Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

With large crowds of observers stopping by at the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area to view the thousands of migrating Snow Geese and Tundra Swans there, you may not notice the smaller but just as enthusiastic crowd gathering at the refuge to see a single, rather inconspicuous waterfowl, a male Tufted Duck (Aythya fuligula). This extraordinarily rare visitor has been on the refuge for at least two weeks now. The Tufted Duck, a diving benthic feeder, is native to Europe and Asia, but this vagrant individual seems to be comfortable in the company of its North American counterparts, a flock of Ring-necked Ducks. Birders known as “listers” relish the chance to see such an unusual find. Many are traveling from bordering states for a chance to add it to their list of species observed during their lifetime—their “life list”.

Want to start a “life list” of bird sightings? Just get out a piece of paper or start a document on your computer and jot down the name of the bird and the date and location where you saw it for the first time. That’s all there is to it. Beginning a “life list” can be the start of a lifelong passion. And a Tufted Duck wouldn’t be too shabby as the first “lifer” on your list.

It’s that time of year—Snow Geese on their northbound migration, more than 100,000 of them, have arrived for a stopover at the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties. Get there now to see scenes like these in person…

Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!

It’s surprising how many millions of people travel the busy coastal routes of Delaware each year to leave the traffic congestion and hectic life of the northeast corridor behind to visit congested hectic shore towns like Rehobeth Beach, Bethany Beach, and Ocean City, Maryland. They call it a vacation, or a holiday, or a weekend, and it’s exhausting. What’s amazing is how many of them drive right by a breathtaking national treasure located along Delaware Bay just east of the city of Dover—and never know it. A short detour on your route will take you there. It’s Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, a quiet but spectacular place that draws few crowds of tourists, but lots of birds and other wildlife.

Let’s join Uncle Tyler Dyer and have a look around Bombay Hook. He’s got his duck stamp and he’s ready to go.

Remember to go the Post Office and get your duck stamp. You’ll be supporting habitat acquisition and improvements for the wildlife we cherish. And if you get the chance, visit a National Wildlife Refuge. November can be a great time to go, it’s bug-free! Just take along your warmest clothing and plan to spend the day. You won’t regret it.

Late August and early September is prime time to see migrating shorebirds as they pass through the lower Susquehanna valley during their autumn migration, which, believe it or not, can begin as early as late June. These species that are often assumed to spend their lives only near the seashore are regular visitors each fall as they make their way from breeding grounds in the interior of Canada to wintering sites in seacoast wetlands—many traveling as far south as Central and South America.

Low water levels on the Susquehanna River often coincide with the shorebird migration each year, exposing gravel and sand bars as well as vast expanses of muddy shorelines as feeding and resting areas for these traveling birds. This week though, rain from the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred arrived to increase the flow in the Susquehanna and inundate most of the natural habitat for shorebirds. Those on the move must either continue through the area without stopping or find alternate locations to loaf and find food.

The draining and filling of wetlands along the river and elsewhere in the region has left few naturally-occurring options. The Conejohela Flats south of Columbia offer refuge to many migrating sandpipers and their allies, the river level there being controlled by releases from the Safe Harbor Dam during all but the severest of floods. Shorebirds will sometimes visit flooded fields, but wide-open puddles and farmland resembling mudflats is more of springtime occurrence—preceding the planting and growth of crops. Well-designed stormwater holding facilities can function as habitat for sandpipers and other wildlife. They are worth checking on a regular basis—you never know what might drop in.

Right now, there is a new shorebird hot spot in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed—Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area. The water level in the main impoundment there has been drawn down during recent weeks to expose mudflats along the periphery of nearly the entire lake. Viewing from “Stop 1” (the roadside section of the lake in front of the refuge museum) is best. The variety of species and their numbers can change throughout the day as birds filter in and out—at times traveling to other mudflats around the lake where they are hidden from view. The birds at “Stop 1” are backlit in the morning with favorable illumination developing in the afternoon.

Have a look at a few of the shorebirds currently being seen at Middle Creek…

The aquatic environs at Middle Creek attract other species as well. Here are some of the most photogenic…

Except for a few injured stragglers, Snow Geese have departed Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties to continue their journey north to breeding grounds in Canada. The crowds of observers are gone too. So if you’re looking for a reason to pay a visit to a much quieter refuge, here it is—especially if you’re a devoted deer worshiper.

There is at least one white deer being seen on the refuge. That’s right, a white deer. Its unusual color is really becoming conspicuous as the landscape begins turning from shades of gray to various hues of bright green.

If you go, you’ll need binoculars to pick out these uncommon deer. And remember to be very careful when parking and observing along Kleinfeltersville Road. The speeding cars and trucks there can be wickedly dangerous, so give them lots of room.

It’s that time—Snow Goose numbers are peaking at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster/Lebanon Counties.

Spring migration is underway and waterfowl are on the move along the lower Susquehanna River. Here is a sample of sightings collected during a walk across the Veteran’s Memorial Bridge at Columbia-Wrightsville this morning.

