You may find this hard to believe, but during the colder months in the lower Susquehanna valley, gulls aren’t as numerous as they used to be. In the years since their heyday in the late twentieth century, many of these birds have chosen to congregate in other areas of the Mid-Atlantic region where the foods they crave are more readily available.

As you may have guessed, the population boom of the 1980s and 1990s was largely predicated on human activities. These four factors were particularly beneficial for wintering gulls…

-

-

- Disposal of food-bearing waste in open landfills

- High-intensity agriculture with disc plowing

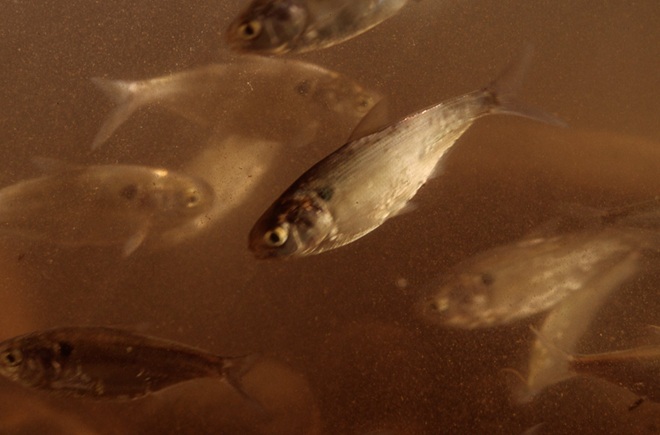

- Gizzard Shad population boom in nutrient-impaired river/Hydroelectric power generation

- Fumbled Fast Food

-

So what happened? Why are wintering gulls going elsewhere and no longer concentrating on the Susquehanna? Well, let’s look at what has changed with our four man-made factors…

-

-

- A larger percentage of the lower Susquehanna basin’s household and food industry waste is now incinerated/Landfills practice “cover as you go” waste burial.

- Implementation of “no-till” farming has practically eliminated availability of earthworms and other sub-surface foods for gulls.

- The population explosion of invasive Asiatic Clams has reduced the Gizzard Shad’s relative abundance and biomass among filter feeders.

- Hold on tight! Fast food has become too expensive to waste.

-

GULLS THIS WINTER

Despite larid abundance on the lower Susquehanna not being the spectacle it was during the man-made boom days, an observer can still find a variety of medium and large-sized gulls wintering in the region. We ventured out to catch a glimpse of some of the species being seen both within the watershed and very nearby.

For us, seeing a Glaucous Gull brought back memories of the last time we saw the species. It was forty-five years ago on New Year’s Day 1981 that we discovered two first-winter birds feeding on Gizzard Shad in open water on an otherwise ice-choked Susquehanna below the York Haven Dam powerhouse at Conewago Falls. Hey Doc Robert, do you remember that day?