Photo of the Day

LIFE IN THE LOWER SUSQUEHANNA RIVER WATERSHED

A Natural History of Conewago Falls—The Waters of Three Mile Island

As we begin the second half of October, frosty nights have put an end to choruses of annual cicadas in the lower Susquehanna valley. Though they are gone for yet another year, they are not forgotten. Here’s an update on one of our special finds in 2025.

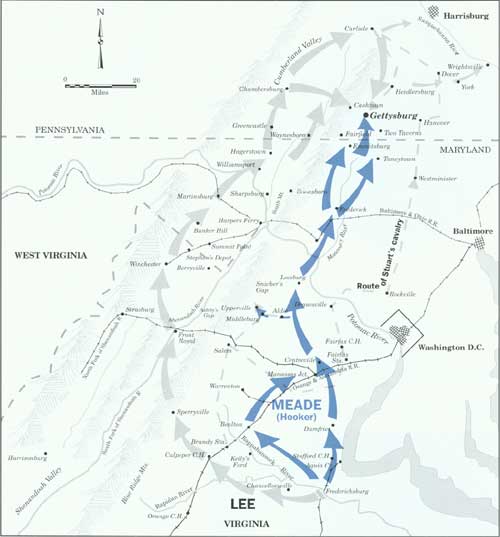

During late June of 1863, the beginning of the third summer of the American Civil War, there was great consternation among the populous of the lower Susquehanna region. Hoping to bring about Union capitulation and an end to the conflict, General Robert E. Lee and his 70,000-man Army of Northern Virginia were marching north into the passes and valleys on the west side of the river. The uncontested Confederate advances posed an immediate threat to Pennsylvania’s capital in Harrisburg and cities to the east. Marching north in pursuit of Lee was the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac, the lead element of the 100,000-man Union force under the direction of newly appointed commander General George G. Meade.

Upon belatedly learning of Meade’s pursuit, Lee hastily ordered the widely separated corps of his army to concentrate on the crossroads town of Gettysburg. As the southern army’s Third Corps under General A. P. Hill approached Gettysburg from the west, they were met by Union cavalry under the leadership of General John Buford. Dismounted and formed up south to north across the Chambersburg Pike, Buford’s men held off Confederate infantry until relieved by the arrival of the Union First Corps. As he deployed his men, the First Corps’ commander, General John F. Reynolds of Lancaster, was struck by a bullet and killed.

If you visit the Gettysburg battlefield, you can find the General John C. Robinson monument at the site of his division’s first-day position along Doubleday Avenue at Robinson Avenue near the Eternal Light Peace Memorial. But that’s not the Robinson we went to Gettysburg to see.