This is, of course, just the beginning of the great spring migration. Do make a point of getting out to observe the spectacle. And remember, keep looking up—you wouldn’t want to miss anything.

With plenty of open water on the main lake and no snow cover on the fields where they graze, Snow Geese have begun arriving at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area in Lancaster/Lebanon Counties. As long as our mild winter weather continues, more can be expected to begin moving inland from coastal areas to prepare for their spring migration and a return to arctic breeding grounds.

You probably need a break from being indoors all month, so why not get out and have a look?

Don’t just sit there—don your coat, grab a pair of binoculars, and get out and have a gander!

You say you really don’t want to take a look back at 2020? Okay, we understand. But here’s something you may find interesting, and it has to do with the Susquehanna River in 2020.

As you may know, the National Weather Service has calculated the mean temperature for the year 2020 as monitored just upriver from Conewago Falls at Harrisburg International Airport. The 56.7° Fahrenheit value was the highest in nearly 130 years of monitoring at the various stations used to register official climate statistics for the capital city. The previous high, 56.6°, was set in 1998.

Though not a prerequisite for its occurrence, record-breaking heat was accompanied by a drought in 2020. Most of the Susquehanna River drainage basin experienced drought conditions during the second half of the year, particularly areas of the watershed upstream of Conewago Falls. A lack of significant rainfall resulted in low river flows throughout late summer and much of the autumn. Lacking water from the northern reaches, we see mid-river rocks and experience minimal readings on flow gauges along the lower Susquehanna, even if our local precipitation happens to be about average.

Back in October, when the river was about as low as it was going to get, we took a walk across the Susquehanna at Columbia-Wrightsville atop the Route 462/Veteran’s Memorial Bridge to have a look at the benthos—the life on the river’s bottom.

These improvements in water quality and wildlife habitat can have a ripple effect. In 2020, the reduction in nutrient loads entering Chesapeake Bay from the low-flowing Susquehanna may have combined with better-than-average flows from some of the bay’s lesser-polluted smaller tributaries to yield a reduction in the size of the bay’s oxygen-deprived “dead zones”. These dead zones typically occur in late summer when water temperatures are at their warmest, dissolved oxygen levels are at their lowest, and nutrient-fed algal blooms have peaked and died. Algal blooms can self-enhance their severity by clouding water, which blocks sunlight from reaching submerged aquatic plants and stunts their growth—making quantities of unconsumed nutrients available to make more algae. When a huge biomass of algae dies in a susceptible part of the bay, its decay can consume enough of the remaining dissolved oxygen to kill aquatic organisms and create a “dead zone”. The Chesapeake Bay Program reports that the average size of this year’s dead zone was 1.0 cubic miles, just below the 35-year average of 1.2 cubic miles.

Back on a stormy day in mid-November, 2020, we took a look at the tidal freshwater section of Chesapeake Bay, the area known as Susquehanna Flats, located just to the southwest of the river’s mouth at Havre de Grace, Maryland. We wanted to see how the restored American Eelgrass beds there might have fared during a growing season with below average loads of nutrients and life-choking sediments spilling out of the nearby Susquehanna River. Here’s what we saw.

We noticed a few Canvasbacks (Aythya valisineria) on the Susquehanna Flats during our visit. Canvasbacks are renowned as benthic feeders, preferring the tubers and other parts of submerged aquatic plants (a.k.a. submersed aquatic vegetation or S.A.V.) including eelgrass, but also feeding on invertebrates including bivalves. The association between Canvasbacks and eelgrass is reflected in the former’s scientific species name valisineria, a derivitive of the genus name of the latter, Vallisneria.

The plight of the Canvasback and of American Eelgrass on the Susquehanna River was described by Herbert H. Beck in his account of the birds found in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, published in 1924:

“Like all ducks, however, it stops to feed within the county less frequently than formerly, principally because the vast beds of wild celery which existed earlier on broads of the Susquehanna, as at Marietta and Washington Borough, have now been almost entirely wiped out by sedimentation of culm (anthracite coal waste). Prior to 1875 the four or five square miles of quiet water off Marietta were often as abundantly spread with wild fowl as the Susquehanna Flats are now.”

Beck quotes old Marietta resident and gunner Henry Zink:

“Sometimes there were as many as 500,000 ducks of various kinds on the Marietta broad at one time.”

The abundance of Canvasbacks and other ducks on the Susquehanna Flats would eventually plummet too. In the 1950s, there were an estimated 250, 000 Canvasbacks wintering on Chesapeake Bay, primarily in the area of the American Eelgrass, a.k.a. Wild Celery, beds on the Susquehanna Flats. When those eelgrass beds started disappearing during the second half of the twentieth century, the numbers of Canvasbacks wintering on the bay took a nosedive. As a population, the birds moved elsewhere to feed on different sources of food, often in saltier estuarine waters.

