Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

Photo of the Day

They’re Here

The Magi have arrived. Emanating from the shadows of a nearby forest, you may hear the endless drone of what sounds like an extraterrestrial craft. Then you get your first look at those beady red eyes set against a full suit of black armor—out of this world. The Magicicada are here at last.

If you go out and about to observe Periodical Cicadas, keep an eye open for these species too…

Forest vs. Woodlot

Let’s take a quiet stroll through the forest to have a look around. The spring awakening is underway and it’s a marvelous thing to behold. You may think it a bit odd, but during this walk we’re not going to spend all of our time gazing up into the trees. Instead, we’re going to investigate the happenings at ground level—life on the forest floor.

There certainly is more to a forest than the living trees. If you’re hiking through a grove of timber getting snared in a maze of prickly Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) and seeing little else but maybe a wild ungulate or two, then you’re in a has-been forest. Logging, firewood collection, fragmentation, and other man-made disturbances inside and near forests take a collective toll on their composition, eventually turning them to mere woodlots. Go enjoy the forests of the lower Susquehanna valley while you still can. And remember to do it gently; we’re losing quality as well as quantity right now—so tread softly.

October Transition

Thoughts of October in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed bring to mind scenes of brilliant fall foliage adorning wooded hillsides and stream courses, frosty mornings bringing an end to the growing season, and geese and other birds flying south for the winter.

The autumn migration of birds spans a period equaling nearly half the calendar year. Shorebirds and Neotropical perching birds begin moving through as early as late July, just as daylight hours begin decreasing during the weeks following their peak at summer solstice in late June. During the darkest days of the year, those surrounding winter solstice in late December, the last of the southbound migrants, including some hawks, eagles, waterfowl, and gulls, may still be on the move.

During October, there is a distinct change in the list of species an observer might find migrating through the lower Susquehanna valley. Reduced hours of daylight and plunges in temperatures—particularly frost and freeze events—impact the food sources available to birds. It is during October that we say goodbye to the Neotropical migrants and hello to those more hardy species that spend their winters in temperate climates like ours.

The need for food and cover is critical for the survival of wildlife during the colder months. If you are a property steward, think about providing places for wildlife in the landscape. Mow less. Plant trees, particularly evergreens. Thickets are good—plant or protect fruit-bearing vines and shrubs, and allow herbaceous native plants to flower and produce seed. And if you’re putting out provisions for songbirds, keep the feeders clean. Remember, even small yards and gardens can provide a life-saving oasis for migrating and wintering birds. With a larger parcel of land, you can do even more.

Stray Butterflies

A special message from your local Chinese Mantis (Tenodera sinensis).

Hey you! Yes, you. I pray you’re paying attention to what’s flying around out there, otherwise it’ll all pass you by.

This summer’s hot humid breezes from the south have not only carried swarms of dragonflies into the lower Susquehanna valley, but butterflies too.

So check out these extravagant visitors from south of the Mason-Dixon Line—before my appetite gets the better of me.

There you have it. Get out there and have a look around. These species won’t be active much longer. In just a matter of weeks, our migratory butterflies, including Monarchs, will be heading south and our visiting strays will either follow their lead or risk succumbing to frosty weather.

For more photographs of butterflies, be sure to click the “Butterflies” tab at the top of the page. We’re adding more as we get them.

Clean Slate for 2020

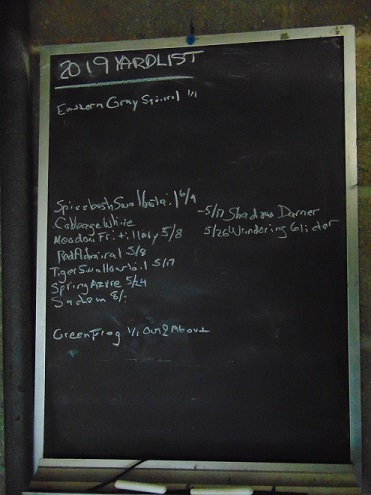

Inside the doorway that leads to your editor’s 3,500 square foot garden hangs a small chalkboard upon which he records the common names of the species of birds that are seen there—or from there—during the year. If he remembers to, he records the date when the species was first seen during that particular year. On New Year’s Day, the results from the freshly ended year are transcribed onto a sheet of notebook paper. On the reverse, the names of butterflies, mammals, and other animals that visited the garden are copied from a second chalkboard that hangs nearby. The piece of paper is then inserted into a folder to join those from previous New Year’s Days. The folder then gets placed back into the editor’s desk drawer beneath a circular saw blade and an old scratched up set of sunglasses—so that he knows exactly where to find it if he wishes to.

