It looks like the worst of the cold may be behind us. With temperatures trending upwards during the coming days and weeks, some species of wildlife will soon find their search for food made a whole lot easier.

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

It looks like the worst of the cold may be behind us. With temperatures trending upwards during the coming days and weeks, some species of wildlife will soon find their search for food made a whole lot easier.

With another round of single-digit and possibly sub-zero temperatures on the way, birds and other wildlife are taking advantage of a break in the extreme conditions to re-energize. During the past day, these species were among those attracted to the food and cover provided by the habitat plantings in the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters garden…

For overwintering birds and other animals, finding enough food is especially difficult when there’s snow on the ground. And nighttime temperatures in the single digits make critical the need to replenish energy during the daylight hours. Earlier this afternoon, we found these American Robins seizing the berry-like cones from ornamental junipers in a grocery store parking lot. It was an urgent effort in their struggle for survival.

County conservation district offices will soon be taking orders for their spring tree sales. Be sure to load up on plenty of the species that offer food, cover, and nesting sites for birds and other wildlife. These sales are an economical way of adding dense-growing clusters or temperature-moderating groves of evergreens to your landscape. Plus, selecting four or five shrubs for every tree you plant can help establish a shelter-providing understory or hedgerow on your refuge. Nearly all of the varieties included in these sales produce some form of wildlife food, whether it be seeds, nuts, cones, berries, or nectar. Many are host plants for butterflies too. Acquiring plants from your county conservation district is a great opportunity to reduce the amount of ground you’re mowing and thus exposing to runoff and erosion as well!

Here are a few more late-season migrants you might currently see passing through the lower Susquehanna valley. Where adequate food and cover are available, some may remain into part or all of the winter…

Having experienced our first frost throughout much of the lower Susquehanna valley last night, we can look forward to seeing some changes in animal behavior and distribution in the days and weeks to come. Here are a few examples…

Currently in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, you can find these five species of herbaceous plants in full bloom. As they grow, they and others like them help to purify waters within their respective ecosystems by taking up nutrients—namely, the nitrogen and phosphorus that can lead to detrimental algal blooms and eutrophication in ponds, lakes, streams, and rivers.

Let us travel through time for just a little while to recall those sunny, late-spring days down on the farm—back when the rural landscape was a quiet, semi-secluded realm with little in the way of traffic, housing projects, or industrialized agriculture. Those among us who grew up on one of these family homesteads, or had friends who did, remember the joy of exploring the meadows, thickets, soggy springs, and woodlots they protected.

For many of us, farmland was the first place we encountered and began to understand wildlife. Vast acreage provided an abundance of space to explore. And the discovery of each new creature provided an exciting experience.

Today, high-intensity agriculture, relentless mowing, urban sprawl, and the increasing costs and demand for land have all conspired to seriously deplete habitat quality and quantity for many of the species we used to see on the local farm. Unfortunately for them, farm wildlife has largely been the victim of modern economics.

For old time’s sake, we recently passed a nostalgic afternoon at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area examining what maintenance of traditional farm habitat has done and can do for breeding birds. Join us for a quick tour to remember how it used to be at the farm next door…

We’ve seen worse, but this winter has been particularly tough for birds and mammals in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Due to the dry conditions of late summer and fall in 2024, the wild food crop of seeds, nuts, berries, and other fare has been less than average. The cold temperatures make insects hard to come by. Let’s have a look at how some of our local generalist and specialist species are faring this winter.

Wildlife certainly has a tough time making it through the winter in the lower Susquehanna valley. Establishing and/or protecting habitat that includes plenty of year-round cover and sources of food and water can really give generalist species a better chance of survival. But remember, the goal isn’t to create unnatural concentrations of wildlife, it is instead to return the landscape surrounding us into more of a natural state. That’s why we try to use native plants as much as possible. And that’s why we try to attract not only a certain bird, mammal, or other creature, but we try to promote the development of a naturally functioning ecosystem with a food web, a diversity of pollinating plants, pollinating insects, and so on. Through this experience, we stand a better chance of understanding what it takes to graduate to the bigger job at hand—protecting, enhancing, and restoring habitats needed by specialist species. These are efforts worthy of the great resources that are sometimes needed to make them a success. It takes a mindset that goes beyond a focus upon the welfare of each individual animal to instead achieve the discipline to concentrate long-term on the projects and processes necessary to promote the health of the ecosystems within which specialist species live and breed. It sounds easier than it is—the majority of us frequently become distracted.