Canvasbacks were able to eat other foods and change their winter range to adapt to the loss of habitat on the Susquehanna River and Chesapeake Bay. But not all species are the omnivores that Canvasbacks happen to be, so they can’t just change their diet and/or fly away to a better place. And every time a habitat like the American Eelgrass plant community is eliminated from a region, it fragments the range for each species that relied upon it for all or part of its life cycle. Wildlife species get compacted into smaller and smaller suitable spaces and eventually their abundance and diversity are impacted. We sometimes marvel at large concentrations of birds and other wildlife without seeing the whole picture—that man has compressed them into ever-shrinking pieces of habitat that are but a fraction of the widespread environs they once utilized for survival. Then we sometimes harass and persecute them on the little pieces of refuge that remain. It’s not very nice, is it?

By the end of 2020, things on the Susquehanna were getting back to normal. Near normal rainfall over much of the watershed during the final three months of the year was supplemented by a mid-December snowstorm, then heavy downpours on Christmas Eve melted it all away. Several days later, the Susquehanna River was bank full and dishing out some minor flooding for the first time since early May. Isn’t it great to get back to normal?

SOURCES

Beck, Herbert H. 1924. A Chapter on the Ornithology of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The Lewis Historical Publishing Company. New York, NY.

White, Christopher P. 1989. Chesapeake Bay, Nature of the Estuary: A Field Guide. Tidewater Publishers. Centreville, MD.

So you aren’t particularly interested in a stroll through the Pennsylvania woods during the gasoline and gunpowder gang’s second-biggest holiday of the year—the annual sacrifice-of-the-White-tailed-Deity ritual. I get it. Two weeks and nothing to do. Well, why not try a hike through the city instead? I’m not kidding. You might be surprised at what you see. Here are some photographs taken today during several strolls in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

First stop was City Island in the Susquehanna River—accessible from downtown Harrisburg or the river’s west shore by way of the Market Street Bridge.

Okay, City Island was worth the effort. Next stop is Wildwood Park, located along Industrial Road just north of the Pennsylvania Farm Show complex and the Harrisburg Area Community College (HACC) campus. There are six miles of trails surrounding mile-long Wildwood Lake within this marvelous Dauphin County Parks Department property.

And now, without further ado, it’s time for the waterfowl of Wildwood Lake—in order of their occurrence.

See, you don’t have to cloak yourself in bright orange ceremonial garments just to go for a hike. Go put on your walking shoes and a warm coat, grab your binoculars and/or camera, and have a look at wildlife in a city near you. You never know what you might find.

SOURCES

Taylor, Scott A., Thomas A. White, Wesley M. Hochachka, Valentina Ferretti, Robert L. Curry, and Irby Lovette. 2014. “Climate-Mediated Movement of an Avian Hybrid Zone”. Current Biology. 24:6 pp.671-676.

The southbound bird migration of 2020 is well underway. With passage of a cold front coming within the next 48 hours, the days ahead should provide an abundance of viewing opportunities.

Here are some of the species moving through the lower Susquehanna valley right now.

Some of the newest mothers in the lower Susquehanna valley—nurturing their young.

And a soon-to-be mother making the necessary preparations to bring a new generation into the world.

Have a Happy Mother’s Day!

For those of you who dare to shed that filthy contaminated rag you’ve been told to breathe through so that you might instead get out and enjoy some clean air in a cherished place of solitude, here’s what’s around—go have a look.

The springtime show on the water continues…

Hey, what are those showy flowers?

Wasn’t that refreshing? Now go take a walk.

Fog and mist lingered throughout the day, as did the migratory water birds on the river and lakes in the lower Susquehanna valley. As a continuation of yesterday’s post on the fallout, here’s a photo tour of some of the sites where ducks, loons, grebes, and other birds have gathered.

Stormy weather certainly is a birder’s delight.

Local birders enjoy going to the Atlantic coast of New Jersey and Delmarva in the winter. The towns and beaches host far fewer people than birds, and many of the species seen are unlikely to be found anywhere else in the region. Unusual rarities add to the excitement.

The regular seaside attraction in winter is the variety of diving ducks and similar water birds that feed in the ocean surf and in the saltwater bays. Most of these birds breed in Canada and many stealthily cross over the landmass of the northeastern United States during their migrations. If an inland birder wants to see these coastal specialties, a trip to the shore in winter or a much longer journey to Canada in the summer is normally necessary—unless there is a fallout.

Migrating birds can show up in strange places when a storm interrupts their flight. Forest songbirds like thrushes and warblers frequently take temporary refuge in a wooded backyard or even in a city park when forced down by inclement weather. Loons have been found in shopping center parking lots after mistaking the wet asphalt for a lake. Fortunately though, loons, ducks, and other water birds usually find suitable ponds, lakes, and rivers as places of refuge when forced down. For inland birders, a fallout like this can provide an opportunity to observe these coastal species close to home.

