It was forty years ago today. The civics teacher had a hook on stick, and he was under orders to use it. He was trying his best to draw the water-stained paper blinds down over the tall old single-pane glass windows that covered the length of the outer wall of his west-facing room. You understand, this was not something he was doing of his own accord. He was a veteran educator, one of those teaching the offspring of his students from a previous generation. He was no tyrant merely wanting to deny his pupils the distractions of a beautiful spring day outdoors. He was ordered by the coffee cup brigade in the front office to close the windows and draw the shades. The safety of the students is at stake!

As his third class of the day entered the room, the instructor enlisted the help of a couple of taller students to try to get some of those stubborn window coverings pulled down. No luck. Class would commence with blinds up, down, and in between. Today’s topic: the dangers of nuclear energy. As usual, it was something of an open discussion of current events. All points of view were encouraged.

Few noticed the town fire siren howling away during the first minutes of the oratory. That happened every once in a while, so it wasn’t so remarkable. The class transformed from debate and dialog to a practical demonstration a little while later when fire trucks began circulating through the streets near the school broadcasting muffled incoherent warnings of some sort to the residents of adjacent neighborhoods.

Within moments there was clamor in the hallways as several students were banging locker doors and making off with their wares. Soon the old classroom phone that hung as a decoration on the wall near the doorway began making an obnoxious noise. What does this mean? What should we do? It never made a sound before. The dedicated educator walked over and picked up the receiver. He timidly said, “Hello?” He listened carefully, acknowledging the caller from time to time, then he said, “O.K.” After hanging up the little-used device, he walked over to a startled girl and simply told her to gather things and report to the office, one of her parents was here to pick her up.

The old sage walked back to the lectern and just stared around at the quiet faces in the room , not a word was said until the phone rang again. He looked over toward a skinny sixteen year-old kid, a late-bloomer, seated near the half-shaded windows and quietly said, “Mr. C—, you have duties to perform, don’t you?, you may leave.” Then he turned to answer the phone for the second time. The skinny kid departed the school building posthaste.

Since the beginning of the accident, operators of the Unit 2 reactor had been spending a considerable share of their time and effort coping with noncondensible gas in Unit 2’s coolant system. Not only was there growing concern that a build-up of Hydrogen around the top of the reactor core was preventing coolant from reaching the fuel assemblies, but gas was causing problems in other portions of the cooling system as well. One component in particular, a make-up tank used to store water that is used as needed to increase the volume of coolant in the primary cooling system, was of concern in the early morning hours of Friday, March 30, 1979. Its relief valve had activated at least once due to excessive pressure. Gauges read that gases had displaced all of the water from the tank.

Just before 7:00 A.M., operators decided to open a valve to purge the radioactive gases from the make-up tank into the waste gas decay tanks where it is collected and stored by design. The venting began at 7:10 A.M. Aware that a header leaks in this system, and that any leaked gas will enter the auxiliary building and be discharged to the atmosphere from its vent stack, a helicopter monitoring flight is requested to collect samples above the plant and its perimeter. Almost an hour into the venting process, at 8:01 A.M., a radiation reading of 1,200 millirems per hour (mr/hr) is measured 130 feet directly above the vent stack. A reading of only 14 mr/hr was taken along the boundary of the facility site. This was an expectable set of readings. During a short venting procedure involving the make-up tank on the previous day, a sampling flight measured 3,000 mr/hr fifteen feet above the stack .

Confident that they can now keep gas accumulation in the make-up tank under control by “puffing” it clear on a regular basis, and again having the ability to use the make-up tank to equalize coolant levels, the process is a success. The operators are on to the next step as they strive to get the reactor into a cold shutdown.

Friday’s memorable troubles resulted from a series of inaccurate reports of the 1,200 mr/hr reading taken above the auxiliary building vent stack. For the next ninety minutes, the 1,200 mr/hr figure shot like lightening through a chain of phone calls that left Three Mile Island and made its way through state-level and county-level offices and found smooth sailing through the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (N.R.C.) and landed right in the middle of meeting of the latter in Bethesda, Maryland.