On the wider scale, it’s of great importance to identify and protect the existing and potential future habitats necessary for the survival of specialist species. And we’re not saying that solely for their benefit. These protection measures should probably include setting aside areas on higher ground that may become the beach intertidal zone or tidal marsh when the existing ones become inundated. And it may mean finally getting out of the wetlands, floodplains, and gullies to let them be the rain-absorbing, storm-buffering, water purifiers they spent millennia becoming. And it may mean it’s time to give up on building stick structures on tinderbox lands, especially hillsides and rocky outcrops with shallow, eroding soils that dry to dust every few years. We need to think ahead and stop living for the view. If you want to enjoy the view from these places, go visit and take plenty of pictures, or a video, that’s always nice—then live somewhere else. Each of these areas includes ecosystems that meet the narrow habitat requirements of many of our specialist species, and we’re building like fools in them. Then we feign victimhood and solicit pity when the calamity strikes: fires, floods, landslides, and washouts—again and again. Wouldn’t it be a whole lot smarter to build somewhere else? It may seem like a lot to do for some specialist animals, but it’s not. Because, you see, we should and can live somewhere else—they can’t.

Our wildlife has been having a tough winter. The local species not only contend with cold and stormy weather, but they also need to find food and shelter in a landscape that we’ve rendered sterile of these essentials throughout much of the lower Susquehanna valley’s farmlands, suburbs, and cities.

Planting trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses that benefit our animals can go a long way, often turning a ho-hum parcel of property into a privately owned oasis. Providing places for wildlife to feed, rest, and raise their young can help assure the survival of many of our indigenous species. With a little dedication, you can be liberated from the chore of manicuring a lawn and instead spend your time enjoying the birds, mammals, insects, and other creatures that will visit your custom-made habitat.

Fortunately for us, our local county conservation districts are again conducting springtime tree sales offering a variety of native and beneficial cultivated plants at discount prices. Listed here are links to information on how to pre-order your plants for pickup in April. Click away to check out the species each county is offering in 2025!

Cumberland County Conservation District Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 21, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 24, 2025 or Friday, April 25, 2025

Dauphin County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Monday, March 17, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 24, 2025 or Friday, April 25, 2025

Franklin County Conservation District Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Wednesday, March 19, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 24, 2025

Lancaster County Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 7, 2025

Pickup on: Friday, April 11, 2025

Lebanon County Conservation District Tree and Plant Sale—

Orders due by: Monday, March 3, 2025

Pickup on: Friday, April 18, 2025

York County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: March 15, 2025

Pickup on: Thursday, April 10, 2025

If you live in Adams County, Pennsylvania, you may be eligible to receive free trees and shrubs for your property from the Adams County Planting Partnership (Adams County Conservation District and the Watershed Alliance of Adams County). These trees are provided by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Keystone 10-Million Trees Partnership which aims to close a seven-year project in 2025 by realizing the goal of planting 10 million trees to protect streams by stabilizing soils, taking up nutrients, reducing stormwater runoff, and providing shade. If you own property located outside of Adams County, but still within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed (which includes all of the Susquehanna, Juniata, and Potomac River drainages), you still may have an opportunity to get involved. Contact your local county conservation district office or watershed organization for information.

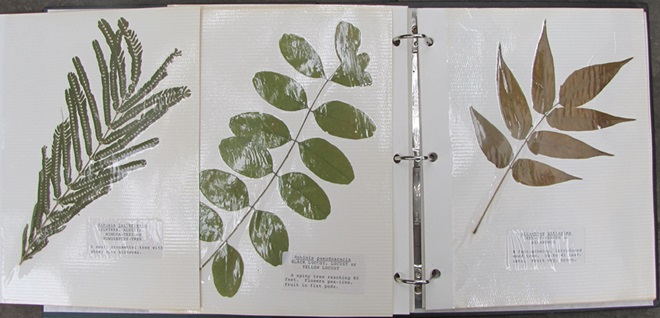

We hope you’re already shopping. Need help making your selections? Click on the “Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines” tab at the top of this page to check out Uncle Tyler Dyer’s leaf collection. He has most of the species labelled with their National Wetland Plant List Indicator Rating. You can consult these ratings to help find species suited to the soil moisture on your planting site(s). For example: if your site has sloped upland ground and/or the soils sometimes dry out in summer, select plants with a rating such as UPL or FACU. If your planting in soils that remain moist or wet, select plants with the OBL or FACW rating. Plants rated FAC are generally adaptable and can usually go either way, but may not thrive or survive under stressful conditions in extremely wet or dry soils.

