A sixteen year-old skinny kid driving a Ford Pinto on a Saturday afternoon in late March, 1979, might be perceived by some observers as a metaphor for the accident at Three Mile Island on that same day. When experiencing a rear-end collision, the fuel tank on these little compact cars had been known to explode, sometimes with fatal consequences. They quickly gained a reputation as a deadly hazard on the highway. Despite a recall and engineering fix to prevent the fuel tank from failing, the Pinto remained cursed, and it was henceforth looked upon as a dangerous creation of man that best be avoided if you wished to remain in good health.

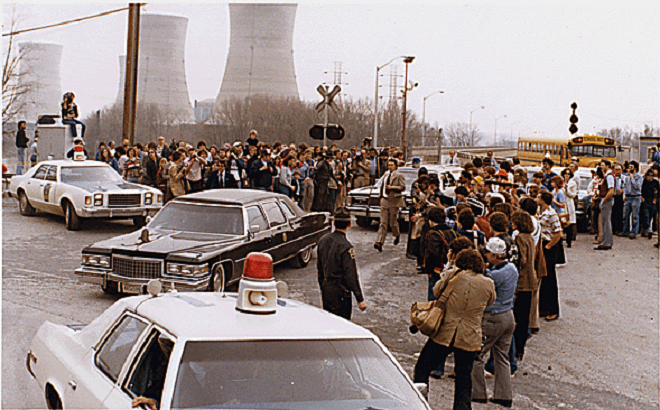

For a sixteen year-old, a Pinto functioned just fine as a frugal form of transportation. So in a hideous limey-yellow one, a kid showed up at the Three Mile Island Observation Center to have a look around. There, hundreds of photographers, reporters, and journalists had gathered to try for their angle on the latest news from the accident scene. Cars and news vans lined the state road, Pennsylvania Route 441, in front of the facility. Anything that moved was photographed and interviewed. The story of the day, March 31, 1979, was the impending explosion of the hydrogen gas bubble in the Unit 2 reactor. It was the sensation that they had waited for.

By Saturday, the N.R.C. was growing concerned about the potential of a hydrogen explosion within the Unit 2 reactor. Hydrogen was formed early in the accident when hot steam in the high-temperature core reacted with the zirconium alloy in the fuel rod cladding and produced primarily zirconium dioxide and hydrogen gas. Some of this gas had been vented into the reactor containment building. There, it mixed with atmospheric oxygen and ignited when a block valve switch was operated during the late morning of day one. Operators recalled hearing a “whooshing” sound just after flipping the switch. It is believed they did not really hear the explosion or burn-off of the gas, but rather the activation of a water spray system in the building in response to it.

The N.R.C. learned on Friday of this event that had occurred two days earlier. Harold Denton wanted to know if radiolysis of water inside the reactor was producing additional hydrogen and, more critically, oxygen. Many in the N.R.C. were convinced by their calculations that enough oxygen could be produced in the coming days to make the existing hydrogen bubble explosive. Denton wanted to know for sure, and ordered a team to enlist outside help to determine a timeline for this radiolysis. He also assigned a team to determine the parameters and details for a possible explosion.

Meanwhile, this story had gone public. Upon hearing the words “nuclear” and “explosion” together in news reports, the memories of old Civil Defense promotions came back to haunt local residents, and the nation. For many, the horrific image of a nuclear explosion had been projected into their perception of the accident. An explosion similar to an atomic bomb was not possible in the reactors of the type used for energy production in the United States, but few sleep well with visions of mushroom clouds dancing in their heads. For those on the fence deciding whether to stay or go, this was it, the last straw. In response to these broadcasts, more residents left the lower Susquehanna region on Saturday. As they went out, press personnel moved in, many setting up camp at the Three Mile Island Observation Center.

At 2:45 P.M., reporters at N.R.C. headquarters in Bethesda were told that a 10 to 20 mile evacuation might be necessary as a precaution if the decision was made to attempt to force the hydrogen bubble out of the reactor.

An Associated Press story went public at 8:23 P.M. quoting N.R.C. officials as saying that the hydrogen bubble could explode spontaneously.

This information kept local Civil Defense personnel up through the night answering phone calls from the worried residents who remained in their homes. They wanted to know what to do, but the local offices and P.E.M.A. were getting very little advice from the Lieutenant Governor’s and Governor’s offices. The state B.R.P. was still providing them with radiation information, but beyond that, Civil Defense offices were on their own for the night.