Not so coincidentally, it has rained throughout much of today in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, apparently interrupting a large movement of migrating birds. There is, at the time of this writing, a significant fallout of coastal water birds here. Hundreds of diving ducks and other benthic feeders are on the Susquehanna River and on some of the clearer lakes and ponds in the region. They can be expected to remain until the storm passes and visibility improves—then they’ll promptly commence their exodus.

The following photographs were taken during today’s late afternoon thundershower at Memorial Lake State Park at Fort Indiantown Gap, Lebanon County.

Migrating land birds have also been forced down by the persistent rains.

Why not get out and take a slow quiet walk on a rainy day. It may be the best time of all for viewing certain birds and other wildlife.

The mild winter has apparently minimized weather-related mortality for the local Green Frog population. With temperatures in the seventies throughout the lower Susquehanna valley for this first full day of spring, many recently emerged adults could be seen and, on occasion, heard. Yellow-throated males tested their mating calls—reminding the listener of the sound made by the plucking of a loose banjo string.

If you venture out, keep alert for the migrating birds of late winter and early spring.

If you’re staying close to home, be sure to check out the changing appearance of the birds you see nearby. Some species are losing their drab winter basic plumage and attaining a more colorful summer breeding alternate plumage.

So just how many Green Frogs were there in that first photograph? Here’s the answer.

Happy Spring. For the benefit of everyone’s health, let’s hope that it’s a hot and humid one!

According to the most recent Pennsylvania Game Commission estimate, there are presently more than 100,000 Snow Geese at the Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area (W.M.A.) in Lancaster and Lebanon Counties. It’s a spectacular sight.

If you go to see these and other birds at Middle Creek, it’s important to remember that you are visiting them in a “wildlife refuge” set aside for, believe it or not, wildlife. “Wildlife refuge”, many would be surprised to learn, is short for “terrestrial or aquatic habitat where wildlife can find refuge and protection from all the meddlesome and murderous things people do”.

Nothing says Happy Valentine’s Day like a really bad poem, so here it is…

FOR THE LOVE OF DUCKS

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

My neighbors are complainin’

I can hear them talk

The mallards eat their garden

Let surprises on their walk

Dung stains on the carpets

They tracked it in the house

It’s from those ducks and not the pets

Can’t blame it on the spouse

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

Tamed with bread and crackers

I gave them as a treat

I soon found maimed dead quackers

Lying in the street

A driver who intended

To miss the hens and drakes

Had their car rear-ended

When they hit the brakes

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

The flock is very wasteful

Each bird a pound a day

Web-foots in a cesspool

Pollute the waterway

There are some kids playing

In that filthy ditch

Soon they’ll be displaying

The rash of Swimmer’s Itch

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

These ducks they do not migrate

They’re here day in, day out

Aquatic life they decimate

No plants, no fish, no trout

Hurry! Hurry! Heed my call

Before it starts to rain

Ten more ducklings took a fall

And are stranded in a drain

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

Have you people lost your minds?

I see you by your fence

These ducks are cute and I am kind

It’s you who’ve lost your sense

Beggars from the handouts

My God what have I done?

Their senseless habits leave no doubt

Their instincts are all gone

I like to feed the duckies

Try it and you’ll see

Aren’t they really lucky?

Relying just on me

Now I know just what to do

Like one would teach a child

I’ll feed the ducks at the zoo

And let the rest live wild

So if you feed the duckies

Beware of the spell

Or you will do the same as me

Loving ducks to death as well

—Ducks Anonymous, LLC

Inside the doorway that leads to your editor’s 3,500 square foot garden hangs a small chalkboard upon which he records the common names of the species of birds that are seen there—or from there—during the year. If he remembers to, he records the date when the species was first seen during that particular year. On New Year’s Day, the results from the freshly ended year are transcribed onto a sheet of notebook paper. On the reverse, the names of butterflies, mammals, and other animals that visited the garden are copied from a second chalkboard that hangs nearby. The piece of paper is then inserted into a folder to join those from previous New Year’s Days. The folder then gets placed back into the editor’s desk drawer beneath a circular saw blade and an old scratched up set of sunglasses—so that he knows exactly where to find it if he wishes to.

A quick glance at this year’s list calls to mind a few recollections.

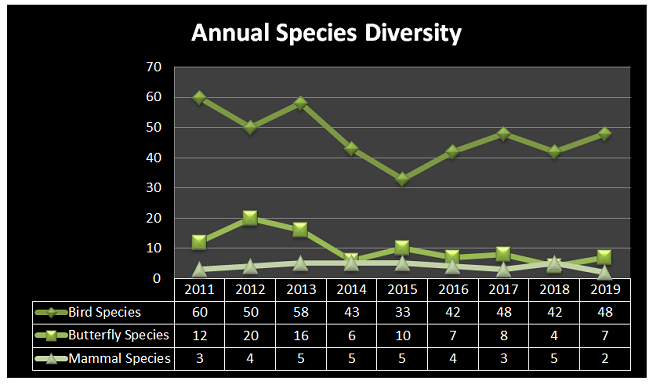

Before putting the folder back into the drawer for another year, the editor decided to count up the species totals on each of the sheets and load them into the chart maker in the computer.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