NATIONAL WETLAND PLANT LIST INDICATOR RATING DEFINITIONS

Using these ratings, you might choose to plant Pin Oaks (FACW) and Swamp White Oaks (FACW) in your riparian buffer along a stream; Northern Red Oaks (FACU) and White Oaks (FACU) in the lawn or along the street, driveway, or parking area; and Chestnut Oaks (UPL) on your really dry hillside with shallow soil. Give it a try.

Each spring and fall, Purple Finches are regular migrants through the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Northbound movements usually peak in April and early May. During the summer, these birds nest primarily in cool coniferous forests to our north. Then, in October and November each year, they make another local appearance on their way to wintering grounds in the southeastern United States. A significant population of Purple Finches remains to our north through the colder months, inhabiting spruce-pine and mixed forests from the Great Lakes east through New England and southeastern Canada. This population can be irruptive, moving south in conspicuous numbers to escape inclement weather, food shortages, and other environmental conditions. Every few years, these irruptive birds can be found visiting suburbs, parks, and feeding stations—sometimes lingering in areas not often visited by Purple Finches. Right now, Purple Finches in flocks larger than those that moved through earlier in the fall are being seen throughout the lower Susquehanna valley. Snow and blustery weather to our north may be prompting these birds to shift south for a visit. Here are some looks at members of a gathering of more than four dozen Purple Finches we’ve been watching in Lebanon County this month…

As the autumn bird migration draws to a close for 2024, we’re delighted to be finding five of our favorite visitors from the coniferous and mixed forests of Canada and the northernmost continental United States.

While right now is the best time to get out and look for these species from the northern forests, any or all of them could linger into the winter months, particularly where the food supply is sufficient and conifers and other evergreens provide cover from the blustery weather.

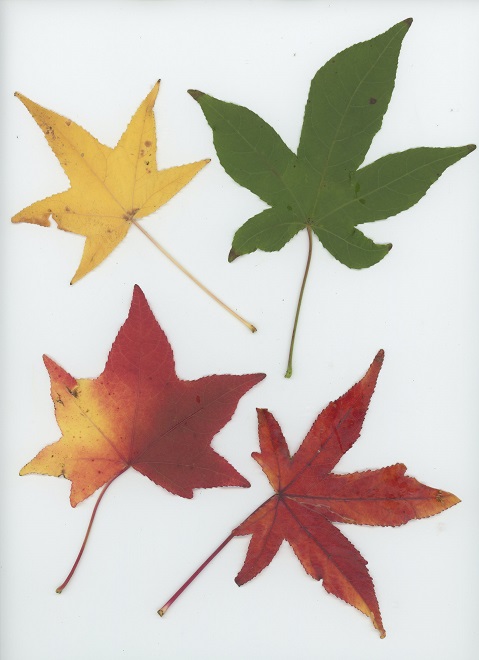

During the past week, Uncle Tyler Dyer has been out searching for autumn leaves to add to his collection. One of the species he had not encountered in previous outings was the American Elm (Ulmus americana), so he made a special trip to see a rare mammoth specimen in a small neighborhood park (Park Place) along Chestnut Street between 5th and Quince Streets in Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

There’s still time to get out and see autumn foliage. With warmer weather upon us—at least temporarily—it’s a good time to go for a stroll. Who knows, you might find some spectacular leaves like these collected by Uncle Ty earlier this week. All were found adorning native plants!

The deluge of rain that soaked the lower Susquehanna watershed during last week is now just a memory. Streams to the west of the river, where the flooding courtesy of the remnants of Hurricane Debby was most severe, have reached their crest and receded. Sliding away toward the Chesapeake and Atlantic is all that runoff, laden with a brew of pollutants including but not limited to: agricultural nutrients, sediment, petroleum products, sewage, lawn chemicals, tires, dog poop, and all that litter—paper, plastics, glass, Styrofoam, and more. For aquatic organisms including our freshwater fish, these floods, particularly when they occur in summer, can compound the effects of the numerous stressors that already limit their ability to live, thrive, and reproduce.