Harold Denton, being informed that President Carter was coming to Three Mile Island the next day, wanted things clarified. He told his deputy Victor Stello, Jr. to solicit sources outside the N.R.C. on the oxygen issue. Stello had fielded a call from the White House at about 9:00 P.M.. In response to the A.P. story, he told a presidential aide that he did not share the concern of others at the N.R.C. regarding the production of oxygen in the reactor. He and some engineers at Babcock & Wilcox, designers of the reactor, were among the few who shared this opinion. (Also, engineers at Babcock & Wilcox analyzing the effects of an explosion, should one occur, were confident that water and steam, if maintained in the pressurized reactor containment vessel, would reduce the pressure of an explosion to within the capabilities of the vessel to contain it.)

On Sunday morning, April 1, 1979, Victor Stello made his case to Harold Denton explaining why he thought there would be no hydrogen explosion in the Unit 2 reactor. He told Denton that pressurized water reactors like TMI-2 routinely have free hydrogen circulating in the coolant. The majority of oxygen produced by radiolysis would bind with this hydrogen and simply make more water.

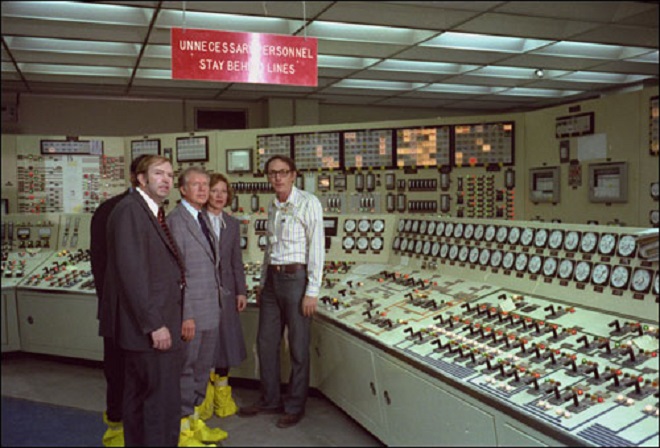

Just minutes before the President landed at the Air National Guard facility at Harrisburg International Airport at 1:00 P.M., the N.R.C.’s Joseph Hendrie and Roger Mattson, who had been researching the explosion question, arrived at a hangar there to present their case to Denton.

Quoted in the “Report of the President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island”, Mattson described the scene:

“…And Stello tells me I am crazy, that he doesn’t believe it, and he thinks we’ve made an error in the rate of calculation…Stello says we’re nuts and poor Harold is there, he’s got to meet with the President in 5 minutes and tell it like it is. And here he is. His two experts are not together. One comes armed to the teeth with all these national laboratories and Navy reactor people and high faluting PhDs around the country, saying this is what it is and this is the best summary. And his other (the operating reactors division) director saying, “I don’t believe it. I can’t prove it yet, but I don’t believe it. I think it’s wrong.”…”

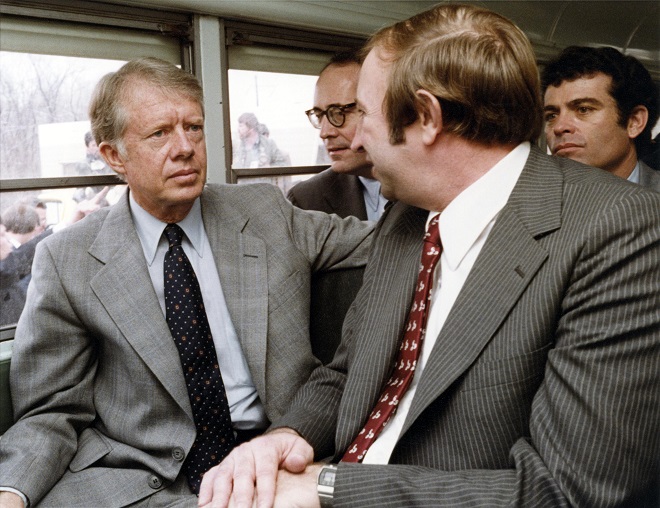

President Jimmy Carter was no stranger to nuclear reactors, or reactor accidents for that matter. A 1947 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, Carter eventually worked his way into Captain (later Admiral) Hyman Rickover’s nuclear command. In 1952, Rickover (known as the father of the Nuclear Navy) ordered the 28 year-old Lieutenant Carter, then assigned to the Naval Reactors Branch at the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, to the scene of a partial meltdown of a research reactor at Chalk River Laboratories in Ontario, Canada.