It appears that, at the very least, the garden habitat has been disconnected from the home ranges of many species by fragmentation. His little oasis is now isolated in a landscape that becomes increasingly hostile to native wildlife with each passing year. The paving of more parking areas, the elimination of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous growth from the large number of rental properties in the area, the alteration of the biology of the nearby stream by hand-fed domestic ducks, light pollution, and the outdoor use of pesticides have all contributed to the separation of the editor’s tiny sanctuary from the travel lanes and core habitats of many of the species that formerly visited, fed, or bred there. In 2019, migrants, particularly “fly-overs”, were nearly the only sightings aside from several woodpeckers, invasive House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and hardy Mourning Doves. Even rascally European Starlings became sporadic in occurrence—imagine that! It was the most lackluster year in memory.

If habitat fragmentation were the sole cause for the downward trend in numbers and species, it would be disappointing, but comprehensible. There would be no cause for greater alarm. It would be a matter of cause and effect. But the problem is more widespread.

Although the editor spent a great deal of time in the garden this year, he was also out and about, traveling hundreds of miles per week through lands on both the east and the west shores of the lower Susquehanna. And on each journey, the number of birds seen could be counted on fingers and toes. A decade earlier, there were thousands of birds in these same locations, particularly during the late summer.

In the lower Susquehanna valley, something has drastically reduced the population of birds during breeding season, post-breeding dispersal, and the staging period preceding autumn migration. In much of the region, their late-spring through summer absence was, in 2019, conspicuous. What happened to the tens of thousands of swallows that used to gather on wires along rural roads in August and September before moving south? The groups of dozens of Eastern Kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus) that did their fly-catching from perches in willows alongside meadows and shorelines—where are they?

Several studies published during the autumn of 2019 have documented and/or predicted losses in bird populations in the eastern half of the United States and elsewhere. These studies looked at data samples collected during recent decades to either arrive at conclusions or project future trends. They cite climate change, the feline infestation, and habitat loss/degradation among the factors contributing to alterations in range, migration, and overall numbers.

There’s not much need for analysis to determine if bird numbers have plummeted in certain Lower Susquehanna Watershed habitats during the aforementioned seasons—the birds are gone. None of these studies documented or forecast such an abrupt decline. Is there a mysterious cause for the loss of the valley’s birds? Did they die off? Is there a disease or chemical killing them or inhibiting their reproduction? Is it global warming? Is it Three Mile Island? Is it plastic straws, wind turbines, or vehicle traffic?

The answer might not be so cryptic. It might be right before our eyes. And we’ll explore it during 2020.

In the meantime, Uncle Ty and I going to the Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg. You should go too. They have lots of food there.

There was a hint of what was to come. If you were out and about before dawn this morning, you may have been lucky enough to hear them passing by high overhead. It was 5:30 A.M. when I opened the door and was greeted by that distinctive nasal whistle. Stepping through the threshold and into the cold, I peered into the starry sky and saw them, their feathers glowing orange in the diffused light from the streets and parking lots below. Their size and snow-white plumage make Tundra Swans one of the few species of migrating birds you’ll ever get to visibly discern in a dark moonless nighttime sky.

The calm air at daybreak and through the morning transitioned to a steady breeze from the south in the afternoon. Could this be it? Would this be that one day in late February or the first half of March each year when waterfowl (and other birds too) seem to take advantage of the favorable wind to initiate an “exodus” and move in conspicuous numbers up the lower Susquehanna valley on their way to breeding grounds in the north? Well, indeed it would be. And with the wind speeding up the parade, an observer at a fixed point on the ground gets to see more birds fly by.

In the late afternoon, an observation location in the Gettysburg Basin about five miles east of Conewago Falls in Lancaster County seemed to be well-aligned with a northwesterly flight path for migrating Tundra Swans. At about 5:30 P.M., the clear sky began clouding over, possibly pushing high-flying birds more readily into view. During the next several hours, over three thousand Tundra Swans passed overhead, flocks continuing to pass for a short time after nightfall. There were more than one thousand Canada Geese, the most numerous species on similar days in previous years. Sometimes on such a day there are numerous ducks. Not today. The timing, location, and conditions put Tundra Swans in the spotlight for this year’s show.

Other migrants moving concurrently with the waterfowl included Ring-billed Gulls, American Herring Gulls (6+), American Robins (50+), Red-winged Blackbirds (500+), and Common Grackles (100+).

Though I’ve only seen such a spectacle only once during a season in recent years, there certainly could be another large flight of ducks, geese, or swans yet to come. The breeze is forecast to continue from southerly directions for at least another day. Keep you eyes skyward, no matter where you might happen to be in the lower Susquehanna valley. These or other migratory species may put on another show, a “big day”, just for you.

One can get a stiff neck looking up at the flurry of bird activity in the treetops at this time of year. Many of the Neotropical migrants favor rich forests as daytime resting sites after flying through the night. For others, these forests are a destination where they will nest and raise their young.