One of those preexisting stressors, high water temperature, can be either intensified or relieved by summertime precipitation. Runoff from forested or other densely vegetated ground normally has little impact on stream temperature. But segments of waterways receiving significant volumes of runoff from areas of sun-exposed impervious ground will usually see increases during at least the early stages of a rain event. Fortunately, projects implemented to address the negative impacts of stormwater flow and stream impairment can often have the additional benefit of helping to attenuate sudden rises in stream temperature.

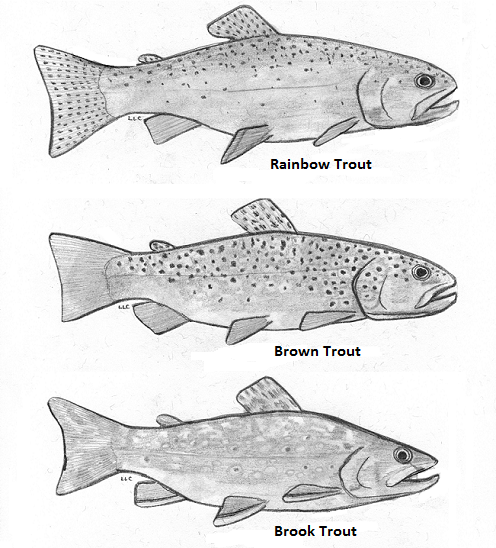

Of the fishes inhabiting the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s temperate streams, the least tolerant of summer warming are the trouts and sculpins—species often described as “coldwater fishes”. Coldwater fishes require water temperatures below 70° Fahrenheit to thrive and reproduce. The optimal temperature range is 50° to 65° F. In the lower Susquehanna valley, few streams are able to sustain trouts and sculpins through the summer months—largely due to the effects of warm stormwater runoff and other forms of impairment.

Coldwater fishes are generally found in small spring-fed creeks and headwaters runs. Where stream gradient, substrate, dissolved oxygen, and other parameters are favorable, some species may be tolerant of water warmer than the optimal values. In other words, these temperature classifications are not set in stone and nobody ever explained ichthyology to a fish, so there are exceptions. The Brown Trout for example is sometimes listed as a “coldwater transition fish”, able to survive and reproduce in waters where stream quality is exceptionally good but the temperature may periodically reach the mid-seventies.

More tolerant of summer heat than the trouts, sculpins, and daces are the “coolwater fishes”—species able to feed, grow, and reproduce in streams with a temperature of less than 80° F, but higher than 60° F. Coolwater fishes thrive in creeks and rivers that hover in the 65° to 70° F range during summer.

What are the causes of modern-day reductions in coldwater and coolwater fish habitats in the lower Susquehanna River and its hundreds of miles of tributaries? To answer that, let’s take a look at the atmospheric, cosmic, and hydrologic processes that impact water temperature. Technically, these processes could be measured as heat flux—the rate of heat energy transfer per unit area per unit time, frequently expressed as watts per meter squared (W/m²). Without getting too technical, we’ll just take a look at the practical impact these processes have on stream temperatures.

HEAT FLUX PROCESSES IN A SEGMENT OF STREAM

Now that we have a basic understanding of the heat flux processes responsible for determining the water temperatures of our creeks and rivers, let’s venture a look at a few graphics from gauge stations on some of the lower Susquehanna’s tributaries equipped with appropriate United States Geological Survey monitoring devices. While the data from each of these stations is clearly noted to be provisional, it can still be used to generate comparative graphics showing basic trends in easy-to-monitor parameters like temperature and stream flow.

Each image is self-labeled and plots stream temperature in degrees Fahrenheit (bold blue) and stream discharge in cubic feet per second (thin blue).

The daily oscillations in temperature reflect the influence of several heat flux processes. During the day, solar (shortwave) radiation and convection from summer air, especially those hot south winds, are largely responsible for the daily rises of about 5° F. Longwave radiation has a round-the-clock influence—adding heat to the stream during the day and mostly shedding it at night. Atmospheric exchange including evaporative cooling may help moderate the rise in stream temperatures during the day, and certainly plays a role in bringing them back down after sunset. Along its course this summer, the West Conewago Creek absorbed enough heat to render it a warmwater fishery in the area of the gauging station. The West Conewago is a shallow, low gradient stream over almost its entire course. Its waters move very slowly, thus extending their exposure time to radiated heat flux and reducing the benefit of cooling by atmospheric exchange. Fortunately for bass, catfish, and sunfish, these temperatures are in the ideal range for warmwater fishes to feed, grow, and reproduce—generally over 80° F, and ideally in the 70° to 85° F range. Coolwater fishes though, would not find this stream segment favorable. It was consistently above the 80° F maximum and the 60° to 70° F range preferred by these species. And coldwater fishes, well, they wouldn’t be caught dead in this stream segment. Wait, scratch that—the only way they would be caught in this segment is dead. No trouts or sculpins here.