There, Carter led a team of 23 men. Their job was to shut down and dismantle the damaged reactor. They built a mock-up of the reactor on a tennis court and practiced taking turns performing the tasks to complete the job. This model would be used to track the progress of the project in the actual reactor. When a bolt, nut, or other part was removed in the real reactor core, it would be removed from the model as well.

Following these preparations, men suited up in protective gear and were lowered into the reactor, one man at a time, to do the work. Each man in the rotation was permitted to be in the reactor for only ninety seconds, then he was hoisted back out. During every one of these short journeys to the core, each worker, including Carter, received a dose equivalent to a year’s worth of allowable radiation today. Carter’s urine was radioactive for six months afterward.

President Carter’s earlier experiences in Rickover’s Navy, particularly at Chalk River, gave him exceptional familiarity with conditions arising from the accident at Three Mile Island in 1979.

Following the briefing of the President and Governor, Stello, Hendrie, and Mattson went back to the N.R.C.’s temporary office to try to rectify the oxygen and explosion problem. After consulting with some additional outside sources, including Westinghouse and General Electric, they had the answer. The hydrogen bubble would NOT explode. It was 3:00 P.M.

At just before 4:00 P.M., there was a new push from the N.R.C. in Bethesda to start an evacuation within two miles of the plant. Chairman Hendrie informed them—there is NO danger of an explosion. The teams in Bethesda would find concurrence with Stello, Hendrie, and Mattson by later that evening. On Monday, the N.R.C. trickled out the good news, but would not outright admit that their calculation errors had caused a near panic. Instead, they claimed that they had been a little too conservative in their estimates.

Shortly following the President’s visit, or during it, the hydrogen bubble began dissipating. The public wasn’t made aware of it until the following day, Monday, April 2. By then, operators for the utility reported that it was nearly gone. No direct action had been taken to get rid of the bubble, its disappearance was mysterious, yet welcome.

Nobody knows how many people evacuated the lower Susquehanna valley during the accident. It is generally believed that over 100,000 left for at least the weekend. Some communities, such as Goldsboro, a small town overlooking Three Mile Island’s reactors from the York County side of the Susquehanna, may have experienced evacuation rates approaching ninety percent. In the majority of areas more distant from the plant, the rate was well below fifty percent. Most of those who left their homes began returning as schools reopened during the mid-week.

During that first weekend, the press was angling to get officials to speculate on the probability of the occurrence of a catastrophic core meltdown. No one had realized that the meltdown had already happened, on day one. It was determined in 1987 that in excess of half of the more than 100 tons of uranium oxide fuel had melted during that first morning. In 1989, 20 tons of molten fuel was discovered to have flowed to the bottom of the reactor vessel and solidified into a slag-like mass there. Fortunately, Unit 2’s pressurized reactor vessel had kept the catastrophic core meltdown contained within its five-inch-thick steel structure.

Crews on Three Mile Island worked faithfully to manage gases and continue the cooling of the reactor core. Cold shutdown of the reactor (reduction of temperatures to below the atmospheric boiling point of water) would take another week, the full cleanup and de-fueling would take more than a decade. Unit 2 was placed in monitored storage in 1993, and will be fully decommissioned simultaneously with the Unit 1 reactor when the latter is permanently taken out of service.

On the day of his visit to Three Mile Island, President Carter signed executive orders activating the Federal Emergency Management Agency (F.E.M.A.), a new entity formed to house Civil Defense and disaster preparedness, with the latter of the two becoming the greater focus of its mission.

Forty years after his visit to Three Mile Island, Jimmy Carter, at age 94 ½ years, had become the longest-lived President in American history. We wish he and Rosalynn many more happy years.

Finally, what shall we think of the risky travels of a sixteen year-old? Was the bigger hazard the act of being inside a Ford Pinto while driving to Three Mile Island on Saturday, March 31, 1979, or was it the act of being at Three Mile Island itself on that afternoon? We’ll let you decide.

SOURCES

Forman, Paul, and Sherman, Roger. 2004. Three Mile Island: The Inside Story. Web presentation based upon Smithsonian National Museum of American History exhibit, as accessed March 28, 2019. https://americanhistory.si.edu/tmi/index.htm

Kemeny, John G., et al. 1979. Report of the President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island; The Need for Change: The Legacy of TMI. U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Milnes, Arthur. January 28, 2009. “When Jimmy Carter Faced Radioactivity Head-on”. The Ottawa Citizen.