For the birds that arrive earlier in spring than the Neotropical migrants, the breeding season is well underway. The wet weather may be impacting the success of the early nests.

So long for now, if you’ll excuse me please, I have a sore neck to tend to.

You remember the signs of an early spring, don’t you? It was a mild, almost balmy, February. The earliest of the spring migrants such as robins and blackbirds were moving north through the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. The snow had melted and ice on the river had passed. Everyone was outdoors once again. At last, winter was over and only the warmer months lie ahead…beginning with March.

Ah yes, March, the cold windy month of March. We remember February fondly, but this March has startled us out of our vernal daydreams to wrestle with the reality of the season. And if you’re anywhere near the Mid-Atlantic states on this first full day of spring, you know that a long winter’s nap and visions of sugar peas would be time better spent than a stroll outdoors. Presently it’s dusk, and the snow from the 4th “Nor’easter” in a month is a foot deep and still falling.

In honor of “The Spring That Was”, here then is a sampling of some of the migratory waterfowl that have found their way to the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed during March. Some are probably lingering and feeding for a while. All will move along to their breeding grounds within a couple of weeks, regardless of the weather.

At the moment there is a heavy snow falling, not an unusual occurrence for mid-February, nevertheless, it is a change in weather. Forty-eight hours ago we were in the midst of a steady rain and temperatures were in the sixties. The snow and ice had melted away and a touch of spring was in the air.

Anyone casually looking about while outdoors during these last several days may have noticed that birds are indeed beginning to migrate north in the lower Susquehanna valley. Killdeer, American Robins, Eastern Bluebirds, Red-winged Blackbirds, and Common Grackles are easily seen or heard in most of the area now.

Just hours ago, between nine o’clock this morning and one o’clock this afternoon, there was a spectacular flight of birds following the river north, their spring migration well underway. In the blue skies above Conewago Falls, a steady parade of Ring-billed Gulls was utilizing thermals and riding a tailwind from the south-southeast to cruise high overhead on a course toward their breeding range.

The swirling hoards of Ring-billed Gulls attracted other migrants to take advantage of the thermals and glide paths on the breeze. Right among them were 44 American Herring Gulls, 3 Great Black-backed Gulls, 12 Tundra Swans (Cygnus columbianus), 10 Canada Geese, 3 Northern Pintails (Anas acuta), 6 Common Mergansers, 3 Red-tailed Hawks, a Red-shouldered Hawk, 6 Bald Eagles (non-adults), 8 Black Vultures, and 5 Turkey Vultures.

In the afternoon, the clouds closed in quickly, the flight ended, and by dusk more than an inch of snow was on the ground. Looks like spring to me.

A steady stream of birds was on the move this morning over Conewago Falls. There were hundreds of Ring-billed Gulls, scores of American Herring Gulls, and a few Great Black-backed Gulls to dominate the flight. Then too there were thirteen Mallards, Turkey Vultures and a Black Vulture, twenty or more American Robins, a half a dozen Bald Eagles (juvenile and immature birds), a couple of Red-winged Blackbirds, and, perhaps most unusual of all, a flock of a dozen Scoters (Melanitta species), a waterfowl typical of the Mid-Atlantic surf in winter. All of these birds were diligently following the river, and into a headwind no less.

“Hold on just a minute there, buster,” you may say, “I’ve looked at the migration count by dutifully clicking on the logo above and there is nothing but zeroes on the count sheet for today. The season totals have not changed since the previous count day!”

Ah-ha, my dedicated friend, correct you are. It seems that today’s bird flight was solely in one direction. And that direction was upriver, moving north into a north breeze, on a heading which conflicts with all logic for creatures that should still be headed south for winter. As a result, none of the birds observed today were counted on the “Autumn Migration Count”.

You might say, “Don’t you know that Winter Solstice was three days ago, so autumn and autumn migration is over.”

Okay, point well taken. I should therefore clarify that what we title as “Autumn Migration Count” is more accurately a census of birds, insects, and other creatures transiting from northerly latitudes to more favorable latitudes to the south for winter. This transit can begin as early as late June and extend into the first weeks of winter. While most of this movement is motivated by the reduced hours of daylight during the period, late season migrants are often responding to ice, bad weather, or lack of food to prompt a journey further south. Migration south in late December and January occurs even while the amount of daylight is increasing slightly in the days following the Winter Solstice.

So what of the birds seen flying north today? There was some snow cover that has melted away, and the ice that formed on the river a week ago is gone due to the milder than normal temperatures this week.

One may ask, “Were the birds seen today migrating north?”

Let’s look at the species seen moving upriver today a try to determine their motivation.