But first, at 8:45 A.M., a Telex message arrives at the N.R.C.’s Incident Response Center:

“The seal return to the makeup tanks was causing excessive gas pressures in the makeup tank which was directed to the waste gas decay tanks which were full. The waste gas tanks were being released to the stack. Pennsylvania Civil Defense was being notified by Licensee.”

This errant message indicates that the highly radioactive contents of the waste gas decay tanks, which are NOT full, can be expected to vent from Three Mile Island with some regularity for the foreseeable future. At 9:00 A.M., the N.R.C.’s Lake Barrett carries the Telex into a meeting of the agency’s Executive Management Team (E.M.T.). Alarmed by the news, they ask Barrett to calculate what an off-site radiation dose might be with the anticipated releases. Ironically, Barrett arrives at a figure of 1,200 mr/hr for a person at the site boundary, a value exceeding the Environmental Protection Agency (E.P.A.) threshold for evacuation of sensitive persons. Within minutes, the E.M.T. receives a phone call from Karl Abraham, the N.R.C. press officer at Governor Richard Thornburgh’s office in Harrisburg. He’s on the speakerphone and wants to know if the reports of 1,200 mr/hr readings above the “cooling towers” are true. This is the first the E.M.T. has heard of the 1,200 mr/hr number at the site, and because it matches Barrett’s calculation for off-site releases from full waste gas decay tanks, they assume it to be an off-site number and forget that Abraham was asking a question. Following a discussion, Harold Denton, Director of Reactor Regulation, orders that a recommendation for evacuation out to ten miles in the direction of the plume be given to the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (P.E.M.A.), the state-level Civil Defense agency. This recommendation is delivered at 9:15 A.M. Unfortunately, the location of the 1,200 mr/hr reading was not verified beforehand.

In Harrisburg, Margaret Reilly of Pennsylvania’s Bureau of Radiation Protection (B.R.P.) was trying to verify the N.R.C.’s reasons for the evacuation recommendation. There was some ire because P.E.M.A. received the recommendation instead of the B.R.P., or, better yet, Governor Thornburgh himself. Information available to Pennsylvania agencies showed no reason to evacuate.

Dutifully acting on the N.R.C.’s recommendation, the state notifies Dauphin County Civil Defense, telling them to expect an evacuation order from the Governor within five minutes. The mild temperatures on this Friday were due to a steady wind from the southwest, putting communities in Dauphin County within any possible plume from the Three Mile Island Unit 2 facility. It appeared that communities in Dauphin County, including the city of Harrisburg, would comprise the majority of the evacuation zone. Fire companies, municipal officials, local Civil Defense directors, and others were alerted. Announcements on Harrisburg’s WHP radio advised citizens within five miles of T.M.I. to make preparations and gather supplies for a possible evacuation. The cat was out of the bag.

Governor Thornburgh was very cautious, possessing an understanding of the risks to the public that an evacuation order could cause. He would later be quoted, “In Pennsylvania, P.E.M.A.’s role is to manage the emergency, not to recommend evacuation. P.E.M.A. mentality (during the T.M.I.-2 accident) was akin to being all dressed up with no place to go—leaning forward in the trenches. We had to be careful about that attitude.” Thornburgh knew that ordering an evacuation meant moving patients in health care facilities, possibly at great risk to them. He knew too, that evacuation meant putting helmets in the street—the National Guard.

The Bureau of Radiation Protection had checked the site and conferred with the N.R.C. in Bethesda and was convinced that an evacuation was not necessary. Because of the public broadcasts, phone lines were jammed, so nuclear engineers from B.R.P. are hurriedly en route to the Governor’s office and P.E.M.A. to deliver the facts in person. It’s 9:45 A.M.