Look closely and you’ll notice that although the temperature pattern on this chart closely resembles that of the West Conewago’s, the readings average about 5 degrees cooler. This may seem surprising when one realizes that the Codorus follows a channelized path through the heart of York City and its urbanized suburbs—a heat island of significance to a stream this size. Before that it passes through numerous impoundments where its waters are exposed to the full energy of the sun. The tempering factor for the Codorus is its baseflow. Despite draining a smaller watershed than its neighbor to the north, the Codorus’s baseflow (low flow between periods of rain) was 96 cubic feet per second on August 5th, nearly twice that of the West Conewago (51.1 cubic feet per second on August 5th). Thus, the incoming heat energy was distributed over a greater mass in the Codorus and had a reduced impact on its temperature. Though the Codorus is certainly a warmwater fishery in its lower reaches, coolwater and transitional fishes could probably inhabit its tributaries in segments located closer to groundwater sources without stress. Several streams in its upper reaches are in fact classified as trout-stocked fisheries.

The Kreutz Creek gauge shows temperature patterns similar to those in the West Conewago and Codorus data sets, but notice the lower overall temperature trend and the flow. Kreutz Creek is a much smaller stream than the other two, with a flow averaging less than one tenth that of the West Conewago and about one twentieth of that in the Codorus. And most of the watershed is cropland or urban/suburban space. Yet, the stream remains below 80° F through most of the summer. The saving graces in Kreutz Creek are reduced exposure time and gradient. The waters of Kreutz Creek tumble their way through a small watershed to enter the Susquehanna within twenty-four hours, barely time to go through a single daily heating and cooling cycle. As a result, their is no chance for water to accumulate radiant and convective heat over multiple summer days. The daily oscillations in temperature are less amplified than we find in the previous streams—a swing of about three degrees compared to five. This indicates a better balance between heat flux processes that raise temperature and those that reduce it. Atmospheric exchange in the stream’s riffles, forest cover, and good hyporheic exchange along its course could all be tempering factors in Kreutz Creek. From a temperature perspective, Kreutz Creek provides suitable waters for coolwater fishes.

Muddy Creek is a trout-stocked fishery, but it cannot sustain coldwater species through the summer heat. Though temperatures in Muddy Creek may be suitable for coolwater fishes, silt, nutrients, low dissolved oxygen, and other factors could easily render it strictly a warmwater fishery, inhabited by species tolerant of significant stream impairment.

A significant number of stream segments in the Chiques watershed have been rehabilitated to eliminate intrusion by grazing livestock, cropland runoff, and other sources of impairment. Through partnerships between a local group of watershed volunteers and landowners, one tributary, Donegal Creek, has seen riparian buffers, exclusion fencing, and other water quality and habitat improvements installed along nearly ever inch of its run from Donegal Springs through high-intensity farmland to its mouth on the main stem of the Chiques just above its confluence with the Susquehanna. The improved water quality parameters in the Donegal support native coldwater sculpins and an introduced population of reproducing Brown Trout. While coldwater habitat is limited to the Donegal, the main stem of the Chiques and its largest tributary, the Little Chiques Creek, both provide suitable temperatures for coolwater fishes.

Despite its meander through and receipt of water from high-intensity farmland, the temperature of the lower Conewago (East) maxes out at about 85° F, making it ideal for warmwater fishes and even those species that are often considered coolwater transition fishes like introduced Smallmouth Bass, Rock Bass, Walleye, and native Margined Madtom. This survivable temperature is a testament to the naturally occurring and planted forest buffers along much of the stream’s course, particularly on its main stem. But the Conewago suffers serious baseflow problems compared to other streams we’ve looked at so far. Just prior to the early August storms, flow was well below 10 cubic feet per second for a drainage area of more than fifty square miles. While some of this reduced flow is the result of evaporation, much of it is anthropogenic in origin as the rate of groundwater removal continues to increase and a recent surge in stream withdraws for irrigation reaches its peak during the hottest days of summer.

