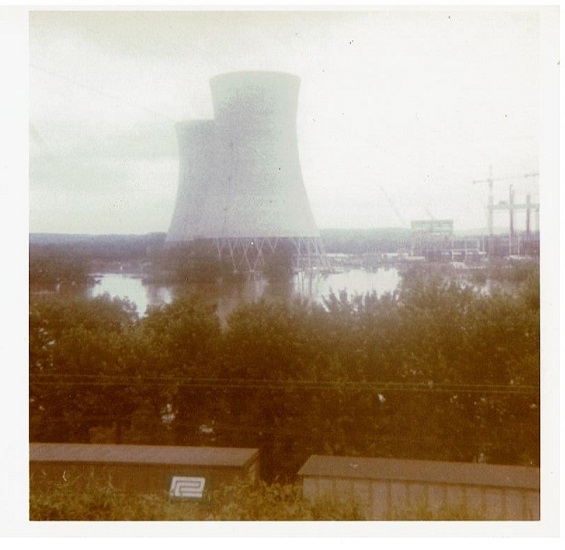

Fifty years ago this week, the remnants of Hurricane Agnes drifted north through the Susquehanna River basin as a tropical storm and saturated the entire watershed with wave after wave of torrential rains. The storm caused catastrophic flooding along the river’s main stem and along many major tributaries. The nuclear power station at Three Mile Island, then under construction, received its first major flood. Here are some photos taken during the climax of that flood on June 24, 1972. The river stage as measured just upstream of Three Mile Island at the Harrisburg gauge crested at 33.27 feet, more than 10 feet above flood stage and almost 30 feet higher than the stage at present. At Three Mile Island and Conewago Falls, the river was receiving additional flow from the raging Swatara Creek, which drains much of the anthracite coal region of eastern Schuylkill County—where rainfall from Agnes may have been the heaviest.

Pictures capture just a portion of the experience of witnessing a massive flood. Sometimes the sounds and smells of the muddy torrents tell us more than photographs can show.

Aside from the booming noise of the fuel tank banging along the rails of the south bridge, there was the persistent roar of floodwaters, at the rate of hundreds of thousands of cubic feet per second, tumbling through Conewago Falls on the downstream side of the island. The sound of the rapids during a flood can at times carry for more than two miles. It’s a sound that has accompanied the thousands of floods that have shaped the falls and its unique diabase “pothole rocks” using abrasives that are suspended in silty waters after being eroded from rock formations in the hundreds of square miles of drainage basin upstream. This natural process, the weathering of rock and the deposition of the material closer to the coast, has been the prevailing geologic cycle in what we now call the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed since the end of the Triassic Period, more than two hundred million years ago.

More than the sights and sounds, it was the smell of the Agnes flood that warned witnesses of the dangers of the non-natural, man-made contamination—the pollution—in the waters then flowing down the Susquehanna.

Because they float, gasoline and other fuels leaked from flooded vehicles, storage tanks, and containers were most apparent. The odor of their vapors was widespread along not only along the main stem of the river, but along most of the tributaries that at any point along their course passed through human habitations.

Blended with the strong smell of petroleum was the stink of untreated excrement. Flooded treatment plants, collection systems overwhelmed by stormwater, and inundated septic systems all discharged raw sewage into the river and many of its tributaries. This untreated wastewater, combined with ammoniated manure and other farm runoff, gave a damaging nutrient shock to the river and Chesapeake Bay.

Adding to the repugnant aroma of the flood was a mix of chemicals, some percolated from storage sites along watercourses, and yet others leaking from steel drums seen floating in the river. During the decades following World War II, stacks and stacks of drums, some empty, some containing material that is very dangerous, were routinely stored in floodplains at businesses and industrial sites throughout the Susquehanna basin. Many were lifted up and washed away during the record-breaking Agnes flood. Still others were “allowed” to be carried away by the malicious pigs who see a flooding stream as an opportunity to “get rid of stuff”. Few of these drums were ever recovered, and hundreds were stranded along the shoreline and in the woods and wetlands of the floodplain below Conewago Falls. There, they rusted away during the next three decades, some leaking their contents into the surrounding soils and waters. Today, there is little visible trace of any.

During the summer of ’72, the waters surrounding Three Mile Island were probably viler and more polluted than at any other time during the existence of the nuclear generating station there. And little, if any of that pollution originated at the facility itself.

The Susquehanna’s floodplain and water quality issues that had been stashed in the corner, hidden out back, and swept under the rug for years were flushed out by Agnes, and she left them stuck in the stinking mud.