At the same time in Bethesda, the E.M.T. had learned that the 1,200 mr/hr reading was not from off-site, but from directly above the vent stack. They were also made aware that the venting had not come from the waste gas decay tanks, but from the make-up tank. And finally, they learned that the waste gas decay tanks were not full, but were accepting gases from the make-up tank as designed. By 10:00 A.M., they rescinded their evacuation order—about the same time that Governor Thornburgh countermanded it.

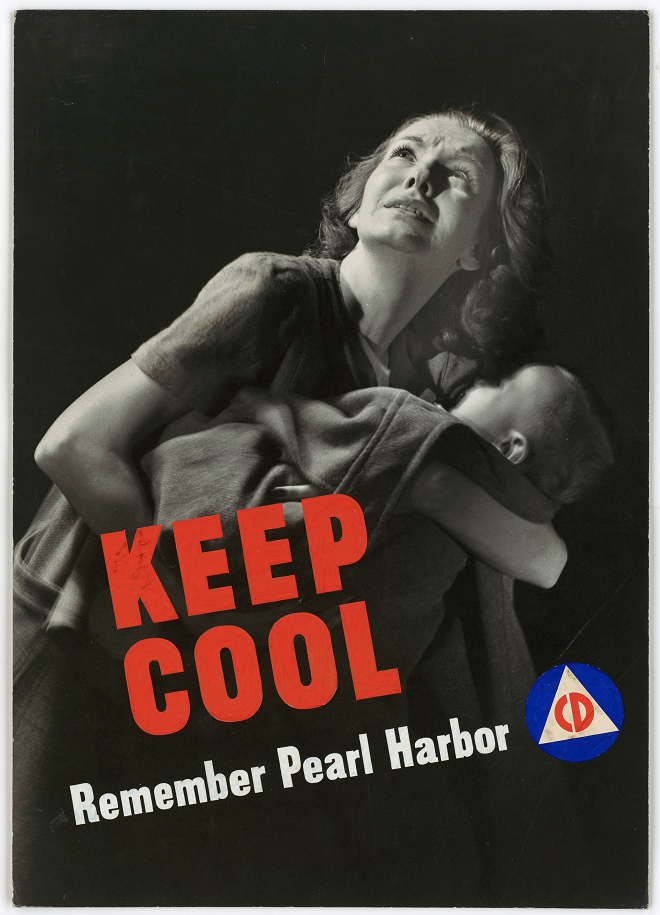

Too late. By this time people were getting out of town. Schools were overwhelmed as parents showed up to pull their children out of class, one by one at first, then in droves. Sirens were sounding. Broadcasts were telling people to close blinds and windows and remain indoors. The Three Mile Island Unit 2 accident was now the biggest news event in the nation.

Governor Thornburg went on WHP radio at 10:25 A.M. to broadcast a message to residents, attempting to rectify some of the contradictions of the morning. Within the hour, President Carter would call the Governor and assure him of the White House’s full support. He told the Governor that he was sending Harold Denton to the scene forthwith. Denton was to “take charge of the site on behalf of the federal government”.

