Despite being located in an urbanized downtown setting, blustery weather in recent days has inspired a wonderful variety of small birds to visit the garden here at the susquehannawildlife.net headquarters to feed and refresh. For those among you who may enjoy an opportunity to see an interesting variety of native birds living around your place, we’ve assembled a list of our five favorite foods for wild birds.

The selections on our list are foods that provide supplemental nutrition and/or energy for indigenous species, mostly songbirds, without sustaining your neighborhood’s non-native European Starlings and House Sparrows, mooching Eastern Gray Squirrels, or flock of ecologically destructive hand-fed waterfowl. We’ve included foods that aren’t necessarily the cheapest but are instead those that are the best value when offered properly.

Number 5

Raw Beef Suet

In addition to rendered beef suet, manufactured suet cakes usually contain seeds, cracked corn, peanuts, and other ingredients that attract European Starlings, House Sparrows, and squirrels to the feeder, often excluding woodpeckers and other native species from the fare. Instead, we provide raw beef suet.

Because it is unrendered and can turn rancid, raw beef suet is strictly a food to be offered in cold weather. It is a favorite of woodpeckers, nuthatches, and many other species. Ask for it at your local meat counter, where it is generally inexpensive.

Number 4

Niger (“Thistle”) Seed

Niger seed, also known as nyjer or nyger, is derived from the sunflower-like plant Guizotia abyssinica, a native of Ethiopia. By the pound, niger seed is usually the most expensive of the bird seeds regularly sold in retail outlets. Nevertheless, it is a good value when offered in a tube or wire mesh feeder that prevents House Sparrows and other species from quickly “shoveling” it to the ground. European starlings and squirrels don’t bother with niger seed at all.

Niger seed must be kept dry. Mold will quickly make niger seed inedible if it gets wet, so avoid using “thistle socks” as feeders. A dome or other protective covering above a tube or wire mesh feeder reduces the frequency with which feeders must be cleaned and moist seed discarded. Remember, keep it fresh and keep it dry!

Number 3

Striped Sunflower Seed

Striped sunflower seed, also known as grey-striped sunflower seed, is harvested from a cultivar of the Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), the same tall garden plant with a massive bloom that you grew as a kid. The Common Sunflower is indigenous to areas west of the Mississippi River and its seeds are readily eaten by many native species of birds including jays, finches, and grosbeaks. The husks are harder to crack than those of black oil sunflower seed, so House Sparrows consume less, particularly when it is offered in a feeder that prevents “shoveling”. For obvious reasons, a squirrel-proof or squirrel-resistant feeder should be used for striped sunflower seed.

Number 2

Mealworms

Mealworms are the commercially produced larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor. Dried or live mealworms are a marvelous supplement to the diets of numerous birds that might not otherwise visit your garden. Woodpeckers, titmice, wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, and bluebirds are among the species savoring protein-rich mealworms. The trick is to offer them without European Starlings noticing or having access to them because European Starlings you see, go crazy over a meal of mealworms.

Number 1

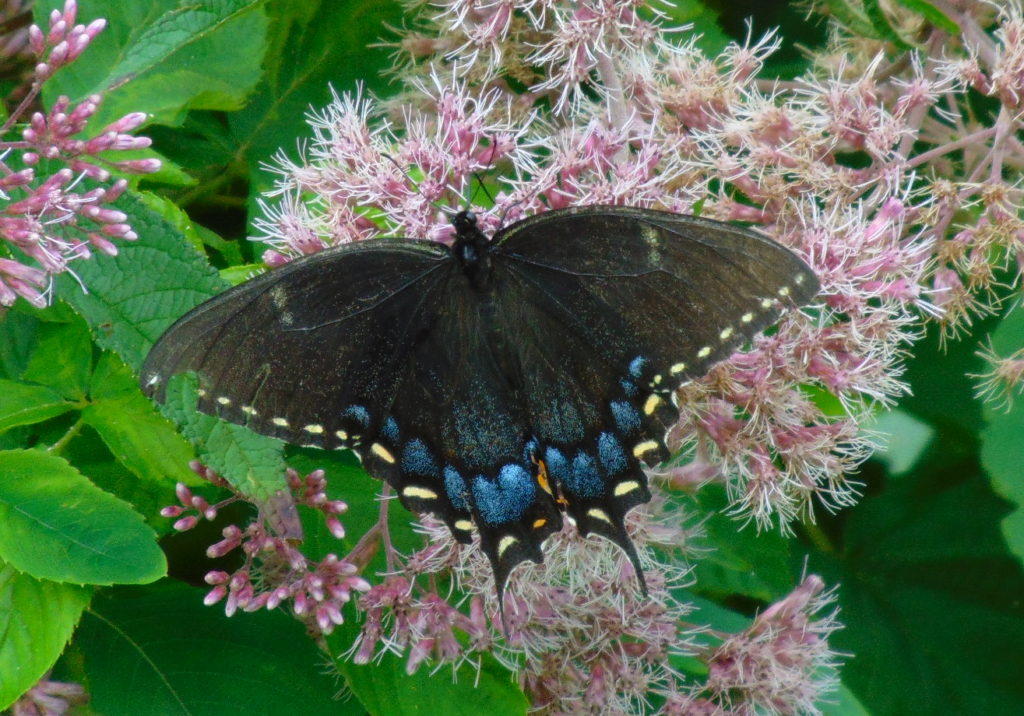

Food-producing Native Shrubs and Trees

The best value for feeding birds and other wildlife in your garden is to plant food-producing native plants, particularly shrubs and trees. After an initial investment, they can provide food, cover, and roosting sites year after year. In addition, you’ll have a more complete food chain on a property populated by native plants and all the associated life forms they support (insects, spiders, etc.).

Your local County Conservation District is having its annual spring tree sale soon. They have a wide selection to choose from each year and the plants are inexpensive. They offer everything from evergreens and oaks to grasses and flowers. You can afford to scrap the lawn and revegetate your whole property at these prices—no kidding, we did it. You need to preorder for pickup in the spring. To order, check their websites now or give them a call. These food-producing native shrubs and trees are by far the best bird feeding value that you’re likely to find, so don’t let this year’s sales pass you by!