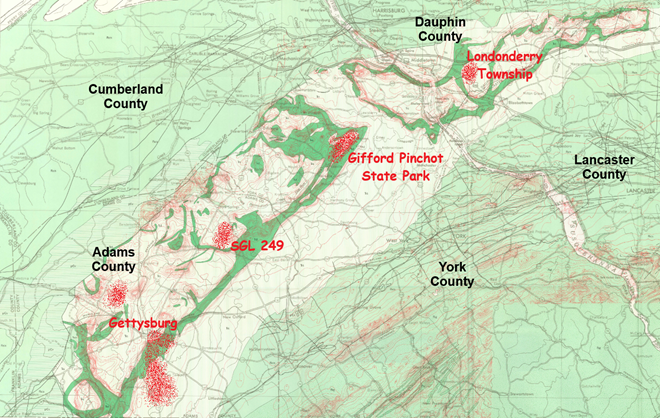

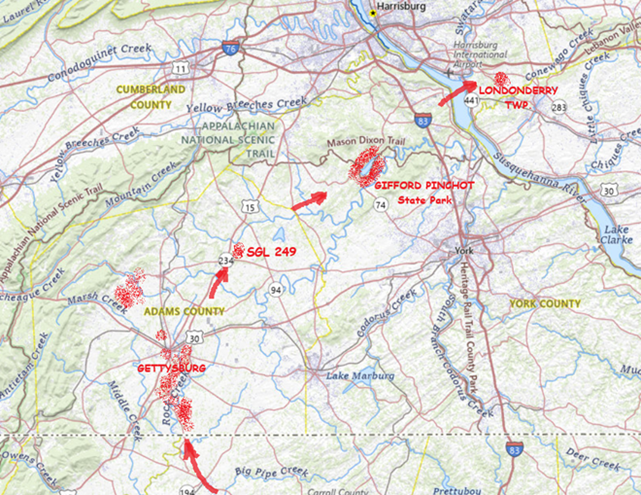

Following up on our sight and mostly sound experiences with some Robinson’s Cicadas, an annual species of singing insect we found thriving at Gifford Pinchot State Park in York County, Pennsylvania, during late July, we spent some time searching out other locations where this native invader from the southern United States could be occurring in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

During mid-August, we stumbled upon a population of Robinson’s Cicadas east of the Susquehanna in the Conewago Creek (east) watershed in Londonderry Township, Dauphin County, and made some sound recordings.

After pondering this latest discovery, we decided to investigate places with habitat characteristics similar to those at both the new Londonderry Township and the earlier Gifford Pinchot State Park locations—successional growth with extensive stands of Eastern Red Cedar on the Piedmont’s Triassic Gettysburg Formation “redbeds”. We headed south towards known populations of Robinson’s Cicadas in Virginia and Maryland to look for suitable sites within Pennsylvania that might bridge the range gap.

Our search was a rapid success. On State Game Lands 249 in the Conewago Creek (west) watershed in Adams County, we found Robinson’s Cicadas to be widespread.

Following our hunch that these lower Susquehanna Robinson’s Cicadas extended their range north through the cedar thickets of the Gettysburg Basin as opposed to hopping the Appalachians from a population reported to inhabit southwest Pennsylvania, we made our way to the battlefield and surrounding lands. We found Robinson’s Cicadas to be quite common and widespread in these areas, even occurring in the town of Gettysburg itself.

Just as we were very pleased last month to have the opportunity to hear the sounds of the rarest of the Periodical Cicadas—the Little Seventeen-year Cicada—in the Conewago Hills of York County to thus provide our only record of the species during the Brood XIV emergence in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, we were this week delighted to find and record a population of what may be the valley’s rarest cicada experiencing annual flights—the Robinson’s Cicada—just a few miles away at Gifford Pinchot State Park.

Like the Little Seventeen-year Cicada, Robinson’s Cicada (Neotibicen robinsonianus) is a species found more commonly in the southern United States, occurring with scattered distribution in a range that extends west into Missouri, Kansas, and Texas. They are of rare occurrence in the lands of the Chesapeake drainage basin in Virginia and Maryland.

The Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, and Gifford Pinchot State Park in particular, may currently represent the northern limit of the geographic range of the Robinson’s Cicada. If you’re in the area during the coming weeks, drop by the park and have a listen. And don’t forget to check out our “Cicadas” page for sound clips of all the species found in our area.

It begins on a sunny morning in spring each year, just as the ground temperature reaches sixty degrees or more…

Of course, termites aren’t the only groups of insects to swarm. As heated runoff from slow-moving thundershowers has increased stream temperatures during the past couple of weeks, there have occurred a number of seasonal mayfly “hatches” on the Susquehanna and its tributaries. These “hatches” are actually the nuptial flights of newly emerged imago and adult mayflies. The most conspicuous of these is the Great Brown Drake.

Swarms of another storm-related visitor are being seen throughout the lower Susquehanna valley right now. Have you noticed the Wandering Gliders?

While the heat and humidity of early summer blankets the region, Brood XIV Periodical Cicadas are wrapping up their courtship and breeding cycle for 2025. We’ve spent the past week visiting additional sites in and near the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where their emergence is evident.

