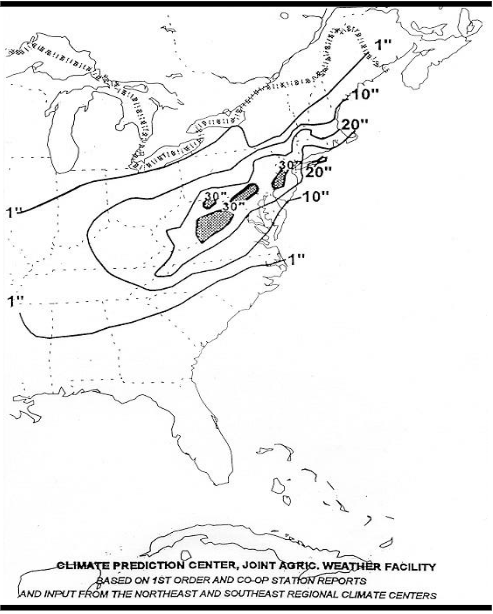

It all started rather innocently as a typically cold early January with sheets of ice covering the river and with soils on the lands in the remainder of the lower Susquehanna watershed frozen solid. Then came the “Blizzard of ’96”, blanketing much of the valley with between 20 and 30 inches of wind-driven snow.

In affected areas of Pennsylvania, Governor Tom Ridge closed all state roads for the duration of the snowfall event. Many would remain closed for much of the following week as drifting hampered exhaustive efforts to get impassable routes open.

Just as the recovery entered its second week, a change in the weather pattern took hold as milder air and spring-like rains hastened the melt. Clogged by snow often several feet in depth, storm sewer inlets and other drainage features failed to collect the runoff. Street and urban flooding became widespread. Some buildings, particular those with large flat roofs, experienced structural damage due to any remaining snow soaking up the additional weight of the rain. As local creeks swelled to stain snowy meadows brown, attention shifted to the icy river.

On the Susquehanna, rising waters started moving ice into accumulating piles of car-sized chunks behind dams and at choke points along the river’s course. During warmer weather, stream gauges provide a depth of water reference known as a stage (measured in feet) that corresponds to a rate of flow passing the gauge site (measured in cubic feet per second). On occasions when ice and debris block river channels during winter, these readings can fluctuate wildly and the relationship between stage and flow can become dubious. When the water is running ice-free at Harrisburg for example, a gauge reading of about 11.1 feet is indicated when the river flow rate is approximately 162,000 cubic feet per second. But due to its impact on the capability of the river channels to pass water, the presence of slow-moving and jammed ice can cause rapid and sometimes unpredictable variations in gauge readings, even when the flow rate remains steady. Impaired by an ice jam at the gauging station or just downriver, a flow of 162,000 cubic feet per second could lead to a stage measurement significantly higher than 11.1 feet, and the area of adjacent floodplain inundated by rising waters will increase to a corresponding degree. Conversely, a jam upstream of the gauging station could cause the reading to drop below 11.1 feet—at least temporarily—then look out, a dangerous surge could be forthcoming!

At Harrisburg, the ice jam behind the Dock Street Dam in January, 1996, caused devastating flooding in the city’s Shipoke neighborhood, on City Island, and in low-lying areas along the river’s west shore.

Downriver at Conewago Falls, ice jams behind the York Haven Dam and at several choke points within the riverine archipelago that extends from Haldeman Island to Haldeman Riffles in Lancaster County would be relieved as the river crested there during the afternoon of January 21st. The following photograph accurately relates the scene, minus the stench of mammalian feces and petroleum emanating from the polluted water of course.