As we begin the second half of October, frosty nights have put an end to choruses of annual cicadas in the lower Susquehanna valley. Though they are gone for yet another year, they are not forgotten. Here’s an update on one of our special finds in 2025.

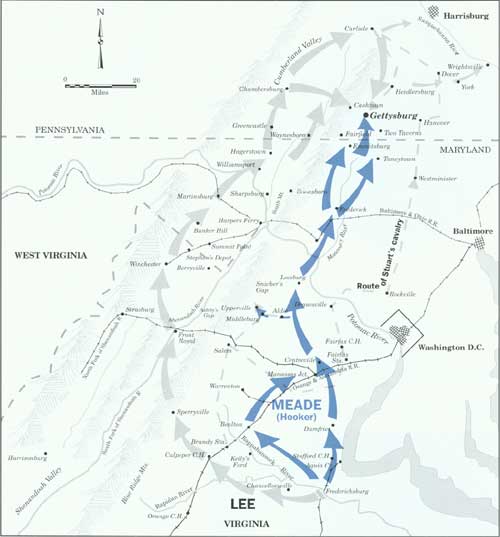

During late June of 1863, the beginning of the third summer of the American Civil War, there was great consternation among the populous of the lower Susquehanna region. Hoping to bring about Union capitulation and an end to the conflict, General Robert E. Lee and his 70,000-man Army of Northern Virginia were marching north into the passes and valleys on the west side of the river. The uncontested Confederate advances posed an immediate threat to Pennsylvania’s capital in Harrisburg and cities to the east. Marching north in pursuit of Lee was the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac, the lead element of the 100,000-man Union force under the direction of newly appointed commander General George G. Meade.

Upon belatedly learning of Meade’s pursuit, Lee hastily ordered the widely separated corps of his army to concentrate on the crossroads town of Gettysburg. As the southern army’s Third Corps under General A. P. Hill approached Gettysburg from the west, they were met by Union cavalry under the leadership of General John Buford. Dismounted and formed up south to north across the Chambersburg Pike, Buford’s men held off Confederate infantry until relieved by the arrival of the Union First Corps. As he deployed his men, the First Corps’ commander, General John F. Reynolds of Lancaster, was struck by a bullet and killed.

If you visit the Gettysburg battlefield, you can find the General John C. Robinson monument at the site of his division’s first-day position along Doubleday Avenue at Robinson Avenue near the Eternal Light Peace Memorial. But that’s not the Robinson we went to Gettysburg to see.

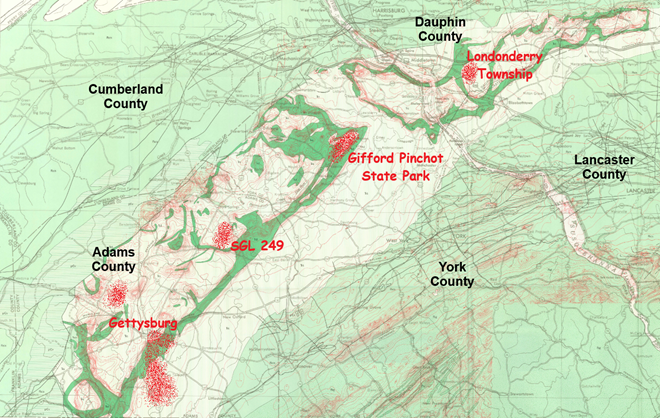

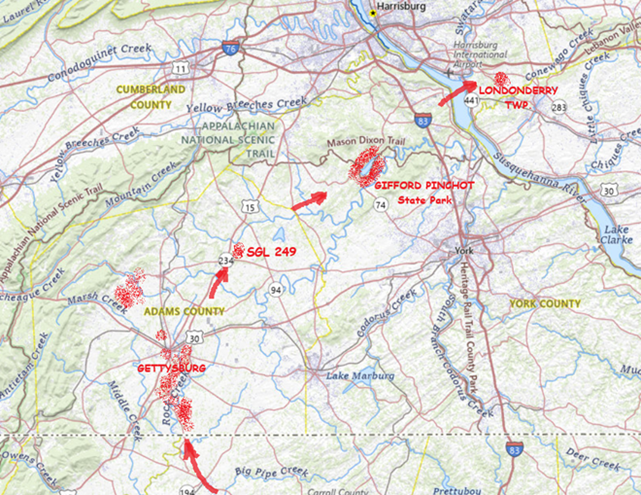

Following up on our sight and mostly sound experiences with some Robinson’s Cicadas, an annual species of singing insect we found thriving at Gifford Pinchot State Park in York County, Pennsylvania, during late July, we spent some time searching out other locations where this native invader from the southern United States could be occurring in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

During mid-August, we stumbled upon a population of Robinson’s Cicadas east of the Susquehanna in the Conewago Creek (east) watershed in Londonderry Township, Dauphin County, and made some sound recordings.

After pondering this latest discovery, we decided to investigate places with habitat characteristics similar to those at both the new Londonderry Township and the earlier Gifford Pinchot State Park locations—successional growth with extensive stands of Eastern Red Cedar on the Piedmont’s Triassic Gettysburg Formation “redbeds”. We headed south towards known populations of Robinson’s Cicadas in Virginia and Maryland to look for suitable sites within Pennsylvania that might bridge the range gap.

Our search was a rapid success. On State Game Lands 249 in the Conewago Creek (west) watershed in Adams County, we found Robinson’s Cicadas to be widespread.

Following our hunch that these lower Susquehanna Robinson’s Cicadas extended their range north through the cedar thickets of the Gettysburg Basin as opposed to hopping the Appalachians from a population reported to inhabit southwest Pennsylvania, we made our way to the battlefield and surrounding lands. We found Robinson’s Cicadas to be quite common and widespread in these areas, even occurring in the town of Gettysburg itself.