We begin in York County just to the west of the river and Conewago Falls in mostly forested terrain located just southeast of Gifford Pinchot State Park. Within this area, often called the Conewago Hills, a very localized population of cicadas could be heard in the woodlands surrounding the scattered homes along Bull Road. Despite the dominant drone of an abundance of singing Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas, we were able to hear and record the courtship song of a small number of the rare Little Seventeen-year Cicadas. Their lawn sprinkler-like pulsating songs help mate-seeking males penetrate the otherwise overwhelming chorus of the Pharaoh cicadas in the area.

From the Conewago Hills we moved northwest into the section of southern Cumberland County known as South Mountain. Here, Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas were widespread in ridgetop forests along the Appalachian Trail, particularly in the area extending from Long Mountain in the east through Mount Holly to forests south of King’s Gap Environmental Education Center in the west.

While on South Mountain, we opted for a side trip into the neighboring Potomac watershed of Frederick County, Maryland, where these hills ascend to greater altitude and are known as the Blue Ridge Mountains, a name that sticks with them all the way through Shenandoah National Park, the Great Smoky Mountains, and to their southern terminus in northwestern Georgia. We found a fragmented emergence of Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas atop the Catoctin Mountain section of the Blue Ridge just above the remains of Catoctin Furnace, again on lands that had been timbered to make charcoal to fuel iron production prior to their protection as vast expanses of forest.

Back in Pennsylvania, we’re on our way to the watersheds of the northernmost tributaries of the lower Susquehanna’s largest tributary, the Juniata River. There, we found Brood XIV cicadas more widespread and in larger numbers than occurred at previous sites. Both Pharaoh and Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas were seen and heard along Jack’s Mountain and the Kishacoquillas Creek north of Lewistown/Burnham in Mifflin County. To the north of the Kishacoquillas Valley and Stone Mountain in northernmost Huntingdon County, the choruses of the two species were again widespread, particularly along the forest edges in Greenwood Furnace State Park, Rothrock State Forest, and adjacent areas of the Standing Stone Creek watershed.

Within the last 48 hours, we visited one last location in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed where Brood XIV Periodical Cicadas have emerged during 2025. In the anthracite coal country of Northumberland County, a flight of Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas is nearing its end. We found them to be quite abundant in forested areas of Zerbe Run between Big and Little Mountains around Trevorton and on the wooded slopes of Mahanoy Mountain south of nearby Shamokin. Line Mountain south of Gowen City had a substantial emergence as well.

To chart our travels, we’ve put together this map plotting the occurrence of significant flights of Periodical Cicadas during the 2025 emergence. Unlike the more densely distributed Brood X cicadas of 2021, the range of Brood XIV insects is noticeably fragmented, even in areas that are forested. We found it interesting how frequently we found Brood XIV cicadas on lands used as sources of lumber to make charcoal for fueling nineteenth-century iron furnace operations.

Well, that’s a wrap. Please don’t forget to check out our new Cicadas page by clicking the “Cicadas” tab at the top of this page. Soon after the Periodical Cicadas are gone, the annual cicadas will be emerging and our page can help you identify the five species found regularly in the lower Susquehanna valley. ‘Til next time, keep buzzing!

Here are some sights and sounds from the ongoing emergence of Brood XIV Periodical Cicadas in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed.

We begin in the easternmost spur of the lower basin where a sizeable emergence of cicadas can be seen and heard in the woodlands surrounding the headwaters of the Conestoga River in Berks County north of Morgantown. This flight extends east into Chester County and the French Creek drainage of the Schuylkill River watershed on State Game Lands 43 north of Elverson and consists of Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas (Magicicada septendecim), the most common species among 17-year broods.

From Route 82 north of Elverson to the west through the forested areas along Route 10 north of Morgantown and the Pennsylvania Turnpike, we found an abundance of Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas (Magicicada cassini) calling among the Pharaohs. This mix of Pharaoh and Cassin’s Periodical Cicadas extends west along the north side of the turnpike into Lancaster County and State Game Lands 52 on Black Creek north of Churchtown.

