edge of one of this species’ spreading masses which happened to thrive during the second half of the summer. You’ll recall that persistent high water through much of the growing season kept aquatic plants beneath a blanket of muddy current. The American Eelgrass colonies from which these specimens originated must have grown vigorously during the favorable conditions in the month of August. A few plants bore the long thread-like pistillate flower stems with a fruit cluster still intact. During the recent few weeks, there have been mats of American Eelgrass visible, the tops of their leaves floating on the shallow river surface, near the east and west shorelines of the Susquehanna where it begins its pass through the Gettysburg Basin near the Pennsylvania Turnpike bridge at Highspire. This location is a probable source of the plants found in the falls today.

The cool breeze from the north was a perfect fit for today’s migration count. Nocturnal migrants settling down for the day in the Riparian Woodlands at sunrise included more than a dozen warblers and some Gray Catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis). Diurnal migration was underway shortly thereafter.

Four Bald Eagles were counted as migrants this morning. Based on plumage, two were first-year eagles (Juvenile) seen up high and flying the river downstream, one was a second-year bird (Basic I) with a jagged-looking wing molt, and a third was probably a fourth year (Basic III) eagle looking much like an adult with the exception of a black terminal band on the tail. These birds were the only ones which could safely be differentiated from the seven or more Bald Eagles of varying ages found within the past few weeks to be lingering at Conewago Falls. There were as many as a dozen eagles which appeared to be moving through the falls area that may have been migrating, but the four counted were the only ones readily separable from the locals.

Red-tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) were observed riding the wind to journey not on a course following the river, but flying across it and riding the updraft on the York Haven Diabase ridge from northeast to southwest.

Bank Swallows (Riparia riparia) seem to have moved on. None were discovered among the swarms of other species today.

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Caspian Terns, Cedar Waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum), and Chimney Swifts (Chaetura pelagica) were migrating today, as were Monarch butterflies.

Not migrating, but always fun to have around, all four wise guys were here today. I’m referring to the four members of the Corvid family regularly found in the Mid-Atlantic states: Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata), American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), Fish Crow (Corvus ossifragus), and Common Raven (Corvus corax).

SOURCES

Klots, Elsie B. 1966. The New Field Book of Freshwater Life. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, NY.