A little side note—the flow rate on the Conewago at the Falmouth gauge climbed to about 160 cubic feet per second as a result of the remnants of Hurricane Debby while the gauge on the West Conewago at Manchester skyrocketed to about 20,000 cubic feet per second. Although the West Conewago’s watershed (drainage area) is larger than that of the Conewago on the east shore, it’s larger only by a multiple of two or three, not 125. That’s a dramatic difference in rainfall!

The temperatures at the Bellaire monitoring station, which is located upstream of the Conewago’s halfway point between its headwaters in Mount Gretna and its mouth, are quite comparable to those at the Falmouth gauge. Although a comparison between these two sets of data indicate a low net increase in heat absorption along the stream’s course between the two points, it also suggests sources of significant warming upstream in the areas between the Bellaire gauge and the headwaters.

The waters of the Little Conewago are protected within planted riparian buffers and mature woodland along much of their course to the confluence with the Conewago’s main stem just upstream of Bellaire. This tributary certainly isn’t responsible for raising the temperature of the creek, but is instead probably helping to cool it with what little flow it has.

Though mostly passing through natural and planted forest buffers above its confluence with the Little Conewago, the main stem’s critically low baseflow makes it particularly susceptible to heat flux processes that raise stream temperatures in segments within the two or three large agricultural properties where owners have opted not to participate in partnerships to rehabilitate the waterway. The headwaters area, while largely within Pennsylvania State Game Lands, is interspersed with growing residential communities where potable water is sourced from hundreds of private and community wells—every one of them removing groundwater and contributing to the diminishing baseflow of the creek. Some of that water is discharged into the stream after treatment at the two municipal sewer plants in the upper Conewago. This effluent can become quite warm during processing and may have significant thermal impact when the stream is at a reduced rate of flow. A sizeable headwaters lake is seasonally flooded for recreation in Mount Gretna. Such lakes can function as effective mid-day collectors of solar (shortwave) radiation that both warms the water and expedites atmospheric exchange.

Though Conewago Creek (East) is classified as a trout-stocked fishery in its upper reaches in Lebanon County, its low baseflow and susceptibility to warming render it inhospitable to these coldwater fishes by late-spring/early summer.

The removal of two water supply dams on the headwaters of Hammer Creek at Rexmont eliminated a large source of temperature fluctuation on the waterway, but did little to address the stream’s exposure to radiant and convective heat flux processes as it meanders largely unprotected out of the forest cover of Pennsylvania State Game Lands and through high-intensity farmlands in the Lebanon Valley. Moderating the temperature to a large degree is the influx of karst water from Buffalo Springs, located about two miles upstream from this gauging station, and other limestone springs that feed tributaries which enter the Hammer from the east and north. Despite the cold water, the impact of the stream’s nearly total exposure to radiative and other warming heat flux processes can readily be seen in the graphic. Though still a coldwater fishery by temperature standards, it is rather obvious that rapid heating and other forms of impairment await these waters as they continue flowing through segments with few best management practices in place for mitigating pollutants. By the time Hammer Creek passes back through the Furnace Hills and Pennsylvania State Game Lands, it is leaning toward classification as a coolwater fishery with significant accumulations of sediment and nutrients. But this creek has a lot going for it—mainly, sources of cold water. A core group of enthusiastic landowners could begin implementing the best management practices and undertaking the necessary water quality improvement projects that could turn this stream around and make it a coldwater treasure. An organized effort is currently underway to do just that. Visit Trout Unlimited’s Don Fritchey Chapter and Donegal Chapter to learn more. Better yet, join them as a volunteer or cooperating landowner!

For coldwater fishes, the thousands of years since the most recent glacial maximum have seen their range slowly contract from nearly the entirety of the once much larger Susquehanna watershed to the headwaters of only our most pristine streams. Through no fault of their own, they had the misfortune of bad timing—humans arrived and found coldwater streams and the groundwater that feeds them to their liking. Some of the later arrivals even built their houses right on top of the best-flowing springs. Today, populations of these fishes in the region we presently call the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed are seriously disconnected and the prospect for survival of these species here is not good. Stream rehabilitation, groundwater management, and better civil planning and land/water stewardship are the only way coldwater fishes, and very possibly coolwater fishes as well, will survive. For some streams like Hammer Creek, it’s not too late to make spectacular things happen. It mostly requires a cadre of citizens, local government, project specialists, and especially stakeholders to step up and be willing to remain focused upon project goals so that the many years of work required to turn a failing stream around can lead to success.