Further west in Cornwall, Lebanon County, a Brood XIV emergence can be found on similar forested terrain: the Triassic hills of the Newark Basin—rich in iron ore and renowned for furnace operations during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas were the only species heard among this population that extends from Route 72 east through the woodlands along Route 322 into the northern edge of State Game Lands 156 in Lancaster County.

On the west side of the Susquehanna, yet another isolated population of Brood XIV Periodical Cicadas can be found in Perry County, just south of Duncannon on State Game Lands 170 on the slopes of “Cove Mountain”, the canoe-shaped convergence of the western termini of Peters and Second Mountains.

Pharaoh Periodical Cicadas dominated this Perry County chorus,…

…but we did detect at least one Cassin’s Cicada trying to find a mate.

Not to say they aren’t present, but we have yet to detect the rarest species, Magicicada septendecula, the “Little Seventeen-year Cicada”, among the various populations of Brood XIV Periodical Cicadas emerging in the lower Susquehanna valley. For the coming two weeks or so until this brood is gone for another 17 years, the search continues.

For more on both annual and periodical cicada species in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, be sure to click the “Cicadas” tab at the top of this page!

With temperatures finally climbing to seasonable levels and with stormy sun filtering through the yellow-brown smoke coming our way courtesy of wildfires in Alberta and other parts of central Canada, we ventured out to see what might be basking in our local star’s refracted rays…

Its been four years to the day since we posted our account of the big Brood X Periodical Cicada flight of 2021 in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. With the Brood XIV clan of 17-year Periodical Cicadas getting ready fill the June air with their choruses in scattered parts of Pennsylvania’s Berks, Centre, Clinton, Franklin, Huntingdon, Juniata, Lancaster, Mifflin, Perry, Schuylkill, Snyder, Union, and York Counties right now, we thought it an appropriate time to open a new “Cicada” page here on the website. Included is a list of both the annually and periodically emerging species found in the lower Susquehanna valley, as well as a copy of the article and ID photos from the 2021 occurrence of Brood X. In coming months, we’ll be adding photos and maybe some sound clips of the different annual cicadas as well, so remember to check back from time to time for more content.

In the short term, we’re going to pay a visit to the Brood XIV territory and will bring you updates as we get them. Until then, be sure to click the new “Cicadas” tab at the top of this page to brush up on your ID of the three species of 17-year Periodical Cicadas.

Here at susquehannawildlife.net headquarters, we really enjoy looking back in time at old black-and-white pictures. We even have an old black-and-white television that still operates quite well. But on a nice late-spring day, there’s no sense sitting around looking at that stuff when we could be outside tracking down some sightings of a few wonderful animals.

Here’s a short preview of some of the finds you can expect during an outing in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed’s forests this week…

Let us travel through time for just a little while to recall those sunny, late-spring days down on the farm—back when the rural landscape was a quiet, semi-secluded realm with little in the way of traffic, housing projects, or industrialized agriculture. Those among us who grew up on one of these family homesteads, or had friends who did, remember the joy of exploring the meadows, thickets, soggy springs, and woodlots they protected.

For many of us, farmland was the first place we encountered and began to understand wildlife. Vast acreage provided an abundance of space to explore. And the discovery of each new creature provided an exciting experience.

Today, high-intensity agriculture, relentless mowing, urban sprawl, and the increasing costs and demand for land have all conspired to seriously deplete habitat quality and quantity for many of the species we used to see on the local farm. Unfortunately for them, farm wildlife has largely been the victim of modern economics.

For old time’s sake, we recently passed a nostalgic afternoon at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area examining what maintenance of traditional farm habitat has done and can do for breeding birds. Join us for a quick tour to remember how it used to be at the farm next door…

Neotropical birds are fairly well acquainted with repetitive periods of thundershowers. With that in mind, we decided not to waste this stormy Tuesday by remaining indoors.