First, and perhaps most straight-forward, is the huge flight of gulls. Wintering gulls on the Susquehanna River near Conewago Falls tend to spend their nights in flocks on the water or on treeless islands and rocky outcrops in the river. Many hundreds, sometimes thousands, find such favorable sites along the fifteen mile stretch of river from Conewago Falls downstream to Lake Clarke and the Conejohela Flats at Washington Boro. Each morning most of these gulls venture out to suburbia, farmland, landfill, hydroelectric dams, and other sections of river in search of food. Gulls are very able fliers and easily cover dozens of miles outbound and inbound each day in search of food. Many of the gulls seen this morning were probably on their way to the Harrisburg metropolitan area to eat trash. Barring any extraordinary buildups of ice on this section of river, one would expect these gulls to remain and make these daily excursions to food sources through early spring.

Second, throughout the season Bald Eagles have been tallied on the migration count with caution. Flight altitude, behavior, plumage, and the reaction of the “local” eagles to these transients was carefully considered before counting an eagle as a migrant. They roam a lot, particularly when young, and range widely to feed. The movement of eagles up the river today was probably food related. A gathering of adult, juvenile, and immature Bald Eagles could be seen more than a half mile upstream from the migration count lookout. Those moving up the river seemed to assemble with the “locals” there throughout the morning. White-tailed Deities occasionally drown, particularly when there is thin or unstable ice on the river (as there was last week) and they attempt to tread upon it. Then, their bodies are often stranded among rocks, in trees, or on the crown of the dam. After such a mishap, their carcasses become meals for carrion-eaters in the falls. Such an unfortunate deity, or another source of food, may have been attracting the eagles in numbers today.

Next, Black and Turkey Vultures often roam widely in search of food. The small numbers seen headed up-river today would tend to mean very little when trying to determine if there is a trend or population shift. Again, food may have been luring them upriver from nearby roosts.

And finally, the scoters, Mallards, American Robins, and Red-winged Blackbirds may have been wandering as well. Toward mid-day, the wind speed picked up and the direction changed to the east. This raises the possibility that these and others of the birds seen today may sense a change in weather, and may seek to take flight from the inclement conditions. Prompted by the ocean breeze and in an attempt to avoid a storm, was there some movement away from the Atlantic Coastal Plain to the upper Piedmont today? Many species may make these types of reactive movements. Is it possible that some birds flee or avoid ever-changing storm tracks and alter there wintering locations based on jet streams, water currents, and other climatic conditions? Probably. These are interesting dynamics and something worthy of study outside the simpler methods of a migration count.

…And if it snows that stretch down south won’t ever stand the strain… —Jimmy Webb

The lower Susquehanna valley’s first snowfall of the season arrived yesterday. By this morning it measured just an inch in depth at Conewago Falls, more to the south and east, less to the west and north. By mid-morning a cold fresh to moderate breeze from the northwest was blowing through the falls and stirring up ripples on the river.

Gulls sailed high overhead on the wind, taking a speedy ride downriver toward Chesapeake Bay, the Atlantic coast, and countless fast-food restaurant parking lots where surviving winter weather is more of a sure thing. Nearly a thousand Ring-billed Gulls soared past the migration count lookout today. Thirteen American Herring Gulls and four Great Black-backed Gulls were among them.

Other migrants today included a Mallard, twenty-nine American Black Ducks, two Bald Eagles, eleven Black Vultures, fifteen Turkey Vultures, five American Goldfinches, and fifteen Red-winged Blackbirds. The wintry weather seems to be prompting these late-season travelers to be on their way.

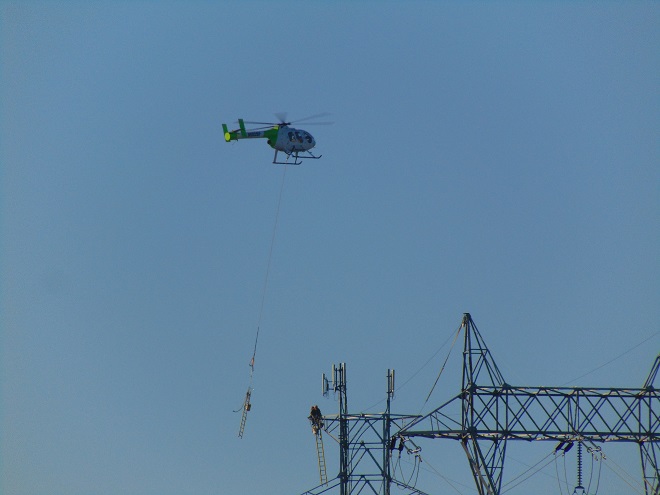

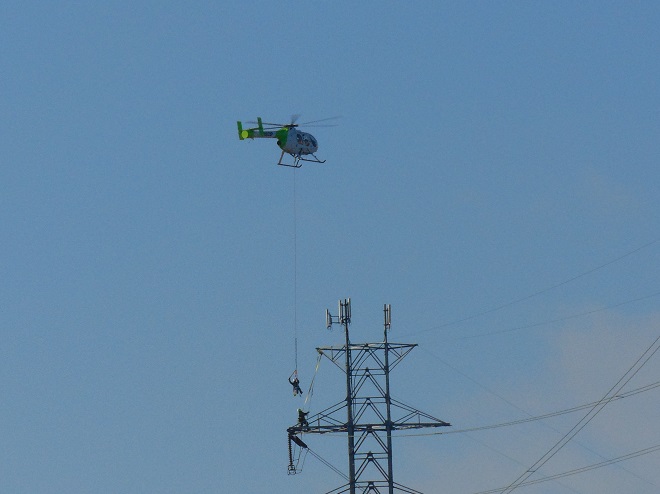

You know, today was like many other days at the falls. As I arrive, I have the habit of checking all the power line towers on both river shorelines to see what may be there awaiting discovery. More often than not, something interesting is perched on one or more of the structures…