A quick glance at this year’s list calls to mind a few recollections.

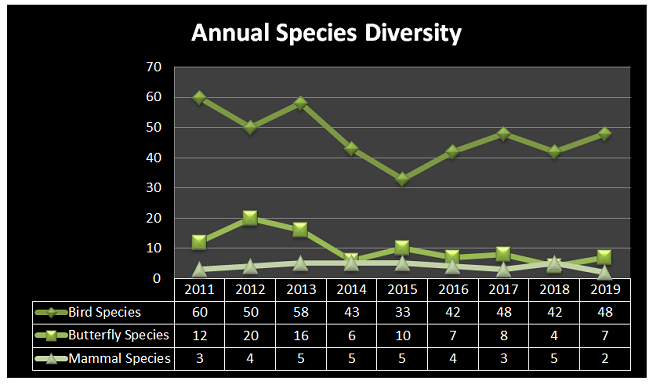

Before putting the folder back into the drawer for another year, the editor decided to count up the species totals on each of the sheets and load them into the chart maker in the computer.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

Despite the habitat improvements in the garden, the trend is apparent. Bird diversity has not cracked the 50 species mark in 6 years. Despite native host plants and nectar species in abundance, butterfly diversity has not exceeded 10 species in 6 years.

It appears that, at the very least, the garden habitat has been disconnected from the home ranges of many species by fragmentation. His little oasis is now isolated in a landscape that becomes increasingly hostile to native wildlife with each passing year. The paving of more parking areas, the elimination of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous growth from the large number of rental properties in the area, the alteration of the biology of the nearby stream by hand-fed domestic ducks, light pollution, and the outdoor use of pesticides have all contributed to the separation of the editor’s tiny sanctuary from the travel lanes and core habitats of many of the species that formerly visited, fed, or bred there. In 2019, migrants, particularly “fly-overs”, were nearly the only sightings aside from several woodpeckers, invasive House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), and hardy Mourning Doves. Even rascally European Starlings became sporadic in occurrence—imagine that! It was the most lackluster year in memory.

If habitat fragmentation were the sole cause for the downward trend in numbers and species, it would be disappointing, but comprehendible. There would be no cause for greater alarm. It would be a matter of cause and effect. But the problem is more widespread.

Although the editor spent a great deal of time in the garden this year, he was also out and about, traveling hundreds of miles per week through lands on both the east and the west shores of the lower Susquehanna. And on each journey, the number of birds seen could be counted on fingers and toes. A decade earlier, there were thousands of birds in these same locations, particularly during the late summer.

In the lower Susquehanna valley, something has drastically reduced the population of birds during breeding season, post-breeding dispersal, and the staging period preceding autumn migration. In much of the region, their late-spring through summer absence was, in 2019, conspicuous. What happened to the tens of thousands of swallows that used to gather on wires along rural roads in August and September before moving south? The groups of dozens of Eastern Kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus) that did their fly-catching from perches in willows alongside meadows and shorelines—where are they?

Several studies published during the autumn of 2019 have documented and/or predicted losses in bird populations in the eastern half of the United States and elsewhere. These studies looked at data samples collected during recent decades to either arrive at conclusions or project future trends. They cite climate change, the feline infestation, and habitat loss/degradation among the factors contributing to alterations in range, migration, and overall numbers.

There’s not much need for analysis to determine if bird numbers have plummeted in certain Lower Susquehanna Watershed habitats during the aforementioned seasons—the birds are gone. None of these studies documented or forecast such an abrupt decline. Is there a mysterious cause for the loss of the valley’s birds? Did they die off? Is there a disease or chemical killing them or inhibiting their reproduction? Is it global warming? Is it Three Mile Island? Is it plastic straws, wind turbines, or vehicle traffic?