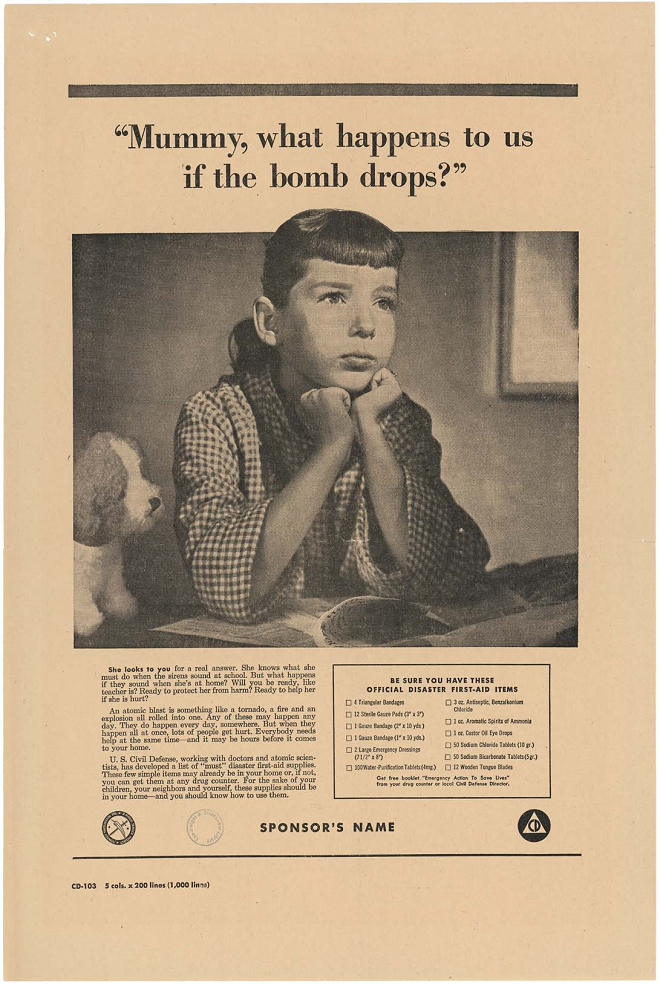

At local Civil Defense offices in the lower Susquehanna valley, there was a continuous flow of telephone calls from concerned citizens, some of them very frightened. They wanted to know what to do. The ball was rolling, and people with families were becoming more and more inclined to leave.

A skinny sixteen year-old volunteer walked into a community fire station in a small town about six miles from Three Mile Island at about 11:00 A.M. There, the town’s mayor and Civil Defense Director were conferring inside the “Civil Defense office”, a coat closet with a desk and ashtray. The phone was in the adjacent closet, which had more desks and ashtrays. The discussion centered around responsibilities for ordering an evacuation. Following the events at the federal and state level earlier in the morning, it was unclear who had the authority and responsibility to order an evacuation.

The scene was tense, the cigarette smoke was rolling out of the closet for hours as phone calls were made and the chain of command was clarified. Evacuation plans were being worked out in case they were needed. Moving patients from hospitals and nursing facilities was a particularly difficult planning challenge to be tackled. The cloud would persist as the chain smoking continued for the next couple of days. (And those plaid double-knit leisure suits with Flintstones neckties—wow!—it’s a good thing there were no photographs taken of this scene.)

Elsewhere inside the fire station, the sixteen year-old lad and some other volunteers collected the radiological monitoring supplies from the blue and white Civil Defense rescue truck. After gathering some fresh batteries, they ventured outdoors and set up a small monitoring station. Lungs clouded by all the chain smoking inside could be clarified out there. Several metering devices were employed in an attempt to detect radiation. The crew remained at their post through late afternoon, keeping a sharp lookout for the fashion police and enjoying the balmy spring air. It was easy work and no radiation was detected.

Following further consultation with the N.R.C., the Governor held a press conference at 12:30 A.M. He advised pregnant women and pre-school age children to leave the area of a five-mile radius around Three Mile Island. He closed the schools and the few students still in the classrooms were on their way home—or to the mountains for an unscheduled spring holiday.

Harold Denton would arrive at Three Mile Island during the mid-afternoon. Denton found inadequate facilities and communications (no cellular telephone in 1979!) at the T.M.I. Observation Center building where other N.R.C. personnel had set up temporarily. This facility on the east shore of the Susquehanna overlooking the plant was now overrun by scores and soon hundreds of reporters, so Denton set up his base in a home offered by a Met-Ed employee just across the street. He set up his temporary office in the living room, complete with a direct line to the White House. Denton would have his work cut out for him; the hydrogen gas bubble was becoming an increasing concern and the press was storming over the possibility of a catastrophic meltdown. The situation was serious—there would be no BINGO in the fire halls this weekend.

Thanks Mr. H—, wherever you are!

SOURCES

Kemeny, John G., et al. 1979. Report of the President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island; The Need for Change: The Legacy of TMI. U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Rogovin, Mitchell, et al. 1980. Three Mile Island: A Report to the Commisssioners and the Public. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.