Yes friends, while the birds migrated through high above, down below a coordinated effort was underway to replace some of the electric transmission cable that stretches across the Susquehanna River at Conewago Falls. As you’ll see, this project requires precise planning, preparation, and skill. And it was fascinating to watch!

It was a crisp clear morning with birdless blue skies. The migration has mostly drawn to a close; very little was seen despite a suitable northwest breeze to support a flight. There were no robins and no blackbirds. Not even a starling was seen today. The only highlights were a Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) and a couple of Swamp Sparrows.

And now ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, it’s time for a Thanksgiving Day culinary reminder from the local Conewago Falls Turkey…

The NOAA National Weather Service radar images from last evening provided an indication that there may be a good fallout of birds at daybreak in the lower Susquehanna valley. The moon was bright, nearly full, and there was a gentle breeze from the north to move the nocturnal migrants along. The conditions were ideal.

The Riparian Woodlands at Conewago Falls were alive with migrants this morning. American Robins and White-throated Sparrows were joined by new arrivals for the season: Brown Creeper (Certhia americana), Ruby-crowned Kinglets (Regulus calendula), Golden-crowned Kinglets (Regulus satrapa), Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis), and Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata). These are the perching birds one would expect to have comprised the overnight flight. While the individuals that will remain may not yet be among them, these are the species we will see wintering in the Mid-Atlantic states. No trip to the tropics for these hardy passerines.

It was a placid morning on Conewago Falls with blue skies dotted every now and then by a small flock of migrating robins or blackbirds. The jumbled notes of a singing Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis) in the Riparian Woodland softly mixed with the sounds of water spilling over the dam. The season’s first Wood Ducks (Aix sponsa), Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors), American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus), Horned Larks (Eremophila alpestris), and White-throated Sparrows (Zonotrichia albicollis) were seen.

There was a small ruckus when one of the adult Bald Eagles from a local pair spotted an Osprey passing through carrying a fish. This eagle’s effort to steal the Osprey’s catch was soon interrupted when an adult eagle from a second pair that has been lingering in the area joined the pursuit. Two eagles are certainly better than one when it’s time to hustle a skinny little Osprey, don’t you think?

But you see, this just won’t do. It’s a breach of eagle etiquette, don’t you know? Soon both pairs of adult eagles were engaged in a noisy dogfight. It was fussing and cackling and the four eagles going in every direction overhead. Things calmed down after about five minutes, then a staring match commenced on the crest of the dam with the two pairs of eagles, the “home team” and the “visiting team”, perched about 100 feet from each other. Soon the pair which seems to be visiting gave up and moved out of the falls for the remainder of the day. The Osprey, in the meantime, was able to slip away.

In recent weeks, the “home team” pair of Bald Eagles, seen regularly defending territory at Conewago Falls, has been hanging sticks and branched tree limbs on the cross members of the power line tower where they often perch. They seem only to collect and display these would-be nest materials when the “visiting team” pair is perched in the nearby tower just several hundred yards away…an attempt to intimidate by homesteading. It appears that with winter and breeding time approaching, territorial behavior is on the increase.

In the afternoon, a fresh breeze from the south sent ripples across the waters among the Pothole Rocks. The updraft on the south face of the diabase ridge on the east shore was like a highway for some migrating hawks, falcons, and vultures. Black Vultures (Coragyps atratus) and Turkey Vultures streamed off to the south headlong into the wind after leaving the ridge and crossing the river. A male and female Northern Harrier (Circus hudsonius), ten Red-tailed Hawks, two Red-shouldered Hawks (Buteo lineatus), six Sharp-shinned Hawks, and two Merlins crossed the river and continued along the diabase ridge on the west shore, accessing a strong updraft along its slope to propel their journey further to the southwest. Four high-flying Bald Eagles migrated through, each following the east river shore downstream and making little use of the ridge except to gain a little altitude while passing by.

Late in the afternoon, the local Bald Eagles were again airborne and cackling up a storm. This time they intercepted an eagle coming down the ridge toward the river and immediately forced the bird to climb if it intended to pass. It turned out to be the best sighting of the day, and these “home team” eagles found it first. It was a Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) in crisp juvenile plumage. On its first southward voyage, it seemed to linger after climbing high enough for the Bald Eagles to loose concern, then finally selected the ridge route and crossed the river to head off to the southwest.