The answer might not be so cryptic. It might be right before our eyes. And we’ll explore it during 2020.

In the meantime, Uncle Ty and I going to the Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg. You should go too. They have lots of food there.

Some Autumn Insects

With autumn coming to a close, let’s have a look at some of the fascinating insects (and a spider) that put on a show during some mild afternoons in the late months of 2019.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.

Noxious Benefactor

It’s sprayed with herbicides. It’s mowed and mangled. It’s ground to shreds with noisy weed-trimmers. It’s scorned and maligned. It’s been targeted for elimination by some governments because it’s undesirable and “noxious”. And it has that four letter word in its name which dooms the fate of any plant that possesses it. It’s the Common Milkweed, and it’s the center of activity in our garden at this time of year. Yep, we said milk-WEED.

Now, you need to understand that our garden is small—less than 2,500 square feet. There is no lawn, and there will be no lawn. We’ll have nothing to do with the lawn nonsense. Those of you who know us, know that the lawn, or anything that looks like lawn, are through.

Anyway, most of the plants in the garden are native species. There are trees, numerous shrubs, some water features with aquatic plants, and filling the sunny margins is a mix of native grassland plants including Common Milkweed. The unusually wet growing season in 2018 has been very kind to these plants. They are still very green and lush. And the animals that rely on them are having a banner year. Have a look…

We’ve planted a variety of native grassland species to help support the milkweed structurally and to provide a more complete habitat for Monarch butterflies and other native insects. This year, these plants are exceptionally colorful for late-August due to the abundance of rain. The warm season grasses shown below are the four primary species found in the American tall-grass prairies and elsewhere.

There was Monarch activity in the garden today like we’ve never seen before—and it revolved around milkweed and the companion plants.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

Living in the Shadows

They get a touch of it here, and a sparkle or two there. Maybe, for a couple of hours each day, the glorious life-giving glow of the sun finds an opening in the canopy to warm and nourish their leaves, then the rays of light creep away across the forest floor, and it’s shade for the remainder of the day.

The flowering plants which thrive in the understory of the Riparian Woodlands often escape much notice. They gather only a fraction of the daylight collected by species growing in full exposure to the sun. Yet, by season’s end, many produce showy flowers or nourishing fruits of great import to wildlife. While light may be sparingly rationed through the leaves of the tall trees overhead, moisture is nearly always assured in the damp soils of the riverside forest. For these plants, growth is slow, but continuous. And now, it’s show time.

So let’s take a late-summer stroll through the Riparian Woodlands of Conewago Falls, minus the face full of cobwebs, and have a look at some of the strikingly beautiful plants found living in the shadows.

SOURCES

Long, David; Ballentine, Noel H.; and Marks, James G., Jr. 1997. Treatment of Poison Ivy/Oak Allergic Contact Dermatitis With an Extract of Jewelweed. American Journal of Contact Dermatitis. 8(3): pp. 150-153.

Newcomb, Lawrence. 1977. Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide. Little, Brown and Company. Boston, Massachusetts.

Beauties

It’s tough being good-looking and liked by so many. You’ve got to watch out, because popularity makes you a target. Others get jealous and begin a crusade to have you neutralized and removed from the spotlight. They’ll start digging to find your little weaknesses and flaws, then they’ll exploit them to destroy your reputation. Next thing you know, people look at you as some kind of hideous scoundrel.

Today, bright afternoon sunshine and a profusion of blooming wildflowers coaxed butterflies into action. It was one of those days when you don’t know where to look first.

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) has a bad reputation. Not native to the Americas, this prolific seed producer began spreading aggressively into many wetlands following its introduction. It crowds out native plant species and can have a detrimental impact on other aquatic life. Stands of loosestrife in slow-moving waters can alter flows, trap sediment, and adversely modify the morphology of waterways. Expensive removal and biological control are often needed to protect critical habitat.