We hope you enjoyed our walk in the rain as much as we did. If you venture out on a similar excursion, please remember this. The majority of the wild animals around us have busy lives, particularly at this time of year. Most don’t take a day off just because it rains—that includes ticks.

Here’s a look at six native shrubs and trees you can find blooming along forest edges in the lower Susquehanna valley right now.

Local old timers might remember hearing folklore that equates the northward advance of the blooming of the Flowering Dogwoods with the progress of the American Shad’s spring spawning run up the river. While this is hardly a scientific proclamation, it is likely predicated on what had been some rather consistent observation prior to the construction of the lower Susquehanna’s hydroelectric dams. In fact, we’ve found it to be a useful way to remind us that it’s time for a trip to the river shoreline below Conowingo Dam to witness signs of the spring fish migration each year. We’re headed that way now and will summarize our sightings for you in days to come.

During a warm spell back in late March, adult Mason Bees began emerging from nest sites to begin mating. During recent days, we photographed the fertile females as they continued the process that will produce the next generation of these fruit-friendly pollinators.

During the past week, Uncle Tyler Dyer has been out searching for autumn leaves to add to his collection. One of the species he had not encountered in previous outings was the American Elm (Ulmus americana), so he made a special trip to see a rare mammoth specimen in a small neighborhood park (Park Place) along Chestnut Street between 5th and Quince Streets in Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

There’s still time to get out and see autumn foliage. With warmer weather upon us—at least temporarily—it’s a good time to go for a stroll. Who knows, you might find some spectacular leaves like these collected by Uncle Ty earlier this week. All were found adorning native plants!

During your foray to view the colorful foliage of the autumn landscape, a little effort will reveal much more than meets the eye of the casual observer.

You too can experience the joys of walking and chewing gum at the same time, so grab your field glasses, your camera, and your jacket, then spend lots of time outdoors this fall. You can see all of this and much more.

Don’t forget to click the “Hawkwatcher’s Helper: Identifying Bald Eagles and other Diurnal Raptors” tab at the top of this page to help you find a place to see both fall foliage and migrating birds of prey in coming weeks. And click the “Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines” tab to find a photo guide that can help you identify the autumn leaves you encounter during your outings.

For the past several weeks, we’ve given you a look at the fallout of Neotropical songbirds on mornings following significant nocturnal flights of southbound migrants. Now let’s examine the diurnal (daytime) flights that have developed in recent days over parts of the lower Susquehanna basin and adjacent regions.

For those observing diurnal migrants, particularly at raptor-counting stations, the third week of September is prime time for large flights of tropics-bound Broad-winged Hawks. Winds from easterly directions during this year’s movements kept the greatest concentrations of these birds in the Ridge and Valley Province and upper areas of the Piedmont as they transited our region along a southwesterly heading. Counts topped 1,000 birds or more on at least one day at each of these lookouts during the past seven days. Meanwhile at hawk watches along the Piedmont/Atlantic Coastal Plain border, where flights topped 10,000 or more birds on the best days last fall, observers struggled to see 100 Broad-winged Hawks in a single day.

Among the challenges counters faced while enumerating migratory Broad-winged Hawks this week was the often clear blue skies, a glaring sun, and the high altitude at which these raptors fly during the mid-day hours.

Another factor complicating the hawk counters’ tasks this week, particularly west of the Susquehanna River, was the widespread presence of another group of diurnal fliers.

As the Broad-winged Hawk migration draws to a close during the coming ten days, the occurrence of the one dozen other migratory diurnal raptors will be on the upswing. They generally fly at lower altitudes, often relying upon wind updrafts on the ridges for lift instead of high-rising thermal updrafts. They therefore present better observation opportunities for visitors at hawk watch lookouts and are less frequently confused with high-flying Spotted Lanternflies.