You’re probably glad this look at heat flux processes in streams has at last come to an end. That’s good, because we’ve got a lot of work to do.

Do you recall our “Photo of the Day” from seven months ago…

Well, here’s what that site looks like today…

And there are pollinating insects galore, most notably butterflies…

Why on earth would anyone waste their time, energy, and money mowing grass when they could have this? Won’t you please consider committing graminicide this fall? That’s right, kill that lawn—at least the majority of it. Then visit the Ernst Seed website, buy some “Native Northeast Wildlflower Mix” and/or other blends, and get your meadow planted in time for the 2025 growing season. Just think of all the new kinds of native plants and animals you’ll be seeing. It could change your life as well as theirs.

It’s that time of year. Your local county conservation district is taking orders for their annual tree sale and it’s a deal that can’t be beat. Order now for pickup in April.

The prices are a bargain and the selection includes the varieties you need to improve wildlife habitat and water quality on your property. For species descriptions and more details, visit each tree sale web page (click the sale name highlighted in blue). And don’t forget to order packs of evergreens for planting in mixed clumps and groves to provide winter shelter and summertime nesting sites for our local native birds. They’re only $12.00 for a bundle of 10.

Cumberland County Conservation District Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 22, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 18, 2024 or Friday, April 19, 2024

Dauphin County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Monday, March 18, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 18, 2024 or Friday, April 19, 2024

Lancaster County Annual Tree Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 8, 2024

Pickup on: Friday, April 12, 2024

Lebanon County Conservation District Tree and Plant Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 8, 2024

Pickup on: Friday, April 19, 2024

Perry County Conservation District Tree Sale—

Orders due by: Sunday, March 24, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 11, 2024

Again this year, Perry County is offering bluebird nest boxes for sale. The price?—just $12.00.

York County Conservation District Seedling Sale—

Orders due by: Friday, March 15, 2024

Pickup on: Thursday, April 11, 2024

To get your deciduous trees like gums, maples, oaks, birches, and poplars off to a safe start, conservation district tree sales in Cumberland, Dauphin, Lancaster, and Perry Counties are offering protective tree shelters. Consider purchasing these plastic tubes and supporting stakes for each of your hardwoods, especially if you have hungry deer in your neighborhood.

There you have it. Be sure to check out each tree sale’s web page to find the selections you like, then get your order placed. The deadlines will be here before you know it and you wouldn’t want to miss values like these!

Since Tuesday’s snow storm, the susquehannawiildlife.net headquarters garden continues to bustle with bird activity.

Today, there arrived three species of birds we haven’t seen here since autumn. These birds are, at the very least, beginning to wander in search of food. Then too, these may be individuals creeping slowly north to secure an advantage over later migrants by being the first to establish territories on the most favorable nesting grounds.

They say the early bird gets the worm. More importantly, it gets the most favorable nesting spot. What does the early birder get? He or she gets out of the house and enjoys the action as winter dissolves into the miracle of spring. Do make time to go afield and marvel a bit, won’t you? See you there!

In mid-February each year, large numbers of American Robins descend upon the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters garden to feast on the ripe fruits that adorn several species of our native shrubs and trees. This morning’s wet snowfall provided the needed motivation for these birds and others to make today the big day for the annual feeding frenzy.

With the earth at perihelion (its closest approach to the sun) and with our home star just 27 degrees above the horizon at midday, bright low-angle light offered the perfect opportunity for doing some wildlife photography today. We visited a couple of grasslands managed by the Pennsylvania Game Commission to see what we could find…

A glimpse of the rowdy guests crowding the Thanksgiving Day dinner table at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters…

As the annual autumn songbird migration begins to reach its end, native sparrows can be found concentrating in fallow fields, early successional thickets, and brushy margins along forest edges throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

Visit native sparrow habitat during mid-to-late November and you have a good chance of seeing these species and more…

If you’re lucky enough to live where non-native House Sparrows won’t overrun your bird feeders, you can offer white millet as a supplement to the wild foods these beautiful sparrows might find in your garden sanctuary. Give it a try!

Have you noticed? Foliage throughout the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed has been painted with the brilliant colors of autumn, so now is the time to get out there and have a look. Why not make a collection? You can pick up an inexpensive scrap book or photo album at the craft store to press and label the varieties you find. Uncle Tyler Dyer is already busy adding to the project he assembled last year. You can use his exhibit as a reference for identifying and learning a little bit more about the leaves you find.