The dastardly Purple Loosestrife may have only two positive attributes. First, it’s a beautiful plant. And second, it’s popular; butterflies and other pollinators find it to be irresistible and go wild over the nectar.

Don’t you just adore the wonderful butterflies. Everybody does. Just don’t tell anyone that they’re pollinating those dirty filthy no-good Purple Loosestrife plants.

SOURCES

Brock, Jim P., and Kenn Kaufman. 2003. Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

Newcomb, Lawrence. 1977. Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide. Little, Brown and Company. Boston, Massachusetts.

The Dungeon

There’s something frightening going on down there. In the sand, beneath the plants on the shoreline, there’s a pile of soil next to a hole it’s been digging. Now, it’s dragging something toward the tunnel it made. What does it have? Is that alive?

We know how the system works, the food chain that is. The small stuff is eaten by the progressively bigger things, and there are fewer of the latter than there are of the former, thus the whole network keeps operating long-term. Some things chew plants, others devour animals whole or in part, and then there are those, like us, that do both. In the natural ecosystem, predators keep the numerous little critters from getting out of control and decimating certain other plant or animal populations and wrecking the whole business. When man brings an invasive and potentially destructive species to a new area, occasionally we’re fortunate enough to have a native species adapt and begin to keep the invader under control by eating it. It maintains the balance. It’s easy enough to understand.

Late summer days are marked by a change in the sounds coming from the forests surrounding the falls. For birds, breeding season is ending, so the males cease their chorus of songs and insects take over the musical duties. The buzzing calls of male “Annual Cicadas” (Neotibicen species) are the most familiar. The female “Annual Cicada” lays her eggs in the twigs of trees. After hatching, the nymphs drop to the ground and burrow into the soil to live and feed along tree roots for the next two to five years. A dry exoskeleton clinging to a tree trunk is evidence that a nymph has emerged from its subterranean haunts and flown away as an adult to breed and soon thereafter die. Flights of adult “Annual Cicadas” occur every year, but never come anywhere close to reaching the enormous numbers of “Periodical Cicadas” (Magicicada species). The three species of “Periodical Cicadas” synchronize their life cycles throughout their combined regional populations to create broods that emerge as spectacular flights once every 13 or 17 years.

For the adult cicada, there is danger, and that danger resembles an enormous bee. It’s an Eastern Cicada Killer (Specius speciosus) wasp, and it will latch onto a cicada and begin stinging while both are in flight. The stings soon paralyze the screeching, panicked cicada. The Cicada Killer then begins the task of airlifting and/or dragging its victim to the lair it has prepared. The cicada is placed in one of more than a dozen cells in the tunnel complex where it will serve as food for the wasp’s larvae. The wasp lays an egg on the cicada, then leaves and pushes the hole closed. The egg hatches in a several days and the larval grub is on its own to feast upon the hapless cicada.

Other species in the Solitary Wasp family (Sphecidae) have similar life cycles using specific prey which they incapacitate to serve as sustenance for their larvae.

The Solitary Wasps are an important control on the populations of their respective prey. Additionally, the wasp’s bizarre life cycle ensures a greater survival rate for its own offspring by providing sufficient food for each of its progeny before the egg beginning its life is ever put in place. It’s complete family planning.

The cicadas reproduce quickly and, as a species, seem to endure the assault by Cicada Killers, birds, and other predators. The Periodical Cicadas (Magicicada), with adult flights occurring as a massive swarm of an entire population every thirteen or seventeen years, survive as species by providing predators with so ample a supply of food that most of the adults go unmolested to complete reproduction. Stay tuned, 2021 is due to be the next Periodical Cicada year in the vicinity of Conewago Falls.

SOURCES

Eaton, Eric R., and Kenn Kaufman. 2007. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York.

S’more

The tall seed-topped stems swaying in a summer breeze are a pleasant scene. And the colorful autumn shades of blue, orange, purple, red, and, of course, green leaves on these clumping plants are nice. But of the multitude of flowering plants, Big Bluestem, Freshwater Cordgrass, and Switchgrass aren’t much of a draw. No self-respecting bloom addict is going out of their way to have a gander at any grass that hasn’t been subjugated and tamed by a hideous set of spinning steel blades. Grass flowers…are you kidding?