Back on March 24th, we took a detailed look at the process involved in administering prescribed fire as a tool for managing grassland and early successional habitat. Today we’re going turn back the hands of time to give you a glimpse of how the treated site fared during the five months since the controlled burn. Let’s go back to Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area for a photo tour to see how things have come along…

Elsewhere around the refuge at Middle Creek, prescribed fire and other management techniques are providing high-quality grassland habitat for numerous species of nesting birds…

We hope you enjoyed this short photo tour of grassland management practices. Now, we’d like to leave you with one last set of pictures—a set you may find as interesting as we found them. Each is of a different Eastern Cottontail, a species we found to be particularly common on prescribed fire sites when we took these images in late May. The first two are of the individuals we happened to be able to photograph in areas subjected to fire two months earlier in March. The latter two are of cottontails we happened to photograph elsewhere on the refuge in areas not in proximity to ground treated with a prescribed burn or exposed to accidental fire in recent years.

These first two rabbits are living the good life in a warm-season grass wonderland.

Oh Deer! Oh Deer! These last two rabbits have no clock to track the time; they have only ticks. Better not go for a stroll with them Alice—that’s no wonderland! I know, I know, it’s time to go. See ya later.

The Aphrodite Fritillary (Speyeria aphrodite), also known simply as the Aphrodite, is a brush-footed butterfly of deciduous, coniferous, and mixed forests. We found this female in a grassland margin between woodlots where prescribed fire was administered during the autumn of 2022 to reduce accumulations of natural fuels and an overabundance of invasive vegetation. A goal of the burn was to promote the growth of native species including the violets (Viola species) favored as larval host plants by this and other fritillaries.

By the time these adult butterflies make their reproductive flights in late summer, the violets that serve as larval host plants have gone dormant. To find patches of ground where the violets will come to life in spring, the female Aphrodite Fritillary has an ability to sense the presence of dormant roots, probably by smell. Upon finding an area where suitable violets will begin greening up next year, she’ll deposit her eggs. The eggs overwinter, then hatch to feed on the tender new violet leaves of spring.

Do you recall our “Photo of the Day” from seven months ago…

Well, here’s what that site looks like today…

And there are pollinating insects galore, most notably butterflies…

Why on earth would anyone waste their time, energy, and money mowing grass when they could have this? Won’t you please consider committing graminicide this fall? That’s right, kill that lawn—at least the majority of it. Then visit the Ernst Seed website, buy some “Native Northeast Wildlflower Mix” and/or other blends, and get your meadow planted in time for the 2025 growing season. Just think of all the new kinds of native plants and animals you’ll be seeing. It could change your life as well as theirs.

Where does all the time go? Already in 2024, half the calendar is in the trash and the gasoline and gunpowder gang’s biggest holiday of the year is upon us. Instead of bringing you the memory-making odors of quick-burning sulfur or the noise and multi-faceted irritations that revved-up combustion engines bring, we thought it best to provide our readers with a taste of history for this Fourth of July. Join us, won’t you, for a look back at one of the many events that shaped the landscape of our present-day world.

The early morning’s sun had just begun bathing the verdant gardens of the olde towne centre with a warm glowing light. Birds were singing and the local folk were beginning to stir in preparation for their day’s chores. Then, suddenly, something was stirring afoot.

The great battle had commenced. Within minutes, thousands of colonists spilled onto the pavement to join the melee and defend their homes.

The fighting was at close quarters—face to face with dominant soldiers sparing no effort to prevail in the struggle.

After about an hour had passed, the tide had turned and the fighting mass drifted to the south of the battle’s starting point. The aggressors had been repelled. The dispute was resolved—at least for a little while.

It wasn’t a struggle for independence. And it wasn’t a fight for liberty. For the sterile Pavement Ant worker, all the exertion and all the hazard of assuming the role of a soldier had but one purpose—to raise her sisters and become an aunt. Long live the queen.