O.K., so you need something more. Here’s more.

Meet the Partridge Pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata). It’s an annual plant growing in the Riverine Grasslands at Conewago Falls as a companion to Big Bluestem. It has a special niche growing in the sandy and, in summertime, dry soils left behind by earlier flooding and ice scour. The divided leaves close upon contact and also at nightfall. Bees and other pollinators are drawn to the abundance of butter-yellow blossoms. Like the familiar pea of the vegetable garden, the flowers are followed by flat seed pods.

But wait, here’s more.

In addition to its abundance in Conewago Falls, the Halberd-leaved Rose Mallow (Hibiscus laevis) is the ubiquitous water’s edge plant along the free-flowing Susquehanna River for miles downstream. It grows in large clumps, often defining the border between the emergent zone and shore-rooted plants. It is particularly successful in accumulations of alluvium interspersed with heavier pebbles and stone into which the roots will anchor to endure flooding and scour. Such substrate buildup around the falls, along mid-river islands, and along the shores of the low-lying Riparian Woodlands immediately below the falls are often quite hospitable to the species.

A second native wildflower species in the genus Hibiscus is found in the Conewago Falls floodplain, this one in wetlands. The Swamp Rose Mallow (H. moscheutos) is similar to Halberd-leaved Rose Mallow, but sports more variable and colorful blooms. The leaves are toothed without the deep halberd-style lobes and, like the stems, are downy. As the common name implies, it requires swampy habitat with ample water and sunlight.

In summary, we find Partridge Pea in the Riverine Grasslands growing in sandy deposits left by flood and ice scour. We find Halberd-leaved Rose Mallow rooted at the border between shore and the emergent zone. We find Swamp Rose Mallow as an emergent in the wetlands of the floodplain. And finally, we find marshmallows in only one location in the area of Conewago Falls. Bon ap’.

SOURCES

Newcomb, Lawrence. 1977. Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide. Little, Brown and Company. Boston, Massachusetts.

Fussy Eaters

She ate only toaster pastries…that’s it…nothing else. Every now and then, on special occasions, when a big dinner was served, she’d have a small helping of mashed potatoes, no gravy, just plain, thank you. She received all her nutrition from several meals a week of macaroni and cheese assembled from processed ingredients found in a cardboard box. It contains eight essential vitamins and minerals, don’t you know? You remember her, don’t you?

Adult female butterflies must lay their eggs where the hatched larvae will promptly find the precise food needed to fuel their growth. These caterpillars are fussy eaters, with some able to feed upon only one particular species or genus of plant to grow through the five stages, the instars, of larval life. The energy for their fifth molt into a pupa, known as a chrysalis, and metamorphosis into an adult butterfly requires mass consumption of the required plant matter. Their life cycle causes most butterflies to be very habitat specific. These splendid insects may visit the urban or suburban garden as adults to feed on nectar plants, however, successful reproduction relies upon environs which include suitable, thriving, pesticide-free host plants for the caterpillars. Their survival depends upon more than the vegetation surrounding the typical lawn will provide.

The Monarch (Danaus plexippus), a butterfly familiar in North America for its conspicuous autumn migrations to forests in Mexico, uses the milkweeds (Asclepias) almost exclusively as a host plant. Here at Conewago Falls, wetlands with Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and unsprayed clearings with Common Milkweed (A. syriaca) are essential to the successful reproduction of the species. Human disturbance, including liberal use of herbicides, and invasive plant species can diminish the biomass of the Monarch’s favored nourishment, thus reducing significantly the abundance of the migratory late-season generation.

Butterflies are good indicators of the ecological health of a given environment. A diversity of butterfly species in a given area requires a wide array of mostly indigenous plants to provide food for reproduction. Let’s have a look at some of the species seen around Conewago Falls this week…

The spectacularly colorful butterflies are a real treat on a hot summer day. Their affinity for showy plants doubles the pleasure.

By the way, I’m certain by now you’ve recalled that fussy eater…and how beautiful she grew up to be.

SOURCES

Brock, Jim P., and Kaufman, Kenn. 2003. Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY.